The Ubc Under Gr Adu a Te Journal of English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Growth of VOD Investment in Local Entertainment Industries Contents

Asia-on- demand: the Growth of VOD Investment in Local Entertainment Industries contents Important Notice on Contents – Estimations and Reporting 04 GLOSSARY This report has been prepared by AlphaBeta for Netflix. 08 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY All information in this report is derived or estimated by AlphaBeta analysis using both 13 FACT 1: proprietary and publicly available information. Netflix has not supplied any additional data, nor VOD INVESTMENT IN LOCAL ASIAN CONTENT COULD GROW 3.7X BY 2022 does it endorse any estimates made in the report. Where information has been obtained from third party sources and proprietary sources, this is clearly referenced in the footnotes. 17 FACT 2: STRONG CONSUMER DEMAND INCENTIVIZES INVESTMENT IN HIGH-QUALITY Published in October 2018 LOCAL ENTERTAINMENT ONLINE 23 FACT 3: THROUGH VOD, ORIGINAL CONTENT PRODUCED IN ASIA IS GETTING INCREASED ACCESS TO GLOBAL AUDIENCES 27 FACT 4: THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF LOCAL CONTENT INVESTMENT IS 3X LARGER THAN WHAT VOD PLAYERS SPEND 32 FACT 5: VOD PLAYERS OFFER BENEFITS TO THE LOCAL INDUSTRY - WELL BEYOND LOCAL CONTENT INVESTMENT 38 FACT 6: THE CONTENT PRODUCTION VALUE CHAIN IS BECOMING MORE GLOBAL AND DIVERSE, ALLOWING ASIAN COUNTRIES TO SPECIALIZE 43 FACT 7: THE KEY DRIVERS TO CAPTURING THE VOD CONTENT OPPORTUNITY ARE INVESTMENT INCENTIVES, SUPPORTIVE REGULATION, AND AlphaBeta is a strategy and economic advisory business serving clients across Australia and HIGH-QUALITY INFRASTRUCTURE Asia from offices in Singapore, Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne. 54 FINAL THOUGHTS: IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICYMAKERS SINGAPORE Level 4, 1 Upper Circular Road 57 APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY Singapore, 058400 Tel: +65 6443 6480 Email: [email protected] Web: www.alphabeta.com glossary The following terms have been used at various stages in this report. -

Discurso Y Comunicación

GRUPO TEMÁTICO 14 Discurso y Comunicación 2 El falso documental como supuesto tercer espacio: revisiones críticas a una aritmética cinematográfica Sergio José Aguilar Alcalá 7 La potencia narrativa de los fotolibros Marina Feldhues 13 Estudiar la ideología desde el discurso: Los complejos ideológicos de la Reforma Energética de 2013 en México Axel Velázquez Yáñez 19 La construcción del ethos discursivo del científico en los blogs de divulgación científica brasileños Natália Martins Flores & Isaltina Maria de Azevedo Mello Gomes 26 Jóvenes en Argentina: vulnerabilidad simbólica y mediática Fabiana Martínez 32 “Malvinas entre el reclamo y el olvido: disputas discursivas a 30 años de la guerra” Claudia Guadalupe Grzincich & María Ercilia Alaniz 37 Os personagens de HQs e o consumo de tatuagens Matheus Eurico Noronha & Daniela Cunha Fernandes Miranda 43 El narcotráfico como fenómeno social recreado en el discurso de la prensa en México Édgar Ávila González & Gabriela Sánchez Medina 52 ¿Persona non grata? Las representaciones de Michel Temer en Carta Capital André Mendes & Jonaina Barcelos 59 “El pueblo necesita colaborar”: Un análisis lexicográfico de los discursos de posesión de Michel Temer en 2016 Franco Iacomini Junior & Torcis Prado Junior & Moisés Cardoso 67 Netflix: del procesamiento de la información a la reinterpretación de la cultura Eliseo Colón Zayas 73 3 Discurso hegemónico y contradiscurso: análisis crítico del discurso mediático sobre el conflicto amazónico el “Baguazo”. Franklin Guzmán Zamora 78 Criatividade, poder e inspiração: TED talks e sua retórica desterritorializada Carolina Cavalcanti Falcão 85 Discurso y Comunicación en la historia de la música romántica mexicana Tanius Karam Cárdenas 90 Imágenes de la nación y nuevo populismo político-mediático entre Brasil y Perú: una mirada semiótico-discursiva Paolo Demuru & Elder Cuevas-Calderón 95 Géneros, tradiciones discursivas y tecnologías. -

