Statens Helsetilsyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Permo-Carboniferous Oslo Rift Through Six Stages and 65 Million Years

52 by Bjørn T. Larsen1, Snorre Olaussen2, Bjørn Sundvoll3, and Michel Heeremans4 The Permo-Carboniferous Oslo Rift through six stages and 65 million years 1 Det Norske Oljeselskp ASA, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Eni Norge AS. E-mail: [email protected] 3 NHM, UiO. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Inst. for Geofag, UiO. E-mail: [email protected] The Oslo Rift is the northernmost part of the Rotliegen- des basin system in Europe. The rift was formed by lithospheric stretching north of the Tornquist fault sys- tem and is related tectonically and in time to the last phase of the Variscan orogeny. The main graben form- ing period in the Oslo Region began in Late Carbonif- erous, culminating some 20–30 Ma later with extensive volcanism and rifting, and later with uplift and emplacement of major batholiths. It ended with a final termination of intrusions in the Early Triassic, some 65 Ma after the tectonic and magmatic onset. We divide the geological development of the rift into six stages. Sediments, even with marine incursions occur exclusively during the forerunner to rifting. The mag- matic products in the Oslo Rift vary in composition and are unevenly distributed through the six stages along the length of the structure. Introduction The Oslo Palaeorift (Figure 1) contributed to the onset of a pro- longed period of extensional faulting and volcanism in NW Europe, which lasted throughout the Late Palaeozoic and the Mesozoic eras. Widespread rifting and magmatism developed north of the foreland of the Variscan Orogen during the latest Carboniferous and contin- ued in some of the areas, like the Oslo Rift, all through the Permian period. -

Agenda 2030 in Asker

Agenda 2030 in Asker Voluntary local review 2021 Content Opening Statement by mayor Lene Conradi ....................................4 Highlights........................................................................................5 Introduction ....................................................................................6 Methodology and process for implementing the SDGs ...................8 Incorporation of the Sustainable Development Goals in local and regional frameworks ........................................................8 Institutional mechanisms for sustainable governance ....................... 11 Practical examples ........................................................................20 Sustainability pilots .........................................................................20 FutureBuilt, a collaboration for sustainable buildings and arenas .......20 Model projects in Asker ...................................................................20 Citizenship – evolving as a co-creation municipality ..........................24 Democratic innovation.....................................................................24 Arenas for co-creation and community work ....................................24 Policy and enabling environment ..................................................26 Engagement with the national government on SDG implementation ...26 Cooperation across municipalities and regions ................................26 Creating ownership of the Sustainable Development Goals and the VLR .......................................................................... -

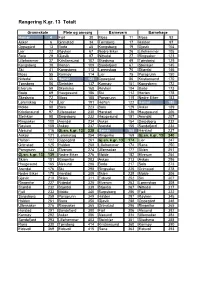

Rangering K.Gr. 13 Totalt

Rangering K.gr. 13 Totalt Grunnskole Pleie og omsorg Barnevern Barnehage Hamar 4 Fjell 30 Moss 11 Moss 92 Asker 6 Grimstad 34 Tønsberg 17 Halden 97 Oppegård 13 Bodø 45 Kongsberg 19 Gjøvik 104 Lier 22 Røyken 67 Nedre Eiker 26 Lillehammer 105 Sola 29 Gjøvik 97 Nittedal 27 Ringsaker 123 Lillehammer 37 Kristiansund 107 Skedsmo 49 Tønsberg 129 Kongsberg 38 Horten 109 Sandefjord 67 Steinkjer 145 Ski 41 Kongsberg 113 Lørenskog 70 Stjørdal 146 Moss 55 Karmøy 114 Lier 75 Porsgrunn 150 Nittedal 55 Hamar 123 Oppegård 86 Kristiansund 170 Tønsberg 56 Steinkjer 137 Karmøy 101 Kongsberg 172 Elverum 59 Skedsmo 168 Røyken 104 Bodø 173 Bodø 69 Haugesund 186 Ski 112 Horten 178 Skedsmo 72 Moss 188 Porsgrunn 115 Nedre Eiker 183 Lørenskog 74 Lier 191 Horten 122 Hamar 185 Molde 88 Sola 223 Sola 129 Asker 189 Kristiansund 97 Ullensaker 230 Harstad 136 Haugesund 206 Steinkjer 98 Sarpsborg 232 Haugesund 151 Arendal 207 Ringsaker 100 Arendal 234 Asker 154 Sarpsborg 232 Røyken 108 Askøy 237 Arendal 155 Sandefjord 234 Ålesund 116 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 238 Hamar 168 Harstad 237 Askøy 121 Lørenskog 254 Ringerike 169 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 240 Horten 122 Oppegård 261 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 174 Lier 247 Grimstad 125 Halden 268 Lillehammer 174 Rana 250 Porsgrunn 133 Elverum 274 Ullensaker 177 Skien 251 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 139 Nedre Eiker 276 Molde 182 Elverum 254 Skien 151 Ringerike 283 Askøy 213 Askøy 256 Haugesund 165 Ålesund 288 Bodø 217 Sola 273 Arendal 176 Ski 298 Ringsaker 225 Grimstad 278 Nedre Eiker 179 Harstad 309 Skien 239 Molde 306 Gjøvik 210 Skien 311 Eidsvoll 252 Ski 307 Ringerike -

