Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis Or Dissertation As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Jewish Life Contact

CONTACT WINTER 2004/SHEVAT 5764 VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 THE JOURNAL OF JEWISH LIFE NETWORK/STEINHARDT FOUNDATION Marketing Jewish Life contact WINTER 2004/SHEVAT 5764 VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 Marketing Jewish Life Eli Valley Editor or the past dozen years, many American Jewish institutions have tai- Erica Coleman Copy Editor lored programming towards that elusive yet abundant breed: the unaf- Janet Mann filiated Jew. Millions have been spent on new programs that promise to Administration F reach Jews who lie outside the community’s orbit. Unfortunately, we Yakov Wisniewski have often neglected perhaps the most crucial area of focus: innovative mar- Design Director keting of programs and offerings. Instead, many of us have relied on perfunc- tory marketing plans that place the message of outreach and engagement in JEWISH LIFE NETWORK STEINHARDT FOUNDATION the media of the already-affiliated. Michael H. Steinhardt Chairman Such logic is counter-intuitive. If our target is the unengaged, then by defini- Rabbi Irving Greenberg tion they exist outside the range of Jewish media. The competition for their President attention is fierce. Like everyone else, Jews in the open society are subject to Rabbi David Gedzelman seemingly limitless avenues of identity exploration and a whirlwind of infor- Executive Director mation. The deluge of messages and options is equivalent to spam – unless it Jonathan J. Greenberg z”l Founding Director is found to be immediately compelling, it will be deleted. In such an atmos- phere, strategic message creation and placement is crucial for the success and CONTACT is produced and distributed by Jewish Life Network/ vitality of Jewish programs. -

Noahidism Or B'nai Noah—Sons of Noah—Refers To, Arguably, a Family

Noahidism or B’nai Noah—sons of Noah—refers to, arguably, a family of watered–down versions of Orthodox Judaism. A majority of Orthodox Jews, and most members of the broad spectrum of Jewish movements overall, do not proselytize or, borrowing Christian terminology, “evangelize” or “witness.” In the U.S., an even larger number of Jews, as with this writer’s own family of orientation or origin, never affiliated with any Jewish movement. Noahidism may have given some groups of Orthodox Jews a method, arguably an excuse, to bypass the custom of nonconversion. Those Orthodox Jews are, in any event, simply breaking with convention, not with a scriptural ordinance. Although Noahidism is based ,MP3], Tạləmūḏ]תַּלְמּוד ,upon the Talmud (Hebrew “instruction”), not the Bible, the text itself does not explicitly call for a Noahidism per se. Numerous commandments supposedly mandated for the sons of Noah or heathen are considered within the context of a rabbinical conversation. Two only partially overlapping enumerations of seven “precepts” are provided. Furthermore, additional precepts, not incorporated into either list, are mentioned. The frequently referenced “seven laws of the sons of Noah” are, therefore, misleading and, indeed, arithmetically incorrect. By my count, precisely a dozen are specified. Although I, honestly, fail to understand why individuals would self–identify with a faith which labels them as “heathen,” that is their business, not mine. The translations will follow a series of quotations pertinent to this monotheistic and ,MP3], tạləmūḏiy]תַּלְמּודִ י ,talmudic (Hebrew “instructive”) new religious movement (NRM). Indeed, the first passage quoted below was excerpted from the translated source text for Noahidism: Our Rabbis taught: [Any man that curseth his God, shall bear his sin. -

