Trends in Practical Heritage Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Og Miljøudvalget

Teknik- og Miljøudvalget Referat 6. december 2016 kl. 16:00 Udvalgsværelse 1 Indkaldelse Bodil Kornbek Mette Schmidt Olsen Henriette Breum Jakob Engel-Schmidt Henrik Brade Johansen Birgitte Hannibal Aase Steffensen Jakob Engel-Schmidt var fraværende i stedet deltog Søren P Rasmussen. Derudover deltog: Bjarne Holm Markussen Sidsel Poulsen Christian Røn Østeraas Mads Henrik Lindberg Chritiansen Thomas Hansen Katrine Lindegaard (referent) Indholdsfortegnelse Pkt. Tekst Side 1 3. anslået regnskab 2016 - Teknik- og Miljøudvalgets område (Beslutning) 3 2 Proces for udmøntning af budgetaftalen for 2017-2020 (Beslutning) 5 3 Brune turistoplysningstavler langs motorveje i kommunen (Beslutning) 7 4 Valg af skrifttype til vejnavneskilte (Beslutning) 11 5 Lyngby-Taarbæk Kommunes deltagelse i Loop City-samarbejdet (Beslutning) 15 6 Igangværende mobilitetsprojekter (Orientering) 17 7 Etablering af affaldsskakte ved nybyggeri (Beslutning) 19 8 Takster for vand og spildevand 2017 (Beslutning) 21 Trafikale skitseprojekter i forbindelse med byudvikling langs Helsingørmotorvejen 9 25 (Beslutning) Deltagelse i Vejdirektoratets udbud i 2017 af daglig vedligeholdelse af Lyngby 10 30 Omfartsvej (Beslutning) 11 Kommende sager 32 12 Lukket punkt, Miljøsag 33 13 Meddelelser 34 2 Punkt 1 3. anslået regnskab 2016 - Teknik- og Miljøudvalgets område (Beslutning) Resumé Teknik- og Miljøudvalget skal behandle forvaltningens redegørelse vedrørende 3. anslået regnskab for 2016 og indstille til Økonomiudvalget og Kommunalbestyrelsen. Forvaltningen foreslår, at udvalget: 1. drøfter redegørelsen om 3. anslået regnskab på udvalgets område 2. tager redegørelsen til efterretning. Sagsfremstilling 3. anslået regnskab er udarbejdet på baggrund af korrigeret budget 2016, forbruget pr. 30. september 2016 og skøn for resten af året. Økonomiudvalget drøftede 3. anslået regnskab d. 17. november 2016 og besluttede, at tage redegørelsen til efterretning og at oversende redegørelsen til fagudvalgene. -

Swiss: 1,600 Kilometres Long, It Spans Four 4 /XJDQR࣠±࣠=HUPDWW Linguistic Regions, Five Alpine Passes, P

mySwitzerland #INLOVEWITHSWITZERLAND GRAND TOUR The road trip through Switzerland Whether you’re travelling by car or by motorcycle – mountain pass roads like the Tremola are one of the highlights of the Grand Tour of Switzerland. Switzerland in 10 stages Marvel at the sunrise over the 1 =XULFK࣠±࣠$SSHQ]HOO Matterhorn at least once in your lifetime. p. 12 Don’t miss wandering through the vine- yards of the winemaking villages of the 2 $SSHQ]HOO࣠±࣠6W0RULW] Lavaux. Or conquering the cobblestoned p. 15 Tremola on the south side of the Gotthard Pass. The Grand Tour of Switzerland is a 3 6W0RULW]࣠±࣠/XJDQR magnificent holiday and driving experi- p. 20 ence – and a concentration of all things Swiss: 1,600 kilometres long, it spans four 4 /XJDQR࣠±࣠=HUPDWW linguistic regions, five Alpine passes, p. 24 12 UNESCO World Heritage Properties and 22 stunning lakes. MySwitzerland is happy 5 =HUPDWW࣠±࣠/DXVDQQH to present a selection of highlights from p. 30 10 fascinating stages. Have fun exploring! 6 *HQHYD±࣠1HXFKkWHO p. 32 7 Basel 7 ࣠±࣠1HXFKkWHO 1 2 p. 35 10 8 9 8 1HXFKkWHO࣠±࣠%HUQ p. 40 3 9 %HUQ࣠±࣠/XFHUQH 6 5 4 p. 42 10 /XFHUQH±࣠=XULFK You will find a map of the Grand Tour at the back of the magazine. For more information, p. 46 please see MySwitzerland.com/grandtour 3 Grand Tour: people and events JUST LIKE OLD FRIENDS The Grand Tour of Switzerland is a journey of sights and discoveries. You will meet many different people along the tour, and thus enjoy the most enriching of experiences. -