"Being in the Wrong Place at the Wrong Time

“Being in the wrong place at the wrong time” Ethnographic insights into experiences of incarceration and release from a Mexican prison A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2013 Carolina Corral Paredes School of Social Sciences Department of Social Anthropology Contents List of figures 4 Abstract 5 Declaration 6 Copyright Statement 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction 9 Narratives of incarceration 11 Individual trajectories and lived experiences 14 The “war on drugs”: research and lived experience 15 Modes of representation 19 From peace to imprisonment 21 Imprisonment as a stage in life 23 Methods and access to prison 26 Chapter 1: Economic and social everyday in prison 43 Ethnography of the job market in prison 45 The “Top Ladies”: charisma, privileges and wealth 48 Extortion and owning a business 51 Consuelo, a Colombian prisoner 53 Regaining status through hard work 56 Chapter 2: Narratives of self 62 Legal arguments 65 Gendered stories in a grey room 69 ‘Reflections’ by La Enamorada. 79 La Enamorada after prison 91 Chapter 3: The gaze and morality 95 Introduction: vision and exposure 95 Women’s Day ceremony 98 Visiting the men’s prison 101 Secrecy and power 106 Theatrocracy amends the programme 109 Chapter 4 Uncertainty in prison 115 The uncertainty of prison time 119 Uncertainty as an emotional atmosphere 124 Coping with uncertainty 126 Chapter 5: Time will Tell [film, 52’] 138 Chapter 6: Making “Time will tell” 139 Filming with Sandra 143 Filming with Reynaldo 147 2 Filming with David 151 A finished film, unfinished lives. -

The 15Th International Gothic Association Conference A

The 15th International Gothic Association Conference Lewis University, Romeoville, Illinois July 30 - August 2, 2019 Speakers, Abstracts, and Biographies A NICOLE ACETO “Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut”: The Terror of Domestic Femininity in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House Abstract From the beginning of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, ordinary domestic spaces are inextricably tied with insanity. In describing the setting for her haunted house novel, she makes the audience aware that every part of the house conforms to the ideal of the conservative American home: walls are described as upright, and “doors [are] sensibly shut” (my emphasis). This opening paragraph ensures that the audience visualizes a house much like their own, despite the description of the house as “not sane.” The equation of the story with conventional American families is extended through Jackson’s main character of Eleanor, the obedient daughter, and main antagonist Hugh Crain, the tyrannical patriarch who guards the house and the movement of the heroine within its walls, much like traditional British gothic novels. Using Freud’s theory of the uncanny to explain Eleanor’s relationship with Hill House, as well as Anne Radcliffe’s conception of terror as a stimulating emotion, I will explore the ways in which Eleanor is both drawn to and repelled by Hill House, and, by extension, confinement within traditional domestic roles. This combination of emotions makes her the perfect victim of Hugh Crain’s prisonlike home, eventually entrapping her within its walls. I argue that Jackson is commenting on the restriction of women within domestic roles, and the insanity that ensues when women accept this restriction. -

Self-Management for Actors 4Th Ed

This is awesome Self-Management for Actors 4th ed. bonus content by Bonnie Gillespie. © 2018, all rights reserved. SMFA Shows Casting in Major Markets Please see page 92 (the chapter on Targeting Buyers) in the 4th edition of Self-Management for Actors: Getting Down to (Show) Business for detailed instructions on how best to utilize this data as you target specific television series to get to your next tier. Remember to take into consideration issues of your work papers in foreign markets, your status as a local hire in other states, and—of course—check out the actors playing characters at your adjacent tier (that means, not the series regulars 'til you're knocking on that door). After this mega list is a collection of resources to help you stay on top of these mainstream small screen series and pilots, so please scroll all the way down. And of course, you can toss out the #SMFAninjas hashtag on social media to get feedback on your targeting strategy. What follows is a list of shows actively casting or on order for 4th quarter 2018. This list is updated regularly at the Self-Management for Actors website and in the SMFA Essentials mini- course on Show Targeting. Enjoy! Show Title Show Type Network 25 pilot CBS #FASHIONVICTIM hour pilot E! 100, THE hour CW 13 REASONS WHY hour Netflix 3 BELOW animated Netflix 50 CENTRAL half-hour A&E 68 WHISKEY hour pilot Paramount Network 9-1-1 hour FOX A GIRL, THE half-hour pilot A MIDNIGHT KISS telefilm Hallmark A MILLION LITTLE THINGS hour ABC ABBY HATCHER, FUZZLY animated Nickelodeon CATCHER ABBY'S half-hour NBC ACT, THE hour Hulu ADAM RUINS EVERYTHING half-hour TruTV ADVENTURES OF VELVET half-hour PROZAC, THE ADVERSARIES hour pilot NBC AFFAIR, THE hour Showtime AFTER AFTER PARTY new media Facebook AFTER LIFE half-hour Netflix AGAIN hour Netflix For updates to this doc, quarterly phone calls, convos at our ninja message boards, and other support, visit smfa4.com. -

