De-Constructing the Outreach-Inreach Debate Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Jewish Life Contact

CONTACT WINTER 2004/SHEVAT 5764 VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 THE JOURNAL OF JEWISH LIFE NETWORK/STEINHARDT FOUNDATION Marketing Jewish Life contact WINTER 2004/SHEVAT 5764 VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 Marketing Jewish Life Eli Valley Editor or the past dozen years, many American Jewish institutions have tai- Erica Coleman Copy Editor lored programming towards that elusive yet abundant breed: the unaf- Janet Mann filiated Jew. Millions have been spent on new programs that promise to Administration F reach Jews who lie outside the community’s orbit. Unfortunately, we Yakov Wisniewski have often neglected perhaps the most crucial area of focus: innovative mar- Design Director keting of programs and offerings. Instead, many of us have relied on perfunc- tory marketing plans that place the message of outreach and engagement in JEWISH LIFE NETWORK STEINHARDT FOUNDATION the media of the already-affiliated. Michael H. Steinhardt Chairman Such logic is counter-intuitive. If our target is the unengaged, then by defini- Rabbi Irving Greenberg tion they exist outside the range of Jewish media. The competition for their President attention is fierce. Like everyone else, Jews in the open society are subject to Rabbi David Gedzelman seemingly limitless avenues of identity exploration and a whirlwind of infor- Executive Director mation. The deluge of messages and options is equivalent to spam – unless it Jonathan J. Greenberg z”l Founding Director is found to be immediately compelling, it will be deleted. In such an atmos- phere, strategic message creation and placement is crucial for the success and CONTACT is produced and distributed by Jewish Life Network/ vitality of Jewish programs. -

Noahidism Or B'nai Noah—Sons of Noah—Refers To, Arguably, a Family

Noahidism or B’nai Noah—sons of Noah—refers to, arguably, a family of watered–down versions of Orthodox Judaism. A majority of Orthodox Jews, and most members of the broad spectrum of Jewish movements overall, do not proselytize or, borrowing Christian terminology, “evangelize” or “witness.” In the U.S., an even larger number of Jews, as with this writer’s own family of orientation or origin, never affiliated with any Jewish movement. Noahidism may have given some groups of Orthodox Jews a method, arguably an excuse, to bypass the custom of nonconversion. Those Orthodox Jews are, in any event, simply breaking with convention, not with a scriptural ordinance. Although Noahidism is based ,MP3], Tạləmūḏ]תַּלְמּוד ,upon the Talmud (Hebrew “instruction”), not the Bible, the text itself does not explicitly call for a Noahidism per se. Numerous commandments supposedly mandated for the sons of Noah or heathen are considered within the context of a rabbinical conversation. Two only partially overlapping enumerations of seven “precepts” are provided. Furthermore, additional precepts, not incorporated into either list, are mentioned. The frequently referenced “seven laws of the sons of Noah” are, therefore, misleading and, indeed, arithmetically incorrect. By my count, precisely a dozen are specified. Although I, honestly, fail to understand why individuals would self–identify with a faith which labels them as “heathen,” that is their business, not mine. The translations will follow a series of quotations pertinent to this monotheistic and ,MP3], tạləmūḏiy]תַּלְמּודִ י ,talmudic (Hebrew “instructive”) new religious movement (NRM). Indeed, the first passage quoted below was excerpted from the translated source text for Noahidism: Our Rabbis taught: [Any man that curseth his God, shall bear his sin. -

Jewish Subcultures Online: Outreach, Dating, and Marginalized Communities ______

JEWISH SUBCULTURES ONLINE: OUTREACH, DATING, AND MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies ____________________________________ By Rachel Sara Schiff Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Leila Zenderland, Chair Professor Terri Snyder, Department of American Studies Professor Carrie Lane, Department of American Studies Spring, 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Jewish individuals use and create communities online to enrich their Jewish identity. The Internet provides Jews who do not fit within their brick and mortar communities an outlet that gives them voice, power, and sometimes anonymity. They use these websites to balance their Jewish identities and other personal identities that may or may not fit within their local Jewish community. This research was conducted through analyzing a broad range of websites. The first chapter, the introduction, describes the Jewish American population as a whole as well as the history of the Internet. The second chapter, entitled “The Black Hats of the Internet,” discusses how the Orthodox community has used the Internet to create a modern approach to outreach. It focuses in particular on the extensive web materials created by Chabad and Aish Hatorah, which offer surprisingly modern twists on traditional texts. The third chapter is about Jewish online dating. It uses JDate and other secular websites to analyze how Jewish singles are using the Internet. This chapter also suggests that the use of the Internet may have an impact on reducing interfaith marriage. The fourth chapter examines marginalized communities, focusing on the following: Jewrotica; the Jewish LGBT community including those who are “OLGBT” (Orthodox LGBT); Punk Jews; and feminist Jews. -

