Hans A. Bethe (1906-2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuclear Technology

Nuclear Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. GREENWOOD PRESS NUCLEAR TECHNOLOGY Sourcebooks in Modern Technology Space Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. Sourcebooks in Modern Technology Nuclear Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Angelo, Joseph A. Nuclear technology / Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. p. cm.—(Sourcebooks in modern technology) Includes index. ISBN 1–57356–336–6 (alk. paper) 1. Nuclear engineering. I. Title. II. Series. TK9145.A55 2004 621.48—dc22 2004011238 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2004 by Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004011238 ISBN: 1–57356–336–6 First published in 2004 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 To my wife, Joan—a wonderful companion and soul mate Contents Preface ix Chapter 1. History of Nuclear Technology and Science 1 Chapter 2. Chronology of Nuclear Technology 65 Chapter 3. Profiles of Nuclear Technology Pioneers, Visionaries, and Advocates 95 Chapter 4. How Nuclear Technology Works 155 Chapter 5. Impact 315 Chapter 6. Issues 375 Chapter 7. The Future of Nuclear Technology 443 Chapter 8. Glossary of Terms Used in Nuclear Technology 485 Chapter 9. Associations 539 Chapter 10. -

Annual Report 2013.Pdf

ATOMIC HERITAGE FOUNDATION Preserving & Interpreting Manhattan Project History & Legacy preserving history ANNUAL REPORT 2013 WHY WE SHOULD PRESERVE THE MANHATTAN PROJECT “The factories and bombs that Manhattan Project scientists, engineers, and workers built were physical objects that depended for their operation on physics, chemistry, metallurgy, and other nat- ural sciences, but their social reality - their meaning, if you will - was human, social, political....We preserve what we value of the physical past because it specifically embodies our social past....When we lose parts of our physical past, we lose parts of our common social past as well.” “The new knowledge of nuclear energy has undoubtedly limited national sovereignty and scaled down the destructiveness of war. If that’s not a good enough reason to work for and contribute to the Manhattan Project’s historic preservation, what would be? It’s certainly good enough for me.” ~Richard Rhodes, “Why We Should Preserve the Manhattan Project,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May/June 2006 Photographs clockwise from top: J. Robert Oppenheimer, General Leslie R. Groves pinning an award on Enrico Fermi, Leona Woods Marshall, the Alpha Racetrack at the Y-12 Plant, and the Bethe House on Bathtub Row. Front cover: A Bruggeman Ranch property. Back cover: Bronze statues by Susanne Vertel of J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves at Los Alamos. Table of Contents BOARD MEMBERS & ADVISORY COMMITTEE........3 Cindy Kelly, Dorothy and Clay Per- Letter from the President..........................................4 -

The Physical Tourist Physics and New York City

Phys. perspect. 5 (2003) 87–121 © Birkha¨user Verlag, Basel, 2003 1422–6944/05/010087–35 The Physical Tourist Physics and New York City Benjamin Bederson* I discuss the contributions of physicists who have lived and worked in New York City within the context of the high schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions with which they were and are associated. I close with a walking tour of major sites of interest in Manhattan. Key words: Thomas A. Edison; Nikola Tesla; Michael I. Pupin; Hall of Fame for GreatAmericans;AlbertEinstein;OttoStern;HenryGoldman;J.RobertOppenheimer; Richard P. Feynman; Julian Schwinger; Isidor I. Rabi; Bronx High School of Science; StuyvesantHighSchool;TownsendHarrisHighSchool;NewYorkAcademyofSciences; Andrei Sakharov; Fordham University; Victor F. Hess; Cooper Union; Peter Cooper; City University of New York; City College; Brooklyn College; Melba Phillips; Hunter College; Rosalyn Yalow; Queens College; Lehman College; New York University; Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences; Samuel F.B. Morse; John W. Draper; Columbia University; Polytechnic University; Manhattan Project; American Museum of Natural History; Rockefeller University; New York Public Library. Introduction When I was approached by the editors of Physics in Perspecti6e to prepare an article on New York City for The Physical Tourist section, I was happy to do so. I have been a New Yorker all my life, except for short-term stays elsewhere on sabbatical leaves and other visits. My professional life developed in New York, and I married and raised my family in New York and its environs. Accordingly, writing such an article seemed a natural thing to do. About halfway through its preparation, however, the attack on the World Trade Center took place. -

