Physics Genius Showed Oak Ridge How to Be Safe (As Published in the Oak Ridger’S Historically Speaking Column on November 3, 2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman Louis de Broglie Norman Ramsey Willis Lamb Otto Stern Werner Heisenberg Walther Gerlach Ernest Rutherford Satyendranath Bose Max Born Erwin Schrödinger Eugene Wigner Arnold Sommerfeld Julian Schwinger David Bohm Enrico Fermi Albert Einstein Where discovery meets practice Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology IQ ST in Baden-Württemberg . Introduction “But I do not wish to be forced into abandoning strict These two quotes by Albert Einstein not only express his well more securely, develop new types of computer or construct highly causality without having defended it quite differently known aversion to quantum theory, they also come from two quite accurate measuring equipment. than I have so far. The idea that an electron exposed to a different periods of his life. The first is from a letter dated 19 April Thus quantum theory extends beyond the field of physics into other 1924 to Max Born regarding the latter’s statistical interpretation of areas, e.g. mathematics, engineering, chemistry, and even biology. beam freely chooses the moment and direction in which quantum mechanics. The second is from Einstein’s last lecture as Let us look at a few examples which illustrate this. The field of crypt it wants to move is unbearable to me. If that is the case, part of a series of classes by the American physicist John Archibald ography uses number theory, which constitutes a subdiscipline of then I would rather be a cobbler or a casino employee Wheeler in 1954 at Princeton. pure mathematics. Producing a quantum computer with new types than a physicist.” The realization that, in the quantum world, objects only exist when of gates on the basis of the superposition principle from quantum they are measured – and this is what is behind the moon/mouse mechanics requires the involvement of engineering. -

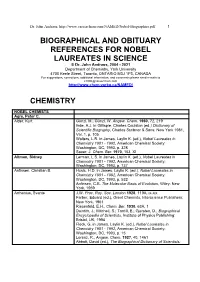

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Richard P. Feynman Author

Title: The Making of a Genius: Richard P. Feynman Author: Christian Forstner Ernst-Haeckel-Haus Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Berggasse 7 D-07743 Jena Germany Fax: +49 3641 949 502 Email: [email protected] Abstract: In 1965 the Nobel Foundation honored Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, Julian Schwinger, and Richard Feynman for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics and the consequences for the physics of elementary particles. In contrast to both of his colleagues only Richard Feynman appeared as a genius before the public. In his autobiographies he managed to connect his behavior, which contradicted several social and scientific norms, with the American myth of the “practical man”. This connection led to the image of a common American with extraordinary scientific abilities and contributed extensively to enhance the image of Feynman as genius in the public opinion. Is this image resulting from Feynman’s autobiographies in accordance with historical facts? This question is the starting point for a deeper historical analysis that tries to put Feynman and his actions back into historical context. The image of a “genius” appears then as a construct resulting from the public reception of brilliant scientific research. Introduction Richard Feynman is “half genius and half buffoon”, his colleague Freeman Dyson wrote in a letter to his parents in 1947 shortly after having met Feynman for the first time.1 It was precisely this combination of outstanding scientist of great talent and seeming clown that was conducive to allowing Feynman to appear as a genius amongst the American public. Between Feynman’s image as a genius, which was created significantly through the representation of Feynman in his autobiographical writings, and the historical perspective on his earlier career as a young aspiring physicist, a discrepancy exists that has not been observed in prior biographical literature. -

More Eugene Wigner Stories; Response to a Feynman Claim (As Published in the Oak Ridger’S Historically Speaking Column on August 29, 2016)

