OF AISH HA TORAH: BA 'ALE! TESHUVA R and the NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENT PHENOMENON Aaron Joshua Tapper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Jewish Life Contact

CONTACT WINTER 2004/SHEVAT 5764 VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 THE JOURNAL OF JEWISH LIFE NETWORK/STEINHARDT FOUNDATION Marketing Jewish Life contact WINTER 2004/SHEVAT 5764 VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 Marketing Jewish Life Eli Valley Editor or the past dozen years, many American Jewish institutions have tai- Erica Coleman Copy Editor lored programming towards that elusive yet abundant breed: the unaf- Janet Mann filiated Jew. Millions have been spent on new programs that promise to Administration F reach Jews who lie outside the community’s orbit. Unfortunately, we Yakov Wisniewski have often neglected perhaps the most crucial area of focus: innovative mar- Design Director keting of programs and offerings. Instead, many of us have relied on perfunc- tory marketing plans that place the message of outreach and engagement in JEWISH LIFE NETWORK STEINHARDT FOUNDATION the media of the already-affiliated. Michael H. Steinhardt Chairman Such logic is counter-intuitive. If our target is the unengaged, then by defini- Rabbi Irving Greenberg tion they exist outside the range of Jewish media. The competition for their President attention is fierce. Like everyone else, Jews in the open society are subject to Rabbi David Gedzelman seemingly limitless avenues of identity exploration and a whirlwind of infor- Executive Director mation. The deluge of messages and options is equivalent to spam – unless it Jonathan J. Greenberg z”l Founding Director is found to be immediately compelling, it will be deleted. In such an atmos- phere, strategic message creation and placement is crucial for the success and CONTACT is produced and distributed by Jewish Life Network/ vitality of Jewish programs. -

Noahidism Or B'nai Noah—Sons of Noah—Refers To, Arguably, a Family

Noahidism or B’nai Noah—sons of Noah—refers to, arguably, a family of watered–down versions of Orthodox Judaism. A majority of Orthodox Jews, and most members of the broad spectrum of Jewish movements overall, do not proselytize or, borrowing Christian terminology, “evangelize” or “witness.” In the U.S., an even larger number of Jews, as with this writer’s own family of orientation or origin, never affiliated with any Jewish movement. Noahidism may have given some groups of Orthodox Jews a method, arguably an excuse, to bypass the custom of nonconversion. Those Orthodox Jews are, in any event, simply breaking with convention, not with a scriptural ordinance. Although Noahidism is based ,MP3], Tạləmūḏ]תַּלְמּוד ,upon the Talmud (Hebrew “instruction”), not the Bible, the text itself does not explicitly call for a Noahidism per se. Numerous commandments supposedly mandated for the sons of Noah or heathen are considered within the context of a rabbinical conversation. Two only partially overlapping enumerations of seven “precepts” are provided. Furthermore, additional precepts, not incorporated into either list, are mentioned. The frequently referenced “seven laws of the sons of Noah” are, therefore, misleading and, indeed, arithmetically incorrect. By my count, precisely a dozen are specified. Although I, honestly, fail to understand why individuals would self–identify with a faith which labels them as “heathen,” that is their business, not mine. The translations will follow a series of quotations pertinent to this monotheistic and ,MP3], tạləmūḏiy]תַּלְמּודִ י ,talmudic (Hebrew “instructive”) new religious movement (NRM). Indeed, the first passage quoted below was excerpted from the translated source text for Noahidism: Our Rabbis taught: [Any man that curseth his God, shall bear his sin. -

Jewish Subcultures Online: Outreach, Dating, and Marginalized Communities ______

JEWISH SUBCULTURES ONLINE: OUTREACH, DATING, AND MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies ____________________________________ By Rachel Sara Schiff Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Leila Zenderland, Chair Professor Terri Snyder, Department of American Studies Professor Carrie Lane, Department of American Studies Spring, 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Jewish individuals use and create communities online to enrich their Jewish identity. The Internet provides Jews who do not fit within their brick and mortar communities an outlet that gives them voice, power, and sometimes anonymity. They use these websites to balance their Jewish identities and other personal identities that may or may not fit within their local Jewish community. This research was conducted through analyzing a broad range of websites. The first chapter, the introduction, describes the Jewish American population as a whole as well as the history of the Internet. The second chapter, entitled “The Black Hats of the Internet,” discusses how the Orthodox community has used the Internet to create a modern approach to outreach. It focuses in particular on the extensive web materials created by Chabad and Aish Hatorah, which offer surprisingly modern twists on traditional texts. The third chapter is about Jewish online dating. It uses JDate and other secular websites to analyze how Jewish singles are using the Internet. This chapter also suggests that the use of the Internet may have an impact on reducing interfaith marriage. The fourth chapter examines marginalized communities, focusing on the following: Jewrotica; the Jewish LGBT community including those who are “OLGBT” (Orthodox LGBT); Punk Jews; and feminist Jews. -

