Introduction to Documentary Door Bill Nichols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Film by Chris Hegedus and D a Pennebaker

a film by Chris Hegedus and D A Pennebaker 84 minutes, 2010 National Media Contact Julia Pacetti JMP Verdant Communications [email protected] (917) 584-7846 FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] PRAISE FOR KINGS OF PASTRY “The film builds in interest and intrigue as it goes along…You’ll be surprised by how devastating the collapse of a chocolate tower can be.” –Mike Hale, The New York Times Critic’s Pick! “Alluring, irresistible…Everything these men make…looks so mouth-watering that no one should dare watch this film on even a half-empty stomach.” – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times “As the helmers observe the mental, physical and emotional toll the competition exacts on the contestants and their families, the film becomes gripping, even for non-foodies…As their calm camera glides over the chefs' almost-too-beautiful-to-eat creations, viewers share their awe.” – Alissa Simon, Variety “How sweet it is!...Call it the ultimate sugar high.” – VA Musetto, The New York Post “Gripping” – Jay Weston, The Huffington Post “Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker turn to the highest levels of professional cooking in Kings of Pastry,” a short work whose drama plays like a higher-stakes version of popular cuisine-oriented reality TV shows.” – John DeFore, The Hollywood Reporter “A delectable new documentary…spellbinding demonstrations of pastry-making brilliance, high drama and even light moments of humor.” – Monica Eng, The Chicago Tribune “More substantial than any TV food show…the antidote to Gordon Ramsay.” – Andrea Gronvall, Chicago Reader “This doc is a demonstration that the basics, when done by masters, can be very tasty.” - Hank Sartin, Time Out Chicago “Chris Hegedus and D.A. -

Monterey Pop Festival: Otis Redding / Jimi Hendrix

Der folgende Text erschien zuerst in: Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung 5.4, 2010, S. 501 - 505. Er findet sich nun auch im „Archiv der Rockumentaries“ der Zeitschrift Rock and Pop in the Movies: Ein Journal zur Analyse von Rock- und Popmusikfilmen. ZWEI NACHTRÄGE ZUM MONTEREY POP FESTIVAL: OTIS REDDING / JIMI HENDRIX Claus Tieber Rund 20 Jahre nach MONTEREY POP [1] machten D.A. Pennebaker und Chris Hegedus aus dem 1968 gedrehten Material zwei weitere Filme, in deren Mittelpunkt die Auftritte von Otis Redding und Jimi Hendrix stehen. Beide Shows sind vollständig dokumentiert, die Filme dauern 19 (Redding) bzw. 49 Minuten (Hendrix) und werden sowohl aus inhaltlichen wie aus pragmatischen Gründen zumeist gemeinsam gezeigt. Die beiden Shows heben sich aus unterschiedlichen Gründen vom Rest des Festivals ab – und das nicht nur, weil Redding und Hendrix die beiden einzigen afro-amerikanischen Musiker des Festivals waren. Beide Filme sind in der DVD-Box The Complete Monterey Pop Festival der Criterion Collection (Ausg. 167) enthalten (3 DVDs, USA 2002, kein Regional-Code). SHAKE! OTIS AT MONTEREY USA 1989 R: Don A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, David Dawkins. P: Alan Douglas. K: Nick Doob, Barry Feinstein, Richard Leacock, Albert Maysles, Roger Murphy, D.A. Pennebaker, Nicholas T. Proferes. T (Re-Recording): Dominick Tavella. Musiker: Otis Redding with Booker T. and the MGs and the Markeys (Booker T. Jones: org., Steve Cropper: git., Donald "Duck" Dunn: b, Al Jackson Jr.: dr., perc.; Wayne Jackson: tr, Joe Arnold; t-sax, Andrew Love b-sax). 19min. 35mm, 1,33:1. Farbe. Songs: Shake, Respect, I’ve been loving you too long, Satisfaction, Try a Little Tenderness. -

An Exploration of the Potential of Participatory Documentary Filmmaking in Rural India

