Applications in Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fotonica Ed Elettronica Quantistica

Fotonica ed elettronica quantistica http://www.dsf.unica.it/~fotonica/teaching/fotonica.html Fotonica ed elettronica quantistica Quantum optics - Quantization of electromagnetic field - Statistics of light, photon counting and noise; - HBT and correlation; g1 e g2 coherence; antibunching; single photons - Squeezing - Quantum cryptography - Quantum computer, entanglement and teleportation Light-matter Interaction - Two-level atom - Laser physics - Spectroscopy - Electronics and photonics at the nanometer scale - Cold atoms - Photodetectors - Solar cells http://www.dsf.unica.it/~fotonica/teaching/fotonica.html Energy Temperature LHC at CERN, Higgs, SUSY, ??? TeV 15 q q particle accelerators 10 K q GeV proton rest mass - quarks 1012K MeV electron rest mass / gamma rays 109K keV Nuclear Fusion, x rays, Sun center 106K Atoms ionize - visible light eV Sun surface fundamental components components fundamental room temperature 103K meV Liquid He, superconductors, space 1K dilution refrigerators, quantum Hall µeV laser-cooled atoms 10-3K neV Bose-Einstein condensates 10-6K peV low T record 480 picokelvin 10-9K -12 complexity, organization organization complexity, 10 K Nobel Prizes in Physics 2010 - Andre Geims, Konstantin Novoselov 2009 - Charles K. Kao, Willard S. Boyle, George E. Smith 2007 - Albert Fert, Peter Gruenberg 2005 - Roy J. Glauber, John L. Hall, Theodor W. Hänsch 2001 - Eric A. Cornell, Wolfgang Ketterle, Carl E. Wieman 1997 - Steven Chu, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, William D. Phillips 1989 - Norman F. Ramsey, Hans G. Dehmelt, Wolfgang Paul 1981 - Nicolaas Bloembergen, Arthur L. Schawlow, Kai M. Siegbahn 1966 - Alfred Kastler 1964 - Charles H. Townes, Nicolay G. Basov, Aleksandr M. Prokhorov 1944 - Isidor Isaac Rabi 1930 - Venkata Raman 1921 - Albert Einstein 1907 - Albert A. -

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman Louis de Broglie Norman Ramsey Willis Lamb Otto Stern Werner Heisenberg Walther Gerlach Ernest Rutherford Satyendranath Bose Max Born Erwin Schrödinger Eugene Wigner Arnold Sommerfeld Julian Schwinger David Bohm Enrico Fermi Albert Einstein Where discovery meets practice Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology IQ ST in Baden-Württemberg . Introduction “But I do not wish to be forced into abandoning strict These two quotes by Albert Einstein not only express his well more securely, develop new types of computer or construct highly causality without having defended it quite differently known aversion to quantum theory, they also come from two quite accurate measuring equipment. than I have so far. The idea that an electron exposed to a different periods of his life. The first is from a letter dated 19 April Thus quantum theory extends beyond the field of physics into other 1924 to Max Born regarding the latter’s statistical interpretation of areas, e.g. mathematics, engineering, chemistry, and even biology. beam freely chooses the moment and direction in which quantum mechanics. The second is from Einstein’s last lecture as Let us look at a few examples which illustrate this. The field of crypt it wants to move is unbearable to me. If that is the case, part of a series of classes by the American physicist John Archibald ography uses number theory, which constitutes a subdiscipline of then I would rather be a cobbler or a casino employee Wheeler in 1954 at Princeton. pure mathematics. Producing a quantum computer with new types than a physicist.” The realization that, in the quantum world, objects only exist when of gates on the basis of the superposition principle from quantum they are measured – and this is what is behind the moon/mouse mechanics requires the involvement of engineering. -

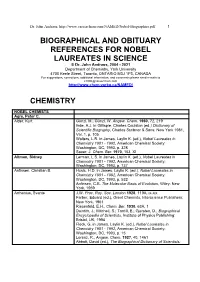

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

![I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8589/i-i-rabi-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-tue-apr-428589.webp)