The 15Th International Gothic Association Conference Lewis University, Romeoville, Illinois July 30 - August 2, 2019

The 15th International Gothic Association Conference Lewis University, Romeoville, Illinois July 30 - August 2, 2019 Monday, July 29 Pre-scheduled shuttles from Midway, O’Hare airports to the Aloft hotel, campus: times to be announced Registration for those staying on campus, Mother Teresa Hall: times to be announced Dinner for those staying on campus: 5:00 – 6:30 p.m., Academic Building (Charlie’s Place) Graduate Student Meetup: 6:30 – 8:30 p.m., Gazebo or to be announced Tuesday, July 30 One-time morning shuttle from Midway, O’Hare airports to the Aloft hotel, campus: time to be announced Registration: 8:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m., Academic Building (AS 150A) Graduate Student Workshop, Turning a Negative into a Positive: 10:30 – 11:30 a.m., Academic Building (AS 158A) 1. Rebecca Duncan, University of Stirling 2. Karen Macfarlane, Mount Saint Vincent University 3. Justin D. Edwards, University of Stirling 4. Xavier Aldana Reyes, Manchester Metropolitan University 5. Enrique Ajuria Ibarra, Universidad de las Américas Puebla Lunch (provided), St. Charles Borromeo (Flight Deck): 12:00 – 1:15 p.m. Welcoming remarks, St. Charles Borromeo (Convocation Hall): 1:30 – 2:15 p.m. David Livingston, President, Lewis University Jamil Mustafa, Lewis University Session 1: 2:30 – 4:00 p.m., Academic Building Classrooms Panel 1a (AS 113S): Frankenstein Chair: Daniel Kasper 1. From Horror to Terror: American Transmediations of Frankenstein – Colleen Karn, Methodist College 2. Beyond the Wound: Transgenerational Trauma Transmission in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein – Anne Mahler, University College Cork 3. Death Embodied: Ecogothic Interventions in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein – Bryan McMillan, University of North Carolina Greensboro 1 Panel 1b (AS 018S): Gothic Chapbooks and Prefaces Chair: Hannah-Freya Blake 1. -

Mexican Melodrama in the Age of Netflix: Algorithms for Cultural

Mexican Melodrama in the Age of Netflix: Algorithms for Cultural Proximity Melodrama mexicano en la era de Netflix: ELIA MARGARITA algoritmos para la proximidad cultural CORNELIO-MARÍ1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2020.7481 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5495-1870 By using algorithms to track the data of their users in Mexico, Netflix has managed to solve the equation of cultural proximity. Since 2015 it has produced original series that include melodramatic traits, even if they align with genres like comedy, biopic and political thriller. Applying industrial and textual analysis, this article argues that Netflix has established a love-hate relationship with Mexican melodrama, making fun of its conventions but using them nevertheless. It concludes that algorithms have the potential to transform Internet TV providers into competitors for local producers. KEYWORDS: Netflix, InternetTV , algorithms, melodrama, cultural proximity, telenovela. Netflix ha resuelto la ecuación de la proximidad cultural en México utilizando algoritmos para monitorear los datos de sus usuarios. Desde 2015 ha producido series originales que muestran rasgos melodramáticos a pesar de pertenecer a géneros como la comedia, la biografía o la acción de trasfondo político. Con base en un análisis textual y de la in- dustria, este artículo sostiene que Netflix ha establecido una relación de amor-odio con el melodrama mexicano, burlándose de sus convenciones pero usándolas al mismo tiempo. Se concluye que el uso de algoritmos tiene el potencial de transformar a los proveedores de televisión por Internet en competidores de los productores locales. PALABRAS CLAVE: Netflix, televisión por Internet, algoritmos, melodrama, proximidad cultural, telenovela. -

Shooting in Spain 2021', Where Foreign Competing in International Investors Will Find Information About Markets