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman Louis de Broglie Norman Ramsey Willis Lamb Otto Stern Werner Heisenberg Walther Gerlach Ernest Rutherford Satyendranath Bose Max Born Erwin Schrödinger Eugene Wigner Arnold Sommerfeld Julian Schwinger David Bohm Enrico Fermi Albert Einstein Where discovery meets practice Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology IQ ST in Baden-Württemberg . Introduction “But I do not wish to be forced into abandoning strict These two quotes by Albert Einstein not only express his well more securely, develop new types of computer or construct highly causality without having defended it quite differently known aversion to quantum theory, they also come from two quite accurate measuring equipment. than I have so far. The idea that an electron exposed to a different periods of his life. The first is from a letter dated 19 April Thus quantum theory extends beyond the field of physics into other 1924 to Max Born regarding the latter’s statistical interpretation of areas, e.g. mathematics, engineering, chemistry, and even biology. beam freely chooses the moment and direction in which quantum mechanics. The second is from Einstein’s last lecture as Let us look at a few examples which illustrate this. The field of crypt it wants to move is unbearable to me. If that is the case, part of a series of classes by the American physicist John Archibald ography uses number theory, which constitutes a subdiscipline of then I would rather be a cobbler or a casino employee Wheeler in 1954 at Princeton. pure mathematics. Producing a quantum computer with new types than a physicist.” The realization that, in the quantum world, objects only exist when of gates on the basis of the superposition principle from quantum they are measured – and this is what is behind the moon/mouse mechanics requires the involvement of engineering. -

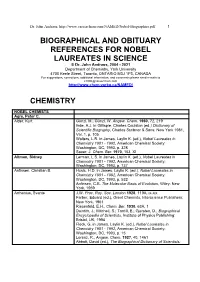

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Luis Alvarez: the Ideas Man

CERN Courier March 2012 Commemoration Luis Alvarez: the ideas man The years from the early 1950s to the late 1980s came alive again during a symposium to commemorate the birth of one of the great scientists and inventors of the 20th century. Luis Alvarez – one of the greatest experimental physicists of the 20th century – combined the interests of a scientist, an inventor, a detective and an explorer. He left his mark on areas that ranged from radar through to cosmic rays, nuclear physics, particle accel- erators, detectors and large-scale data analysis, as well as particles and astrophysics. On 19 November, some 200 people gathered at Berkeley to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth. Alumni of the Alvarez group – among them physicists, engineers, programmers and bubble-chamber film scanners – were joined by his collaborators, family, present-day students and admirers, as well as scientists whose professional lineage traces back to him. Hosted by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) and the University of California at Berkeley, the symposium reviewed his long career and lasting legacy. A recurring theme of the symposium was, as one speaker put it, a “Shakespeare-type dilemma”: how could one person have accom- plished all of that in one lifetime? Beyond his own initiatives, Alvarez created a culture around him that inspired others to, as George Smoot put it, “think big,” as well as to “think broadly and then deep” and to take risks. Combined with Alvarez’s strong scientific standards and great care in execut- ing them, these principles led directly to the awarding of two Nobel Luis Alvarez celebrating the announcement of his 1968 Nobel prizes in physics to scientists at Berkeley – George Smoot in 2006 prize. -

