Life-History Responses of a Mayfly to Seasonal Constraints and Predation Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life History, Nymphal Growth Rates, and Feeding Habits of Siphlonisca Aerodromia Needham (Epherneroptera: Siphlonuridae) in ~Aine'

The life history, nymphal growth rates, and feeding habits of Siphlonisca aerodromia Needham (Epherneroptera: Siphlonuridae) in ~aine' K. ELIZABETHGIBBS AND TERRYM. MINGO Department of Entomology, University of Maine, Orono, ME, U. S. A. 04469 Received March 25. 1985 GIBBS,K. E., and T. M. MINGO.1986. The life history, nymphal growth rates, and feeding habits of Siphlonisca aerodromia Needham (Epherneroptera: Siphlonuridae) in Maine. Can. J. Zool. 64: 427-430. Siphlonisca aerodromia Needham has a univoltine life history in Maine. Adults emerge in late May or early June. Each female contains about 394 large (0.46 mm long) eggs covered with coiled fibers that anchor the eggs to the substrate. Eggs are deposited in the main channel of the stream and small nymphs appear in January. Nymphal growth rate (GHW)was expressed as a percent per day increase in head width. Initially nymphs feed on detritus and grow slowly (GHW= 0.28-0.79) at water temperatures near 0°C. Following snow melt, the nymphs move into the adjacent Carex floodplain. Here, water temperature increases, animal material, in the form of mayfly nymphs, becomes increasingly common in the diet, and growth rate increases (GHW = 2.13-2.89). The sex ratio of nymphs collected in May and June was 1: 1.8 (ma1e:female). GIBBS,K. E., et T. M. MINGO. 1986. The life history, nymphal growth rates, and feeding habits of Siphlonisca aerodromia Needham (Epherneroptera: Siphlonuridae) in Maine. Can. J. Zool. 64: 427-430. Dans le Maine, le cycle de Siphlonisca aerodromia Needham est univoltin. L'emergence des adultes se produit a la fin de mai ou au debut de juin. -

TB142: Mayflies of Maine: an Annotated Faunal List

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Technical Bulletins Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station 4-1-1991 TB142: Mayflies of aine:M An Annotated Faunal List Steven K. Burian K. Elizabeth Gibbs Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/aes_techbulletin Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Burian, S.K., and K.E. Gibbs. 1991. Mayflies of Maine: An annotated faunal list. Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 142. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Bulletins by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 0734-9556 Mayflies of Maine: An Annotated Faunal List Steven K. Burian and K. Elizabeth Gibbs Technical Bulletin 142 April 1991 MAINE AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION Mayflies of Maine: An Annotated Faunal List Steven K. Burian Assistant Professor Department of Biology, Southern Connecticut State University New Haven, CT 06515 and K. Elizabeth Gibbs Associate Professor Department of Entomology University of Maine Orono, Maine 04469 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Financial support for this project was provided by the State of Maine Departments of Environmental Protection, and Inland Fisheries and Wildlife; a University of Maine New England, Atlantic Provinces, and Quebec Fellow ship to S. K. Burian; and the Maine Agricultural Experiment Station. Dr. William L. Peters and Jan Peters, Florida A & M University, pro vided support and advice throughout the project and we especially appreci ated the opportunity for S.K. Burian to work in their laboratory and stay in their home in Tallahassee, Florida. -

Aquatic Insect Ecophysiological Traits Reveal Phylogenetically Based Differences in Dissolved Cadmium Susceptibility