UNESCO World Heritage Properties in Switzerland February 2021

UNESCO World Heritage properties in Switzerland February 2021 www.whes.ch Welcome Dear journalists, Thank you for taking an interest in Switzerland’s World Heritage proper- ties. Indeed, these natural and cultural assets have plenty to offer: en- chanting cityscapes, unique landscapes, historic legacies and hidden treasures. Much of this heritage was left to us by our ancestors, but nature has also played its part in making the World Heritage properties an endless source of amazement. There are three natural and nine cultur- al assets in total – and as unique as each site is, they all have one thing in common: the universal value that we share with the global community. “World Heritage Experience Switzerland” (WHES) is the umbrella organisation for the tourist network of UNESCO World Heritage properties in Switzerland. We see ourselves as a driving force for a more profound and responsible form of tourism based on respect and appreciation. In this respect we aim to create added value: for visitors in the form of sustainable experiences and for the World Heritage properties in terms of their preservation and appreciation by future generations. The enclosed documentation will offer you the broadest possible insight into the diversity and unique- ness of UNESCO World Heritage. If you have any questions or suggestions, you can contact us at any time. Best regards Kaspar Schürch Managing Director WHES [email protected] Tel. +41 (0)31 544 31 17 More information: www.whes.ch Page 2 Table of contents World Heritage in Switzerland 4 Overview -

Natmus M65 Folder ENG.Indd.Ps, Page 2 @ Preflight

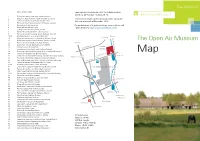

Free admission MUSEUM BUILDINGS Opening hours: From Easter until the Autumn holiday (week no. 42) Tuesday – Sunday 10-17. 1 Fisherman’s cottage from Agger, North Sea Coast 2 Skipper’s cottage from the island Fanø, North Sea Coast The museum is open for Christmas activities during the 3 Farmstead from the island Bornholm. Water mill first two weekends of December 10-16. 4 Farmstead from Ostenfeld, Southern Schleswig, Germany 5 Fuglevad wind mill, original site For guided tours in English and larger events, please call 6 Water mill from Ellested, Funen +45 33 47 38 57 or mail [email protected] 7 Gaming stone from Løve, Central Jutland 8 Farmstead from Karup Hearth, Central Jutland 9 Farmstead from the island Læsø in the Kattegat. Post mill 15-19 Buildings from the Faeroe islands. Water mill Nærum Helsingør 20 Milestone from the district of Holstebro, Western Jutland 21 Bridge from Smedevad near Holstebro, Western Jutland The Open Air Museum 22 Farmstead from Vemb, Western Justland. Forge Hillerød 25 Manor from Fjellerup, Djursland, Eastern Jutland 26 Summerhouse from Stege, Møn Brede Skodsborgvej 27 Summerhouse from Skovshoved, Northern Zealand Works 29 Fisherman’s huts from Nymindegab, Western Jutland. Dismantled Map 30 Farmstead from Lønnestak, Western Jutland 31 Farmstead from Eiderstedt (Hauberg), Southern Schleswig, Germany Brede St. Kongevejen 201 I.C. Modewegs s 32 Farmstead from Southern Sejerslev, Northern Schleswig Vej 33 Lace-making school from Northern Sejerlev, Northern Schleswig Bredevej 34 Farmstead from the island Rømø, North Sea Coast P 37-40 Buildings from the North-Eastern Schleswig 41 Shoemaker’s cottage from Ødis Bramrup, Eastern Jutland The Open Air Museum 42 Farmstead from True near Århus, Eastern Jutland 43 Potter’s workshop from Sorring, Eastern Jutland 44-45 Smallholder’s farmstead and barn from Als, Northern Schleswig 54 Farmstead from Halland, Sweden 55 Twin farmstead form Göinge, Scania, Sweden P Fuglevad St. -