Village Tales: an exploration of the potential of participatory documentary filmmaking in rural India Sue Sudbury A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bournemouth University January 2015 Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 2 A practice-led Phd This practice-led PhD follows the regulations as set out in Bournemouth University’s Code of Practice for Research Degrees. It consists of a 45 minute documentary film and an accompanying 29,390 word exegesis: ‘The exegesis should set the practice in context and should evaluate the contribution that the research makes to the advancement of the research area. The exegesis must be of an appropriate proportion of the submission and would normally be no less than 20,000 words or the equivalent…A full appreciation of the originality of the work and its contribution to new knowledge should only be possible through reference to both’. Extract from Code of Practice for Research Degrees, Bournemouth University, September 2014. A note on terminology The term ‘documentary’ refers to my own film informed by the documentary tradition in British film and television. ‘Ethnographic film’ refers to research-based filmmaking, often undertaken by visual anthropologists and/or ethnographers, and that research has also informed my own practice as a documentary filmmaker. -

From Del Ray to Monterey Pop Festival

Office of Historic Alexandria City of Alexandria, Virginia Out of the Attic From Del Ray to Monterey Pop Festival Alexandria Times, February 11, 2016 Image: The Momas and the Popas. Photo, Office of Historic Alexandria. t the center of Alexandria’s connection to rock and folk music fame was John Phillips. Born in South A Carolina, John and his family lived in Del Ray for much of his childhood. He attended George Washington High School, like Cass Elliot and Jim Morrison, graduating in 1953. He met and then married his high school sweetheart, Susie Adams, with whom he had two children, Jeffrey and Mackenzie, who later became famous in her own right. Phillips and Adams lived in the Belle Haven area after high school, but John left his young family at their Fairfax County home to start a folk music group called the Journeymen in New York City. The new group included lifelong friend and collaborator Philip Bondheim, later known as Scott McKenzie, also from Del Ray. The young men had met through their mothers, who were close friends. While in New York, John’s romantic interests turned elsewhere and he told Susie he would not be returning to her. Soon after, he married his second wife, Michelle Gilliam, who was barely out of her teens. They had one daughter, Chynna, who also gained fame as a singer. Gilliam and Phillips joined two former members of a group called the Mugwumps, Denny Doherty and Cass Elliot to form The Mamas and the Papas in 1965. This photo from that time shows Gilliam and Doherty to the left, Phillips and Elliot to the right, and fellow Alexandrian Bondheim at the center. -

Towards a Fifth Cinema

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Towards a fifth cinema Article (Accepted Version) Kaur, Raminder and Grassilli, Mariagiulia (2019) Towards a fifth cinema. Third Text, 33 (1). pp. 1- 25. ISSN 0952-8822 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/80318/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Towards a Fifth Cinema Raminder Kaur and Mariagiulia Grassilli Third Text article, 2018 INSERT FIGURE 1 at start of article I met a wonderful Nigerian Ph.D. -

Reversing the Gaze When (Re) Presenting Refugees in Nonfiction Film

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA ARTS (2020) Vol. 5, Nº. 2 pp. 82-99 © 2020 BY-NC-ND ijfma.ulusofona.pt doi: 10.24140/ijfma.v5.n2.05 TOWARDS A PARTICIPATORY APPROACH: REVERSING THE GAZE WHEN (RE) PRESENTING REFUGEES IN NONFICTION FILM RAND BEIRUTY* * Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF (Germany) 82 TOWARDS A PARTICIPATORY APPROACH RAND BEIRUTY Rand Beiruty is currently pursuing a practice-based Ph.D. at Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF. She is alumna of Berlinale Talents, Beirut Talents, Film Leader Incubator Asia, Documentary Campus, Locarno Documentary School and Ji.hlava Academy. Corresponding author Rand Beiruty [email protected] Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF Marlene-Dietrich-Allee 11, 14482 Potsdam Germany Paper submitted: 24th march 2020 Accepted for Publication: 26th September 2020 Published Online: 13th November 2020 83 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA ARTS (2020) Vol. 5, Nº. 2 Abstract Living in Germany during the peak of the “refugee crisis”, I was bombarded with constant reporting on the topic that clearly put forth a problematic representation of refugees, contributing to rendering them a ‘problem’ and the situation a ‘crisis’. This reflects in my own film practice in which I am frequently engaging with Syrian refugees as protagonists. Our shared language and culture made it easier for us to form a connection. However, as a young filmmaker, I felt challenged and conflicted by the complexities of the ethics of representation, especially when making a film with someone who’s going through a complex insti- tutionalized process. In this paper I explore how reflecting on my position within the filmmaking process affected my relationship with my film par- ticipants and how this reflection influenced my choice of documentary film form. -