OF AISH HA TORAH: BA 'ALE! TESHUVA R and the NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENT PHENOMENON Aaron Joshua Tapper

jJJEWIT§IHI jJ(Q)U~NAIL (Q)JF 1 0 ~ " ' Q" ,,J ' : 0 i ''' VOLUME XLIV NUi'dBERS 1 and 2 2002 ' ,j'' 0 ~ CONTENTS ';" ,p' The 'Cult' of Aish Hatorah: Ba'alei Tes!tuva and the New Religious lVIovement Phenomenon AARON JOSHUA TAPPER Fieldwork Among the 'Ultra-Orthodox': The Insider Outsider Paradigm Revisited LISA R. KAUL-SEIDMAN Outremont's Hassidim and Their Neighbours: An Eruv and its Repercussions WILLIAM SHAFFIR .Jewish Rdi.1gees in Britain and in New York HILARY L. RUBINSTEIN The.Jewish Economic Man HAROLD POLLINS :;. The .Jews of Britain, 16.)6-2ooo i ,D \VlLLIAl\1 D. RUBINSTEIN ~ ~ ' • .,., Book Reviews Chronicle i <I' J1 ...J' Editor: .Judith Freedman Jli I \ I OBJECTS AND SPONSORSHIP OF i THE JEWISH JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY I 7he Jewish Journal'!! Sociology was sponsored by the Cultural Department of the 1 World Jewish Congress from its inception in 1959 until the end of 1980. Thereafter, from the first issue of 1981 (volume 23, no. r), the Journal has been sponsored by Maurice Freedman Research Trust Limited, which is rcgisten:U as an educational charity by the Charity Commission of England and Wales (no. 326077). It has as its main purpose the encouragement of research in the sociology of the Jews and the publication of The Jewish Journal or Sociology. The objects of the Journal remain as stated in the Editorial of the first issue in '959: 'This journal has been brought into being in order to provide an international vehicle for serious writing on Jewish social affairs . .. Academically we address ourselves not only to sociologists, but to social scientists in general, to historians, to philosophers, and to students of comparative religion . -

Chabad- Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere Sharrona Pearla a University of Pennsylvania Published Online: 09 Sep 2014

This article was downloaded by: [University of Pennsylvania] On: 11 September 2014, At: 10:53 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Media and Religion Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hjmr20 Exceptions to the Rule: Chabad- Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere Sharrona Pearla a University of Pennsylvania Published online: 09 Sep 2014. To cite this article: Sharrona Pearl (2014) Exceptions to the Rule: Chabad-Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere, Journal of Media and Religion, 13:3, 123-137 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15348423.2014.938973 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

