"Being in the Wrong Place at the Wrong Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ubc Under Gr Adu a Te Journal of English

THE UBC UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF ENGLISH • THE• GARDEN • STATUARY VOLUME 9 WINTER 2019 $ SPRING 2020 ABOUT THE JOURNAL The Garden Statuary is the o!cial Undergraduate Journal of English at The University of British Columbia, operated and peer-reviewed by UBC undergraduate students. We publish twice a year online (once at the end of each term) and compile both online issues into a single end-of-year print edition. The journal began as the idea of a group of writers, artists, and musicians from a second year English honours class and has published 18 issues since September 2011. As “English” is a "eld of remarkable interdisciplinary richness and UBC students work in remarkably diverse mediums, we welcome a wide range of genres and forms: academic essays in the "eld of English, poetry, "ction, creative non"ction, stage and screenplay, photography, visual art, music, and "lm. Our mission is to provide a place for UBC undergraduates to showcase, celebrate, and share their work within the university and beyond. In turn, we hope we leave our student audiences feeling inspired and connected to the incredible energy and talent found in the community around them. If you are a UBC undergraduate and wish to see your work on our print and/or digital pages, please peruse our submission guidelines on our website www.thegardenstatuary.com. You can also contact us at [email protected]. We’re excited to see your work! VOLUME 9, WINTER 2019 2019 WINTER 9, VOLUME POETRY, FICTION, CREATIVE NON#FICTION, MULTIMEDIA AND ACADEMIC ESSAYS BY NOOR ANWAR • MABON FOO • SAGORIKA HAQUE • MOIRA HENRY VLAD KRAKOV • CAMILLE LEMIRE • ALGER LIANG • JADE LIU LISA LIU • TYLER ANTONIO LYNCH • LINDSEY PALMER • EMMY PEHRSON FRANCOIS PELOQUIN • MARIANNA SCHULTZ • AVANTIKA SIVARAMAN $ MARILYN SUN • AIDEN TAIT • AMANDA WAN • IRIS ZHANG 2020 SPRING FRONT COVER ILLUSTRATION BY IVY TANG COVER DESIGN BY GABRIELLE LIM PRINT ISSUE ASSEMBLED BY KRISTEN KALICHARAN VOLUME 9, ISSUE 1 ! WINTER 2019 *+,-./0*1/2,3-/4*56*+//.-728*9,3-,. -

Template EUROVISION 2021

Write the names of the players in the boxes 1 to 4 (if there are more, print several times) - Cross out the countries that have not reached the final - Vote with values from 1 to 12, or any others that you agree - Make the sum of votes in the "TOTAL" column - The player who has given the highest score to the winning country will win, and in case of a tie, to the following - Check if summing your votes you’ve given the highest score to the winning country. GOOD LUCK! 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Anxhela Peristeri “Karma” Albania Montaigne “ Technicolour” Australia Vincent Bueno “Amen” Austria Efendi “Mata Hari” Azerbaijan Hooverphonic “ The Wrong Place” Belgium Victoria “Growing Up is Getting Old” Bulgaria Albina “Tick Tock” Croatia Elena Tsagkrinou “El diablo” Cyprus Benny Christo “ Omaga “ Czech Fyr & Flamme “Øve os på hinanden” Denmark Uku Suviste “The lucky one” Estonia Blind Channel “Dark Side” Finland Barbara Pravi “Voilà” France Tornike Kipiani “You” Georgia Jendrick “I Don’t Feel Hate” Germany Stefania “Last Dance” Greece Daði og Gagnamagnið “10 Years” Island Leslie Roy “ Maps ” Irland Eden Alene “Set Me Free” Israel 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Maneskin “Zitti e buoni” Italy Samantha Tina “The Moon Is Rising” Latvia The Roop “Discoteque” Lithuania Destiny “Je me casse” Malta Natalia Gordienko “ Sugar ” Moldova Vasil “Here I Stand” Macedonia Tix “Fallen Angel” Norwey RAFAL “The Ride” Poland The Black Mamba “Love is on my side” Portugal Roxen “ Amnesia “ Romania Manizha “Russian Woman” Russia Senhit “ Adrenalina “ San Marino Hurricane “LOCO LOCO” Serbia Ana Soklic “Amen” Slovenia Blas Cantó “Voy a quedarme” Spain Tusse “ Voices “ Sweden Gjon’s Tears “Tout L’Univers” Switzerland Jeangu Macrooy “ Birth of a new age” The Netherlands Go_A ‘Shum’ Ukraine James Newman “ Embers “ United Kingdom. -

An Exploration of the Potential of Participatory Documentary Filmmaking in Rural India