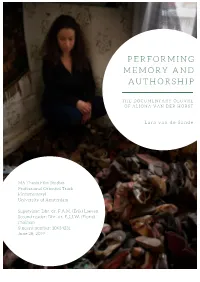

Performing Memory and Authorship

P E R F O R M I N G M E M O R Y A N D A U T H O R S H I P T H E D O C U M E N T A R Y O E U V R E O F A L I O N A V A N D E R H O R S T L a r a v a n d e S a n d e MA Thesis Film Studies Professional Oriented Track (Documentary) University of Amsterdam Supervisor: Dhr. dr. F.A.M. (Erik) Laeven Second reader: Dhr. dr. F.J.J.W. (Floris) Paalman Student number: 10634231 June 28, 2019 For my father Rien van de Sande (1947-2016) 2 Ugliness is beauty that cannot be contained within the soul. It is the transformational force of poetry or imagery, that is what you are looking for as a filmmaker, or an artist. Aliona van der Horst 3 Contents Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………...……7 Chapter 1: The rise of subjective documentary filmmaking…………………………………12 1.1 Origins: a cinema of auteurs……………………………………………………….12 1.2 The start of female documentary authorship ………………..............................14 1.3 Defining the practice: a mode instead of a genre…………………………………..17 Chapter 2: Memory, emotion & narrative…………………………………………………...20 2.1 Cognitive frameworks: narrative, emotion and memory ………………………….20 2.2 Media and memory: remembering (without) experience…………….....................22 2.3 Memory is mediated…………………………………………………..................24 2.4 Prosthetic memory: the artificial limb made of imagined memories………...….…..25 2.5 The filmic translation of personal memory………………………………………26 Chapter 3: Turning memory into narrative in Voices of Bam……………………………...…28 3.1 Voices of Bam’s narrative of experience: wandering through the rubble……………28 3.2 The inner voices talking: active remembering in direct address…………….……. -

On the Road with Janis Joplin Online

6Wgt8 (Download) On the Road with Janis Joplin Online [6Wgt8.ebook] On the Road with Janis Joplin Pdf Free John Byrne Cooke *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #893672 in Books John Byrne Cooke 2015-11-03 2015-11-03Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.25 x .93 x 5.43l, 1.00 #File Name: 0425274128448 pagesOn the Road with Janis Joplin | File size: 33.Mb John Byrne Cooke : On the Road with Janis Joplin before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised On the Road with Janis Joplin: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. A Must Read!!By marieatwellI have read all but maybe 2 books on the late Janis Joplin..by far this is one of the Best I have read..it showed the "music" side of Janis,along with the "personal" side..great book..Highly Recommended,when you finish this book you feel like you've lost a band mate..and a friend..she could have accomplished so much in the studio,such as producing her own records etc..This book is excellent..0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.By Mic DAs a teen in 1969 and growing up listening to Janis and all the bands of the 60's and 70's, this book was very enjoyable to read.If you ever wondered what it might be like to be a road manager for Janis Joplin, John Byrne Cooke answers it all.Those were extra special days for all of us and John's descriptions of his experiences, helps to bring back our memories.Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. -