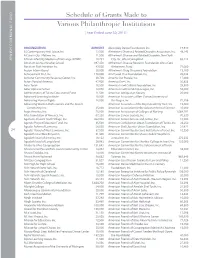

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

Growing Outreach

The Coolest OutdoorOOu Furniture Store Blending Your Dreams With OurResidential Creativity & Commercial Licensed & Insured in Bloomfield Hills. & Call Us Today! 1751 S. Telegraph Rd. BRICK PAVING & LANDSCAPING CONSTRUCTION, INC. CONSTRUCTION Bloomfield Hills Construction | Remodeling | Renovation 248.230.1600 www.coastaloutdoorlivingspace.com $2.00 MAY 10-16, 2012 / 18-24 IYAR 5772 A JEWISH RENAISSANCE MEDIA PUBLICATION theJEWISHNEWS.com » Earthly Inspiration Israel’s unceasing magnetism begins with walking the land. See page 30. ▲ » A New World Local artist Robert Schefman’s paintings explore ever-changing technology. See page 43. » Lag b’Omer Bonfires Ex-Detroiter explains meaning behind holiday bonfires popular in Israel. See page 61. Collected Knowledge, 2012, DETROIT JEWISH NEWS Robert Schefman metro » cover story Brett Mountain Brett Brett Mountain Brett Rabbi Mendel Shemtov; Rabbi Bentzion Stein; Schneur Zalman Krinsky, Vilnius, Lithuania; Moshe Spalter, Costa Rica; Lavi Shemtov, West Bloomfield; Yudi Namdar, Gothenburg, Sweden; Shmuli Friedman, Bahia Blanca, Argentina; Moti Schusterman, Atlanta; Mendel Korf, Los Not Your Angeles; Mendel Marinovsky, Houston; Tzvi Alperovitch, Belmont, England; Rabbi Mendel Stein erhaps you’ve seen them. Mother’s Teenage boys in white P shirts, black pants and hats walking on Northwestern Highway Mikvah to visit business owners before Growing Shabbat, or manning a sukkah on Putting a modern twist wheels in an Orchard Lake parking Outreach lot or driving in a parade of cars on an ancient tradition. topped with hand-built Chanukah menorahs. Rabbi Marla Hornsten at the Temple Israel mikvah They are the middle school Lubavitch Yeshiva Eduational Center’s and high school students of the Ronelle Grier | Contributing Writer expanded new home almost ready. -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis Or Dissertation As A

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ______________ Jennifer Thompson Date Continuity Through Transformation: American Jews, Judaism, and Intermarriage By Jennifer Thompson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Division of Religion Ethics and Society _____________________________________________________ Don Seeman, Ph.D. Advisor _____________________________________________________ Eric Goldstein, Ph.D. Committee Member _____________________________________________________ Gary Laderman, Ph.D. Committee Member _____________________________________________________ Bradd Shore, Ph.D. Committee Member _____________________________________________________ Steven M. Tipton, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: _____________________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies -

Choosing Jewish Fr Bk Cov 4/6/06 12:32 PM Page 1

Choosing Jewish fr bk cov 4/6/06 12:32 PM Page 1 CHOOSING JEWISH Conversations About SYLVIA BARACK FISHMAN Conversion Sylvia Barack Fishman American Jewish Committee The Jacob Blaustein Building 165 East 56 Street New York, NY 10022 The American Jewish Committee publishes in these areas: •Hatred and Anti-Semitism •Pluralism •Israel •American Jewish Life •International Jewish Life •Human Rights www.ajc.org April 2006 $5.00 AJC AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE CHOOSING JEWISH Conversations about Conversion Sylvia Barack Fishman The American Jewish Committee protects the rights and freedoms of Jews the world over; combats bigotry and anti- Semitism and promotes human rights for all; works for the security of Israel and deepened understanding between Americans and Israelis; advocates public policy positions rooted in American democratic values and the perspectives of the Jewish heritage; and enhances the creative vitality of the Jewish people. Founded in 1906, it is the pioneer human-relations agency in the United States. american jewish committee Contents Sylvia Barack Fishman is professor of Contemporary Jewish Life in Foreword v the Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Department at Brandeis Univer- Acknowledgments 1 sity and codirector of the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. The present work, Choosing Jewish: Conversations about Conversion, carries forward Choosing Jewish: the discussion begun in Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Conversations about Conversion Marriage (Brandeis University Press/University Press of New England, Introduction: Conversion Is Controversial 2004). in Contemporary Jewish Life 3 Why Study Conversion into Judaism? 3 Publication of this study was made possible in part by funds from the William Petschek National Jewish Family Center. -

