Chemical Investigations of Element 108, Hassium (Hs)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

IUPAC/IUPAP Provisional Report)

Pure Appl. Chem. 2018; 90(11): 1773–1832 Provisional Report Sigurd Hofmanna,*, Sergey N. Dmitrieva, Claes Fahlanderb, Jacklyn M. Gatesb, James B. Robertoa and Hideyuki Sakaib On the discovery of new elements (IUPAC/IUPAP Provisional Report) Provisional Report of the 2017 Joint Working Group of IUPAC and IUPAP https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2018-0918 Received August 24, 2018; accepted September 24, 2018 Abstract: Almost thirty years ago the criteria that are currently used to verify claims for the discovery of a new element were set down by the comprehensive work of a Transfermium Working Group, TWG, jointly established by IUPAC and IUPAP. The recent completion of the naming of the 118 elements in the first seven periods of the Periodic Table of the Elements was considered as an opportunity for a review of these criteria in the light of the experimental and theoretical advances in the field. In late 2016 the Unions decided to estab- lish a new Joint Working Group, JWG, consisting of six members determined by the Unions. A first meeting of the JWG was in May 2017. One year later this report was finished. In a first part the works and conclusions of the TWG and the Joint Working Parties, JWP, deciding on the discovery of the now named elements are summarized. Possible experimental developments for production and identification of new elements beyond the presently known ones are estimated. Criteria and guidelines for establishing priority of discovery of these potential new elements are presented. Special emphasis is given to a description for the application of the criteria and the limits for their applicability. -

The Quest to Explore the Heaviest Elements Raises Questions About How Far Researchers Can Extend Mendeleev’S Creation

ON THE EDGE OF THE PERIODIC TABLE The quest to explore the heaviest elements raises questions about how far researchers can extend Mendeleev’s creation. BY PHILIP BALL 552 | NATURE | VOL 565 | 31 JANUARY 2019 ©2019 Spri nger Nature Li mited. All ri ghts reserved. ©2019 Spri nger Nature Li mited. All ri ghts reserved. FEATURE NEWS f you wanted to create the world’s next undiscovered element, num- Berkeley or at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, ber 119 in the periodic table, here’s a possible recipe. Take a few Russia — the group that Oganessian leads — it took place in an atmos- milligrams of berkelium, a rare radioactive metal that can be made phere of cold-war competition. In the 1980s, Germany joined the race; I only in specialized nuclear reactors. Bombard the sample with a beam an institute in Darmstadt now named the Helmholtz Center for Heavy of titanium ions, accelerated to around one-tenth the speed of light. Ion Research (GSI) made all the elements between 107 and 112. Keep this up for about a year, and be patient. Very patient. For every The competitive edge of earlier years has waned, says Christoph 10 quintillion (1018) titanium ions that slam into the berkelium target Düllmann, who heads the GSI’s superheavy-elements department: — roughly a year’s worth of beam time — the experiment will probably now, researchers frequently talk to each other and carry out some produce only one atom of element 119. experiments collaboratively. The credit for creating later elements On that rare occasion, a titanium and a berkelium nucleus will collide up to 118 has gone variously, and sometimes jointly, to teams from and merge, the speed of their impact overcoming their electrical repul- sion to create something never before seen on Earth, maybe even in the Universe. -

Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2015 Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants John Dustin Despotopulos University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Chemistry Commons Repository Citation Despotopulos, John Dustin, "Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants" (2015). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2345. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7645877 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVESTIGATION OF FLEROVIUM AND ELEMENT 115 HOMOLOGS WITH MACROCYCLIC EXTRACTANTS By John Dustin Despotopulos Bachelor of Science in Chemistry University of Oregon 2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy -

BNL-79513-2007-CP Standard Atomic Weights Tables 2007 Abridged To

BNL-79513-2007-CP Standard Atomic Weights Tables 2007 Abridged to Four and Five Significant Figures Norman E. Holden Energy Sciences & Technology Department National Nuclear Data Center Brookhaven National Laboratory P.O. Box 5000 Upton, NY 11973-5000 www.bnl.gov Prepared for the 44th IUPAC General Assembly, in Torino, Italy August 2007 Notice: This manuscript has been authored by employees of Brookhaven Science Associates, LLC under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886 with the U.S. Department of Energy. The publisher by accepting the manuscript for publication acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, world-wide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. This preprint is intended for publication in a journal or proceedings. Since changes may be made before publication, it may not be cited or reproduced without the author’s permission. DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or any third party’s use or the results of such use of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof or its contractors or subcontractors. -