Gotthard Panorama Express. Sales Manual 2021

Gotthard Panorama Express. Sales Manual 2021. sbb.ch/en/gotthard-panorama-express Enjoy history on the Gotthard Panorama Express to make travel into an experience. This is a unique combination of boat and train journeys on the route between Central Switzerland and Ticino. Der Gotthard Panorama Express: ì will operate from 1 May – 18 October 2021 every Tuesday to Sunday (including national public holidays) ì travels on the line from Lugano to Arth-Goldau in three hours. There are connections to the Mount Rigi Railways, the Voralpen-Express to Lucerne and St. Gallen and long-distance trains towards Lucerne/ Basel, Zurich or back to Ticino via the Gotthard Base Tunnel here. ì with the destination Arth-Goldau offers, varied opportunities; for example, the journey can be combined with an excursion via cog railway to the Rigi and by boat from Vitznau. ì runs as a 1st class panorama train with more capacity. There is now a total of 216 seats in four panorama coaches. The popular photography coach has been retained. ì requires a supplement of CHF 16 per person for the railway section. The supplement includes the compulsory seat reservation. ì now offers groups of ten people or more a group discount of 30% (adjustment of group rates across the whole of Switzerland). 2 3 Table of contents. Information on the route 4 Route highlights 4–5 Journey by boat 6 Journey on the panorama train 7 Timetable 8 Train composition 9 Fleet of ships 9 Prices and supplements 12 Purchase procedure 13 Services 14 Information for tour operators 15 Team 17 Treno Gottardo 18 Grand Train Tour of Switzerland 19 2 3 Information on the route. -

Gratis / Free Rabat / Discount

Ta d re M ø l l e 25/0 0 Teatermuseet i Hofteatret / The Theatre Museum at The Court Theatre 40/0 0 Thorvaldsens Museum 50/0 0 GRATIS / FREE Tivoli / Tivoli Gardens 100/100 0 COPENHAGENCARD Tycho Brahe Planetarium 144/94 0 Tøjhusmuseet / The Royal Arsenal Museum 0/0 0* Adults/ Copenhagen Vedbækfundene / Vedbæk Finds Museum 30/0 0 Museer og attraktioner / Museums & attractions Children Card Visit Carlsberg 90/60 0 Amalienborg 95/0 0 Vor Frelsers Kirke /Church of our Saviour 45/10 0 Amber Museum Copenhagen 25/10 0 Zoologisk Have / Copenhagen ZOO 170/95 0 Arbejdermuseet /The Workers Museum 65/0 0 Zoologisk Museum / Zoological Museum 140/75 0 ARKEN Museum for moderne kunst / Museum of Modern Art 110/0 0 Øresundsakvariet / Øresund Aquarium 79/59 0 Bakkehusmuseet /The Bakkehus Museum 50/0 0 Brede Værk (Nationalmuseet) /Brede Works 0/0 0* Tranport i Hovedstadsregionen Bådfarten / Boat Tours 70/50 0 / Transportation in the Capital Region. Canal Tours Copenhagen 80/40 0 Bus, tog, havnebus, Metro/ bus, train, harbour bus, Metro 0 Casino Copenhagen 95/- 0 Cirkusmuseet / Circus Museum 50/0 0 Cisternerne / The Cisterns 50/0 0 Danmarks Tekniske Museum / The Danish Museum of Science and Technology 70/0 0 Dansk Arkitektur Center / Danish Architecture Centre 60/0 0 RABAT / DISCOUNT Dansk Jagt- og Skovbrugsmuseum / Danish Museum for Hunting & Forestry 70/0 0 Dansk Jødisk Museum / The Danish Jewish Museum 50/0 0 De Kongelige Repræsentationslokaler / The Royal Reception Rooms 90/45 0 Adults/ Copenhagen De Kongelige Stalde / The Royal Stables 50/25 0 Museer -