USY's Scooby Jew Convention

April 2015 5775 USY’s Scooby Jew Convention In This Issue: By Mayer Adelberg On February 20, 2015, over one hundred teens converged on the Flamingo From the Rabbi Resort and Spa in Santa Rosa, California. It was a weekend of Jewish Page 3 learning, ruah (spirit) and fun, and the theme for this fantastic convention was, none other than, Scooby Doo. The three-day convention, called ISS (Intensive Study Seminar), was the first convention of the year where eighth graders were invited. Although President’s they were part of their own semi-separate convention (8th Grade Shabba- Perspective ton), they still intermingled with the USYers for some programs and for Page 5 meals. ISS was a weekend of Judaism and Jewish learning. As Calendar a youth group Pages 14 & 15 which is part of the Conservative movement, New Frontier USY incorporates prayer April experiences into Birthdays our conventions; Page 21 for ISS these were held in transformed hotel rooms. April The approach was Anniversaries interactive and Page 22 non-traditional, while the fundamental elements of the services were kept intact. Programming is a major part of ISS. With programs that cover Judaism as well as programs that completely relate to USYers’ lives, it is an important 100% club element that takes planning and serious consideration. At ISS, we had programs such as Israeli Capture the Flag, Pe’ah it Forward (discussing Pages 23 & 24 Sh’mittah), Parsha Palooza, and Jewpardy (Jewish Jeopardy.) “ISS was an incredible experience where I got to meet people who other- contributions wise I wouldn’t have even known existed,” says Danielle Horovitz, an 8th Pages 25 & 26 grader in Saratoga USY attending her first convention. -

Jewish Subcultures Online: Outreach, Dating, and Marginalized Communities ______

JEWISH SUBCULTURES ONLINE: OUTREACH, DATING, AND MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies ____________________________________ By Rachel Sara Schiff Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Leila Zenderland, Chair Professor Terri Snyder, Department of American Studies Professor Carrie Lane, Department of American Studies Spring, 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Jewish individuals use and create communities online to enrich their Jewish identity. The Internet provides Jews who do not fit within their brick and mortar communities an outlet that gives them voice, power, and sometimes anonymity. They use these websites to balance their Jewish identities and other personal identities that may or may not fit within their local Jewish community. This research was conducted through analyzing a broad range of websites. The first chapter, the introduction, describes the Jewish American population as a whole as well as the history of the Internet. The second chapter, entitled “The Black Hats of the Internet,” discusses how the Orthodox community has used the Internet to create a modern approach to outreach. It focuses in particular on the extensive web materials created by Chabad and Aish Hatorah, which offer surprisingly modern twists on traditional texts. The third chapter is about Jewish online dating. It uses JDate and other secular websites to analyze how Jewish singles are using the Internet. This chapter also suggests that the use of the Internet may have an impact on reducing interfaith marriage. The fourth chapter examines marginalized communities, focusing on the following: Jewrotica; the Jewish LGBT community including those who are “OLGBT” (Orthodox LGBT); Punk Jews; and feminist Jews. -

OF AISH HA TORAH: BA 'ALE! TESHUVA R and the NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENT PHENOMENON Aaron Joshua Tapper

jJJEWIT§IHI jJ(Q)U~NAIL (Q)JF 1 0 ~ " ' Q" ,,J ' : 0 i ''' VOLUME XLIV NUi'dBERS 1 and 2 2002 ' ,j'' 0 ~ CONTENTS ';" ,p' The 'Cult' of Aish Hatorah: Ba'alei Tes!tuva and the New Religious lVIovement Phenomenon AARON JOSHUA TAPPER Fieldwork Among the 'Ultra-Orthodox': The Insider Outsider Paradigm Revisited LISA R. KAUL-SEIDMAN Outremont's Hassidim and Their Neighbours: An Eruv and its Repercussions WILLIAM SHAFFIR .Jewish Rdi.1gees in Britain and in New York HILARY L. RUBINSTEIN The.Jewish Economic Man HAROLD POLLINS :;. The .Jews of Britain, 16.)6-2ooo i ,D \VlLLIAl\1 D. RUBINSTEIN ~ ~ ' • .,., Book Reviews Chronicle i <I' J1 ...J' Editor: .Judith Freedman Jli I \ I OBJECTS AND SPONSORSHIP OF i THE JEWISH JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY I 7he Jewish Journal'!! Sociology was sponsored by the Cultural Department of the 1 World Jewish Congress from its inception in 1959 until the end of 1980. Thereafter, from the first issue of 1981 (volume 23, no. r), the Journal has been sponsored by Maurice Freedman Research Trust Limited, which is rcgisten:U as an educational charity by the Charity Commission of England and Wales (no. 326077). It has as its main purpose the encouragement of research in the sociology of the Jews and the publication of The Jewish Journal or Sociology. The objects of the Journal remain as stated in the Editorial of the first issue in '959: 'This journal has been brought into being in order to provide an international vehicle for serious writing on Jewish social affairs . .. Academically we address ourselves not only to sociologists, but to social scientists in general, to historians, to philosophers, and to students of comparative religion . -