Python Module Index 79

mendeleev Documentation Release 0.9.0 Lukasz Mentel Sep 04, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Getting started 3 1.1 Overview.................................................3 1.2 Contributing...............................................3 1.3 Citing...................................................3 1.4 Related projects.............................................4 1.5 Funding..................................................4 2 Installation 5 3 Tutorials 7 3.1 Quick start................................................7 3.2 Bulk data access............................................. 14 3.3 Electronic configuration......................................... 21 3.4 Ions.................................................... 23 3.5 Visualizing custom periodic tables.................................... 25 3.6 Advanced visulization tutorial...................................... 27 3.7 Jupyter notebooks............................................ 30 4 Data 31 4.1 Elements................................................. 31 4.2 Isotopes.................................................. 35 5 Electronegativities 37 5.1 Allen................................................... 37 5.2 Allred and Rochow............................................ 38 5.3 Cottrell and Sutton............................................ 38 5.4 Ghosh................................................... 38 5.5 Gordy................................................... 39 5.6 Li and Xue................................................ 39 5.7 Martynov and Batsanov........................................ -

The Elements.Pdf

A Periodic Table of the Elements at Los Alamos National Laboratory Los Alamos National Laboratory's Chemistry Division Presents Periodic Table of the Elements A Resource for Elementary, Middle School, and High School Students Click an element for more information: Group** Period 1 18 IA VIIIA 1A 8A 1 2 13 14 15 16 17 2 1 H IIA IIIA IVA VA VIAVIIA He 1.008 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 7A 4.003 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 Li Be B C N O F Ne 6.941 9.012 10.81 12.01 14.01 16.00 19.00 20.18 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 3 Na Mg IIIB IVB VB VIB VIIB ------- VIII IB IIB Al Si P S Cl Ar 22.99 24.31 3B 4B 5B 6B 7B ------- 1B 2B 26.98 28.09 30.97 32.07 35.45 39.95 ------- 8 ------- 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 4 K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr 39.10 40.08 44.96 47.88 50.94 52.00 54.94 55.85 58.47 58.69 63.55 65.39 69.72 72.59 74.92 78.96 79.90 83.80 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 5 Rb Sr Y Zr NbMo Tc Ru Rh PdAgCd In Sn Sb Te I Xe 85.47 87.62 88.91 91.22 92.91 95.94 (98) 101.1 102.9 106.4 107.9 112.4 114.8 118.7 121.8 127.6 126.9 131.3 55 56 57 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 6 Cs Ba La* Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt AuHg Tl Pb Bi Po At Rn 132.9 137.3 138.9 178.5 180.9 183.9 186.2 190.2 190.2 195.1 197.0 200.5 204.4 207.2 209.0 (210) (210) (222) 87 88 89 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 114 116 118 7 Fr Ra Ac~RfDb Sg Bh Hs Mt --- --- --- --- --- --- (223) (226) (227) (257) (260) (263) (262) (265) (266) () () () () () () http://pearl1.lanl.gov/periodic/ (1 of 3) [5/17/2001 4:06:20 PM] A Periodic Table of the Elements at Los Alamos National Laboratory 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 Lanthanide Series* Ce Pr NdPmSm Eu Gd TbDyHo Er TmYbLu 140.1 140.9 144.2 (147) 150.4 152.0 157.3 158.9 162.5 164.9 167.3 168.9 173.0 175.0 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 Actinide Series~ Th Pa U Np Pu AmCmBk Cf Es FmMdNo Lr 232.0 (231) (238) (237) (242) (243) (247) (247) (249) (254) (253) (256) (254) (257) ** Groups are noted by 3 notation conventions. -

Atomic Weights of the Elements 2011 (IUPAC Technical Report)*

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 85, No. 5, pp. 1047–1078, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1351/PAC-REP-13-03-02 © 2013 IUPAC, Publication date (Web): 29 April 2013 Atomic weights of the elements 2011 (IUPAC Technical Report)* Michael E. Wieser1,‡, Norman Holden2, Tyler B. Coplen3, John K. Böhlke3, Michael Berglund4, Willi A. Brand5, Paul De Bièvre6, Manfred Gröning7, Robert D. Loss8, Juris Meija9, Takafumi Hirata10, Thomas Prohaska11, Ronny Schoenberg12, Glenda O’Connor13, Thomas Walczyk14, Shige Yoneda15, and Xiang-Kun Zhu16 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada; 2Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY, USA; 3U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA, USA; 4Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements, Geel, Belgium; 5Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, Jena, Germany; 6Independent Consultant on MiC, Belgium; 7International Atomic Energy Agency, Seibersdorf, Austria; 8Department of Applied Physics, Curtin University of Technology, Perth, Australia; 9National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Canada; 10Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan; 11Department of Chemistry, University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria; 12Institute for Geosciences, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; 13New Brunswick Laboratory, Argonne, IL, USA; 14Department of Chemistry (Science) and Department of Biochemistry (Medicine), National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore; 15National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo, Japan; 16Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China Abstract: The biennial review of atomic-weight determinations and other cognate data has resulted in changes for the standard atomic weights of five elements. The atomic weight of bromine has changed from 79.904(1) to the interval [79.901, 79.907], germanium from 72.63(1) to 72.630(8), indium from 114.818(3) to 114.818(1), magnesium from 24.3050(6) to the interval [24.304, 24.307], and mercury from 200.59(2) to 200.592(3). -

