What Would Jonah Do

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Historical Clock

Reigns of Rulers of the Kingdom of Bohemia Louxenburg Kings Elected Czech King Jagelonians Austro Hungary Habsburgs Czechoslovakia Communist Czechoslovakia Czech Republic Wenceslav IV Sigismund George of Podiebrad Vladislav Ludwig Ferdinand I Maximilian II Rudolph II Mathias Ferdinand II Ferdinand III Leopold I Joseph I Karl VI Maria Theresia Joseph II Leopold II Franz II Ferdinand I of Austro Hungary Franz Joseph Masaryk/Benes Havel 1378/1419 1419/1437 1458/1471 1471/1516 1516/1526 1526/1564 1564/1576 1576/1612 1612/1619 1619/1637 1637/1657 1658/1705 1705/1711 1711/1740 1740/1780 1780/1790 1790/1792 1792/1835 1835/1848 1848/1916 1918/1939 1948/1990 1990 to date Husite Rebelion Jan Hus Burned 1415 Jan Ziska d. 1439 Lev of Rozhmithall d. 1480 Jewish Historical Clock - Branches From The Start Of The Horowitz Family Name In Prague Up To The Horowitz Dynasty In Dzikow/Tarnobrzeg Poland Giving Estimates Of Birth Years For Each Generation 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 1382/1406 1406/1430 1430/1454 1454/1478 1478/1502 1502/1526 1526/1550 1550/1574 1574/1598 1598/1622 1622/1646 1646/1670 1670/1694 1694/1718 1718/1742 1742/1766 1766/1790 1790/1814 1814/1838 1838/1862 1862/1886 1886/1910 1910/1934 1934/1958 1958/1982 1982/2006 S R. Yosef Yoske R. Asher Zeligman R. Meir ben Asher Jan(Yona) Halevy Ish R. Yosef of Vilna R. Yehoshua Heshel R. Chaim Cheika R. -

Download Full Journal (PDF)

SAPIR A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATIONS THE ISSUE ON POWER ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER RUTH CALDERON · MONA CHAREN MARK DUBOWITZ · DORE GOLD FELICIA HERMAN · BENNY MORRIS MICHAEL OREN · ANSHEL PFEFFER THANE ROSENBAUM · JONATHAN D. SARNA MEIR SOLOVEICHIK · BRET STEPHENS JEFF SWARTZ · RUTH R. WISSE Volume Two Summer 2021 And they saw the God of Israel: Under His feet there was the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, like the very sky for purity. — Exodus 24: 10 SAPIR Bret Stephens EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mark Charendoff PUBLISHER Ariella Saperstein ASSO CIATE PUBLISHER Felicia Herman MANAGING EDITOR Katherine Messenger DESIGNER & ILLUSTRATOR Sapir, a Journal of Jewish Conversations. ISSN 2767-1712. 2021, Volume 2. Published by Maimonides Fund. Copyright ©2021 by Maimonides Fund. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Maimonides Fund. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. WWW.SAPIRJOURNAL.ORG WWW.MAIMONIDESFUND.ORG CONTENTS 6 Publisher’s Note | Mark Charendoff 90 MICHAEL OREN Trial and Triage in Washington 8 BRET STEPHENS The Necessity of Jewish Power 98 MONA CHAREN Between Hostile and Crazy: Jews and the Two Parties Power in Jewish Text & History 106 MARK DUBOWITZ How to Use Antisemitism Against Antisemites 20 RUTH R. WISSE The Allure of Powerlessness Power in Culture & Philanthropy 34 RUTH CALDERON King David and the Messiness of Power 116 JEFF SWARTZ Philanthropy Is Not Enough 46 RABBI MEIR Y. SOLOVEICHIK The Power of the Mob in an Unforgiving Age 124 ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER Power and Ethics in Jewish Philanthropy 56 ANSHEL PFEFFER The Use and Abuse of Jewish Power 134 JONATHAN D. -