High Holy Days 2021 / 5782 Emanu-El B'bayit Youth and Family

Emanu-El SF CHRONICLE NO. 40 | AUGUST 2021 | ELUL Youth and Family High Holy Days Emanu-El Education 2021 / 5782 B’Bayit PAGES 4 – 7 PAGE 8 Registration PAGE 9 TITLE Opening the Gates High Holy Days 2021 / 5782 2 AUGUST 2021 hhd.emanuelsf.org Shalom Rav from our Rabbi By Richard and Rhoda Goldman Senior Rabbi Beth Singer Monday, August 9th, is the first day s I love to remind you, we often pen these messages of the Hebrew month of Elul. This Aone to two months in advance of publication and, as month is designated for spiritual you already know, post-pandemic, our reality changes preparation for the High Holy Days slowly and quickly at the same time. Are you still feeling ahead. There are countless ways for the lingering effects of shelter-in-place? Have you been to you to engage and renew. Here are the theater? Ball game? Services in the Main? Some in our just a few to consider: Each Friday community leapt back into activities as fast as the rules in Elul for the entire month, starting allowed, while others continue to practice great caution or Friday, August 13th, we use a special have even decided that Home is Best! prayer book with beautiful readings at our One Shabbat 6:00 pm service. As I reflect on this past year, which was “more different” Join us. Spend more time in nature than any other year of my previous 32 years in the Richard and Rhoda Goldman throughout Elul. Engage in acts Senior Rabbi Beth Singer rabbinate, the thing that strikes me is how Jewish rituals of tzedakah. -

Erev Shabbat Service 2.0.Dwd

zay zlaw WELCOMING SHABBAT Congregation Beth Am mr zia zlidw .dg¨Epn§ zA¨W© ,dg¨n§ U¦ e§ dx¨F` l`¥x¨U§ i¦§l df¤ mFi This is our day of light and rejoicing, Sabbath peace, Sabbath rest. - 0 - CONTENTS Meditations before prayer............................................. 3 Opening songs.......................................................... 5 Meditations for Shabbat.............................................. 7 Candle lighting........................................................... 9 Kiddush..................................................................... 11 Blessing for Children................................................... 12 Barchu (Call to Worship)............................................. 18 Sh’ma........................................................................ 22 Amidah..................................................................... 31 English readings following Amidah.............................. 37 Mishebeirach for Healing............................................ 42, 57 Aleinu....................................................................... 45 Readings before Kaddish........................................... 46 Kaddish.................................................................... 52 Additional Songs........................................................ 55 Additional Readings and Meditations........................... 59 - 1 - About This Prayerbook At Beth Am our goal is to create joyous, participatory worship that engages the intellect and deepens Jewish learning; that touches -

Chabad- Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere Sharrona Pearla a University of Pennsylvania Published Online: 09 Sep 2014

This article was downloaded by: [University of Pennsylvania] On: 11 September 2014, At: 10:53 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Media and Religion Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hjmr20 Exceptions to the Rule: Chabad- Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere Sharrona Pearla a University of Pennsylvania Published online: 09 Sep 2014. To cite this article: Sharrona Pearl (2014) Exceptions to the Rule: Chabad-Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere, Journal of Media and Religion, 13:3, 123-137 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15348423.2014.938973 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

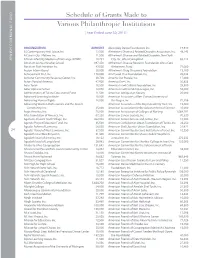

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

The Yomim Nora'im, Days of Awe Or High Holy Days, Are Among

The Yomim Nora’im, Days of Awe or High Holy Days, are among the most sacred times in the Jewish calendar. The period from Rosh HaShanah through Yom Kippur encompasses a time for reflection and renewal for Jews, both as individuals and as a community. In addition, throughout the world, and especially in American Jewish life, more Jews will attend services during these days than any other time of the year. The High Holy Days fall at a particularly important time for Jewish students on college campuses. Coming at the beginning of the academic year, they will often be a new student’s first introduction to the Jewish community on campus. Those students who have a positive experience are likely to consider attending another event or service, while those who do not feel comfortable or welcomed will likely not return again. Therefore, it is critical that both services and other events around the holidays be planned with a great deal of care and forethought. This packet is designed as a “how-to” guide for creating a positive, Reform High Holy Day experience on campus. It includes service outlines, program suggestions and materials, and sample text studies for leaders and participants. There are materials and suggestions for campuses of many varieties, including those which have separate Reform services – either led solely or in part by students – and those which only have one “communal” service. The program ideas include ways to help get people involved in the Jewish community during this time period whether or not they stay on campus for the holidays. -