Village Tales: an exploration of the potential of participatory documentary filmmaking in rural India Sue Sudbury A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bournemouth University January 2015 Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 2 A practice-led Phd This practice-led PhD follows the regulations as set out in Bournemouth University’s Code of Practice for Research Degrees. It consists of a 45 minute documentary film and an accompanying 29,390 word exegesis: ‘The exegesis should set the practice in context and should evaluate the contribution that the research makes to the advancement of the research area. The exegesis must be of an appropriate proportion of the submission and would normally be no less than 20,000 words or the equivalent…A full appreciation of the originality of the work and its contribution to new knowledge should only be possible through reference to both’. Extract from Code of Practice for Research Degrees, Bournemouth University, September 2014. A note on terminology The term ‘documentary’ refers to my own film informed by the documentary tradition in British film and television. ‘Ethnographic film’ refers to research-based filmmaking, often undertaken by visual anthropologists and/or ethnographers, and that research has also informed my own practice as a documentary filmmaker. -

Towards a Fifth Cinema

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Towards a fifth cinema Article (Accepted Version) Kaur, Raminder and Grassilli, Mariagiulia (2019) Towards a fifth cinema. Third Text, 33 (1). pp. 1- 25. ISSN 0952-8822 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/80318/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Towards a Fifth Cinema Raminder Kaur and Mariagiulia Grassilli Third Text article, 2018 INSERT FIGURE 1 at start of article I met a wonderful Nigerian Ph.D. -

Reversing the Gaze When (Re) Presenting Refugees in Nonfiction Film

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA ARTS (2020) Vol. 5, Nº. 2 pp. 82-99 © 2020 BY-NC-ND ijfma.ulusofona.pt doi: 10.24140/ijfma.v5.n2.05 TOWARDS A PARTICIPATORY APPROACH: REVERSING THE GAZE WHEN (RE) PRESENTING REFUGEES IN NONFICTION FILM RAND BEIRUTY* * Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF (Germany) 82 TOWARDS A PARTICIPATORY APPROACH RAND BEIRUTY Rand Beiruty is currently pursuing a practice-based Ph.D. at Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF. She is alumna of Berlinale Talents, Beirut Talents, Film Leader Incubator Asia, Documentary Campus, Locarno Documentary School and Ji.hlava Academy. Corresponding author Rand Beiruty [email protected] Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF Marlene-Dietrich-Allee 11, 14482 Potsdam Germany Paper submitted: 24th march 2020 Accepted for Publication: 26th September 2020 Published Online: 13th November 2020 83 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA ARTS (2020) Vol. 5, Nº. 2 Abstract Living in Germany during the peak of the “refugee crisis”, I was bombarded with constant reporting on the topic that clearly put forth a problematic representation of refugees, contributing to rendering them a ‘problem’ and the situation a ‘crisis’. This reflects in my own film practice in which I am frequently engaging with Syrian refugees as protagonists. Our shared language and culture made it easier for us to form a connection. However, as a young filmmaker, I felt challenged and conflicted by the complexities of the ethics of representation, especially when making a film with someone who’s going through a complex insti- tutionalized process. In this paper I explore how reflecting on my position within the filmmaking process affected my relationship with my film par- ticipants and how this reflection influenced my choice of documentary film form. -

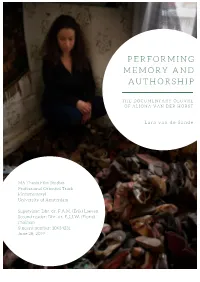

Performing Memory and Authorship

P E R F O R M I N G M E M O R Y A N D A U T H O R S H I P T H E D O C U M E N T A R Y O E U V R E O F A L I O N A V A N D E R H O R S T L a r a v a n d e S a n d e MA Thesis Film Studies Professional Oriented Track (Documentary) University of Amsterdam Supervisor: Dhr. dr. F.A.M. (Erik) Laeven Second reader: Dhr. dr. F.J.J.W. (Floris) Paalman Student number: 10634231 June 28, 2019 For my father Rien van de Sande (1947-2016) 2 Ugliness is beauty that cannot be contained within the soul. It is the transformational force of poetry or imagery, that is what you are looking for as a filmmaker, or an artist. Aliona van der Horst 3 Contents Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………...……7 Chapter 1: The rise of subjective documentary filmmaking…………………………………12 1.1 Origins: a cinema of auteurs……………………………………………………….12 1.2 The start of female documentary authorship ………………..............................14 1.3 Defining the practice: a mode instead of a genre…………………………………..17 Chapter 2: Memory, emotion & narrative…………………………………………………...20 2.1 Cognitive frameworks: narrative, emotion and memory ………………………….20 2.2 Media and memory: remembering (without) experience…………….....................22 2.3 Memory is mediated…………………………………………………..................24 2.4 Prosthetic memory: the artificial limb made of imagined memories………...….…..25 2.5 The filmic translation of personal memory………………………………………26 Chapter 3: Turning memory into narrative in Voices of Bam……………………………...…28 3.1 Voices of Bam’s narrative of experience: wandering through the rubble……………28 3.2 The inner voices talking: active remembering in direct address…………….……. -