Food Periodic Table

Food Chemistry Periodic Table Celebrating the International Year of the Periodic Table 2019 Created by Jane K Parker Acknowledgements and thanks to the RSC Food Group Committee: Robert Cordina, Bryan Hanley, Taichi Inuit, John Points, Kathy Ridgway, Martin Rose, Wendy Russell, Mike Saltmarsh, Maud Silvent, Clive Thomson, Kath Whittaker, Pete Wilde, and to Martin Chadwick, Cian Moloney and Ese Omoaruhke, for contributions to the elements, to Flaticons for use of their free icons, and to Alinea and TDMA for photographs of He and Ti. In slideshow mode, click on an element in periodic table to find out more, return via the RSC Food Group Logo. Contact: [email protected] Food Chemistry Periodic Table H He Li Be B C N O F Ne Na Mg Al Si P S Cl Ar K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr Rb Sr Y Zr Nb Mo Tc Ru Rh Pd Ag Cd In Sn Sb Te I Xe Cs Ba La Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt Au Hg Ti Pb Bi Po At Rn Fr Ra Ac Rf Db Sg Bh Hs Mt Ds Rg Cn Nh Fl Mc Lv Ts Og H Hydrogen 1 Occurrences in food Roles in food • Core element in organic compounds (fats, proteins, • H+ gives one of the five basic tastes – sour. carbohydrates, vitamins). • the higher the concentration of H+, the lower the pH • OH pH 2 Lemon juice (very sour) • H2 H2 H2 H2 H2 pH 3 Apple (sour) C C C C C C • pH 5 Meat (not sour) H3C C C C C C O H H H H H 2 2 2 2 2 • pH 7 Tea or water (not sour) • Hydrogen-bonds, one of the strongest forms of bonding, are crucial for the 3D-structure of many • Key element in water, H2O, which is 70% of the human body and 70% of many foods. -

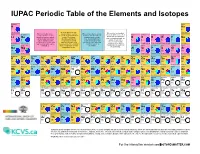

IUPAC Periodic Table of the Elements and Isotopes

IUPAC Periodic Table of the Elements and Isotopes hydrogen helium H He 1 2 1.008 Element has two or more [1.007 84, 1.008 11] Element has no standard 4.002 602(2) Element has two or more isotopes that are used to Element has only one isotope lithium beryllium atomic weight because all of boron carbon nitrogen oxygen fluorine neon isotopes that are used to determine its standard atomic that is used to determine its its isotopes are radioactive determine its atomic weight. weight. The isotopic standard atomic weight. Li Be and, in normal materials, no B C N O F Ne Variations are well known, abundance and atomic Thus, the standard atomic isotope occurs with a 3 4 and the standard atomic weights vary in normal weight is invariant and is 5 6 7 8 9 10 6.94 characteristic isotopic 10.81 12.011 14.007 15.999 weight is given as lower and materials, but upper and given as a single value with [6.938, 6.997] 9.012 1831(5) abundance from which a [10.806, 10.821] [12.0096, 12.0116] [14.006 43, 14.007 28] [15.999 03, 15.999 77] 18.998 403 163(6) 20.1797(6) upper bounds within square lower bounds of the standard an IUPAC evaluated standard atomic weight can sodium magnesium brackets, [ ]. atomic weight have not been uncertainty. aluminium silicon phosphorus sulfur chlorine argon be determined. Na Mg assigned by IUPAC. Al Si P S Cl Ar 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 24.305 28.085 32.06 35.45 39.95 22.989 769 28(2) [24.304, 24.307] 26.981 5385(7) [28.084, 28.086] 30.973 761 998(5) [32.059, 32.076] [35.446, 35.457] [39.792, 39.963] potassium calcium scandium titanium -