More Eugene Wigner stories; Response to a Feynman claim (As published in The Oak Ridger’s Historically Speaking column on August 29, 2016) Carolyn Krause has collected a couple more stories about Eugene Wigner, plus a response by Y- 12 to allegations by Richard Feynman in a book that included a story on his experience at Y-12 during World War II. … Mary Ann Davidson, widow of Jack Davidson, a longtime member of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Instrumentation and Controls Division, told me about Jack’s encounter with Wigner one day. Once Eugene Wigner had trouble opening his briefcase while visiting ORNL. He was referred to Jack Davidson in the old Instrumentation and Controls Division. Jack managed to open it for him. As was his custom, Wigner asked Jack about his research. Jack, who later won an R&D-100 award, said he was building a camera that will imitate a fly’s eye; in other words, it will capture light coming from a variety of directions. The topic of television and TV cameras came up. Wigner said he wondered how TV works. So Davidson explained the concept to him. Charles Jones told me this story about Eugene Wigner when he visited ORNL in the 1980s. Jones, who was technical director of the Holifield Heavy Ion Research Facility, said he invited Wigner to accompany him to the top of the HHIRF tower, and Wigner happily accepted the offer. At the top Wigner looked down at all the ORNL buildings, most of which had been constructed after he was the lab’s research director in 1946-47. -

Works of Love

reader.ad section 9/21/05 12:38 PM Page 2 AMAZING LIGHT: Visions for Discovery AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM IN HONOR OF THE 90TH BIRTHDAY YEAR OF CHARLES TOWNES October 6-8, 2005 — University of California, Berkeley Amazing Light Symposium and Gala Celebration c/o Metanexus Institute 3624 Market Street, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA 19104 215.789.2200, [email protected] www.foundationalquestions.net/townes Saturday, October 8, 2005 We explore. What path to explore is important, as well as what we notice along the path. And there are always unturned stones along even well-trod paths. Discovery awaits those who spot and take the trouble to turn the stones. -- Charles H. Townes Table of Contents Table of Contents.............................................................................................................. 3 Welcome Letter................................................................................................................. 5 Conference Supporters and Organizers ............................................................................ 7 Sponsors.......................................................................................................................... 13 Program Agenda ............................................................................................................. 29 Amazing Light Young Scholars Competition................................................................. 37 Amazing Light Laser Challenge Website Competition.................................................. 41 Foundational -

Applications in Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Physics

On Fer and Floquet-Magnus Expansions: Applications in Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Physics Eugene Stephane Mananga The City University of New York New York University International Conference on Physics June 27-29, 2016 New Orleans, LA, USA OUTLINE A. Background of NMR: Solid-State NMR • Principal References B. Commonly Used Methods in Solid-State NMR • Floquet Theory • Average Hamiltonian Theory C. Alternative Expansion Approaches Used Methods in SS-NMR • Fer Expansion • Floquet-Magnus Expansion D. Applications of Fer and Floquet-Magnus expansion in SS-SNMR E. Applications of Fer and Floquet-Magnus expansion in Physics A. Background of NMR: Solid-State NMR • NMR is an extraordinary versatile technique which started in Physics In 1945 and has spread with great success to Chemistry, Biochemistry, Biology, and Medicine, finding applications also in Geophysics, Archeology, Pharmacy, etc... • Hardly any discipline has remained untouched by NMR. • It is practiced in scientific labs everywhere, and no doubt before long will be found on the moon. • NMR has proved useful in elucidating problems in all forms of matter. In this talk we consider applications of NMR to solid state: Solid-State NMR BRIEF HISTORY OF NMR • 1920's Physicists Have Great Success With Quantum Theory • 1921 Stern and Gerlach Carry out Atomic and Molecular Beam Experiments • 1925/27 Schrödinger/ Heisenberg/ Dirac Formulate The New Quantum Mechanics • 1936 Gorter Attempts Experiments Using The Resonance Property of Nuclear Spin • 1937 Rabi Predicts and Observes -

Communications-Mathematics and Applied Mathematics/Download/8110

A Mathematician's Journey to the Edge of the Universe "The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing." ― Socrates Manjunath.R #16/1, 8th Main Road, Shivanagar, Rajajinagar, Bangalore560010, Karnataka, India *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] *Website: http://www.myw3schools.com/ A Mathematician's Journey to the Edge of the Universe What’s the Ultimate Question? Since the dawn of the history of science from Copernicus (who took the details of Ptolemy, and found a way to look at the same construction from a slightly different perspective and discover that the Earth is not the center of the universe) and Galileo to the present, we (a hoard of talking monkeys who's consciousness is from a collection of connected neurons − hammering away on typewriters and by pure chance eventually ranging the values for the (fundamental) numbers that would allow the development of any form of intelligent life) have gazed at the stars and attempted to chart the heavens and still discovering the fundamental laws of nature often get asked: What is Dark Matter? ... What is Dark Energy? ... What Came Before the Big Bang? ... What's Inside a Black Hole? ... Will the universe continue expanding? Will it just stop or even begin to contract? Are We Alone? Beginning at Stonehenge and ending with the current crisis in String Theory, the story of this eternal question to uncover the mysteries of the universe describes a narrative that includes some of the greatest discoveries of all time and leading personalities, including Aristotle, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton, and the rise to the modern era of Einstein, Eddington, and Hawking. -