Aquatic insect ecophysiological traits reveal phylogenetically based differences in dissolved cadmium susceptibility David B. Buchwalter*†, Daniel J. Cain‡, Caitrin A. Martin*, Lingtian Xie*, Samuel N. Luoma‡, and Theodore Garland, Jr.§ *Department of Environmental and Molecular Toxicology, Campus Box 7633, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27604; ‡Water Resources Division, U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Road, MS 465, Menlo Park, CA 94025; and §Department of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521 Edited by George N. Somero, Stanford University, Pacific Grove, CA, and approved April 28, 2008 (received for review February 20, 2008) We used a phylogenetically based comparative approach to evaluate ecosystems today (e.g., trace metals) (6). This variation in the potential for physiological studies to reveal patterns of diversity susceptibility has practical implications, because the ecological in traits related to susceptibility to an environmental stressor, the structure of aquatic insect communities is often used to indicate trace metal cadmium (Cd). Physiological traits related to Cd bioaccu- the ecological conditions in freshwater systems (7–9). Differ- mulation, compartmentalization, and ultimately susceptibility were ences among species’ responses to environmental stressors can measured in 21 aquatic insect species representing the orders be profound, but it is uncertain whether the cause is related to Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera. We mapped these ex- functional ecology [usually the assumption (10, 11)] or physio- perimentally derived physiological traits onto a phylogeny and quan- logical traits (5, 12–14), which have received considerably less tified the tendency for related species to be similar (phylogenetic attention. To the degree that either is involved, their link to signal). -

Abstract Poteat, Monica Deshay

ABSTRACT POTEAT, MONICA DESHAY. Comparative Trace Metal Physiology in Aquatic Insects. (Under the direction of Dr. David B. Buchwalter). Despite their dominance in freshwater systems and use in biomonitoring and bioassessment programs worldwide, little is known about the ion/metal physiology of aquatic insects. Even less is known about the variability of trace metal physiologies across aquatic insect species. Here, we measured dissolved metal bioaccumulation dynamics using radiotracers in order to 1) gain an understanding of the uptake and interactions of Ca, Cd and Zn at the apical surface of aquatic insects and 2) comparatively analyze metal bioaccumulation dynamics in closely-related aquatic insect species. Dissolved metal uptake and efflux rate constants were calculated for 19 species. We utilized species from families Hydropsychidae (order Trichoptera) and Ephemerellidae (order Ephemeroptera) because they are particularly species-rich and because they are differentially sensitive to metals in the field – Hydropsychidae are relatively tolerant and Ephemerellidae are relatively sensitive. In uptake experiments with Hydropsyche sparna (Hydropsychidae), we found evidence of two shared transport systems for Cd and Zn – a low capacity-high affinity transporter below 0.8 µM, and a second high capacity-low affinity transporter operating at higher concentrations. Cd outcompeted Zn at concentrations above 0.6 µM, suggesting a higher affinity of Cd for a shared transporter at those concentrations. While Cd and Zn uptake strongly co-varied across 12 species (r = 0.96, p < 0.0001), neither Cd nor Zn uptake significantly co-varied with Ca uptake in these species. Further, Ca only modestly inhibited Cd and Zn uptake, while neither Cd nor Zn inhibited Ca uptake at concentrations up to concentrations of 89 nM Cd and 1.53 µM Zn. -

Integrating Mesocosm Experiments and Field Data to Support Development of Water Quality Criteria

Integrating mesocosm experiments and field data to support development of water quality criteria Will Clements Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO Field High assessments Mesocosm experiments Laboratory toxicity tests Low Spatiotemporal RealismScale & Low High Control & Replication Criticism of Small-Scale Experiments in Ecological Research “Microcosm experiments have limited relevance in community and ecosystem ecology” “Irresponsible for academic ecologists to produce larval microcosmologists” • Provide fast results: good for career development • Keep faculty on campus under the watchful eye of administrators Carpenter, 1996 Overview • Differences between field & lab responses to contaminants • A few hypotheses to explain these differences • Application of mesocosm experiments to test these hypotheses and to support the development of water quality criteria Spatially extensive and long-term surveys of metal-contaminated streams in Colorado EPA EMAP (n = 95) USGS & CSU (n = 154) S. Platte River Green R. Denver Colorado Springs Arkansas River Rio Grande Test Reference Probability Mineral Belt Quantify relationship among metals, aquatic insect communities and other environmental variables Sensitivity of aquatic insects (especially mayflies) Highly significant effects on mayflies at relatively low metal concentrations 160 140 Total mayfly abundance 120 100 F=14.01 s.e.) + p<0.0001 80 60 Mean ( Mean 40 20 0 < 1 CCU1-2 CCU2-10 CCU> 10 CCU Metal Category Clements et al. 2000 Schmidt, Clements & Cade, 2012 But, lab toxicity data do not reflect this sensitivity Copper Zinc Species LC50 Species LC50 Ephemerella subvaria 320 µg/L Ephemerella sp. > 68.8 mg/L Drunella grandis 201 µg/L Cinygmula sp 68.6 mg/L Stenonema sp. 453 µg/L Drunella doddsi > 64.0 mg/L Drunella grandis 190 µg/L Rhithrogena hageni 50.5 mg/L Rhithrogena hageni 137 µg/L Baetis tricaudatus 11.6 mg/L Isonychia bicolor 223 µg/L Baetis tricaudatus > 2.9 mg/L Warnick and Bell 1969; Goettl et al. -

