When Physics Meets Biology: a Less Known Feynman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman

Wolfgang Pauli Niels Bohr Paul Dirac Max Planck Richard Feynman Louis de Broglie Norman Ramsey Willis Lamb Otto Stern Werner Heisenberg Walther Gerlach Ernest Rutherford Satyendranath Bose Max Born Erwin Schrödinger Eugene Wigner Arnold Sommerfeld Julian Schwinger David Bohm Enrico Fermi Albert Einstein Where discovery meets practice Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology IQ ST in Baden-Württemberg . Introduction “But I do not wish to be forced into abandoning strict These two quotes by Albert Einstein not only express his well more securely, develop new types of computer or construct highly causality without having defended it quite differently known aversion to quantum theory, they also come from two quite accurate measuring equipment. than I have so far. The idea that an electron exposed to a different periods of his life. The first is from a letter dated 19 April Thus quantum theory extends beyond the field of physics into other 1924 to Max Born regarding the latter’s statistical interpretation of areas, e.g. mathematics, engineering, chemistry, and even biology. beam freely chooses the moment and direction in which quantum mechanics. The second is from Einstein’s last lecture as Let us look at a few examples which illustrate this. The field of crypt it wants to move is unbearable to me. If that is the case, part of a series of classes by the American physicist John Archibald ography uses number theory, which constitutes a subdiscipline of then I would rather be a cobbler or a casino employee Wheeler in 1954 at Princeton. pure mathematics. Producing a quantum computer with new types than a physicist.” The realization that, in the quantum world, objects only exist when of gates on the basis of the superposition principle from quantum they are measured – and this is what is behind the moon/mouse mechanics requires the involvement of engineering. -

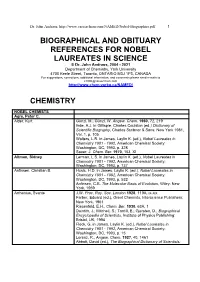

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Pandit Deendayal Petroleum University School of Liberal Studies

Pandit Deendayal Petroleum University School of Liberal Studies BSP302T Electricity and magnetism Teaching Scheme Examination Scheme Theory Practical Total L T P C Hrs/Week MS ES IA LW LE/Viva Marks 4 0 0 4 4 25 50 25 -- -- 100 COURSE OBJECTIVES To provide the basic understanding of vector calculus and its application in electricity and magnetism To develop understanding and to provide comprehensive knowledge in the field of electricity and magnetism. To develop the concepts of electromagnetic induction and related phenomena To introduce the Maxwell’s equations and understand its significance UNIT 1 REVIEW OF VECTOR CALCULUS 8 Hrs. Properties of vectors, Introduction to gradient, divergence, curl, Laplacian, Introduction to spherical polar and cylindrical coordinates, Stokes’ theorem and Gauss divergence theorem, Problem solving. UNIT 2 ELECTRICITY 14 Hrs. Coulomb’s law and principle of superposition. Gauss’s law and its applications. Electric potential and electrostatic energy Poisson’s and Laplace’s equations with simple examples, uniqueness theorem, boundary value problems, Properties of conductors, method of images Dielectrics- Polarization and bound charges, Displacement vector Lorentz force law (cycloidal motion in an electric and magnetic field). UNIT 3 MAGNETISM 16 Hrs. Magnetostatics- Biot & Savart’s law, Amperes law. Divergence and curl of magnetic field, Vector potential and concept of gauge, Calculation of vector potential for a finite straight conductor, infinite wire and for a uniform magnetic field, Magnetism in matter, -

