EU UN Gowan and Brantner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion: Europe Is Worth It – for a Green Recovery Rooted in Solidarity and A

German Bundestag Printed paper 19/20564 19th electoral term 30 June 2020 version Preliminary Motion tabled by the Members of the Bundestag Agnieszka Brugger, Anja Hajduk, Dr Franziska Brantner, Sven-Christian Kindler, Dr Frithjof Schmidt, Margarete Bause, Kai Gehring, Uwe Kekeritz, Katja Keul, Dr Tobias Lindner, Omid Nouripour, Cem Özdemir, Claudia Roth, Manuel Sarrazin, Jürgen Trittin, Ottmar von Holtz, Luise Amtsberg, Lisa Badum, Danyal Bayaz, Ekin Deligöz, Katja Dörner, Katharina Dröge, Britta Haßelmann, Steffi Lemke, Claudia Müller, Beate Müller-Gemmeke, Erhard Grundl, Dr Kirsten Kappert-Gonther, Maria Klein-Schmeink, Christian Kühn, Stephan Kühn, Stefan Schmidt, Dr Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn, Markus Tressel, Lisa Paus, Tabea Rößner, Corinna Rüffer, Margit Stumpp, Dr Konstantin von Notz, Dr Julia Verlinden, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer, Gerhard Zickenheiner and the Alliance 90/The Greens parliamentary group be to Europe is worth it – for a green recovery rooted in solidarity and a strong 2021- 2027 EU budget the by replaced The Bundestag is requested to adopt the following resolution: I. The German Bundestag notes: A strong European Union (EU) built on solidarity which protects its citizens and our livelihoods is the best investment we can make in our future. Our aim is an EU that also and especially proves its worth during these difficult times of the corona pandemic, that fosters democracy, prosperity, equality and health and that resolutely tackles the challenge of the century that is climate protection. We need an EU that bolsters international cooperation on the world stage and does not abandon the weakest on this earth. proofread This requires an EU capable of taking effective action both internally and externally, it requires greater solidarity on our continent and beyond - because no country can effectively combat the climate crisis on its own, no country can stamp out the pandemic on its own. -

What Does GERMANY Think About Europe?

WHat doEs GERMaNY tHiNk aboUt europE? Edited by Ulrike Guérot and Jacqueline Hénard aboUt ECFR The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) is the first pan-European think-tank. Launched in October 2007, its objective is to conduct research and promote informed debate across Europe on the development of coherent, effective and values-based European foreign policy. ECFR has developed a strategy with three distinctive elements that define its activities: •a pan-European Council. ECFR has brought together a distinguished Council of over one hundred Members - politicians, decision makers, thinkers and business people from the EU’s member states and candidate countries - which meets once a year as a full body. Through geographical and thematic task forces, members provide ECFR staff with advice and feedback on policy ideas and help with ECFR’s activities within their own countries. The Council is chaired by Martti Ahtisaari, Joschka Fischer and Mabel van Oranje. • a physical presence in the main EU member states. ECFR, uniquely among European think-tanks, has offices in Berlin, London, Madrid, Paris, Rome and Sofia. In the future ECFR plans to open offices in Warsaw and Brussels. Our offices are platforms for research, debate, advocacy and communications. • a distinctive research and policy development process. ECFR has brought together a team of distinguished researchers and practitioners from all over Europe to advance its objectives through innovative projects with a pan-European focus. ECFR’s activities include primary research, publication of policy reports, private meetings and public debates, ‘friends of ECFR’ gatherings in EU capitals and outreach to strategic media outlets. -