Spring2005.Pdf

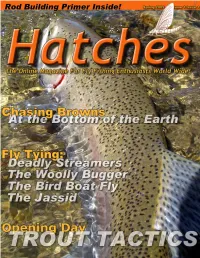

Feature Pattern President & Publisher Will Mullis Chasing Browns at the Bottom of the Earth by Graham Owen Managing Editor Nick Pujic Deadly Streamers: Hales’ Minnow by Nick Pujic Editor David Fix Entomology Focus: The Hendrickson Hatch Layout & Design by Roger Rohrbeck Nick Pujic Karin Zandbergen Opening Day Trout Tactics by Steve Clark Contributing Editors Robert “Bob” Farrand Steve Clark Mullis’ Bird Boat Chris “Carl” Carlin by Will Mullis Roger Rohrbeck Graham Owen Rod Building Primer - Part 1 Rich Soriano by Chris Carlin David Fix Contributing Photographers The Jassid Jason Neuswanger by David Fix Glen Hales Ralf Maky Hatches Magazine is a joint venture by: www.FlyTyingForum.com Editorial & Editor’s Feature Pattern & By Nick Pujic www.OnlineFlyTyer.com Saltwater Fly Fishing Q & A On the Cover: by Rich Soriano Fresh Great Lakes Spring steelhead. Joe’s Sculpin Photo Credit: Karin Zandbergen FTF Member Gallery Hook: Alec jackson Spey #5 By FTF members Eyes: Lead dumbell eyes paineted yellow & black Hatches Magazine is made available free of Tail: 6 to 8 strands of matching colored Krystal Flash charge to all readers due to the unrelenting desire Wing: Matching colored zonker strip to expand the sport of fly fishing, and the art of fly Beginner’s Bench - Tools & Woolly Buggers tying, on behalf of all parties listed above. by Robert Farrand Body: Super Fly Tri-Lobal hackle in matching colors Front Fins: Barred chickabou, 2 plumes per side Hatches Magazine thanks these volunteers for Head: Hareline woolhead dubbing, matching color their time and efforts required to make this Fly Fishing & Tying Product Reviews Field Editors publication possible. -

Tomah Mayfly Assessment

TOMAH MAYFLY ASSESSMENT February 21, 2001 Dr. K. Elizabeth Gibbs Marcia Siebenmann Dr. Mark McCollough Andrew Weik Beth Swartz MAINE DEPARTMENT OF INLAND FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE WILDLIFE DIVISION RESOURCE ASSESSMENT SECTION ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES PROGRAM Tomah Mayfly Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUC TION............................................................................................. 4 NATURAL HISTORY....................................................................................... 5 Description............................................................................................ 5 Distribution............................................................................................ 5 Life History.......................................................................................... 10 MANAGEMENT ............................................................................................ 16 Regulatory Authority ........................................................................... 16 Protection of Maine’s Invertebrates............................................... 16 Protection of Endangered and Threatened Invertebrates ............. 17 Habitat Protection.......................................................................... 19 Section 404 Clean Water Act ........................................... 20 The Maine Endangered Species Act ................................ 21 Natural Resource Protection Act of 1988 ......................... 22 Mandatory Shoreland Zoning .......................................... -

INFLUENCE of TEMPERATURE on GROWTH and TIMING of EMERGENCE of FOUR MAYFLY SPECIES by Corrine Anne Higley a THESIS Submitted to M