Copyright by Leah Michelle Ross 2012

Copyright by Leah Michelle Ross 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Leah Michelle Ross Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A Rhetoric of Instrumentality: Documentary Film in the Landscape of Public Memory Committee: Katherine Arens, Supervisor Barry Brummett, Co-Supervisor Richard Cherwitz Dana Cloud Andrew Garrison A Rhetoric of Instrumentality: Documentary Film in the Landscape of Public Memory by Leah Michelle Ross, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2012 Dedication For Chaim Silberstrom, who taught me to choose life. Acknowledgements This dissertation was conceived with insurmountable help from Dr. Katherine Arens, who has been my champion in both my academic work as well as in my personal growth and development for the last ten years. This kind of support and mentorship is rare and I can only hope to embody the same generosity when I am in the position to do so. I am forever indebted. Also to William Russell Hart, who taught me about strength in the process of recovery. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee members: Dr Barry Brummett for his patience through the years and maintaining a discipline of cool; Dr Dana Cloud for her inspiring and invaluable and tireless work on social justice issues, as well as her invaluable academic support in the early years of my graduate studies; Dr. Rick Cherwitz whose mentorship program provides practical skills and support to otherwise marginalized students is an invaluable contribution to the life of our university and world as a whole; Andrew Garrison for teaching me the craft I continue to practice and continuing to support me when I reach out with questions of my professional and creative goals; an inspiration in his ability to juggle filmmaking, teaching, and family and continued dedication to community based filmmaking programs. -

Introduction

CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction This book consists of edited conversations between DP’s, Gaffer’s, their crew and equipment suppliers. As such it doesn’t have the same structure as a “normal” film reference book. Our aim is to promote the free exchange of ideas among fellow professionals, the cinematographer, their camera crew, manufacturer's, rental houses and related businesses. Kodak, Arri, Aaton, Panavision, Otto Nemenz, Clairmont, Optex, VFG, Schneider, Tiffen, Fuji, Panasonic, Thomson, K5600, BandPro, Lighttools, Cooke, Plus8, SLF, Atlab and Fujinon are among the companies represented. As we have grown, we have added lists for HD, AC's, Lighting, Post etc. expanding on the original professional cinematography list started in 1996. We started with one list and 70 members in 1996, we now have, In addition to the original list aimed soley at professional cameramen, lists for assistant cameramen, docco’s, indies, video and basic cinematography. These have memberships varying from around 1,200 to over 2,500 each. These pages cover the period November 1996 to November 2001. Join us and help expand the shared knowledge:- www.cinematography.net CML – The first 5 Years…………………………. Page 1 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Page 2 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction................................................................ 1 Shooting at 25FPS in a 60Hz Environment.............. 7 Shooting at 30 FPS................................................... 17 3D Moving Stills...................................................... -

BEDLAM a Film by by Kenneth Paul Rosenberg

BEDLAM A film by by Kenneth Paul Rosenberg Trailer: https://vimeo.com/312148944 Run Time: 84:53 Website: www.bedlamfilm.com Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/BedlamTheFilm/ Twitter: @bedlamfilm Film stills: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1GuefJBcR5Eh4ILE8v_t6Wv9xZngWfvJE?usp=sh aring Poster: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1D46P8faWmvc06YAs5Vq3L1vm6_9NHf-C/view?usp=s haring PRESS CONTACT: DKC News Joe DePlasco & Jordan Lawrence [email protected] EDUCATIONAL SALES: Ro*Co Films Allie Silvestry [email protected] BOOK SALES AND PRESS: Avery, Penguin Random House Casey Maloney [email protected] FILM SYNOPSIS BEDLAM is a feature-length documentary that addresses the national crisis and criminalization of the mentally ill, its connection between hundreds of thousands of homeless Americans and our nation’s disastrous approach to caring for its psychiatric patients. In the wake of decades of de-institutionalization in which half a million psychiatric hospital beds have been lost, our jails and prisons have become America’s largest mental institutions. Emergency rooms provide the only refuge for severely mentally ill who need care. Psychiatric patients are held captive and warehoused in overcrowded jails as untrained and under-equipped first-responders are on the front lines. At least half the people shot and killed by police each year have mental health problems, with communities of color disproportionately impacted. The mentally ill take to the streets for survival, existing in encampments under our freeways and along our streets, doing whatever it takes to stay alive. This crisis can no longer be ignored. Through intimate stories of patients, families, and medical providers, BEDLAM immerses us in the national crisis surrounding care of the severely mentally ill. -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460