11 Th Annual Tribute Dinner Virtual Cocktail Reception

Aish Thornhill Community Shul 11 th Annual Tribute Dinner Virtual Cocktail Reception Honouring Patti Dolman with the TzarchEi Tzibur Award Monday May 31st, 2021 at 8 p.m. In The Comfort of Your Own Home Virtual interactive cocktail demonstration with Bartender Mixologist, Josh Mellet PLEASE JOIN The Aish Thornhill Community Shul AT OUR 11 th Annual Tribute Dinner Virtual Cocktail Reception HONOURING Patti Dolman with The Tzarchei Tzibur Award Monday May 31st, 2021 • 8:00 PM In The Comfort of Your Own Home Virtual inter active cocktail demonstration with Bartender Mixologist Josh Mellet Amazing Online Silent Auction Program WELCOME BY Murray Nightingale PRESIDENT OF THE AISH THORNHILL COMMUNITY SHUL HATIKVAH AND O’CANADA LED BY Brian Callan D’VAR TOR AH Rabbi Avram Rothman SENIOR R ABBI OF THE AISH THORNHILL COMMUNITY SHUL PRESENTATION OF THE TZARCHEI TZIBUR AWARD TO Patti Dolman PRESENTED BY R ABBI AVR AM ROTHMAN INTERACTIVE COCKTAIL PRESENTATION BY BARTENDER MIXOLOGIST Josh Mellet CLOSING REMARKS BY Murray Nightingale ONLINE SILENT AUCTION WILL CLOSE THURSDAY JUNE 3RD AT 10:30 P.M. Board of Directors Rabbi Avram Rothman, Phd, Senior Rabbi Murray Nightingale, President Brian Callan Rebeca Finkelshtein Irving Ginzburg Sharlene Goldstein David Grabel Robert Morris Paul Paskovatyi Dalya Rothman Shul Staff Rabbi Avram Rothman, Phd, Senior Rabbi Office and Program Staff Hadassah Hoffer, Assistant to Rabbi Rothman Robert Walker, Program Director Wendy Sacks, Bookkeeper David Toledano, Youth Director Dear Friends, It is over a year ago that we all found ourselves in a Pandemic. As troubling as it was, we looked at it as novel, a time to be creative and develop ways to keep our community united, strong and growing. -

Knessia Gedolah Diary

THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN 0021-6615) is published monthly, in this issue ... except July and August, by the Agudath lsrael of Ameri.ca, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y. The Sixth Knessia Gedolah of Agudath Israel . 3 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N.Y. Subscription Knessia Gedolah Diary . 5 $9.00 per year; two years, $17.50, Rabbi Elazar Shach K"ti•?111: The Essence of Kial Yisroel 13 three years, $25.00; outside of the United States, $10.00 per year Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetzky K"ti•?111: Blessings of "Shalom" 16 Single copy, $1.25 Printed in the U.S.A. What is an Agudist . 17 Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman K"ti•?111: RABBI NISSON WotP!N Editor An Agenda of Restraint and Vigilance . 18 The Vizhnitzer Rebbe K"ti•'i111: Saving Our Children .19 Editorial Board Rabbi Shneur Kotler K"ti•'i111: DR. ERNST BODENHEIMER Chairman The Ability and the Imperative . 21 RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Helping Others Make it, Mordechai Arnon . 27 JOSEPH FRJEDENSON "Hereby Resolved .. Report and Evaluation . 31 RABBI MOSHE SHERER :'-a The Crooked Mirror, Menachem Lubinsky .39 THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not Discovering Eretz Yisroel, Nissan Wolpin .46 assume responsibility for the Kae;hrus of any product or ser Second Looks at the Jewish Scene vice advertised in its pages. Murder in Hebron, Violation in Jerusalem ..... 57 On Singing a Different Tune, Bernard Fryshman .ss FEB., 1980 VOL. XIV, NOS. 6-7 Letters to the Editor . • . 6 7 ___.., _____ -- -· - - The Jewish Observer I February, 1980 3 Expectations ran high, and rightfully so. -

