Jewels in the Crown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

2002 President's Essay

from the 2002 Annual Report DIRECTOR’S REPORT Much has been written about the extraordinary events that took place in Cambridge, Eng - land, 50 years ago that changed biology forever. The discovery of the double-helical struc - ture of DNA ushered in an immediate future for understanding how genes are inherited, how genetic information is read, and how mutations are fixed in our genome. 2003 will ap - propriately celebrate the discovery and the stunning developments that have occurred since, not only in biology and medicine, but also in fields unanticipated by Jim Watson and Francis Crick when they proposed the double helix. DNA-based forensics is but one example, having an impact in the law to such an extent that some states are now reviewing whether capital punishment should be continued because of the possibility of irreversibly condemning the innocent. In all the writings and lore about the double-helix discovery, one of the little discussed points that struck me was the freedom that both Jim and Francis had to pursue what they felt was important, namely, the structure of DNA. Having completed graduate studies in the United States, Jim Watson went to Copenhagen to continue to become a biochemist in the hope that he might understand the gene, but he soon realized that biochemistry was not his forte. Most importantly, after hearing Maurice Wilkins talk about his early structural studies on DNA, Jim had the foresight that understanding DNA structure might help un - derstand the gene and therefore he decided to move to Cambridge, then, as now, a center of the field now known as structural biology. -

James D. Watson Molecular Biologist, Nobel Laureate ( 1928 – )

James D. Watson Molecular biologist, Nobel Laureate ( 1928 – ) Watson is a molecular biologist, best known as one of the co-discoverers of the struc- ture of DNA. Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Watson was born in Chicago, and early on showed his brilliance, appearing on Quiz Kids, a popular radio show that challenged precocious youngsters to answer ques- tions. Thanks to the liberal policy of University of Chicago president ROBERT HUTCHINS, Watson was able to enroll there at the age of 15, earning a B.S. in Zoology in 1947. He was attracted to the work of Salvador Luria, who eventually shared a Nobel Prize with Max Delbrück for their work on the nature of genetic mutations. In 1948, Watson began research in Luria’s laboratory and he received his Ph.D. in Zoology at Indiana University in 1950 at age 22. In 1951, the chemist Linus Pauling published his model of the protein alpha helix, find- ings that grew out of Pauling’s relentless efforts in X-ray crystallography and molecu- lar model building. Watson now wanted to learn to perform X-ray diffraction experi- ments so that he could work to determine the structure of DNA. Watson and Francis Crick proceeded to deduce the double helix structure of DNA, which they submitted to the journal Nature and was subsequently published on April 25, 1953. Watson subsequently presented a paper on the double helical structure of DNA at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Viruses in early June 1953. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

A Short History of DNA Technology 1865 - Gregor Mendel the Father of Genetics

A Short History of DNA Technology 1865 - Gregor Mendel The Father of Genetics The Augustinian monastery in old Brno, Moravia 1865 - Gregor Mendel • Law of Segregation • Law of Independent Assortment • Law of Dominance 1865 1915 - T.H. Morgan Genetics of Drosophila • Short generation time • Easy to maintain • Only 4 pairs of chromosomes 1865 1915 - T.H. Morgan •Genes located on chromosomes •Sex-linked inheritance wild type mutant •Gene linkage 0 •Recombination long aristae short aristae •Genetic mapping gray black body 48.5 body (cross-over maps) 57.5 red eyes cinnabar eyes 67.0 normal wings vestigial wings 104.5 red eyes brown eyes 1865 1928 - Frederick Griffith “Rough” colonies “Smooth” colonies Transformation of Streptococcus pneumoniae Living Living Heat killed Heat killed S cells mixed S cells R cells S cells with living R cells capsule Living S cells in blood Bacterial sample from dead mouse Strain Injection Results 1865 Beadle & Tatum - 1941 One Gene - One Enzyme Hypothesis Neurospora crassa Ascus Ascospores placed X-rays Fruiting on complete body medium All grow Minimal + amino acids No growth Minimal Minimal + vitamins in mutants Fragments placed on minimal medium Minimal plus: Mutant deficient in enzyme that synthesizes arginine Cys Glu Arg Lys His 1865 Beadle & Tatum - 1941 Gene A Gene B Gene C Minimal Medium + Citruline + Arginine + Ornithine Wild type PrecursorEnz A OrnithineEnz B CitrulineEnz C Arginine Metabolic block Class I Precursor OrnithineEnz B CitrulineEnz C Arginine Mutants Class II Mutants PrecursorEnz A Ornithine -