The Tragic Muse, by Henry James 1

The Tragic Muse, by Henry James 1 The Tragic Muse, by Henry James The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Tragic Muse, by Henry James This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Tragic Muse Author: Henry James Release Date: December 10, 2006 [eBook #20085] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 The Tragic Muse, by Henry James 2 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TRAGIC MUSE*** E-text prepared by Chuck Greif, R. Cedron, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Europe (http://dp.rastko.net/) THE TRAGIC MUSE by HENRY JAMES MacMillan and Co., Limited St. Martin's Street, London 1921 PREFACE I profess a certain vagueness of remembrance in respect to the origin and growth of The Tragic Muse, which appeared in the Atlantic Monthly again, beginning January 1889 and running on, inordinately, several months beyond its proper twelve. If it be ever of interest and profit to put one's finger on the productive germ of a work of art, and if in fact a lucid account of any such work involves that prime identification, I can but look on the present fiction as a poor fatherless and motherless, a sort of unregistered and unacknowledged birth. I fail to recover my precious first moment of consciousness of the idea to which it was to give form; to recognise in it--as I like to do in general--the effect of some particular sharp impression or concussion. -

The Growth of VOD Investment in Local Entertainment Industries Contents

Asia-on- demand: the Growth of VOD Investment in Local Entertainment Industries contents Important Notice on Contents – Estimations and Reporting 04 GLOSSARY This report has been prepared by AlphaBeta for Netflix. 08 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY All information in this report is derived or estimated by AlphaBeta analysis using both 13 FACT 1: proprietary and publicly available information. Netflix has not supplied any additional data, nor VOD INVESTMENT IN LOCAL ASIAN CONTENT COULD GROW 3.7X BY 2022 does it endorse any estimates made in the report. Where information has been obtained from third party sources and proprietary sources, this is clearly referenced in the footnotes. 17 FACT 2: STRONG CONSUMER DEMAND INCENTIVIZES INVESTMENT IN HIGH-QUALITY Published in October 2018 LOCAL ENTERTAINMENT ONLINE 23 FACT 3: THROUGH VOD, ORIGINAL CONTENT PRODUCED IN ASIA IS GETTING INCREASED ACCESS TO GLOBAL AUDIENCES 27 FACT 4: THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF LOCAL CONTENT INVESTMENT IS 3X LARGER THAN WHAT VOD PLAYERS SPEND 32 FACT 5: VOD PLAYERS OFFER BENEFITS TO THE LOCAL INDUSTRY - WELL BEYOND LOCAL CONTENT INVESTMENT 38 FACT 6: THE CONTENT PRODUCTION VALUE CHAIN IS BECOMING MORE GLOBAL AND DIVERSE, ALLOWING ASIAN COUNTRIES TO SPECIALIZE 43 FACT 7: THE KEY DRIVERS TO CAPTURING THE VOD CONTENT OPPORTUNITY ARE INVESTMENT INCENTIVES, SUPPORTIVE REGULATION, AND AlphaBeta is a strategy and economic advisory business serving clients across Australia and HIGH-QUALITY INFRASTRUCTURE Asia from offices in Singapore, Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne. 54 FINAL THOUGHTS: IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICYMAKERS SINGAPORE Level 4, 1 Upper Circular Road 57 APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY Singapore, 058400 Tel: +65 6443 6480 Email: [email protected] Web: www.alphabeta.com glossary The following terms have been used at various stages in this report. -

Sermon Notes

The Resurrection Of Christ (With A Message To Seekers) Mark 15:40-16:8 Right now, our four-year old grandson, Calvin, likes to play hide and go seek, as does his 2 ½ year-old sister Margo. Each game seems to take longer than expected. Their hearts are in the right place, they are eager to play the game, but they don’t look in right places (and they can get a bit sidetracked) so it takes a while. Sometimes I have to make noises to redirect them to where I’m at. We are going to see something similar in the passage today; those whose hearts that are in the right place, but as they seek Jesus, He isn’t where they are looking. The passage this morning is the account of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. And when the women who have come to anoint His body with spices get to His tomb, He isn’t there. And if we were reading Luke, the angel at His tomb will ask these devoted followers, “Why are you seeking the living, among the dead?” “You’re looking in the wrong place.” The word seek is used throughout the Scriptures to describe a pursuit of something we desire, whether it’s good for us or not. For instance, the bride in the Song of Solomon says this in 3:2. “I must arise now and go about the city; in the streets and in the plazas. I must seek him whom my soul loves. I sought him but did not find him.” I don’t she gave up. -