INFLUENCE OF TEMPERATURE ON GROWTH AND TIMING OF EMERGENCE OF FOUR MAYFLY SPECIES By Corrine Anne Higley A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Fisheries and Wildlife 2012 ABSTRACT TEMPERATURE INFLUENCE ON MAYFLY GROWTH AND EMERGENCE ON THE AU SABLE RIVER By Corrine A. Higley Individual growth rates and timing of emergence of four species of Ephemerellid mayflies were examined in relation to temperature among six sites on the Au Sable River near Grayling, Michigan. All species showed definite reductions in specific growth rates at lower temperatures, but incremental growth in mean length was continuous until emergence. These results indicate the degree-day concept is a useful tool in relating insect growth to thermal regime at intermediate temperatures, but is less accurate at temperatures approaching upper and lower development thresholds. Mean larval size and growth rates varied unpredictably among taxa and across sites, and could not be explained by variations in temperature at different sites. Other habitat variables not estimated in this study clearly influenced patterns in growth and timing of emergence of these species. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The efforts and support of many people helped make this study possible. Funding for this research was provided by the Graduate School, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife at Michigan State University, the George L. Disborough Fellowship, and Schrem’s West Michigan Trout Unlimited. I am also appreciative for the support and experience provided by the Janice Lee Fenske Excellence in Fisheries Management Fellowship. I would like to thank the members of my graduate committee, Dr. -

The Effects of Extended Photoperiods on the Drift of the Mayfly Ephemerella Subvaria Mcdunnough (Ephemeroptera : Ephemerellidae)

Hydrobiologia vol . 62, 3, pag . 209-214, 1979 THE EFFECTS OF EXTENDED PHOTOPERIODS ON THE DRIFT OF THE MAYFLY EPHEMERELLA SUBVARIA MCDUNNOUGH (EPHEMEROPTERA : EPHEMERELLIDAE) Jan J . H . CIBOROWSKI* Department of Zoology, Erindale College, University of Toronto, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada . L5L iC6 * Present address : Department of Zoology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada . T6G 2E9 Received March 20, 1978 Keywords : Drift, photoperiod, Ephemeroptera, development . Abstract of the organism . MUller (1965) showed that the nocturnal drift pattern of Baetis rhodani was directly related to the Field drift studies indicated that the nocturnal drift density of E . length of the dark period, however the effect of daylength subvaria nymphs was greater in early May than in early Novem- on subsequent nocturnal drift has not been elaborated . ber . This study examines the effect of extended photoperiods Laboratory studies showed that the number of individuals ap- pearing in the drift was a linear function of the duration of the on the drift of the mayfly Ephemerella subvaria Mc- preceding photoperiod . Nymphs had a greater propensity to Dunnough. drift when they were not in a state of active growth than when they were growing . The tendency of individuals in a single laboratory population to drift was observed to change under conditions of constant temperature and randomized photoperiod . This sug- Methods and materials gests that the shift was due to some internal physiological change rather than to an external cue . Ephemerella subvaria nymphs were collected for both life It is suggested that drift in E. subvaria functions as a method history analyses and experimental purposes from a riffle of relocation from fast-water areas to slow-water pools and stream margins . -

Insect Epigenetic Mechanisms Facing Anthropogenic-Derived Contamination, an Overview

insects Review Insect Epigenetic Mechanisms Facing Anthropogenic-Derived Contamination, an Overview Gabriela Olivares-Castro 1,*, Lizethly Cáceres-Jensen 2 , Carlos Guerrero-Bosagna 3,4 and Cristian Villagra 1 1 Instituto de Entomología, Universidad Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación, Avenida José Pedro Alessandri 774, Santiago 7760197, Chile; [email protected] 2 Laboratorio de Físicoquímica Analítica, Departamento de Química, Facultad de Ciencias Básicas, Universidad Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación, Santiago 7760197, Chile; [email protected] 3 Department of Physics, Chemistry and Biology (IFM), Linköping University, 581 83 Linköping, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Environmental Toxicology Program, Department of Integrative Biology, Uppsala University, 752 36 Uppsala, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Epigenetic molecular mechanisms (EMMs) are capable of regulating and stabiliz- ing a wide range of living cell processes without altering its DNA sequence. EMMs can be triggered by environmental inputs. In insects, EMMs contribute to explaining both negative effects as well as adaptive responses towards environmental cues. Among these stimuli are chemical stressors, such as pesticides. We review the link between EMMs and pesticides in insects. We suggest that pesticide chemical behavior promotes both lethal and sublethal exposure of both target and non-target insects. As a consequence, for several native and beneficial insect (e.g., pollinators), EMMs are involved in diseases and disruptive responses due to pesticides, while in the case of pest species, EMMs are Citation: Olivares-Castro, G.; linked in the development of pesticide resistance and hormesis. We discuss the consequences of these Cáceres-Jensen, L.; Guerrero-Bosagna, in the context of insect global decline and biotic homogenization. -