Focalizzare Il Private Banking Graphic

Banca del Sempione Annual Report Report on our forty-sixth year of operations, presented to the Shareholders’Meeting of 23 April 2007 Looking Beyond. To reach major milestones takes skill, dedication, and the ability to imagine original solutions. Choosing Banca del Sempione means trusting a partner that knows how to deal in financial markets with professionalism, pragmatism, and creativity. Contents 6 Bank’s governing bodies 9 Chairman’s report 1. Consolidated annual financial statements of the group Banca del Sempione 18 Consolidated balance sheet 19 Consolidated income statement 20 Consolidated statement of Cash Flows 21 Notes to the annual consolidated financial statements 39 Auditor’s Report 2. Other activities 46 Accademia SGR SpA 48 Base Investments SICAV 51 Banca del Sempione (Overseas), Nassau 3. Annual financial statements of Banca del Sempione 58 Balance sheet 59 Income statement 63 Notes to the annual financial statements 69 Auditor’s Report The Value of Balance. When one lays down ambitious objectives, technical skill is not enough. One needs to evaluate the context with prudence, the options in the field, the resources available, and the time horizon. Your Bank knows it, because it values good sense. Banca del Sempione Bank’s governing bodies Board of Directors of Management of the Submanagement of the Banca del Sempione Banca del Sempione Banca del Sempione Avv. Fiorenzo Perucchi* chairman Stefano Rogna general manager Ermes Bizzozero assistant manager Dr. Günter Jehring* vice chairman Roberto Franchi assistant general manager (01.01.07) Mario Contini assistant manager Bruno Armao Massimo Gallacchi manager Sascha Kever assistant manager (01.01.07) Prof. -

“We Have to Move Forward!” the Slovak Minority in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1935–1939

“WE HAVE TO MOVE FORWARD!” THE SLOVAK MINORITY IN THE KINGDOM OF YUGOSLAVIA IN 1935–1939 VLATKA DUGAČKI – MILAN SOVILJ DUGAČKI, Vlatka – SOVILJ, Milan. “We Have to Move Forward!” The slovak minority in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1935–1939. Historický časopis, 2020, 68, 5, pp. 815–839, Bratislava. The paper “We Have to Move Forward!” focuses on presenting the or- ganisation and position of the Slovak minority in the Kingdom of Yugo- slavia, placing emphasis on the period between the elections for the Na- tional Assembly in 1935 and the establishment of the Banat of Croatia in 1939. Special attention was paid to the minority’s viewpoints on the Kingdom’s internal politics, as well as, externally, the conditions in the mother country, that is, Czechoslovakia and Slovakia after the first half of March 1939. The research required the use of archived materials from the Croatian State Archives in Zagreb and the Slovak National Archives in Bratislava, the Slovak minority newspapers, which, among other things, helped reconstruct the zeitgeist, and also the published sources and rele- vant literature. Although the Slovaks inhabited the entire territory of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, it is important to mention that the representative area used for this research was the Danube Banat (mostly the area of the present day Vojvodina and Baranja), which was most densely populated by the Slovak minority. Keywords: Slovak minority. Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Banat of Croatia. Czechoslovakia. Slovak Republic. Interwar period. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/histcaso.2020.68.5.3 Introduction In the interwar period, the Yugoslav state represented a very heterogeneous for- mation with regard to its political, social and national structure. -

Castelli Di Bellinzona

Trenino Artù -design.net Key Escape Room Torre Nera La Torre Nera di Castelgrande vi aspetta per vivere una entusiasmante espe- rienza e un fantastico viaggio nel tempo! Codici, indizi e oggetti misteriosi che vi daranno la libertà! Una Room ambientata in una location suggestiva, circondati da 700 anni di storia! Prenotate subito la vostra avventura medievale su www.blockati.ch Escape Room Torre Nera C Im Turm von Castelgrande auch “Torre Nera” genannt, kannst du ein aufre- gendes Erlebnis und eine unglaubliche Zeitreise erleben! Codes, Hinweise M und mysteriöse Objekte entschlüsseln, die dir die Freiheit geben! Ein Raum in Y einer anziehender Lage, umgeben von 700 Jahren Geschichte! CM Buchen Sie jetzt Ihr mittelalterliches Abenteuer auf www.blockati.ch MY Escape Room Tour Noire CY La Tour Noire de Castelgrande, vous attends pour vivre une expérience pas- CMY sionnante et un voyage fantastique dans le temps ! Des codes, des indices et des objets mystérieux vous donneront la liberté! Une salle dans un lieu Preise / Prix / Prices Orari / Fahrplan / Horaire / Timetable K évocateur, entouré de 700 ans d’histoire ! Piazza Collegiata Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure Réservez votre aventure médiévale dès maintenant sur www.blockati.ch Trenino Artù aprile-novembre Do – Ve / So – Fr / Di – Ve / Su – Fr 10.00 / 11.20 / 13.30 / 15.00 / 16.30 Adulti 12.– Piazza Governo Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure Escape Room Black Tower Sa 11.20 / 13.30 The Black Tower of Castelgrande, to live an exciting experience and a fan- Ridotti Piazza Collegiata Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure tastic journey through time! Codes, clues and mysterious objects that will Senior (+65), studenti e ragazzi 6 – 16 anni 10.– Sa 15.00 / 16.30 give you freedom! A Room set in an evocative location, surrounded by 700 a Castelgrande, years of history! Gruppi (min. -