DNA: the Timeline and Evidence of Discovery

1/19/2017 DNA: The Timeline and Evidence of Discovery Interactive Click and Learn (Ann Brokaw Rocky River High School) Introduction For almost a century, many scientists paved the way to the ultimate discovery of DNA and its double helix structure. Without the work of these pioneering scientists, Watson and Crick may never have made their ground-breaking double helix model, published in 1953. The knowledge of how genetic material is stored and copied in this molecule gave rise to a new way of looking at and manipulating biological processes, called molecular biology. The breakthrough changed the face of biology and our lives forever. Watch The Double Helix short film (approximately 15 minutes) – hyperlinked here. 1 1/19/2017 1865 The Garden Pea 1865 The Garden Pea In 1865, Gregor Mendel established the foundation of genetics by unraveling the basic principles of heredity, though his work would not be recognized as “revolutionary” until after his death. By studying the common garden pea plant, Mendel demonstrated the inheritance of “discrete units” and introduced the idea that the inheritance of these units from generation to generation follows particular patterns. These patterns are now referred to as the “Laws of Mendelian Inheritance.” 2 1/19/2017 1869 The Isolation of “Nuclein” 1869 Isolated Nuclein Friedrich Miescher, a Swiss researcher, noticed an unknown precipitate in his work with white blood cells. Upon isolating the material, he noted that it resisted protein-digesting enzymes. Why is it important that the material was not digested by the enzymes? Further work led him to the discovery that the substance contained carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and large amounts of phosphorus with no sulfur. -

Genes, Genomes and Genetic Analysis

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION UNIT 1 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FORDefining SALE OR DISTRIBUTION and WorkingNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION with Genes © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Chapter 1 Genes, Genomes, and Genetic Analysis Chapter 2 DNA Structure and Genetic Variation © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Molekuul/Science Photo Library/Getty Images. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 9781284136609_CH01_Hartl.indd 1 08/11/17 8:50 am © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC -

![Max Ludwig Henning Delbruck (1906–1981) [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0999/max-ludwig-henning-delbruck-1906-1981-1-560999.webp)

Max Ludwig Henning Delbruck (1906–1981) [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Max Ludwig Henning Delbruck (1906–1981) [1] By: Hernandez, Victoria Max Ludwig Henning Delbrück applied his knowledge of theoretical physics to biological systems such as bacterial viruses called bacteriophages, or phages, and gene replication during the twentieth century in Germany and the US. Delbrück demonstrated that bacteria undergo random genetic mutations to resist phage infections. Those findings linked bacterial genetics to the genetics of higher organisms. In the mid-twentieth century, Delbrück helped start the Phage Group and Phage Course in the US, which further organized phage research. Delbrück also contributed to the DNA replication debate that culminated in the 1958 Meselson-Stahl experiment, which demonstrated how organisms replicate their genetic information. For his work with phages, Delbrück earned part of the 1969 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. Delbrück's work helped shape and establish new fields in molecular biology and genetics to investigate the laws of inheritance and development. Delbrück was born on 4 September 1906, as the last of seven children of Lina and Hans Delbrück, in Berlin, Germany. Delbrück grew up in Grunewald, a suburb of Berlin. In 1914, World War I [2] began. During the war, Delbrück's family struggled with food shortages and in 1917 Delbrück's oldest brother died in combat. After the war ended in 1918, Delbrück began to study astronomy. Some nights, Delbrück woke up in the middle of the night to observe the stars with his telescope. He also read about the seventeenth-century astronomer Johannes Kepler, who studied planetary motion in late sixteenth and early seventeenth century Germany. -