2021 2021 The audiovisual industry is To follow these strategic objectives A publication that highlights the strategic for the Spanish and with a view to develop the importance of consolidating the government due to its global aforementioned Audiovisual Hub, the international markets in which the nature, its capacity to generate Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism Spanish audiovisual industry is employment and its potential will continue working to strengthen already present and the new markets for modernisation thanks to the Spanish audiovisual industry where opportunities may open up. digitalization. That is why we and improve Spain's conditions as a launched the 'Spain, Audiovisual destination for international filming. These words in presenting the guide Hub of Europe' plan last March, A task in which the companies in the serve to express the commitment of with more than EUR 1.6 billion industry have always provided their the Ministry of Industry, Trade and in public investment until cooperation, along with the Spain Film Tourism to the Spanish audiovisual 2025, with the aim of turning Commission. These are key partners to industry, as one of the priority vectors Spain into a leading country consolidate the audiovisual industry's of the government's actions, and in audiovisual production in activity inside and outside Spain. in view of the economic recovery María Reyes Maroto Illera the digital era, a magnet for and development of the audiovisual international investment and As a result of this collaboration, we industry. Minister for Industry, Trade and Tourism talent, and with a reinforced put together the guide 'Who is Who. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

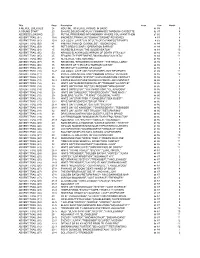

A Merge Emerges 24 Routine to Merge Progs. in Basic 5 A

Title Page Description Issue Year Month A MERGE EMERGES 24 ROUTINE TO MERGE PROGS. IN BASIC 61 88 5 A SOUND START 20 Q+A.RE.SOUND AND PLAY COMMANDS THROUGH CASSETTE 52 87 8 ADDRESS LOADING 23 PUT ML PROGRAMS INTO MEMORY WHERE YOU WANT THEM 27 85 7 ADVENT.TRAIL (01) 15-8 MADNESS,"FRANKLIN","BONKA","DRONE" REVIEWED 4 83 8 ADVENT.TRAIL (01) 15-8 COLOSSAL CAVE,"CALIXTO","R.OF DARKNESS"REVWED 4 83 8 ADVENT.TRAIL (02) 41 PIMANIA,"RING OF DARKNESS","TOUCHSTONE" 16 84 8 ADVENT.TRAIL (03) 45 PETTIGREW'S DIARY,"OPERATION SAFRAS" 17 84 9 ADVENT.TRAIL (04) 45 INCREDIBLE HULK,"THE GOLDEN BATON" 18 84 10 ADVENT.TRAIL (05) 50 ARNOLD BLACKWOOD,"ARROW OF DEATH (PTS.1&2)" 20 84 12 ADVENT.TRAIL (05) 45 FEASIBILITY EXPERIMENT,"WAXWORKS","CALIXTO" 19 84 11 ADVENT.TRAIL (06) 43 REVIEWED-"TIME MACHINE" 21 85 1 ADVENT.TRAIL (07) 35 REVIEWED-"SHRUNKEN SCIENTIST","THE SKULL LORD" 23 85 3 ADVENT.TRAIL (08) 35 REVIEWS OF "CIRCUS"&"HORROR CASTLE" 24 85 4 ADVENT.TRAIL (09) 29 REVIEW OF "CAVERNS OF DOOM" 26 85 6 ADVENT.TRAIL (10) 36-7 COLOSSAL CAVE AND "ADVENTURELAND" REVIEWED 31 85 11 ADVENT.TRAIL (11) 35 PIRATE ADVENTURE AND "VOODOO CASTLE" REVIEWS 32 85 12 ADVENT.TRAIL (12) 26 SECRET MISSION,"SYZYGY"HELP+ADVENTURE CONTACT 33 86 1 ADVENT.TRAIL (13) 32-4 CASTLE BLACKSTAR&"SAM BUICK"REVD.+ADV.CONTACT 34 86 2 ADVENT.TRAIL (14) 29- HINTS ON "MADNESS/MINOTAUR","TRKBOER",LOINSPCE" 35 86 3 ADVENT.TRAIL (14) 29- HINTS ON "FRANKLINS","SEC.MISSION","WINGS/WAR" 35 86 3 ADVENT.TRAIL (14) 29- HINTS ON"SYZYGY","JUXTAPOSITION","ICE KINGDOM" 35 86 3 ADVENT.TRAIL (14) 29- HINTS ON -

![Produção De Sentido Na Cultura Midiatizada [Recurso Eletrônico] / Organizadores: Laan Mendes De Barros, José Carlos Marques, P964 Ana Silvia Médola](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2528/produ%C3%A7%C3%A3o-de-sentido-na-cultura-midiatizada-recurso-eletr%C3%B4nico-organizadores-laan-mendes-de-barros-jos%C3%A9-carlos-marques-p964-ana-silvia-m%C3%A9dola-6542528.webp)