Jewels in the Crown

Jewels in the crown CSHL’s 8 Nobel laureates Eight scientists who have worked at Cold Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria Spring Harbor Laboratory over its first 125 years have earned the ultimate Beginning in 1941, two scientists, both refugees of European honor, the Nobel Prize for Physiology fascism, began spending their summers doing research at Cold or Medicine. Some have been full- Spring Harbor. In this idyllic setting, the pair—who had full-time time faculty members; others came appointments elsewhere—explored the deep mystery of genetics to the Lab to do summer research by exploiting the simplicity of tiny viruses called bacteriophages, or a postdoctoral fellowship. Two, or phages, which infect bacteria. Max Delbrück and Salvador who performed experiments at Luria, original protagonists in what came to be called the Phage the Lab as part of the historic Group, were at the center of a movement whose members made Phage Group, later served as seminal discoveries that launched the revolutionary field of mo- Directors. lecular genetics. Their distinctive math- and physics-oriented ap- Peter Tarr proach to biology, partly a reflection of Delbrück’s physics train- ing, was propagated far and wide via the famous Phage Course that Delbrück first taught in 1945. The famous Luria-Delbrück experiment of 1943 showed that genetic mutations occur ran- domly in bacteria, not necessarily in response to selection. The pair also showed that resistance was a heritable trait in the tiny organisms. Delbrück and Luria, along with Alfred Hershey, were awarded a Nobel Prize in 1969 “for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses.” Barbara McClintock Alfred Hershey Today we know that “jumping genes”—transposable elements (TEs)—are littered everywhere, like so much Alfred Hershey first came to Cold Spring Harbor to participate in Phage Group wreckage, in the chromosomes of every organism. -

Aspin Bubbles Mechanical Project for the Unification of the Forces of Nature

Aspin Bubbles mechanical project for the unification of the forces of Nature Yoël Lana-Renault Departamento de Física Teórica. Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad de Zaragoza. 50009 - Zaragoza, Spain e-mail: [email protected] web: www.yoel-lana-renault.es This paper describes a mechanical theory for the unification of the basic forces of Nature with a single wave-particle interaction. The theory is based on the hypothesis that the ultimate components of matter are just two kind of pulsating particles. The interaction between these particles immersed in a fluid-like medium (ether) reproduces all the forces in Nature: electric, nuclear, gravitational, magnetic, atomic, van der Waals, Casimir, etc. The theory also designes the internal structure of the atom and of the fundamental particles that are currently known. Thus, a new concept of physics, capable of tackling entirely new problems, is introduced. Keywords: Unification of Forces, Non-linear Interactions. 1. Introduction Our theory presented here is compatible with existing views about the nature of matter, and demonstrates that the essential properties of particles can be described in the mechanical framework of classical physics with certain assumptions about the nature of physical space, which is traditionally called the ether. The theory is a synthesis of ideas used by Newton, Faraday, Maxwell and Einstein. In the past, the hypothesis of the ether as a fluid was decisive in the creation of the theory of the electromagnetic field. Vortex rings were used to construct a model of the atom at a time when the existence of elementary particles was not known. These days, applying vortex models to elementary particles looked reasonable. -

Richard P. Feynman Author

Title: The Making of a Genius: Richard P. Feynman Author: Christian Forstner Ernst-Haeckel-Haus Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Berggasse 7 D-07743 Jena Germany Fax: +49 3641 949 502 Email: [email protected] Abstract: In 1965 the Nobel Foundation honored Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, Julian Schwinger, and Richard Feynman for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics and the consequences for the physics of elementary particles. In contrast to both of his colleagues only Richard Feynman appeared as a genius before the public. In his autobiographies he managed to connect his behavior, which contradicted several social and scientific norms, with the American myth of the “practical man”. This connection led to the image of a common American with extraordinary scientific abilities and contributed extensively to enhance the image of Feynman as genius in the public opinion. Is this image resulting from Feynman’s autobiographies in accordance with historical facts? This question is the starting point for a deeper historical analysis that tries to put Feynman and his actions back into historical context. The image of a “genius” appears then as a construct resulting from the public reception of brilliant scientific research. Introduction Richard Feynman is “half genius and half buffoon”, his colleague Freeman Dyson wrote in a letter to his parents in 1947 shortly after having met Feynman for the first time.1 It was precisely this combination of outstanding scientist of great talent and seeming clown that was conducive to allowing Feynman to appear as a genius amongst the American public. Between Feynman’s image as a genius, which was created significantly through the representation of Feynman in his autobiographical writings, and the historical perspective on his earlier career as a young aspiring physicist, a discrepancy exists that has not been observed in prior biographical literature. -

![Max Ludwig Henning Delbruck (1906–1981) [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0999/max-ludwig-henning-delbruck-1906-1981-1-560999.webp)