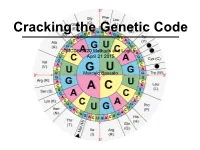

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

Happy Birthday to Renato Dulbecco, Cancer Researcher Extraordinaire

pbs.org http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/happy-birthday-renato-dulbecco-cancer-researcher-extraordinaire/ Happy birthday to Renato Dulbecco, cancer researcher extraordinaire Photo of Renato Dulbecco (public domain) Every elementary school student knows that Feb. 22 is George Washington’s birthday. Far fewer (if any) know that it is also the birthday of the Nobel Prize-winning scientist Renato Dulbecco. While not the father of his country — he was born in Italy and immigrated to the United States in 1947 — Renato Dulbecco is credited with playing a crucial role in our understanding of oncoviruses, a class of viruses that cause cancer when they infect animal cells. Dulbecco was born in Catanzaro, the capital of the Calabria region of Italy. Early in his childhood, after his father was drafted into the army during World War I, his family moved to northern Italy (first Cuneo, then Turin, and thence to Liguria). A bright boy, young Renato whizzed through high school and graduated in 1930 at the age of 16. From there, he attended the University of Turin, where he studied mathematics, physics, and ultimately medicine. Dulbecco found biology far more fascinating than the actual practice of medicine. As a result, he studied under the famed anatomist, Giuseppe Levi, and graduated at age 22 in 1936 at the top of his class with a degree in morbid anatomy and pathology (in essence, the study of disease). Soon after receiving his diploma, Dr. Dulbecco was inducted into the Italian army as a medical officer. Although he completed his military tour of duty by 1938, he was called back in 1940 when Italy entered World War II. -

Renato Dulbecco

BIOLOGIE ET HISTOIRE Renato Dulbecco Renato Dulbecco : de la virologie à la cancérologie F.N.R. RENAUD 1 résumé Né en Italie, Renato Dulbecco fait de brillantes études médicales mais est plus intéressé par la recherche en biologie que par la pratique médicale. Accueilli par Giuseppe Levi, il apprend l’histologie et la culture cellulaire avant de rejoindre le laboratoire de S.E. Luria puis celui de M. Delbrück pour travailler sur les systèmes bactéries-bactériophages puis sur la relation cellules-virus. Il met au point la méthode des plages de lyse virales sur des cultures cellulaires. Il est aussi à l’origine de la virologie tumorale moléculaire. D. Baltimore, HM Temin et lui-même sont récompensés par le prix Nobel de médecine et physiologie en 1975 pour leurs travaux sur l'interaction entre les virus tumoraux et le matériel génétique du matériel cellulaire. Très tourné vers les aspects pratiques et expérimentaux de la recherche, il est resté le plus long - temps possible à la paillasse et a initié un très grand nombre de jeunes chercheurs. mots-clés : culture cellulaire, virologie tumorale, plages de lyse, bactériophages. I. - LA JEUNESSE DE RENATO DULBECCO C'est à Catanzaro, capitale régionale de la Calabre en Italie, que naît Renato Dulbecco le 22 février 1914. Sa mère est Calabraise et son père Ligurien. Il ne reste que très peu de temps dans le sud de l’Italie, car son père est mobilisé et sa famille doit déménager dans le nord à Cuneo, puis à Turin. À la fin de la guerre, la famille Dulbeco s'ins - talle à Imperia en Ligurie. -

Biology: Exploring Life Resource

Name _______________________________ Class __________________ Date_______________ CHAPTER 11 DNA and the Language of Life Online Activity Worksheet 11.1 Genes are made of DNA. Experiment with bacteriophages. OBJECTIVE: to examine bacteriophage structure and life cycle and model the Hershey-Chase experiment In 1952, scientists were still debating the chemical nature of the gene. Was genetic information carried in molecules of protein or DNA? Two scientists, Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase, devised a simple, yet brilliant, experiment to answer this question. In this activity, you will model their experiment. • Examine the structure of the bacteriophage (also called a phage). Note that the phage is composed of only two types of molecules: protein and DNA. Click on the phage to begin. • The genetic material injected by the phage directs the bacterium to make new copies of the phage. Hershey and Chase knew the genetic material had to be either protein or DNA. Which one was it? Click next to reproduce the experiment they used to answer this question. • Hershey and Chase labeled two batches of phages with radioactive isotopes. Roll over each of the test tubes to see how the phages are labeled. Click next to continue. • The phages are added to flasks containing bacteria. Roll over the lower part of each flask to see the contents. Then click next to continue. • Click on a flask to begin. Then follow the instructions in the yellow notes. • Click on a test tube to start. Then follow the instructions in the yellow notes. • Click and drag the probe of the radiation detector over the test tubes to determine where the radioactivity is.