Produção De Sentido Na Cultura Midiatizada [Recurso Eletrônico] / Organizadores: Laan Mendes De Barros, José Carlos Marques, P964 Ana Silvia Médola

~ PRODUÇAO DE SENTIDO NA CULTURA MIDIATIZADA Laan Mendes de Barros José Carlos Marques Ana Silvia Médola (Organizadores) s i sa r e v s n a r { olhares t ~ PRODUÇAO DE SENTIDO NA CULTURA MIDIATIZADA Laan Mendes de Barros José Carlos Marques Ana Silvia Médola (Organizadores) s i sa r e v s n a r { olhares t UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS Reitora: Sandra Regina Goulart Almeida Vice-Reitor: Alessandro Fernandes Moreira FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS Diretor: Bruno Pinheiro Wanderley Reis Vice-Diretora: Thais Porlan de Oliveira PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO Coordenador: Bruno Souza Leal Sub-Coordenador: Carlos Frederico de Brito D’Andréa SELO EDITORIAL PPGCOM Carlos Magno Camargos Mendonça Nísio Teixeira CONSELHO CIENTÍFICO Ana Carolina Escosteguy (PUC-RS) Kati Caetano (UTP) Benjamim Picado (UFF) Luis Mauro Sá Martino (Casper Líbero) Cezar Migliorin (UFF) Marcel Vieira (UFPB) Elizabeth Duarte (UFSM) Mariana Baltar (UFF) Eneus Trindade (USP) Mônica Ferrari Nunes (ESPM) Fátima Regis (UERJ) Mozahir Salomão (PUC-MG) Fernando Gonçalves (UERJ) Nilda Jacks (UFRGS) Frederico Tavares (UFOP) Renato Pucci (UAM) Iluska Coutinho (UFJF) Rosana Soares (USP) Itania Gomes (UFBA) Rudimar Baldissera (UFRGS) Jorge Cardoso (UFRB | UFBA) www.seloppgcom.fafich.ufmg.br Avenida Presidente Antônio Carlos, 6627, sala 4234, 4º andar Pampulha, Belo Horizonte - MG. CEP: 31270-901 Telefone: (31) 3409-5072 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) (eDOC BRASIL, Belo Horizonte/MG) Produção de sentido na cultura midiatizada [recurso eletrônico] / Organizadores: Laan Mendes de Barros, José Carlos Marques, P964 Ana Silvia Médola. - Belo Horizonte, MG: Fafich/Selo PPGCOM/ UFMG, 2020. 412p. Formato: PDF Requisitos de sistema: Adobe Acrobat Reader Modo de acesso: World Wide Web Inclui bibliografia ISBN 978-65-86963-21-2 1. -

Production Notes

Production Notes INTRODUCTION BY FERNANDA MELCHOR “Somos.” is a fictional story based on the investigative report “How the U.S. Triggered a Massacre in Mexico,” written by acclaimed American journalist Ginger Thompson. Her exceptional piece incorporates the stories and testimonies of dozens of people who experienced first-hand the events of March 2011 in Allende, Coahuila, a small community near the U.S. border. “Somos.” is the first TV production to recount the event from the victims’ perspective. It centers around the experience of violence in a small community in the context of rural life — a subject that’s rarely been explored on Mexican screens before. “Somos.” was created by James Schamus, who also co-wrote the series with Mexican writers Monika Revilla and me, Fernanda Melchor. The resulting screenplay exposes the tragic and horrific aftermath of drug trafficking in a small town in northern Mexico. It features interlocking storylines with multiple protagonists, each at the center of their own universe. They all go about their lives, unaware of their imminent death sentence or reprieve. After reading Thompson's oral history, filmmaker James Schamus was struck by the complex story surrounding these events and the fact that the tragedy was not more widely known. He immediately started reflecting on ways the story could be told through a different narrative — one centered on the experience of the victims. “I immediately took it as a challenge,” said Schamus, “to reframe real people’s lived experiences in a distinct work — a fictional narrative that would break away from the usual genres that so compellingly mediate our understanding of how violence structures so much of our ‘day-to-day living,’ regardless of how close or distant that violence is from us.” The idea was not to focus solely on how drug trafficking affects the lives of ordinary people in Mexico, but to construct a multiple narrative that would serve as a real discourse on the various forms of violence (institutional, physical, sexual, gender-based, domestic, etc.) that characterize modern life.