11/03/11 110311 Pisp.Doc Physics in the Interest of Society 1

1 _11/03/11_ 110311 PISp.doc Physics in the Interest of Society Physics in the Interest of Society Richard L. Garwin IBM Fellow Emeritus IBM, Thomas J. Watson Research Center Yorktown Heights, NY 10598 www.fas.org/RLG/ www.garwin.us [email protected] Inaugural Lecture of the Series Physics in the Interest of Society Massachusetts Institute of Technology November 3, 2011 2 _11/03/11_ 110311 PISp.doc Physics in the Interest of Society In preparing for this lecture I was pleased to reflect on outstanding role models over the decades. But I felt like the centipede that had no difficulty in walking until it began to think which leg to put first. Some of these things are easier to do than they are to describe, much less to analyze. Moreover, a lecture in 2011 is totally different from one of 1990, for instance, because of the instant availability of the Web where you can check or supplement anything I say. It really comes down to the comment of one of Elizabeth Taylor later spouses-to-be, when asked whether he was looking forward to his wedding, and replied, “I know what to do, but can I make it interesting?” I’ll just say first that I think almost all Physics is in the interest of society, but I take the term here to mean advising and consulting, rather than university, national lab, or contractor research. I received my B.S. in physics from what is now Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland in 1947 and went to Chicago with my new wife for graduate study in Physics. -

![I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8589/i-i-rabi-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-tue-apr-428589.webp)

I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr

I. I. Rabi Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1992 Revised 2010 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms998009 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm89076467 Prepared by Joseph Sullivan with the assistance of Kathleen A. Kelly and John R. Monagle Collection Summary Title: I. I. Rabi Papers Span Dates: 1899-1989 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1945-1968) ID No.: MSS76467 Creator: Rabi, I. I. (Isador Isaac), 1898- Extent: 41,500 items ; 105 cartons plus 1 oversize plus 4 classified ; 42 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Physicist and educator. The collection documents Rabi's research in physics, particularly in the fields of radar and nuclear energy, leading to the development of lasers, atomic clocks, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and to his 1944 Nobel Prize in physics; his work as a consultant to the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory and as an advisor on science policy to the United States government, the United Nations, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization during and after World War II; and his studies, research, and professorships in physics chiefly at Columbia University and also at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. -

Richard P. Feynman Author

Title: The Making of a Genius: Richard P. Feynman Author: Christian Forstner Ernst-Haeckel-Haus Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Berggasse 7 D-07743 Jena Germany Fax: +49 3641 949 502 Email: [email protected] Abstract: In 1965 the Nobel Foundation honored Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, Julian Schwinger, and Richard Feynman for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics and the consequences for the physics of elementary particles. In contrast to both of his colleagues only Richard Feynman appeared as a genius before the public. In his autobiographies he managed to connect his behavior, which contradicted several social and scientific norms, with the American myth of the “practical man”. This connection led to the image of a common American with extraordinary scientific abilities and contributed extensively to enhance the image of Feynman as genius in the public opinion. Is this image resulting from Feynman’s autobiographies in accordance with historical facts? This question is the starting point for a deeper historical analysis that tries to put Feynman and his actions back into historical context. The image of a “genius” appears then as a construct resulting from the public reception of brilliant scientific research. Introduction Richard Feynman is “half genius and half buffoon”, his colleague Freeman Dyson wrote in a letter to his parents in 1947 shortly after having met Feynman for the first time.1 It was precisely this combination of outstanding scientist of great talent and seeming clown that was conducive to allowing Feynman to appear as a genius amongst the American public. Between Feynman’s image as a genius, which was created significantly through the representation of Feynman in his autobiographical writings, and the historical perspective on his earlier career as a young aspiring physicist, a discrepancy exists that has not been observed in prior biographical literature. -

SHELDON LEE GLASHOW Lyman Laboratory of Physics Harvard University Cambridge, Mass., USA