Discurso Y Comunicación

GRUPO TEMÁTICO 14 Discurso y Comunicación 2 El falso documental como supuesto tercer espacio: revisiones críticas a una aritmética cinematográfica Sergio José Aguilar Alcalá 7 La potencia narrativa de los fotolibros Marina Feldhues 13 Estudiar la ideología desde el discurso: Los complejos ideológicos de la Reforma Energética de 2013 en México Axel Velázquez Yáñez 19 La construcción del ethos discursivo del científico en los blogs de divulgación científica brasileños Natália Martins Flores & Isaltina Maria de Azevedo Mello Gomes 26 Jóvenes en Argentina: vulnerabilidad simbólica y mediática Fabiana Martínez 32 “Malvinas entre el reclamo y el olvido: disputas discursivas a 30 años de la guerra” Claudia Guadalupe Grzincich & María Ercilia Alaniz 37 Os personagens de HQs e o consumo de tatuagens Matheus Eurico Noronha & Daniela Cunha Fernandes Miranda 43 El narcotráfico como fenómeno social recreado en el discurso de la prensa en México Édgar Ávila González & Gabriela Sánchez Medina 52 ¿Persona non grata? Las representaciones de Michel Temer en Carta Capital André Mendes & Jonaina Barcelos 59 “El pueblo necesita colaborar”: Un análisis lexicográfico de los discursos de posesión de Michel Temer en 2016 Franco Iacomini Junior & Torcis Prado Junior & Moisés Cardoso 67 Netflix: del procesamiento de la información a la reinterpretación de la cultura Eliseo Colón Zayas 73 3 Discurso hegemónico y contradiscurso: análisis crítico del discurso mediático sobre el conflicto amazónico el “Baguazo”. Franklin Guzmán Zamora 78 Criatividade, poder e inspiração: TED talks e sua retórica desterritorializada Carolina Cavalcanti Falcão 85 Discurso y Comunicación en la historia de la música romántica mexicana Tanius Karam Cárdenas 90 Imágenes de la nación y nuevo populismo político-mediático entre Brasil y Perú: una mirada semiótico-discursiva Paolo Demuru & Elder Cuevas-Calderón 95 Géneros, tradiciones discursivas y tecnologías. -

Home Fire : a Novel / Kamila Shamsie

Also by Kamila Shamsie In the City by the Sea Salt and Saffron Kartography Broken Verses Burnt Shadows A God in Every Stone RIVERHEAD BOOKS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC 375 Hudson Street New York, New York 10014 Copyright © 2017 by Kamila Shamsie Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Shamsie, Kamila [date], author. Title: Home fire : a novel / Kamila Shamsie. Description: New York : Riverhead Books, 2017. Identifiers: LCCN 2017003238 | ISBN 9780735217683 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Families—Fiction. | Domestic fiction. | Political fiction. | BISAC: FICTION / Family Life. | FICTION / Political. | FICTION / Cultural Heritage. | GSAFD: Love stories. Classification: LCC PR9540.9.S485 H66 2017 | DDC 823/.914—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017003238 p. cm. Ebook ISBN: 9780735217706 This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Version_1 For Gillian Slovo Contents Also by Kamila Shamsie Title Page Copyright Dedication Epigraph Isma Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Eamonn Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Parvaiz Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Aneeka Chapter 7 Karamat Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Acknowledgments About the Author The ones we love . -

Daughters May Spark Jump Start's Legacy

THURSDAY, MAY 23, 2019 DAUGHTERS MAY SPARK PET AND MRI: A BRAVE NEW DIAGNOSTIC WORLD by Dan Ross JUMP START'S LEGACY Earlier this month, The Stronach Group announced the arrival later this year at Santa Anita of the Longmile Positron Emission Tomography (MILE-PET) Scan machine--a technology currently under development at California's UC Davis, that could revolutionize the diagnosis of emerging lower limb injuries that could deteriorate into something catastrophic. But Santa Anita's new PET scan machine might not be the only important development at the track. According to CHRB equine medical director Rick Arthur, efforts are afoot to possibly bring a standing MRI to Santa Anita. The MRI machine's possible arrival raises some interesting tensions between the two diagnostic modalities. Indeed, proponents of both technologies argue passionately about their individual merits in early injury detection. But what isn't up for debate is how they both present a win for the horse. Cont. p5 Jump Start | Northview Stallion Station by Chris McGrath IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Here's a hunch, even a wager if you care to stick around long enough. Because I wouldn't be at all surprised should we SHAMARDAL A SIRE OF THE HIGHEST CLASS someday notice the damsire of a new champion and remember, John Boyce examines the stud career of Shamardal, who has made a strong start to 2019. with a smile, the splendid Jump Start. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. Pennsylvanian breeders won't need telling what a dynamo among stallions they lost on Sunday.