Forskningsberetning 2002

NATIONALMUSEETS FORSKNING 2002 Nationalmuseet Juni 2003 Forord Forskningsberetning 2002 giver en oversigt over forskningsindsatsen på Nationalmuseets ti nuværende forskningsområder, det daværende Forskningssekretariats og Bibliotekstjenestens funktioner i relation til forskningen. I udformningen af beretningen er der taget hensyn til den rådgivning som Nationalmuseets Eksterne Forskningsudvalg (NEF) har givet i forbindelse med behandlingen af Forskningsberetning 2001. I lighed med Forskningsberetning 2001 er museets forskning opdelt og beskrevet ud fra de ti nuværende hovedforskningsområder og det organisatoriske tilhørsforhold af aktiviteterne på forskningsområderne træder dermed i baggrunden. I modsætning til Forskningsberetning 2001 er der ikke udarbejdet et særskilt Projektkatalog, idet projekterne med deres fulde beskrivelse er indarbejdet under de respektive forskningsområder ud fra den betragtning, at det dermed bliver muligt at få et overblik over de samlede aktiviteter i hvert ernkelt forskningsområde. Beretningen indeholder tre afsnit: I. Nationalmuseets forskning generelt, II. Glimt fra forskningsområderne udformet som en række mindre artikler og III. Forskningsområdernes aktiviteter, herunder basisaktiviteter, projekter og publikationer. Som bilag findes en samlet publikationsliste. Forskningsadministrationen Forsknings- og Formidlingsafdelingen 2 Indholdsfortegnelse NATIONALMUSEETS FORSKNING FORORD ....................................................................................................................p.2 INDHOLDSFORTEGNELSE -

The Network of UNESCO World Heritage Properties in Switzerland

Old City of Berne Prehistoric Pile Dwellings around the Alps Fountains, arcades and historic charm The network Official UNESCO World Heritage property since 1983, the Outstanding archaeological sites Old City of Berne rises majestically above a loop in the The serial of “Prehistoric Pile Dwellings around the Alps” River Aare. It bears witness to the ambitious scale of of UNESCO World comprises a selection of 111 sites in six countries (D, F, urban development in medieval Europe and delights visi- I, SLO, A, CH), 56 of which are situated in Switzerland. tors with its pleasant, relaxed charm. The cafés located in Thanks to their location partly or fully submerged in water, vaulted cellars are the perfect place to take a break and their remains are extremely well preserved: finds made Heritage properties the covered medieval arcades, stretching for kilometers, from stone, pottery and especially organic materials give are simply a shopper’s paradise. © SC ittes fascinating insight into life between 5,000 and 500 BC. © Bern Tourismus G UNESCO Palaf UNESCO World Heritage properties in Switzerland. in Switzerland www.bern.com Cultural Heritage since 1983 www.palafittes.org Cultural Heritage since 2011 “World Heritage Experience Benedictine Convent of Rhaetian Railway in the Switzerland” (WHES) is St John at Müstair Albula / Bernina Landscapes the umbrella organisation for the tourist network The nuns open their doors A triumph of railway engineering of UNESCO World Heritage th Founded as a monastery by Charlemagne in the 8 century The rail line across Albula and Bernina is a master stroke properties in Switzerland. and later converted into a convent, this complex exhibits of structural engineering and route planning. -

Communism and Nationalism in Postwar Cyprus, 1945-1955

Communism and Nationalism in Postwar Cyprus, 1945-1955 Politics and Ideologies Under British Rule Alexios Alecou Communism and Nationalism in Postwar Cyprus, 1945-1955 Alexios Alecou Communism and Nationalism in Postwar Cyprus, 1945-1955 Politics and Ideologies Under British Rule Alexios Alecou University of London London , UK ISBN 978-3-319-29208-3 ISBN 978-3-319-29209-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-29209-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016943796 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the pub- lisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.