20903 Hamoar Cover 4/9/09 07:05 Page 1 20903 Hamoar Cover 7/9/09 09:56 Page 2 20903 Hamoar Sept 2009 7/9/09 10:12 Page 1

20903 Hamoar cover 4/9/09 07:05 Page 1 20903 Hamoar cover 7/9/09 09:56 Page 2 20903 Hamoar Sept 2009 7/9/09 10:12 Page 1 EDITORIAL Contents Shanah Tovah Welcome to the new year of 5770, I Diary 2 hope you enjoy this latest edition of An insight into “Chalak Beit Yosef” 6 Hamaor, which is packed with a wide range of articles that offers CST - Speak up 9 something of interest to everyone. Do not cast us out in the time of our old age 10 From in-depth Halachic analysis provided by the Rosh Beth Din, Dayan YY Lichtenstein to a report by Sarah Rosh Hashana - Anticoni about the future developments for women Yom Teruah or Yom Zikhron Teruah? 12 within the Federation of Synagogues. Nine 14 We also have some reflections about Rosh Hashanah The Role of Women in the Federation 16 from the Chief Executive, Dr Eli Kienwald and the Family Hamoar Yeshurun’s Rabbi Alan Lewis, as well as an inspiring account about Recha and Isaac Sternbuch efforts to The Rosh Hashana Duet 18 save their fellow Jews during the time of the Book Review - A Time to Speak 20 Holocaust. Return to der Heim 22 Mark Harris updates us as to the regeneration of Hoping to help stillbirth parents 26 communities in Poland and you’ll find delicious new twists to traditional recipes in Family Hamaor. If you’re Recha and Isaac Sternbuch 28 looking for a new book for the New Year then don’t Recipes 30 miss the review of Martin Stern’s latest publication. -

Box Folder 69 17 Jewish Disappearance. Articles and Notes

MS-763: Rabbi Herbert A. Friedman Collection, 1930-2004. Series I: Wexner Heritage Foundation, 1947-2004. Subseries 2: Writings and Addresses, 1947-2003. Box Folder 69 17 Jewish disappearance. Articles and notes. 1996-2003. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org THE RESURRECTION OF AROCK AGENT By Michael Gross JULY 14 , 1997 Are American Jews Disappearing? BY CRAIG HOROWITZ .. ... .. ; :. :; f ·.· $2.95 1ca ..da 53.951 ·.. .. -.· . ... ·. i. 1• t •t t *"" c ' t l\ ~"'c "" ....... J"°"""~ 8', ~'1- he fundamenrai :Zionist anaiysis has naen 'Jinciica1eri: ~ • 1'" ...... YI CL ~'"'~ ... ')... • .... ""t .. -. ~ith Th e iaij o'f 1h e gneTTOw ails. ~he r e c: n be no furure for a s ec~ i a r. srateiess I ! .A -t t ~ ~ ~ _y)-l (}~ Vanishing ./ {·l .J / As American je,,·s fail to reproduce. and as they intermarry, they are facing cultural extinction. By Ari Shavit ,~stt(C IS RAEL ~ ~ jw''l!t(~ mother, 2.6; hardly any inter House, 2 Supreme Court jus- bold attempts at a countcr marriages), Jewish America cices and the president of the offensive - proclaiming a Jew seems to be engaged in a process Federal Reserve Board - it ish Revival, gathering again ir of demographic suicide (average seems American Jews have fi- the synagogues - the overal age, 39; average number of births nally arrived. With scores of trend is unquestionable: the rat< per mother, 1.6; a rate of inter Nobel Prize winners and Wall of intermarriage keeps climb marriage exceeding 52 percent). -

What Are You Learning This Holiday?