German Arms Exports to the World? Taking Stock of the Past 30 Years

7/2020 PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE FRANKFURT / LEIBNIZ-INSTITUT HESSISCHE STIFTUNG FRIEDENS- UND KONFLIKTFORSCHUNG SIMONE WISOTZKI // GERMAN ARMS EXPORTS TO THE WORLD? TAKING STOCK OF THE PAST 30 YEARS PRIF Report 7/2020 GERMAN ARMS EXPORTS TO THE WORLD? TAKING STOCK OF THE PAST 30 YEARS SIMONE WISOTZKI // ImprInt LEIBNIZ-INSTITUT HESSISCHE STIFTUNG FRIEDENS- UND KONFLIKTFORSCHUNG (HSFK) PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE FRANKFURT (PRIF) Translation: Team Paraphrasis Cover: Leopard 2 A7 by Krauss-Maffei Wegmann (KMW), October 29, 2019. © picture alliance / Ralph Zwilling - Tank-Masters.de | Ralph Zwilling Text license: Creative Commons CC-BY-ND (Attribution/NoDerivatives/4.0 International). The images used are subject to their own licenses. Correspondence to: Peace Research Institute Frankfurt Baseler Straße 27–31 D-60329 Frankfurt am Main Telephone: +49 69 95 91 04-0 E-Mail: [email protected] https://www.prif.org ISBN: 978-3-946459-62-0 Summary The German government claims to pursue a restrictive arms export policy. Indeed, there are ample laws, provisions and international agreements for regulating German arms export policy. However, a review of 30 years of German arms export policy reveals an alarming picture. Although licences granted for arms exports to so-called third countries, which are neither part of the EU or NATO, nor equivalent states (Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and Switzerland), are supposed to be isolated cas- es with specific justifications, they have become the rule. In the past ten years alone, up to 60 per cent of German weapons of war and other military equipment has repeatedly been exported to third coun- tries. Not every arms export to third countries is problematic. -

Spotlight Europe # 2009/05 – May 2009 It's Hip to Be a Euro-Critic

spotlight europe # 2009/05 – May 2009 It's hip to be a euro-critic Isabell Hoffmann [email protected] Franziska Brantner [email protected] In the area of European policymaking, established parties are nowadays also confronted with pressure from the left-wing and right-wing fringes of the political spectrum. The fact is that, try as they might, they cannot ex- plain away all the negative results of EU policymaking. Instead of fighting a communications war from their entrenched positions, the supporters of European integration should recognize that there are contradictions in European policies which need to be dealt with frankly on a political level. Some people point out that the European And in fact after the referendum in Ireland Union was built on the basis of consensus, the European governments and the ad- whereas others warn that it needs contro- ministration in Brussels have tried to do versy, or else will lose its legitimacy. Jür- what they are best at: waiting until things gen Habermas and Günther Verheugen, have calmed down, conducting discreet two proponents of these opposing posi- talks, and preparing for another referen- # 2009/05 tions, crossed swords in the politics sec- dum. However, at the same time the de- tion of the Süddeutsche Zeitung in June bate on European policy, has already been 2008. “Politicize the debate,” demanded taken out on the streets. Not by the gov- the former. “Bring in the citizens.” “That ernments and the established political par- won’t work,” retorted the latter. “Europe is ties, but by players who do not have very based on consensus, and not on contro- deep roots in the system. -

Vergnüglicher Trubel in Der Altstadt Heidelberger Herbst Am 30

Amtsanzeiger der Stadt Heidelberg 27. September 2017 / Woche 39 / 25. Jahrgang Konversionsflächen Patrick-Henry-Village Heidelberger Dienste Bürgerforum zu Sickingenplatz Vorstellung des Zukunftsstadt- Seit 25 Jahren aktiv für und MTV West S. 5 › teils auf Messe Expo Real S. 7 › mehr Beschäftigung S. 9 › Vergnüglicher Trubel in der Altstadt Heidelberger Herbst am 30. September und 1. Oktober – Einkaufssonntag von 13 bis 18 Uhr er Heidelberger Herbst geht am Plätze, Stra- D 30. September und 1. Oktober ßen und in die 48. Runde: Am Samstag und Gassen sind Unterhaltung und Vergnügen auf vielen Altstadtplätzen: Das ist der Heidelberger Herbst. (Foto HD Marketing) Sonntag verwandelt sich die Altstadt gefüllt mit in ein buntes Meer aus Märkten, Marktständen: Entlang der Haupt- Stöbern und Feilschen ein. Der The- Tagen auf eine Puppenbühne am Konzerten, Aktionen und ausgelas- straße und im Innenhof des Kur- aterplatz wird zur „Oase der Ruhe“, Friedrich-Ebert-Platz freuen. Zudem sener Stimmung. pfälzischen Museums erstreckt sich in der temporäre Kunstwerke zu be- ö nen am Sonntag von 13 bis 18 Uhr Nach der o ziellen Erö nung am ein Kunsthandwerker- und Wa- wundern sind. zahlreiche Geschäfte im Stadtgebiet Samstag um 11 Uhr auf dem renmarkt. Der Universi- Am Sonntag konzentriert sich der ihre Türen für einen herbstlichen Marktplatz bieten auf tätsplatz verwandelt Heidelberger Herbst unter dem Mot- Einkaufsbummel. red insgesamt vierzehn sich in einen Mit- to „Familien-Herbst“ speziell auf Bühnen diverse Grup- FESTIVAL telaltermarkt und Eltern und Kinder. In der Altstadt Weitere Infos zum Heidelberger pen Live-Musik und in den Altstadt- wird auf acht Plätzen von 11 bis 19 Herbst und Einkaufssonntag unter Unterhaltung für je- Enjoy Jazz gassen laden Uhr Unterhaltung geboten. -