LUIS ALVAREZ and the PYRAMID BURIAL CHAMBERS, the JFK ASSASSINATION, and the END of the DINOSAURS Charles G

SCIENTIST AS DETECTIVE: LUIS ALVAREZ AND THE PYRAMID BURIAL CHAMBERS, THE JFK ASSASSINATION, AND THE END OF THE DINOSAURS Charles G. Wohl Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720 Luis Alvarez (1911{1988) was one of the most brilliant and productive experimental physicists of the twentieth century. His investigations of three mysteries, all of them outside his normal areas of research, show the wonders that a far-ranging imagination working with an immense store of knowledge can accomplish. The 1968 Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded to Luis W. Alvarez: • \For his decisive contributions to elementary particle physics, in particular the discovery of a large number of resonant states, made possible through his devel- opment of the technique of using hydrogen bubble chambers and data analysis." Richard Feynman, considering whether or not to do the O-ring-in-ice-water demonstration• in the Challenger disaster hearings: \I think, `I could do this tomorrow while we're all sitting around, listening to this [Richard] Cook crap we heard today. We always get ice water in those meetings; that's something I could do to save time.' \Then I think, `No, that would be gauche.' \But then I think of Luis Alvarez, the physicist. He's a guy I admire for his gutsiness and sense of humor, and I think, `If Alvarez was on this commission, he would do it, and that's good enough for me.' "1 1. THE PYRAMID BURIAL CHAMBERS 2 Father and son|Figure 1 shows, near Cairo, the two largest pyramids ever built. They are 4,500 years old. -

Report and Opinion 2016;8(6) 1

Report and Opinion 2016;8(6) http://www.sciencepub.net/report Beyond Einstein and Newton: A Scientific Odyssey Through Creation, Higher Dimensions, And The Cosmos Manjunath R Independent Researcher #16/1, 8 Th Main Road, Shivanagar, Rajajinagar, Bangalore: 560010, Karnataka, India [email protected], [email protected] “There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now. All that remains is more and more precise measurement.” : Lord Kelvin Abstract: General public regards science as a beautiful truth. But it is absolutely-absolutely false. Science has fatal limitations. The whole the scientific community is ignorant about it. It is strange that scientists are not raising the issues. Science means truth, and scientists are proponents of the truth. But they are teaching incorrect ideas to children (upcoming scientists) in schools /colleges etc. One who will raise the issue will face unprecedented initial criticism. Anyone can read the book and find out the truth. It is open to everyone. [Manjunath R. Beyond Einstein and Newton: A Scientific Odyssey Through Creation, Higher Dimensions, And The Cosmos. Rep Opinion 2016;8(6):1-81]. ISSN 1553-9873 (print); ISSN 2375-7205 (online). http://www.sciencepub.net/report. 1. doi:10.7537/marsroj08061601. Keywords: Science; Cosmos; Equations; Dimensions; Creation; Big Bang. “But the creative principle resides in Subaltern notable – built on the work of the great mathematics. In a certain sense, therefore, I hold it astronomers Galileo Galilei, Nicolaus Copernicus true that pure thought can -