Rosh Hashanah Ubhct Ubfkn

vbav atrk vkp, Rosh HaShanah ubhct ubfkn /UbkIe g©n§J 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, hear our voice. /W¤Ng k¥t¨r§G°h i¤r¤eo¥r¨v 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, give strength to your people Israel. /ohcIy ohH° jr© px¥CUb c,§ F 'UbFknUbh© ct¨ Avinu Malkeinu, inscribe us for blessing in the Book of Life. /vcIy v²b¨J Ubhkg J¥S©j 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, let the new year be a good year for us. 1 In the seventh month, hghc§J©v J¤s«jC on the first day of the month, J¤s«jk s¨j¤tC there shall be a sacred assembly, iIº,C©J ofk v®h§v°h a cessation from work, vgUr§T iIrf°z a day of commemoration /J¤s«et¨r§e¦n proclaimed by the sound v¨s«cg ,ftk§nkF of the Shofar. /U·Gg©, tO Lev. 23:24-25 Ub¨J§S¦e r¤J£t 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /c«uy o«uh (lWez¨AW) k¤J r¯b ehk§s©vk Ub²um±uuh¨,«um¦nC Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l’hadlik ner shel (Shabbat v’shel) Yom Tov. We praise You, Eternal God, Sovereign of the universe, who hallows us with mitzvot and commands us to kindle the lights of (Shabbat and) Yom Tov. 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /v®Z©v i©n±Zk Ubgh°D¦v±u Ub¨n±H¦e±u Ub²h¡j¤v¤J Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, shehecheyanu v’kiy’manu v’higiyanu, lazman hazeh. -

USY's Scooby Jew Convention

April 2015 5775 USY’s Scooby Jew Convention In This Issue: By Mayer Adelberg On February 20, 2015, over one hundred teens converged on the Flamingo From the Rabbi Resort and Spa in Santa Rosa, California. It was a weekend of Jewish Page 3 learning, ruah (spirit) and fun, and the theme for this fantastic convention was, none other than, Scooby Doo. The three-day convention, called ISS (Intensive Study Seminar), was the first convention of the year where eighth graders were invited. Although President’s they were part of their own semi-separate convention (8th Grade Shabba- Perspective ton), they still intermingled with the USYers for some programs and for Page 5 meals. ISS was a weekend of Judaism and Jewish learning. As Calendar a youth group Pages 14 & 15 which is part of the Conservative movement, New Frontier USY incorporates prayer April experiences into Birthdays our conventions; Page 21 for ISS these were held in transformed hotel rooms. April The approach was Anniversaries interactive and Page 22 non-traditional, while the fundamental elements of the services were kept intact. Programming is a major part of ISS. With programs that cover Judaism as well as programs that completely relate to USYers’ lives, it is an important 100% club element that takes planning and serious consideration. At ISS, we had programs such as Israeli Capture the Flag, Pe’ah it Forward (discussing Pages 23 & 24 Sh’mittah), Parsha Palooza, and Jewpardy (Jewish Jeopardy.) “ISS was an incredible experience where I got to meet people who other- contributions wise I wouldn’t have even known existed,” says Danielle Horovitz, an 8th Pages 25 & 26 grader in Saratoga USY attending her first convention. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

The Letters of Rabbi Samuel S. Cohon

Baruch J. Cohon, ed.. Faithfully Yours: Selected Rabbinical Correspondence of Rabbi Samuel S. Cohon during the Years 1917-1957. Jersey City: KTAV Publishing House, 2008. xvii + 407 pp. $29.50, cloth, ISBN 978-1-60280-019-9. Reviewed by Dana Evan Kaplan Published on H-Judaic (June, 2009) Commissioned by Jason Kalman (Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion) Samuel S. Cohon is a largely forgotten fgure. became popular, was deeply interested in Jewish The results of googling his name are quite limited. mysticism. Cohon helped guide the Reform move‐ Michael A. Meyer discusses him in his Response to ment through difficult terrain at a critical time in Modernity and a select number of other writers American Jewish history. Cohon is best known for have analyzed specific aspects of his intellectual his drafting of “The Columbus Platform: The Guid‐ contribution to American Reform Judaism, but ing Principles for Reform Judaism,” which is seen there has been relatively little written about Co‐ as having reversed the anti-Zionism of the “Pitts‐ hon.[1] The American Jewish Archives in Cincin‐ burgh Platform” of 1885. He is also of historical nati, Ohio, has an extensive collection of his pa‐ importance because of the role that he played in pers, and booksellers still stock a number of his critiquing the Union Prayer Book (UPB), which books, but most American Jews have no idea who was the prayer book in virtually every Reform he was. Even those with a serious interest in temple from the end of the nineteenth century American Jewish history or Reform Judaism are until the publication of The Gates of Prayer: The unlikely to know very much about him. -

Erev Rosh Hashana 5776 Avinu Malkeinu Rabbi Vernon Kurtz

EREV ROSH HASHANA 5776 AVINU MALKEINU RABBI VERNON KURTZ As we gather here on the eve of Rosh Hashana, I must tell you I can’t wait for the end of Neilah on Yom Kippur. And, it is not for the reason you are thinking of. The last prayer that we recite in the Neilah service is the Avinu Malkeinu prayer. In full-throated singing our community joins together to chant one last time the final verse of that ancient prayer. As the Ark is closed I always feel that our prayers have wings going up to heaven in this last moment of the Ten Days of Penitence. It is a special moment for me and, I think, for all of us. We commence our High Holy Day experience this evening as one community and we conclude it at Neilah in the same fashion. The prayer Avinu Malkeinu, not only because of its last verse, but because of its history and meaning, is a central one to the High Holiday liturgy. We recite it every day of the Ten Days of Penitence except for Shabbat when penitential prayers such as these are not considered appropriate. In time for the High Holy Day season a new book appeared, edited by Rabbi Lawrence Hoffman. It is entitled Naming God – Avinu Malkeinu - Our Father, Our King. Authors from across the globe wrote essays about the prayer, its history, language, metaphors, lessons about G- d and about us, and its meaning for today. We know that Avinu Malkeinu is one of our most ancient prayers. -