Invertebrates

Pennsylvania’s Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Invertebrates Version 1.1 Prepared by John E. Rawlins Carnegie Museum of Natural History Section of Invertebrate Zoology January 12, 2007 Cover photographs (top to bottom): Speyeria cybele, great spangled fritillary (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) (Rank: S5G5) Alaus oculatus., eyed elater (Coleoptera: Elateridae)(Rank: S5G5) Calosoma scrutator, fiery caterpillar hunter (Coleoptera: Carabidae) (Rank: S5G5) Brachionycha borealis, boreal sprawler moth (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), last instar larva (Rank: SHG4) Metarranthis sp. near duaria, early metarranthis moth (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) (Rank: S3G4) Psaphida thaxteriana (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) (Rank: S4G4) Pennsylvania’s Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Invertebrates Version 1.1 Prepared by John E. Rawlins Carnegie Museum of Natural History Section of Invertebrate Zoology January 12, 2007 This report was filed with the Pennsylvania Game Commission on October 31, 2006 as a product of a State Wildlife Grant (SWG) entitled: Rawlins, J.E. 2004-2006. Pennsylvania Invertebrates of Special Concern: Viability, Status, and Recommendations for a Statewide Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Plan in Pennsylvania. In collaboration with the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (C.W. Bier) and The Nature Conservancy (A. Davis). A Proposal to the State Wildlife Grants Program, Pennsylvania Game Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Text portions of this report are an adaptation of an appendix to a statewide conservation strategy prepared as part of federal requirements for the Pennsylvania State Wildlife Grants Program, specifically: Rawlins, J.E. 2005. Pennsylvania Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS)-Priority Invertebrates. Appendix 5 (iii + 227 pp) in Williams, L., et al. (eds.). Pennsylvania Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy. Pennsylvania Game Commission and Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Version 1.0 (October 1, 2005). -

Guidelines for Deriving Numerical National Water Quality Criteria for the Protection of Aquatic Organisms and Their Uses by Charles E

PB85-227049 Guidelines for Deriving Numerical National Water Quality Criteria for the Protection Of Aquatic Organisms and Their Uses by Charles E. Stephen, Donald I. Mount, David J. Hansen, John R. Gentile, Gary A. Chapman, and William A. Brungs Office of Research and Development Environmental Research Laboratories Duluth, Minnesota Narragansett, Rhode Island Corvallis, Oregon Notices This document has been reviewed in accordance with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency policy and approved for publication. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This document is available the public to through the National Technical Information Service (NTIS), 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161. Special Note This December 2010 electronic version of the 1985 Guidelines serves to meet the requirements of Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act. While converting the 1985 Guidelines to a 508-compliant version, EPA updated the taxonomic nomenclature in the tables of Appendix 1 to reflect changes that occurred since the table were originally produced in 1985. The numbers included for Phylum, Class and Family represent those currently in use from the Integrated Taxonomic Information System, or ITIS, and reflect what is referred to in ITIS as Taxonomic Serial Numbers. ITIS replaced the National Oceanographic Data Center (NODC) taxonomic coding system which was used to create the original taxonomic tables included in the 1985 Guidelines document (NODC, Third Addition - see Introduction). For more information on the NODC taxonomic codes, see http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/General/CDR-detdesc/taxonomic-v8.html. The code numbers included in the reference column of the tables have not been updated from the 1985 version.