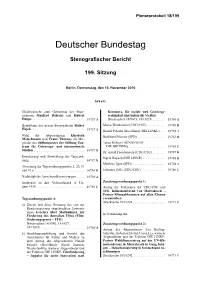

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a) -

Deutscher Bundestag Beschlussempfehlung Und Bericht

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/1948 18. Wahlperiode 01.07.2014 Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Ausschusses für Wahlprüfung, Immunität und Geschäftsordnung (1. Ausschuss) zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Irene Mihalic, Dr. Konstantin von Notz, Luise Amtsberg, Volker Beck (Köln), Frank Tempel, Jan Korte, Ulla Jelpke, Martina Renner, Jan van Aken, Agnes Alpers, Kerstin Andreae, Annalena Baerbock, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, Marieluise Beck (Bremen), Herbert Behrens, Karin Binder, Matthias W. Birkwald, Heidrun Bluhm, Dr. Franziska Brantner, Agnieszka Brugger, Christine Buchholz, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Roland Claus, Sevim Da÷delen,Dr.DietherDehm,EkinDeligöz,KatMaDörner,KatharinaDröge, Harald Ebner, Klaus Ernst, Dr. Thomas Gambke, Matthias Gastel, Wolfgang Gehrcke, Kai Gehring, Katrin Göring-Eckardt, Diana Golze, Annette Groth, Dr. Gregor Gysi, Heike Hänsel, Dr. André Hahn, Anja Hajduk, Britta Haßelmann, Dr. Rosemarie Hein, Inge Höger, Bärbel Höhn, Dr. Anton Hofreiter, Andrej Hunko, Sigrid Hupach, Dieter Janecek, Susanna Karawanskij, Kerstin Kassner, Uwe Kekeritz, Katja Keul, Sven-Christian Kindler, Katja Kipping, Maria Klein-Schmeink, Tom Koenigs, Sylvia Kotting-Uhl, Jutta Krellmann, Oliver Krischer, Stephan Kühn (Dresden), Christian Kühn (Tübingen), Renate Künast, Katrin Kunert, Markus Kurth, Caren Lay, Monika Lazar, Sabine Leidig, Steffi Lemke, Ralph Lenkert, Michael Leutert, Stefan Liebich, Dr. Tobias Lindner, Dr. Gesine Lötzsch, Thomas Lutze, Nicole Maisch, Peter Meiwald, Cornelia Möhring, Niema Movassat, Beate Müller-Gemmeke, Özcan Mutlu, Thomas Nord, Omid Nouripour, Cem Özdemir, Friedrich Ostendorff, Petra Pau, Lisa Paus, Harald Petzold (Havelland), Richard Pitterle, Brigitte Pothmer, Tabea Rößner, Claudia Roth (Augsburg), Corinna Rüffer, Manuel Sarrazin, Elisabeth Scharfenberg, Ulle Schauws, Dr. Gerhard Schick, Michael Schlecht, Dr. Frithjof Schmidt, Kordula Schulz-Asche, Dr. Petra Sitte, Kersten Steinke, Dr. Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn, Hans-Christian Ströbele, Dr. -