TOWARDS A UNIFIED THEORY - THREADS IN A TAPESTRY Nobel Lecture, 8 December, 1979 by SHELDON LEE GLASHOW Lyman Laboratory of Physics Harvard University Cambridge, Mass., USA INTRODUCTION In 1956, when I began doing theoretical physics, the study of elementary particles was like a patchwork quilt. Electrodynamics, weak interactions, and strong interactions were clearly separate disciplines, separately taught and separately studied. There was no coherent theory that described them all. Developments such as the observation of parity violation, the successes of quantum electrodynamics, the discovery of hadron resonances and the appearance of strangeness were well-defined parts of the picture, but they could not be easily fitted together. Things have changed. Today we have what has been called a “standard theory” of elementary particle physics in which strong, weak, and electro- magnetic interactions all arise from a local symmetry principle. It is, in a sense, a complete and apparently correct theory, offering a qualitative description of all particle phenomena and precise quantitative predictions in many instances. There is no experimental data that contradicts the theory. In principle, if not yet in practice, all experimental data can be expressed in terms of a small number of “fundamental” masses and cou- pling constants. The theory we now have is an integral work of art: the patchwork quilt has become a tapestry. Tapestries are made by many artisans working together. The contribu- tions of separate workers cannot be discerned in the completed work, and the loose and false threads have been covered over. So it is in our picture of particle physics. Part of the picture is the unification of weak and electromagnetic interactions and the prediction of neutral currents, now being celebrated by the award of the Nobel Prize. -

Chem 103, Section F0F Unit I

Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Chem 103, Section F0F Nuclear Model of the Atom Unit I - An Overview of Chemistry Dalton’s theory proposed that atoms were indivisible particles. Lecture 4 • By the late 19th century, this aspect of Dalton’s theory was being challenged. • Work with electricity lead to the discovery of the electron, • Some observations that led to the nuclear model as a particle that carried a negative charge. for the structure of the atom • The modern view of the atomic structure and the elements • Arranging the elements into a (periodic) table 2 Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Nuclear Model of the Atom Nuclear Model of the Atom The cathode ray In 1897, J.J. Thomson (1856-1940) studies how cathode rays • Cathode rays were shown to be electrons are affected by electric and magnetic fields • This allowed him to determine the mass/charge ration of an electron Cathode rays are released by metals at the cathode 3 4 Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Nuclear Model of the Atom Nuclear Model of the Atom In 1897, J.J. Thomson (1856-1940) studies how cathode rays In 1897, J.J. Thomson (1856-1940) studies how cathode rays are affected by electric and magnetic fields are affected by electric and magnetic fields • Thomson estimated that the mass of an electron was less • Thomson received the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physics for his that 1/1000 the mass of the lightest atom, hydrogen!! work. -

Enrico Fermi

Fermi, Enrico Inventors and Inventions Enrico Fermi Italian American physicist Fermi helped develop Fermi-Dirac statistics, which liceo (secondary school) and, on the advice of Amidei, elucidate the group behavior of elementary particles. joined the Scuola Normale Superiore at Pisa. This elite He also developed the theory of beta decay and college, attached to the University of Pisa, admitted only discovered neutron-induced artificial radioactivity. forty of Italy’s top students, who were given free board Finally, he succeeded in producing the first sustained and lodging. Fermi performed exceedingly well in the nuclear chain reaction, which led to the discovery highly competitive entrance exam. He completed his of nuclear energy and the development of the university education after only four years of research and atomic bomb. studies, receiving his Ph.D. in physics from the Univer- sity of Pisa and his undergraduate diploma from the Born: September 29, 1901; Rome, Italy Scuola Normale Superiore in July, 1922. He became Died: November 28, 1954; Chicago, Illinois an expert theoretical physicist and a talented exper- Primary field: Physics imentalist. This rare combination provided a solid foun- Primary inventions: Controlled nuclear chain dation for all his subsequent inventions. reaction; Fermi-Dirac statistics; theory of beta decay Life’s Work After postdoctoral work at the University of Göttingen, Early Life in Germany (1922-1923), and the University of Leiden, Enrico Fermi (ehn-REE-koh FUR-mee) was the third in the Netherlands (fall, 1924), Fermi took an interim po- child of Alberto Fermi and Ida de Gattis. Enrico was very sition at the University of Florence in December, 1924.