Max Ludwig Henning Delbruck (1906–1981) [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Max Ludwig Henning Delbruck (1906–1981) [1] By: Hernandez, Victoria Max Ludwig Henning Delbrück applied his knowledge of theoretical physics to biological systems such as bacterial viruses called bacteriophages, or phages, and gene replication during the twentieth century in Germany and the US. Delbrück demonstrated that bacteria undergo random genetic mutations to resist phage infections. Those findings linked bacterial genetics to the genetics of higher organisms. In the mid-twentieth century, Delbrück helped start the Phage Group and Phage Course in the US, which further organized phage research. Delbrück also contributed to the DNA replication debate that culminated in the 1958 Meselson-Stahl experiment, which demonstrated how organisms replicate their genetic information. For his work with phages, Delbrück earned part of the 1969 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. Delbrück's work helped shape and establish new fields in molecular biology and genetics to investigate the laws of inheritance and development. Delbrück was born on 4 September 1906, as the last of seven children of Lina and Hans Delbrück, in Berlin, Germany. Delbrück grew up in Grunewald, a suburb of Berlin. In 1914, World War I [2] began. During the war, Delbrück's family struggled with food shortages and in 1917 Delbrück's oldest brother died in combat. After the war ended in 1918, Delbrück began to study astronomy. Some nights, Delbrück woke up in the middle of the night to observe the stars with his telescope. He also read about the seventeenth-century astronomer Johannes Kepler, who studied planetary motion in late sixteenth and early seventeenth century Germany. -

More Eugene Wigner Stories; Response to a Feynman Claim (As Published in the Oak Ridger’S Historically Speaking Column on August 29, 2016)

More Eugene Wigner stories; Response to a Feynman claim (As published in The Oak Ridger’s Historically Speaking column on August 29, 2016) Carolyn Krause has collected a couple more stories about Eugene Wigner, plus a response by Y- 12 to allegations by Richard Feynman in a book that included a story on his experience at Y-12 during World War II. … Mary Ann Davidson, widow of Jack Davidson, a longtime member of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Instrumentation and Controls Division, told me about Jack’s encounter with Wigner one day. Once Eugene Wigner had trouble opening his briefcase while visiting ORNL. He was referred to Jack Davidson in the old Instrumentation and Controls Division. Jack managed to open it for him. As was his custom, Wigner asked Jack about his research. Jack, who later won an R&D-100 award, said he was building a camera that will imitate a fly’s eye; in other words, it will capture light coming from a variety of directions. The topic of television and TV cameras came up. Wigner said he wondered how TV works. So Davidson explained the concept to him. Charles Jones told me this story about Eugene Wigner when he visited ORNL in the 1980s. Jones, who was technical director of the Holifield Heavy Ion Research Facility, said he invited Wigner to accompany him to the top of the HHIRF tower, and Wigner happily accepted the offer. At the top Wigner looked down at all the ORNL buildings, most of which had been constructed after he was the lab’s research director in 1946-47. -

Martha Chase Dies

PublisherInfo PublisherName : BioMed Central PublisherLocation : London PublisherImprintName : BioMed Central Martha Chase dies ArticleInfo ArticleID : 4830 ArticleDOI : 10.1186/gb-spotlight-20030820-01 ArticleCitationID : spotlight-20030820-01 ArticleSequenceNumber : 182 ArticleCategory : Research news ArticleFirstPage : 1 ArticleLastPage : 4 RegistrationDate : 2003–8–20 ArticleHistory : OnlineDate : 2003–8–20 ArticleCopyright : BioMed Central Ltd2003 ArticleGrants : ArticleContext : 130594411 Milly Dawson Email: [email protected] Martha Chase, renowned for her part in the pivotal "blender experiment," which firmly established DNA as the substance that transmits genetic information, died of pneumonia on August 8 in Lorain, Ohio. She was 75. In 1952, Chase participated in what came to be known as the Hershey-Chase experiment in her capacity as a laboratory assistant to Alfred D. Hershey. He won a Nobel Prize for his insights into the nature of viruses in 1969, along with Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria. Peter Sherwood, a spokesman for Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where the work took place, described the Hershey-Chase study as "one of the most simple and elegant experiments in the early days of the emerging field of molecular biology." "Her name would always be associated with that experiment, so she is some sort of monument," said her longtime friend Waclaw Szybalski, who met her when he joined Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1951 and who is now a professor of oncology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Szybalski attended the first staff presentation of the Hershey-Chase experiment and was so impressed that he invited Chase for dinner and dancing the same evening. "I had an impression that she did not realize what an important piece of work that she did, but I think that I convinced her that evening," he said. -