NCSY’s National Board presents: WHAT ARE YOU LEARNING THIS HOLIDAY? A Guide to an Inspirational Shavuos LETTER FROM RABBI DOVID BASHEVKIN 3 LETTER FROM NCSY’S TEEN PRESIDENT 4 THOUGHTS FROM NCSY’S NATIONAL BOARD 5 THOUGHTS FROM REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVES 10 FUN PAGES 16 MAKING TORAH YOURS Google has a fascinating employee policy. While all Google engineers spend the majority of their time dedicated to organizational business, they are also encour- aged to spend 20% of their time working on projects they find interesting. Many of Google’s most famous initiatives have come as the result of the 20% of time em- ployees spend on their own projects. In fact, Gmail, Google’s famed emailed ser- vice, is the product of someone’s 20% of time allotted to their personal initiatives. One Google executive estimated that 50% of new Google products are the result of the 20% of time employees are encouraged to spend on their own products. Torah innovation operates in a similar way. Of course, we spend most of our time immersed in the Torah ideas of the great Jewish leaders that precede us. Whether is it Chumash, Rashi, Talmud, or more recent Torah works, we look to our past to receive guidance for our future. Still, the importance of developing your own voice and ideas in Torah cannot be understated. In fact, the Talmud in Pesachim (68b) cites a disagreement which holidays require a personal compo- nent of celebration. The disagreement surrounds whether Jewish holidays should just be about prayer and learning or do they also demand a personal element, like a festive meal. -

The Haredim As a Challenge for the Jewish State. the Culture War Over Israel's Identity

SWP Research Paper Peter Lintl The Haredim as a Challenge for the Jewish State The Culture War over Israel’s Identity Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs SWP Research Paper 14 December 2020, Berlin Abstract ∎ A culture war is being waged in Israel: over the identity of the state, its guiding principles, the relationship between religion and the state, and generally over the question of what it means to be Jewish in the “Jewish State”. ∎ The Ultra-Orthodox community or Haredim are pitted against the rest of the Israeli population. The former has tripled in size from four to 12 per- cent of the total since 1980, and is projected to grow to over 20 percent by 2040. That projection has considerable consequences for the debate. ∎ The worldview of the Haredim is often diametrically opposed to that of the majority of the population. They accept only the Torah and religious laws (halakha) as the basis of Jewish life and Jewish identity, are critical of democratic principles, rely on hierarchical social structures with rabbis at the apex, and are largely a-Zionist. ∎ The Haredim nevertheless depend on the state and its institutions for safeguarding their lifeworld. Their (growing) “community of learners” of Torah students, who are exempt from military service and refrain from paid work, has to be funded; and their education system (a central pillar of ultra-Orthodoxy) has to be protected from external interventions. These can only be achieved by participation in the democratic process. ∎ Haredi parties are therefore caught between withdrawal and influence. -

Chabad- Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere Sharrona Pearla a University of Pennsylvania Published Online: 09 Sep 2014

This article was downloaded by: [University of Pennsylvania] On: 11 September 2014, At: 10:53 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Media and Religion Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hjmr20 Exceptions to the Rule: Chabad- Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere Sharrona Pearla a University of Pennsylvania Published online: 09 Sep 2014. To cite this article: Sharrona Pearl (2014) Exceptions to the Rule: Chabad-Lubavitch and the Digital Sphere, Journal of Media and Religion, 13:3, 123-137 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15348423.2014.938973 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

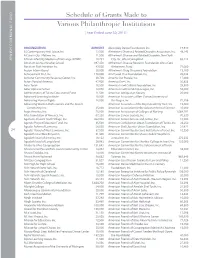

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

De-Constructing the Outreach-Inreach Debate Prof

4 JERUSALEM PAPERS ON JEWISH CONTINUITY AN OPEN FORUM ON EDUCATIONAL POLICY AND h PRACTICE De-Constructing the Outreach-Inreach Debate Prof. Steven Cohen November 1996 The Melton Centre for Jewish Education The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus, Jerusalem 91905 Israel De-Constructing the Outreach-Inreach Debate Steven M. Cohen The Melton Centre for Jewish Education The Hebrew University in Jerusalem As is widely recognized, the concern for Jewish continuity has stood at the top of the organized Jewish community's agenda, at least for the last five years or so. Quite naturally, the issue has provoked a number of key strategic debates. One of the earliest was between what may be called "associationists" and "educationists." Another divides the education ists into two camps: the advocates of "near-inreach," and the proponents of'Tar-outreach" (Cohen 1993). With regard to the first debate, by associationists I refer to those who believe the main goal of what have been called "Jewish continuity" programs is to increase opportunities for Jewish association, to bring Jews together, especially single young adult Jews. The principal aim here is to encourage them to engage in romance, marriage, and parenting. In con trast, Jewish educators, rabbis, enlightened lay leaders and communal professionals (as well as their high-paid social science consultants) have argued for a different approach. They contend that Jewish continuity de mands Jewish content, that association is only a necessary, but not a suffi cient, step to promoting a higher quality of Jewish life. For them, Jewish education - in some form, if not in all its forms - is the sine qua non of the Jewish continuity enterprise.