Shavuot Daf Hashavua

בס״ד ׁשָ בֻ עוֹת SHAVUOT In loving memory of Harav Yitzchak Yoel ben Shlomo Halevi Volume 32 | #35 Welcome to a special, expanded Daf Hashavua 30 May 2020 for Shavuot at home this year, to help bring its 7 Sivan 5780 messages and study into your home. Chag Sameach from the Daf team Shabbat ends: London 10.09pm Sheffield 10.40pm “And on the day of the first fruits…” Edinburgh 11.05pm Birmingham 10.22pm (Bemidbar 28:26) Jerusalem 8.21pm Shavuot starts on Thursday evening 28 May and ends after Shabbat on 30 May. An Eruv Tavshilin should be made before Shavuot starts. INSIDE: Shavuot message Please look regularly at the social media and websites by Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis of the US, Tribe and your community for ongoing updates relating to Coronavirus as well as educational programming Megillat Rut and community support. You do not need to sign by Pnina Savery into Facebook to access the US Facebook page. The US Coronavirus Helpline is on 020 8343 5696. Mount Sinai to Jerusalem to… May God bless us and the whole world. the future Daf Hashavua by Harry and Leora Salter ׁשָ בֻ עוֹת Shavuot Shavuot message by Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis It was the most New York, commented that from stunning, awe- here we learn that the Divine inspiring event revelation was intended to send a that the world has message of truth to everyone on ever known. Some earth - because the Torah is both three and a half a blueprint for how we as Jews millennia ago, we should live our lives and also the gathered as a fledgling nation at the foundational document of morality foot of Mount Sinai and experienced for the whole world. -

INTRODUCING SIDDUR LEV CHADASH Charles H Middleburgh on Behalf of John D Rayner

33¢, INTRODUCING SIDDUR LEV CHADASH Charles H Middleburgh on behalf of John D Rayner On this momentous day in our movement’s history I stand here to perform a function that all of us would have liked John Rayner to have been able to carry out. John is recovering well from his heart surgery and we send him our sincere good wishes for a refitah sh ’lemah, a speedy return to full health and vigour. In his unavoidable absence, and based almost totally on the text he would have delivered to you all, it therefore gives me great pleasure(although the phrase has rarely seemed less adequate) to present to this conference, and to the Union of Liberal and Progressive Synagogues, the long-awaited Siddur Lev Chadash. I do so on behalf of the Editorial Committee and all who have been involved in the compilation and production of the book. It has been said that objectivity is a fine quality that each of us should develop, and I dare say that there are many who would approach the presentation of Siddur Lev Chadash with far greater objectivity than do I; my excuse then for being here, in spite of my irrcdeemably subjective approach to my present task is that I do, at least, have the advantage of - knowing the new book rather well just as a parent knows its child; r‘ if. except, of course, that this particular child is biologically unusual in that its gestation has taken several years, and that it has a plurality of COLLEG mothers and fathers, otherwise known as the Editorial Committee. -

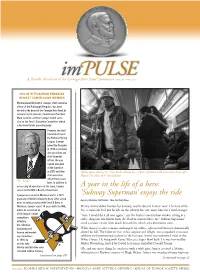

ISSUE 14 • JUNE 2008 a Periodic Newsletter of the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission �

im ULSEISSUE 14 • JUNE 2008 A Periodic Newsletter of the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission CEO OF PITTSBURGH PENGUINS NEWEST COMMISSION MEMBER Montreal-born Kenneth G. Sawyer, chief executive officer of the Pittsburgh Penguins, has been elected to the board of the Carnegie Hero Fund. In announcing the election, Commission President Mark Laskow said that Sawyer would serve also on the Fund’s Executive Committee, which is the Hero Fund’s awarding body. Formerly the chief financial officer of the National Hockey League, Sawyer joined the Penguins in 1999 as executive vice president and chief financial officer. He was named president of the franchise in 2003 and then Wesley James Autrey, Sr., New York’s subway hero. Photo reprinted with permission from Josh chief executive Haner/The New York Times/Redux. officer three years Mr. Sawyer later. In addition to overseeing all operations of the team, Sawyer A year in the life of a hero: serves on the NHL’s Board of Governors. Sawyer was raised in Montreal and is a 1971 ‘Subway Superman’ enjoys the ride graduate of McGill University there. After seven By Larry McShane, Staff Writer• New York Daily News years in public practice with Ernst & Ernst in Montreal, Sawyer spent 14 years with the NHL, Wesley Autrey didn’t hesitate last January, and he doesn’t hesitate now: The hero of the where he served on all No. 1 train says he’d put his life on the subway line one more time for a total stranger. of the league’s major “Sure, I would do it all over again,” says the fearless construction worker, sitting in a committees, coffee shop just two blocks from the Harlem station where the “Subway Superman” including saved a seizure victim from death beneath the wheels of a downtown train. -