I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr

I. I. Rabi Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1992 Revised 2010 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms998009 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm89076467 Prepared by Joseph Sullivan with the assistance of Kathleen A. Kelly and John R. Monagle Collection Summary Title: I. I. Rabi Papers Span Dates: 1899-1989 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1945-1968) ID No.: MSS76467 Creator: Rabi, I. I. (Isador Isaac), 1898- Extent: 41,500 items ; 105 cartons plus 1 oversize plus 4 classified ; 42 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Physicist and educator. The collection documents Rabi's research in physics, particularly in the fields of radar and nuclear energy, leading to the development of lasers, atomic clocks, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and to his 1944 Nobel Prize in physics; his work as a consultant to the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory and as an advisor on science policy to the United States government, the United Nations, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization during and after World War II; and his studies, research, and professorships in physics chiefly at Columbia University and also at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. -

Richard P. Feynman Author

Title: The Making of a Genius: Richard P. Feynman Author: Christian Forstner Ernst-Haeckel-Haus Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Berggasse 7 D-07743 Jena Germany Fax: +49 3641 949 502 Email: [email protected] Abstract: In 1965 the Nobel Foundation honored Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, Julian Schwinger, and Richard Feynman for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics and the consequences for the physics of elementary particles. In contrast to both of his colleagues only Richard Feynman appeared as a genius before the public. In his autobiographies he managed to connect his behavior, which contradicted several social and scientific norms, with the American myth of the “practical man”. This connection led to the image of a common American with extraordinary scientific abilities and contributed extensively to enhance the image of Feynman as genius in the public opinion. Is this image resulting from Feynman’s autobiographies in accordance with historical facts? This question is the starting point for a deeper historical analysis that tries to put Feynman and his actions back into historical context. The image of a “genius” appears then as a construct resulting from the public reception of brilliant scientific research. Introduction Richard Feynman is “half genius and half buffoon”, his colleague Freeman Dyson wrote in a letter to his parents in 1947 shortly after having met Feynman for the first time.1 It was precisely this combination of outstanding scientist of great talent and seeming clown that was conducive to allowing Feynman to appear as a genius amongst the American public. Between Feynman’s image as a genius, which was created significantly through the representation of Feynman in his autobiographical writings, and the historical perspective on his earlier career as a young aspiring physicist, a discrepancy exists that has not been observed in prior biographical literature. -

More Eugene Wigner Stories; Response to a Feynman Claim (As Published in the Oak Ridger’S Historically Speaking Column on August 29, 2016)

More Eugene Wigner stories; Response to a Feynman claim (As published in The Oak Ridger’s Historically Speaking column on August 29, 2016) Carolyn Krause has collected a couple more stories about Eugene Wigner, plus a response by Y- 12 to allegations by Richard Feynman in a book that included a story on his experience at Y-12 during World War II. … Mary Ann Davidson, widow of Jack Davidson, a longtime member of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Instrumentation and Controls Division, told me about Jack’s encounter with Wigner one day. Once Eugene Wigner had trouble opening his briefcase while visiting ORNL. He was referred to Jack Davidson in the old Instrumentation and Controls Division. Jack managed to open it for him. As was his custom, Wigner asked Jack about his research. Jack, who later won an R&D-100 award, said he was building a camera that will imitate a fly’s eye; in other words, it will capture light coming from a variety of directions. The topic of television and TV cameras came up. Wigner said he wondered how TV works. So Davidson explained the concept to him. Charles Jones told me this story about Eugene Wigner when he visited ORNL in the 1980s. Jones, who was technical director of the Holifield Heavy Ion Research Facility, said he invited Wigner to accompany him to the top of the HHIRF tower, and Wigner happily accepted the offer. At the top Wigner looked down at all the ORNL buildings, most of which had been constructed after he was the lab’s research director in 1946-47. -

Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for nuclear research and instrumentation. The field has spun off: particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, nuclear power reactors, nuclear medicine, and nuclear weapons. Understanding how the nucleus works and applying that knowledge to technology has been one of the most significant accomplishments of twentieth century scientific research. Each prize was awarded for physics unless otherwise noted. Name(s) Discovery Year Henri Becquerel, Pierre Discovered spontaneous radioactivity 1903 Curie, and Marie Curie Ernest Rutherford Work on the disintegration of the elements and 1908 chemistry of radioactive elements (chem) Marie Curie Discovery of radium and polonium 1911 (chem) Frederick Soddy Work on chemistry of radioactive substances 1921 including the origin and nature of radioactive (chem) isotopes Francis Aston Discovery of isotopes in many non-radioactive 1922 elements, also enunciated the whole-number rule of (chem) atomic masses Charles Wilson Development of the cloud chamber for detecting 1927 charged particles Harold Urey Discovery of heavy hydrogen (deuterium) 1934 (chem) Frederic Joliot and Synthesis of several new radioactive elements 1935 Irene Joliot-Curie (chem) James Chadwick Discovery of the neutron 1935 Carl David Anderson Discovery of the positron 1936 Enrico Fermi New radioactive elements produced by neutron 1938 irradiation Ernest Lawrence -

The Adventures of a Citizen Scientist

The Adventures of a Citizen Scientist Perhaps one never knows one’s parents, really knows them. You never know their early lives and, as a kid, you’re living inside your own skin, not theirs. After that you’re out of there. Growing up in Chicago, I never knew my dad was famous. He was just a firm, affectionate, if too busy father figure, who loved music and the outdoors, played tennis better than I could, was awfully good with tools, and could explain scientific ideas so well that I almost understood them. I knew he was a physicist and taught at the University, and he and mother often took me on lecture or research trips, but I didn’t know what it was all about. During the war, when he was one of those in charge of the bomb project and we’d moved to Oak Ridge, he was just a hard-working ordinary man doing a job like everybody else. August 6th, 1945, brought a dramatically different perspective, as you might expect. My father was suddenly a national and world figure. That fall, as I went off to college, I began to hear something of his achievements — not only the bomb, but the cosmic ray studies and the Nobel Prize, with all that seemed to entail. At that moment, too, he’d become Chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis, and my college was his college, where his father had been Professor of Philosophy and Psychology and Dean. I was in Wooster, Ohio, the town in which my father had grown up, with his childhood house just down College Avenue. -

A Pedagogical Approach to the Magnus Expansion

Home Search Collections Journals About Contact us My IOPscience A pedagogical approach to the Magnus expansion This article has been downloaded from IOPscience. Please scroll down to see the full text article. 2010 Eur. J. Phys. 31 907 (http://iopscience.iop.org/0143-0807/31/4/020) View the table of contents for this issue, or go to the journal homepage for more Download details: IP Address: 147.156.163.88 The article was downloaded on 16/06/2010 at 13:36 Please note that terms and conditions apply. IOP PUBLISHING EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICS Eur. J. Phys. 31 (2010) 907–918 doi:10.1088/0143-0807/31/4/020 A pedagogical approach to the Magnus expansion S Blanes1, F Casas2,JAOteo3 and J Ros4 1 Instituto de Matematica´ Multidisciplinar, Universidad Politecnica´ de Valencia, E-46022 Valencia, Spain 2 Departament de Matematiques,` Universitat Jaume I, E-12071 Castellon,´ Spain 3 Departament de F´ısica Teorica,` Universitat de Valencia,` 46100-Burjassot, Valencia,` Spain 4 Departament de F´ısica Teorica` and Instituto de F´ısica Corpuscular (IFIC), Universitat de Valencia,` 46100-Burjassot, Valencia,` Spain E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected] Received 26 April 2010, in final form 14 May 2010 Published 16 June 2010 Online at stacks.iop.org/EJP/31/907 Abstract Time-dependent perturbation theory as a tool to compute approximate solutions of the Schrodinger¨ equation does not preserve unitarity. Here we present, in a simple way, how the Magnus expansion (also known as exponential perturbation theory) provides such unitary approximate solutions. -

Prelim Reading List for Modern Physical Science (Last Updated: February 27, 2006)