A Periodic Table of the Elements at Los Alamos National Laboratory Los Alamos National Laboratory's Chemistry Division Presents Periodic Table of the Elements

A Periodic Table of the Elements at Los Alamos National Laboratory Los Alamos National Laboratory's Chemistry Division Presents Periodic Table of the Elements A Resource for Elementary, Middle School, and High School Students Click an element for more information: Group** Period 1 18 IA VIIIA 1A 8A 1 2 13 14 15 16 17 2 1 H IIA IIIA IVA VA VIAVIIA He 1.008 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 7A 4.003 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 Li Be B C N O F Ne 6.941 9.012 10.81 12.01 14.01 16.00 19.00 20.18 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 3 Na Mg IIIB IVB VB VIB VIIB ------- VIII IB IIB Al Si P S Cl Ar 22.99 24.31 3B 4B 5B 6B 7B ------- 1B 2B 26.98 28.09 30.97 32.07 35.45 39.95 ------- 8 ------- 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 4 K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr 39.10 40.08 44.96 47.88 50.94 52.00 54.94 55.85 58.47 58.69 63.55 65.39 69.72 72.59 74.92 78.96 79.90 83.80 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 5 Rb Sr Y Zr NbMo Tc Ru Rh PdAgCd In Sn Sb Te I Xe 85.47 87.62 88.91 91.22 92.91 95.94 (98) 101.1 102.9 106.4 107.9 112.4 114.8 118.7 121.8 127.6 126.9 131.3 55 56 57 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 6 Cs Ba La* Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt AuHg Tl Pb Bi Po At Rn 132.9 137.3 138.9 178.5 180.9 183.9 186.2 190.2 190.2 195.1 197.0 200.5 204.4 207.2 209.0 (210) (210) (222) 87 88 89 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 114 116 118 7 Fr Ra Ac~RfDb Sg Bh Hs Mt --- --- --- --- --- --- (223) (226) (227) (257) (260) (263) (262) (265) (266) () () () () () () http://pearl1.lanl.gov/periodic/ (1 of 2) [5/10/2001 3:08:31 PM] A Periodic Table of the Elements at Los Alamos National Laboratory 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 Lanthanide Series* Ce Pr NdPmSm Eu Gd TbDyHo Er TmYbLu 140.1 140.9 144.2 (147) 150.4 152.0 157.3 158.9 162.5 164.9 167.3 168.9 173.0 175.0 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 Actinide Series~ Th Pa U Np Pu AmCmBk Cf Es FmMdNo Lr 232.0 (231) (238) (237) (242) (243) (247) (247) (249) (254) (253) (256) (254) (257) ** Groups are noted by 3 notation conventions. -

The Heaviest Elements in the Universe Cody Folden January 31, 2009 Theytheythey Keepkeepkeep Findingfindingfinding Newnewnew Elements.Elements.Elements

The Heaviest Elements in the Universe Cody Folden January 31, 2009 TheyTheyThey keepkeepkeep findingfindingfinding newnewnew elements.elements.elements. WhereWhereWhere areareare they?they?they? y Ytterby, Sweden is the namesake of four elements: ytterbium, yttrium, erbium, and terbium. TheTheThe Elements:Elements:Elements: 200920092009 y There are 91 naturally occurring elements (but it depends on how you count them). y The heaviest element that occurs in large quantity is uranium (atomic number 92). You can mine it like gold. y Technetium (atomic number 43) does not occur naturally. y Promethium (atomic number 61) does not occur naturally. y Plutonium-244 (244Pu) has been discovered in nature! (This isotope has a half-life of “only” 80 million years). y The artificial elements bring the total to 117. 244244244PuPuPu ininin NatureNatureNature (1971)(1971)(1971) y Sample: 1.0 × 10-18 g 244Pu per gram of sample. y Crust: 5 × 10-25 g 244Pu per gram of Earth. y There is an extremely weak “rain” of 244Pu that falls on the Earth, creating an equilibrium that balances its radioactive decay. TheTheThe PeriodicPeriodicPeriodic TableTableTable 200920092009 The heaviest elements are all produced artificially! WhatWhatWhat areareare allallall thesethesethese newnewnew elementselementselements goodgoodgood for?for?for? y The search for the heaviest elements answers questions like: y What is the heaviest element that can be formed? y What mechanism is involved in their production? y Does the periodicity of the elements continue for very high atomic numbers? y What are their chemical properties? y We also train future nuclear scientists. HowHowHow areareare newnewnew elementselementselements created?created?created? y We build up heavy elements by fusing two lighter elements together.