German Bundestag Motion

German Bundestag Printed Paper 19/22561 19th electoral term 16 September 2020 Motion by the Members of Parliament Omid Nouripour, Margarete Bause, Claudia Roth, Kai Gehring, Dr. Franziska Brantner, Agnieszka Brugger, Uwe Kekeritz, Katja Keul, Dr. Tobias Lindner, Cem Özdemir, Manuel Sarrazin, Dr. Frithjof Schmidt, Jürgen Trittin, Ottmar von Holtz and the Alliance 90 / Greens Parliamentary Group Iran - Condemn human rights violations and consistently de- mand obligations under international law The Bundestag is requested to adopt the following motion: I. The German Bundestag notes: Iran is a member of the United Nations, has voted for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and other international human rights treaties. In violation of these and other international obligations, human and civil rights are systematically dis- regarded and violated in Iran. Freedom of opinion, association and assembly are massively restricted by the au- thorities. Internet sites and social media are blocked, and critical media operations are closed. Initiatives for more women's rights are nipped in the bud. For example, the authorities take bitter action against activists who campaign against the dis- criminatory obligation to wear a headscarf - sometimes with decades of prison sentences or lashes. In addition, the authorities take extremely harsh action against human rights lawyers and prosecute them for their peaceful human rights work. In March 2019, the lawyer and winner of the European Parliament's Sakharov Human Rights Prize, Nasrin Sotoudeh, was sentenced to 33 years and six months in prison and to 148 lashes (https://www.zeit.de/2019/13/nasrin-sotoudeh- anwaeltin-iran-inhaftierung). -

The Future of European Solidarity”

Results of the 3rd Round of European HomeParliaments by Pulse of Europe: “The future of European solidarity” Status: 04.01.2021 Dear participants, dear politicians, Thanks to the support of EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and 30 ded- icated EU politicians, Pulse of Europe succeeded during this round of Euro- pean HomeParliaments in imple- menting innovations for the partic- ipation of citizens in EU politics. Pulse of Europe provides the first pan-European, scalable grassroots project for the participation of Euro- peans in EU policy decisions. It works both offline in a private environment and now also online via our Video HomeParliaments. Our mission is to create a per- manent, bottom-up format for engaging with EU policymakers. For the first time, late 2020 people from Ger- many, Austria, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, Portugal, Spain, Bulgaria and France exchanged their expectations for the EU. In addition, numer- ous cross-border HomeParliaments con- tributed to a transnational European dialogue. About 700 Europeans participated in local HomeParliaments. Another 500 discussed the future of European solidarity via the new Video HomeParliaments. As in the first two rounds of the European HomeParliaments, the participants of the privately organized discussion rounds were enthusiastic about the constructive exchange, the mutual understanding and the insights gained from the structured Click on the picture to see the video discussions about the future of European solidarity. EC Ursula von der Leyen The Video HomeParliaments enabled a special in- novation, among other things: a location-inde- Manfred Weber EPP Othmar Karas EPP pendent matching of participants, i.e. -

German Bundestag Motion

German Bundestag Printed paper 18/5385 18th electoral term 01.07.2015 Motion Tabled by the Members of the Bundestag Tom Koenigs, Uwe Kekeritz, Kordula Schulz-Asche, Özcan Mutlu, Omid Nouripour, Ulle Schauws, Cem Özdemir, Claudia Roth, Annalena Baerbock, Marieluise Beck, Dr Franziska Brantner, Agnieszka Brugger, Kai Gehring, Dr Tobias Lindner, Manuel Sarrazin, Dr Frithjof Schmidt, Jürgen Trittin, Doris Wagner, Luise Amtsberg, Katja Dörner, Tabea Rößner, Elisa- beth Scharfenberg, Hans-Christian Ströbele, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer and the Alliance 90/The Greens parliamentary group Strengthening relations between Germany and Namibia and living up to Germany's historical responsibility The Bundestag is requested to adopt the following motion: I. The German Bundestag notes: 1. The German Bundestag acknowledges the heavy burden of guilt carried by the German colonial forces as a result of their crimes against the He- rero, Nama, Damara and San, and emphasizes, as historians have long since proved, that the war of extermination in Namibia between 1904 and 1908 was a war crime and genocide. 2. The German Bundestag apologises to the descendants of the victims for the injustice and suffering inflicted upon their ancestors in Germany's name. 3. The German Bundestag emphasises the continuing historical and moral responsibility borne by Germany for the future of Namibia and for the ethnic groups affected by the genocide. The Bundestag previously de- clared this responsibility in its resolutions of April 1989 and June 2004. 4. The German Bundestag supports initiatives to deal with Germany's co- lonial past. 5. The German Bundestag fundamentally supports the dialogue process in- itiated in 2014 between the Government of the Republic of Namibia and the German Federal Government and points out that this must take place with the involvement of the affected sections of the population and civil society. -