Works of Love

reader.ad section 9/21/05 12:38 PM Page 2 AMAZING LIGHT: Visions for Discovery AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM IN HONOR OF THE 90TH BIRTHDAY YEAR OF CHARLES TOWNES October 6-8, 2005 — University of California, Berkeley Amazing Light Symposium and Gala Celebration c/o Metanexus Institute 3624 Market Street, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA 19104 215.789.2200, [email protected] www.foundationalquestions.net/townes Saturday, October 8, 2005 We explore. What path to explore is important, as well as what we notice along the path. And there are always unturned stones along even well-trod paths. Discovery awaits those who spot and take the trouble to turn the stones. -- Charles H. Townes Table of Contents Table of Contents.............................................................................................................. 3 Welcome Letter................................................................................................................. 5 Conference Supporters and Organizers ............................................................................ 7 Sponsors.......................................................................................................................... 13 Program Agenda ............................................................................................................. 29 Amazing Light Young Scholars Competition................................................................. 37 Amazing Light Laser Challenge Website Competition.................................................. 41 Foundational -

Applications in Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Physics

On Fer and Floquet-Magnus Expansions: Applications in Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Physics Eugene Stephane Mananga The City University of New York New York University International Conference on Physics June 27-29, 2016 New Orleans, LA, USA OUTLINE A. Background of NMR: Solid-State NMR • Principal References B. Commonly Used Methods in Solid-State NMR • Floquet Theory • Average Hamiltonian Theory C. Alternative Expansion Approaches Used Methods in SS-NMR • Fer Expansion • Floquet-Magnus Expansion D. Applications of Fer and Floquet-Magnus expansion in SS-SNMR E. Applications of Fer and Floquet-Magnus expansion in Physics A. Background of NMR: Solid-State NMR • NMR is an extraordinary versatile technique which started in Physics In 1945 and has spread with great success to Chemistry, Biochemistry, Biology, and Medicine, finding applications also in Geophysics, Archeology, Pharmacy, etc... • Hardly any discipline has remained untouched by NMR. • It is practiced in scientific labs everywhere, and no doubt before long will be found on the moon. • NMR has proved useful in elucidating problems in all forms of matter. In this talk we consider applications of NMR to solid state: Solid-State NMR BRIEF HISTORY OF NMR • 1920's Physicists Have Great Success With Quantum Theory • 1921 Stern and Gerlach Carry out Atomic and Molecular Beam Experiments • 1925/27 Schrödinger/ Heisenberg/ Dirac Formulate The New Quantum Mechanics • 1936 Gorter Attempts Experiments Using The Resonance Property of Nuclear Spin • 1937 Rabi Predicts and Observes -

Communications-Mathematics and Applied Mathematics/Download/8110

A Mathematician's Journey to the Edge of the Universe "The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing." ― Socrates Manjunath.R #16/1, 8th Main Road, Shivanagar, Rajajinagar, Bangalore560010, Karnataka, India *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] *Website: http://www.myw3schools.com/ A Mathematician's Journey to the Edge of the Universe What’s the Ultimate Question? Since the dawn of the history of science from Copernicus (who took the details of Ptolemy, and found a way to look at the same construction from a slightly different perspective and discover that the Earth is not the center of the universe) and Galileo to the present, we (a hoard of talking monkeys who's consciousness is from a collection of connected neurons − hammering away on typewriters and by pure chance eventually ranging the values for the (fundamental) numbers that would allow the development of any form of intelligent life) have gazed at the stars and attempted to chart the heavens and still discovering the fundamental laws of nature often get asked: What is Dark Matter? ... What is Dark Energy? ... What Came Before the Big Bang? ... What's Inside a Black Hole? ... Will the universe continue expanding? Will it just stop or even begin to contract? Are We Alone? Beginning at Stonehenge and ending with the current crisis in String Theory, the story of this eternal question to uncover the mysteries of the universe describes a narrative that includes some of the greatest discoveries of all time and leading personalities, including Aristotle, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton, and the rise to the modern era of Einstein, Eddington, and Hawking.