Jewish Community Study of New York 2011

JEWISH COMMUNITY STUDY OF NEW YORK: 2011 COMPREHENSIVE REPORT BRONX BROOKLYN MANHATTAN QUEENS STATEN ISLAND NASSAU SUFFOLK WESTCHESTER UJA-Federation of New York Leadership President Special Advisor to the Jewish Community Study of Jerry W. Levin* President New York: 2011 Committee Michael G. Jesselson Chair of the Board Chair Alisa R. Doctoroff* Senior Vice President, Scott A. Shay Financial Resource Executive Vice President & CEO Development Laurie Blitzer John S. Ruskay Mark D. Medin Beth Finger Aileen Gitelson Chair, Caring Commission Senior Vice President, Billie Gold Jeffrey A. Schoenfeld* Strategic Planning and Cindy Golub Organizational Resources Judah Gribetz Chair, Commission on Jewish Alisa Rubin Kurshan John A. Herrmann Identity and Renewal Vivien Hidary Eric S. Goldstein* Senior Vice President, Edward M. Kerschner Agency Relations Meyer Koplow Chair, Commission on the Roberta Marcus Leiner Alisa Rubin Kurshan Jewish People Sara Nathan Alisa F. Levin* Chief Financial Officer Leonard Petlakh Irvin A. Rosenthal Karen Radkowsky Chair, Jewish Communal William E. Rapfogel Network Commission General Counsel, Chief Rabbi Peter Rubinstein Helen Samuels* Compliance Officer & Daniel Septimus Secretary David Silvers General Chair, 2012 Campaign Ellen R. Zimmerman Tara Slone Marcia Riklis* Nicki Tanner Managing Director, Marketing Julia E. Zeuner Campaign Chairs and Communications Karen S.W. Friedman* Leslie K. Lichter Director of Research and Wayne K. Goldstein* Study Director William L. Mack Executive Vice Presidents Jennifer Rosenberg Emeriti Treasurer Ernest W. Michel Executive Director, Educational Roger W. Einiger* Stephen D. Solender Resources and Organizational Development and Study Executive Committee At Large *Executive Committee member Supervisor Lawrence C. Gottlieb* Lyn Light Geller Linda Mirels* Jeffrey M. -

Jewish Outreach in Those Days and in Our Times

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • YU Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld • December 2019 • Kislev 5780 בימים ההם בזמן הזה Jewish Outreach in those Days and in our times Dedicated by Dr. David and Barbara Hurwitz in honor of their children and grandchildren We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Cong. Ohr HaTorah Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Atlanta, GA Lawrence-Cedarhurst Cedarhurst, NY Beth Jacob Congregation Cong. Shaarei Tefillah Beverly Hills, CA Newton Centre, MA Young Israel of New Hyde Park Beth Jacob Congregation Green Road Synagogue New Hyde Park, NY Oakland, CA Beachwood, OH Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek The Jewish Center Philadelphia, PA New York, NY New Rochelle New Rochelle, NY Boca Raton Synagogue Jewish Center of Young Israel of Boca Raton, FL Brighton Beach Brooklyn, NY Scarsdale Cong. Ahavas Achim Scarsdale, NY Highland Park, NJ Koenig Family Young Israel of Foundation Cong. Ahavath Torah Brooklyn, NY West Hartford Englewood, NJ West Hartford, CT Yeshivat Reishit Cong. Beth Sholom Beit Shemesh/Jerusalem Young Israel of Lawrence, NY Israel West Hempstead Cong. Beth Sholom West Hempstead, NY Young Israel of Providence, RI Century City Young Israel of Cong. Bnai Yeshurun Los Angeles, CA Woodmere Teaneck, NJ Woodmere, NY Young Israel of Cong. Ohab Zedek Hollywood Ft Lauderdale New York, NY Hollywood, FL Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman, President, Yeshiva -

2020 JCF Giving Report

Jewish Communal Fund GIVING 2020 REPORT ABOUT JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND Jewish Communal Fund (JCF) is the largest and most active network of Jewish funders in the nation. JCF facilitates philanthropy for more than 8,000 people associated with 4,100 funds, totaling $2 billion in charitable assets. In FY 2020, our generous Fundholders granted out $536 million—27% of our assets—to charities in all sectors. The impact of JCF’s network of funders on the Jewish community and beyond is profound. In addition to an annual unrestricted grant to UJA-Federation of New York, JCF’s Special Gifts Fund (our endowment) has granted more than $20 million since 1999 to support programs in the Jewish community at home and abroad, including kosher food pantries and soup kitchens, day camp scholarships for children from low-income homes, and programs for Holocaust survivors with dementia. These charities are selected with the assistance of UJA-Federation of NY. For a simpler, easier, smarter way to give, look no further than the Jewish Communal Fund. To learn more about JCF, visit jcfny.org or call us at (212) 752-8277. INTRODUCTION TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Letter from the President and CEO 2 Introduction 3–6 The JCF Philanthropic Community 7–15 Grants 16 Contributions 17–28 Grants Listing 2 www.jcfny.org • 212-752-8277 Letter from the President and CEO JCF’s extraordinarily generous Fundholders increased their giving to meet the tremendous needs that arose amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. In FY 2020, JCF Fundholders recommended more than 64,000 grants totaling a record-breaking $536 million to charities in every sector.