An Open Letter to the Prime Minister, Minister for Women & Child Development and Minister of Social Justice & Empowerm

AN OPEN LETTER TO THE PRIME MINISTER, MINISTER FOR WOMEN & CHILD DEVELOPMENT AND MINISTER OF SOCIAL JUSTICE & EMPOWERMENT Prime Minister Mr. Narendra Modi Prime Minister’s Office South Block, Raisina Hill New Delhi - 110011 Ms. Smriti Zubin Irani Minister for Women and Child Development Shastri Bhawan New Delhi - 110001 Mr. Thaawarchand Gehlot Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment A-Wing, Shastri Bhawan New Delhi - 110001 June 28th, 2021 Dear Prime Minister Modi, dear Minister Irani, dear Minister Gehlot, With this letter we, the Members of Parliament, would like to express our utmost concern regarding the rising number of grave incidents of rape and sexual violence against Dalit women and girls, which have been taking place in India over the last few years. The horrific crime of gang rape and physical attack committed in Hathras on 14 September 2020 resulted in the death of a young Dalit woman. The case drew widespread outrage globally and is sadly not an isolated incident. Rather, the Hathras case represents a worrying trend of rapes against women and girls in India, particularly against marginalized communities, who face additional atrocities and are at increased risk of sexual violence. We are profoundly worried about the downplaying by key State officials of the grave criminal nature of sexual violence against women and girls, particularly when committed against marginalized communities. In the Hathras case, for instance, the Uttar Pradesh (UP) authorities initially denied that the rape took place, they cremated the body of the victim without the consent of the family, and arrested journalists and civil society activists protesting against these actions or reporting on the case. -

KA Nr.19-604 Bündnis90-Diegrünen EN

German Federal Foreign Office To the Walter J.Lindner President of the German Bundestag State Secretary of the German Federal Dr Wolfgang Schauble, Member of the Foreign Office German Bundestag Platz der Republik 1 11011 Berlin Berlin, 14 Feb. 2018 Minor interpellation submitted by the Members of the Bundestag Dr Frithjof Schmidt, Uwe Kekeritz, Margarete Bause, Kai Gehring, Dr Franziska Brantner, Agnieszka Brugger, Katja Keul, Dr Tobias Lindner, Omid Nouripour , Cem Özdemir, Claudia Roth , Manuel Sarrazin , Jürgen Trittin, Ottmar von Holtz and the Alliance 90/The Greens parliamentary group Bundestag printed paper No. 19-604 of 1 February 2018 Title - Democracy and Human Rights in Cambodia Dear President , Please find enclosed the answer of the Federal Government to the above-specified minor interpellation . Yours sincerely, Answer of the Federal Government to the minor interpellation submitted by the Members of the German Bundestag Dr Frithjof Schmidt, Uwe Kekeritz, Margarete Bause, Kai Gehring, Dr Franziska Brantner, Agnieszka Brugger, Katja Keul, Dr Tobias Lindner, Omid Nouripour. Cem Özdemir, Claudia Roth , Manuel Sarrazin , Jürgen Trittin , Ottmar von Holtz and the Alliance 90/The Greens parliamentary group - Bundestag printed paper No.:19-604 of 1 February 2018 – Democracy and Human Rights in Cambodia Preliminary remarks of the questioner Since the communal elections in June 2017, the dismantling of democracy and human rights in Cambodia has accelerated. This development is reflected with particular virulence in the government repression of the free press and the political opposition. Numerous radio stations and the English-language newspaper Cambodian Daily have been forced to close under the pretext of unpaid taxes.