Prelim Reading List for Modern Physical Science (last updated: February 27, 2006) Proposed preliminary examination reading list for Dana Freiburger. List of categories: 1 – Overview, Historiography, some ‘Classics’, and Survey Works 2.1 – 19th Century Physics 2.2 – 20th Century Physics 3 – Big Science 4 – Astronomy 5.1 – National Histories 5.2 – Atomic Weapons 6 – Sites of Research 7 – Instruments and Experiments 8 – Biography 9 – Japan Document History: 09/12/05 – First draft submitted to Richard 11/14/05 – Updated based on 10/12/05 meeting with Richard 02/27/06 – Updated to add categories to Endnote records, close to ‘final’ page 1 Prelim Reading List for Modern Physical Science (last updated: February 27, 2006) 1 – Overview, Historiography, some ‘Classics’, and Survey Works 01 Brown, Pais and Pippard, Twentieth century physics, 1995. 02 Cajori, A history of physics in its elementary branches (through 1925): including the evolution of physical laboratories, 1962. 03 Collins and Pinch, The Golem: What You Should Know About Science, 1998. 04 Dear, Revolutionizing the Sciences: European Knowledge and its Ambitions, 1500-1700, 2001. 05 Forman, The environment and practice of atomic physics in Weimar, Germany; a study in the history of science, 1968. 06 Fraser, The particle century, 1998. 07 Galison and Stump, The Disunity of Science: Boundaries, Contexts, and Power, 1996. 08 Kragh, Quantum Generations: a History of Physics in the Twentieth Century, 1999. 09 Kuhn, Black-body theory and the quantum discontinuity, 1894-1912, 1987. 10 Morus, When physics became king, 2005. 11 Nye, Before Big Science: the Pursuit of Modern Chemistry and Physics, 1800-1940, 1996. -

Works of Love

reader.ad section 9/21/05 12:38 PM Page 2 AMAZING LIGHT: Visions for Discovery AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM IN HONOR OF THE 90TH BIRTHDAY YEAR OF CHARLES TOWNES October 6-8, 2005 — University of California, Berkeley Amazing Light Symposium and Gala Celebration c/o Metanexus Institute 3624 Market Street, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA 19104 215.789.2200, [email protected] www.foundationalquestions.net/townes Saturday, October 8, 2005 We explore. What path to explore is important, as well as what we notice along the path. And there are always unturned stones along even well-trod paths. Discovery awaits those who spot and take the trouble to turn the stones. -- Charles H. Townes Table of Contents Table of Contents.............................................................................................................. 3 Welcome Letter................................................................................................................. 5 Conference Supporters and Organizers ............................................................................ 7 Sponsors.......................................................................................................................... 13 Program Agenda ............................................................................................................. 29 Amazing Light Young Scholars Competition................................................................. 37 Amazing Light Laser Challenge Website Competition.................................................. 41 Foundational -

Otto Stern Annalen 4.11.11

(To be published by Annalen der Physik in December 2011) Otto Stern (1888-1969): The founding father of experimental atomic physics J. Peter Toennies,1 Horst Schmidt-Böcking,2 Bretislav Friedrich,3 Julian C.A. Lower2 1Max-Planck-Institut für Dynamik und Selbstorganisation Bunsenstrasse 10, 37073 Göttingen 2Institut für Kernphysik, Goethe Universität Frankfurt Max-von-Laue-Strasse 1, 60438 Frankfurt 3Fritz-Haber-Institut der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft Faradayweg 4-6, 14195 Berlin Keywords History of Science, Atomic Physics, Quantum Physics, Stern- Gerlach experiment, molecular beams, space quantization, magnetic dipole moments of nucleons, diffraction of matter waves, Nobel Prizes, University of Zurich, University of Frankfurt, University of Rostock, University of Hamburg, Carnegie Institute. We review the work and life of Otto Stern who developed the molecular beam technique and with its aid laid the foundations of experimental atomic physics. Among the key results of his research are: the experimental test of the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution of molecular velocities (1920), experimental demonstration of space quantization of angular momentum (1922), diffraction of matter waves comprised of atoms and molecules by crystals (1931) and the determination of the magnetic dipole moments of the proton and deuteron (1933). 1 Introduction Short lists of the pioneers of quantum mechanics featured in textbooks and historical accounts alike typically include the names of Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Arnold Sommerfeld, Niels Bohr, Max von Laue, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, Paul Dirac, Max Born, and Wolfgang Pauli on the theory side, and of Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Ernest Rutherford, Arthur Compton, and James Franck on the experimental side. However, the records in the Archive of the Nobel Foundation as well as scientific correspondence, oral-history accounts and scientometric evidence suggest that at least one more name should be added to the list: that of the “experimenting theorist” Otto Stern.