The Bayit BULLETIN

ה׳ד׳ ׳ב׳ ׳ א׳ד׳ט׳ט׳ת׳ד׳ת׳ ׳ ׳ ד׳ר׳ב׳ד׳ ׳ב׳ד׳ ׳ ~ Hebrew Institute of Riverdale The Bayit BULLETIN June 5 - 12, 2015 18 - 25 Sivan 5775 Hebrew Institute of Riverdale - The Bayit Mazal Tov To: 3700 Henry Hudson Parkway Luba & David Teten on the birth of a son. To big sisters Leona, Peri and Sigal. Bronx, NY 10463 Rabbinic Intern Daniel Silverstein on being included in the Jewish Week’s 36 Under 36 most www.thebayit.org influential young Jewish Leaders for the year 2015. E-mail: [email protected] This Shabbat @ The Bayit Phone: 718-796-4730 Fax: 718-884-3206 LAST TENT CONNECTIONS AT ABRAHAM & SARAH’S TENT: More info on page 4. R’ Avi Weiss: [email protected]/ x102 KIDDUSH THIS SHABBAT IS SPONSORED BY THE TETEN FAMILY: In honor of R’ Sara Hurwitz: [email protected]/ x107 our new baby boy (Brit on Tuesday morning); Luba’s upcoming June birthday; and the great R’ Steven Exler: [email protected]/ x108 community helping us out with our new addition, especially Aimee & Jonathan Baron; Kathy R’ Ari Hart: [email protected]/ x124 Goldstein & Ahron Rosenfeld; Debra Kobrin & Daniel Levy; Shoshana Bulow; Elana & Bradley Saenger and Frederique & Andy Small. Kiddush SEUDA SHLISHIT: Join us after Mincha for Seuda Shlishit in the Social Hall. Sponsored by the Teten family. The Summer Celebration Kiddush This Sunday, June 7th @ The Bayit will be 6/20/2015. KAVVANAH TEFILLAH | 9:00am: An hour of slower tefillah with Rav Steven To sponsor visit www.thebayit.org/celebration including meditation & song. -

Newsletter December 2014 Volume 6, Number 2 Ira M

Newsletter December 2014 Volume 6, Number 2 Ira M. Sheskin Editor, University of Miami Professor and Chair, Department of Geography and Director, Jewish Demography Project of the Sue and Leonard Miller Center for Contemporary Judaic Studies American Jewish Year Book Special Price for ASSJ Members T he American Jewish Year Book is published by Springer with the cooperation of The Association for the Social Scientific Study of Jewry. The 935-page 2014 volume features ì a Forum on the Pew Survey (with contributions from Janet Krasner Aronson, Sarah Bunin Benor, Steven M. Cohen, Alan Cooperman, Arnold Dashefsky, Sergio DellaPergola, Harriet Hartman, Samuel Heilman, Bethamie Horowitz, Ari Y. Kelman, Barry A. Kosmin, Deborah Dash Moore, Theodore Sasson, Leonard Saxe, Ira Sheskin, and Gregory A. Smith); í Gender in American Jewish Life by Sylvia Barack Fishman; î National Affairs by Ethan Felson; ï Jewish Communal Affairs by Lawrence Grossman; ð Jewish Population in the United States, 2014 by Ira M. Sheskin and Arnold Dashefsky; ñ The Demography of Canadian Jewry by Morton Weinfeld and Randal F. Schnoor; and ò World Jewish Population 2014 by Sergio DellaPergola. In addition, the volume contains up-to-date listings of Jewish Federations, Jewish Community Centers, Jewish social service agencies, national Jewish organizations, Jewish day schools, Jewish overnight camps, Jewish museums, Holocaust museums, national Jewish periodicals and broadcast media, local Jewish periodicals, Jewish studies, holocaust and genocide studies programs, Israel studies programs, as well as Jewish social work programs in institutions of higher education, major books, journals, and scholarly articles on the North American Jewish 2 The Association for the Social Scientific Study of Jewry Vol.