De-Constructing the Outreach-Inreach Debate Prof

4 JERUSALEM PAPERS ON JEWISH CONTINUITY AN OPEN FORUM ON EDUCATIONAL POLICY AND h PRACTICE De-Constructing the Outreach-Inreach Debate Prof. Steven Cohen November 1996 The Melton Centre for Jewish Education The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus, Jerusalem 91905 Israel De-Constructing the Outreach-Inreach Debate Steven M. Cohen The Melton Centre for Jewish Education The Hebrew University in Jerusalem As is widely recognized, the concern for Jewish continuity has stood at the top of the organized Jewish community's agenda, at least for the last five years or so. Quite naturally, the issue has provoked a number of key strategic debates. One of the earliest was between what may be called "associationists" and "educationists." Another divides the education ists into two camps: the advocates of "near-inreach," and the proponents of'Tar-outreach" (Cohen 1993). With regard to the first debate, by associationists I refer to those who believe the main goal of what have been called "Jewish continuity" programs is to increase opportunities for Jewish association, to bring Jews together, especially single young adult Jews. The principal aim here is to encourage them to engage in romance, marriage, and parenting. In con trast, Jewish educators, rabbis, enlightened lay leaders and communal professionals (as well as their high-paid social science consultants) have argued for a different approach. They contend that Jewish continuity de mands Jewish content, that association is only a necessary, but not a suffi cient, step to promoting a higher quality of Jewish life. For them, Jewish education - in some form, if not in all its forms - is the sine qua non of the Jewish continuity enterprise. -

Growing Outreach

The Coolest OutdoorOOu Furniture Store Blending Your Dreams With OurResidential Creativity & Commercial Licensed & Insured in Bloomfield Hills. & Call Us Today! 1751 S. Telegraph Rd. BRICK PAVING & LANDSCAPING CONSTRUCTION, INC. CONSTRUCTION Bloomfield Hills Construction | Remodeling | Renovation 248.230.1600 www.coastaloutdoorlivingspace.com $2.00 MAY 10-16, 2012 / 18-24 IYAR 5772 A JEWISH RENAISSANCE MEDIA PUBLICATION theJEWISHNEWS.com » Earthly Inspiration Israel’s unceasing magnetism begins with walking the land. See page 30. ▲ » A New World Local artist Robert Schefman’s paintings explore ever-changing technology. See page 43. » Lag b’Omer Bonfires Ex-Detroiter explains meaning behind holiday bonfires popular in Israel. See page 61. Collected Knowledge, 2012, DETROIT JEWISH NEWS Robert Schefman metro » cover story Brett Mountain Brett Brett Mountain Brett Rabbi Mendel Shemtov; Rabbi Bentzion Stein; Schneur Zalman Krinsky, Vilnius, Lithuania; Moshe Spalter, Costa Rica; Lavi Shemtov, West Bloomfield; Yudi Namdar, Gothenburg, Sweden; Shmuli Friedman, Bahia Blanca, Argentina; Moti Schusterman, Atlanta; Mendel Korf, Los Not Your Angeles; Mendel Marinovsky, Houston; Tzvi Alperovitch, Belmont, England; Rabbi Mendel Stein erhaps you’ve seen them. Mother’s Teenage boys in white P shirts, black pants and hats walking on Northwestern Highway Mikvah to visit business owners before Growing Shabbat, or manning a sukkah on Putting a modern twist wheels in an Orchard Lake parking Outreach lot or driving in a parade of cars on an ancient tradition. topped with hand-built Chanukah menorahs. Rabbi Marla Hornsten at the Temple Israel mikvah They are the middle school Lubavitch Yeshiva Eduational Center’s and high school students of the Ronelle Grier | Contributing Writer expanded new home almost ready.