Dr. Richard Feynman Nobel Laureatel

EXTRA! California Tech EXTRA! Associated Students of the Califorl'lia Institute of Technology Volume LXVII Pasadena, California, Friday, October 22, 1965 Number 5V2 Dr. Richard Feynman Nobel Laureatel October 21, 1965 (9 a.m.) Professor Richard Feynman: Royal Academs of Sciences today awarded you and Tomonaga and Schwinger jointly the 1965 Nobel Prize for physics for your fundamental work in quantum electrody· namics with deep ploughing consequences for the physics of elementary particles.' Prize money each one·third. Our warm congratulations. Letter will follow. Erik Rundberg The Permanent Secretary Erik Rundberg: Your cablegram has made me very happy! Richard P. Feynman Earlier, at 3:45 a.m.: "'Hello, Dr. Richard Feynman? May I congratulate you on your Nobel Prize.' "Look. This is a heck of an hour "'But aren't you pleased to hear that you've won the Prize?' "I could have found out later this morn ing. "'Well, how do you feel, now that you've "And so he se:z:, 'Can you explain in a few words just what you did to win the Pri:z:e?' So 1 say, 'I won it?' made marks on a piece of paper:" "Look, some other time . " And so Richard P. Feynman, PhD, FRS, through second-order approximations led to going to be a mess. and Richard Chace Tolman Professor of infinite solutions. What the three Nobel '" Well, I'm going to ask you also to Theoretical Physics at Caltech, first sleepily Prize winners did, in the words of Feyn comment on the statement that your work learned that he was an awardee of the 1965 man, was "to get rid of the infinities in the was to convert experi.mental data on Nobel Prize in physics. -

When Physics Meets Biology: a Less Known Feynman

When physics meets biology: a less known Feynman Marco Di Mauro, Salvatore Esposito, and Adele Naddeo INFN Sezione di Napoli, Naples - 80126, Italy We discuss a less known aspect of Feynman’s multifaceted scientific work, centered about his interest in molecular biology, which came out around 1959 and lasted for several years. After a quick historical reconstruction about the birth of molecular biology, we focus on Feynman’s work on genetics with Robert S. Edgar in the laboratory of Max Delbruck, which was later quoted by Francis Crick and others in relevant papers, as well as in Feynman’s lectures given at the Hughes Aircraft Company on biology, organic chemistry and microbiology, whose notes taken by the attendee John Neer are available. An intriguing perspective comes out about one of the most interesting scientists of the XX century. 1. INTRODUCTION Richard P. Feynman has been – no doubt – one of the most intriguing characters of XX century physics (Mehra 1994). As well known to any interested people, this applies not only to his work as a theoretical physicist – ranging from the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics to quantum electrodynamics (granting him the Nobel prize in Physics in 1965), and from helium superfluidity to the parton model in particle physics –, but also to his own life, a number of anecdotes being present in the literature (Mehra 1994; Gleick 1992; Brown and Rigden 1993; Sykes 1994; Gribbin and Gribbin 1997; Leighton 2000; Mlodinov 2003; Feynman 2005; Henderson 2011; Krauss 2001), including his own popular -

The Miracle of Applied Mathematics

MARK COLYVAN THE MIRACLE OF APPLIED MATHEMATICS ABSTRACT. Mathematics has a great variety of applications in the physical sciences. This simple, undeniable fact, however, gives rise to an interesting philosophical problem: why should physical scientists find that they are unable to even state their theories without the resources of abstract mathematical theories? Moreover, the formulation of physical theories in the language of mathematics often leads to new physical predictions which were quite unexpected on purely physical grounds. It is thought by some that the puzzles the applications of mathematics present are artefacts of out-dated philosophical theories about the nature of mathematics. In this paper I argue that this is not so. I outline two contemporary philosophical accounts of mathematics that pay a great deal of attention to the applicability of mathematics and show that even these leave a large part of the puzzles in question unexplained. 1. THE UNREASONABLE EFFECTIVENESS OF MATHEMATICS The physicist Eugene Wigner once remarked that [t]he miracle of the appropriateness of the language of mathematics for the formulation of the laws of physics is a wonderful gift which we neither understand nor deserve. (Wigner 1960, 14) Steven Weinberg is another physicist who finds the applicability of mathematics puzzling: It is very strange that mathematicians are led by their sense of mathematical beauty to de- velop formal structures that physicists only later find useful, even where the mathematician had no such goal in mind. [ . ] Physicists generally find the ability of mathematicians to anticipate the mathematics needed in the theories of physics quite uncanny. It is as if Neil Armstrong in 1969 when he first set foot on the surface of the moon had found in the lunar dust the footsteps of Jules Verne.