Camilla Brautaset 26 Petra Hyncicova 27 Ane Johnsen 28 Jesse Knori 29-30 Anne Siri Lervik 31 Lucy Newman 32-33 Christina Rolandsen 34

Women’s Nordic Camilla Brautaset 26 Petra Hyncicova 27 Ane Johnsen 28 Jesse Knori 29-30 Anne Siri Lervik 31 Lucy Newman 32-33 Christina Rolandsen 34 25 2017 colorado buffaloes Camilla Brautaset A A A 5-5 Senior Women’s Nordic Oslo, Norway (Oslo Handelsgym/Heming Ski Club) 3 Letters; 2014 as a freshman, 2015 as a sophomore, 2016 as a junior Career at Colorado— 2016 (Junior)— An experienced veteran, she enters her senior campaign with 30 races under her belt - the most by any Buffalo on the women’s Nordic team entering the 2017 season. SEASON BY SEASON RESULTS She finished all 10 races through the RMISA Championships and had seven top 20 finishes. 2014 CL FS She placed ninth in the classic race at the RMISA Championships for her top finish of the season in her very last meet. Her top freestyle result was 12th place in the freestyle at New 2M0e1x5ic o(.S Sohpeh womaso ar me)e— mber of the National Collegiate All-Academic Ski Team for maintaining above a 3.5 grade point average and participating at the RMISA Championships/NCAA West Regional. Utah Invitational ̶̶ Montana State Invitational 8 11 She competed and finished 10 events, with four top 20 and two top Colorado Invitational 23 11 2150 1ap4p (eFarreasnhcmesa. Ant) —the New Mexico Invitational, she placed tenth in the 10k classic. She placed eleventh in the 10k classic at the Utah Invitational. She was a member of CU’s 4.0 Club and is N20ew15 Mexico Invitational C45L FS a part of the National All Academic Ski Team. -

Ruter and the Municipality of Bærum Sign Micromobility Contract with TIER

PRESS RELEASE 23 APRIL 2020 Ruter and the Municipality of Bærum sign micromobility contract with TIER TIER has been confirmed as the new supplier of micromobility solutions for the Municipality of Bærum. The municipality’s bike hire scheme will now be expanding to include electric scooters and electric bicycles. Ruter, the Public Transport Authority of Oslo and the former Akershus region, has entered into a public-public collaboration with the Municipality of Bærum. The purpose of the collaboration is to establish a wide range of mobility services for Bærum. The procurement process has now been concluded, with TIER GmbH being selected as the municipality’s supplier of micromobility solutions. – This will be the first time Ruter integrates micromobility solutions into our existing public transport system. Our collaboration with the municipality is working very well, and we believe this is going to be an important step towards the future of mobility services," says Endre Angelvik, director of mobility services at Ruter. The partnership’s plan is to integrate shared e-bikes and e-scooters into the existing public transport system – first in Lysaker, Sandvika and Fornebu in 2020, then in other parts of the municipality during springtime next year. Ruter and the municipality of Bærum intend for the new micromobility scheme to become a valuable and safe addition to the environments where they are introduced. To this end, the partnership will aim to keep in close touch with the municipality’s general population, for purposes of receiving feedback and making adjustments. Formally, the purpose of the contract is to develop a scheme that • complements existing public transport services by allowing travellers seamless movement from transport hubs all the way to their final destination • provides the aforementioned scheme to the city's inhabitants, visitors, businesses and municipal employees – Bærum is on the way towards becoming a climate-smart municipality. -

Rutetabell for Buss Bærum–Oslo

1 Rutetabeller, Bærum – Oslo Gjelder fra 5. juli 2021 • 130 Sandvika -Skøyen • 140 Bekkestua - Østerås - Skøyen • 140E Hosle - Nationaltheatret • 150 Gullhaug - Oslo bussterminal • 150E Gullhaug - Nationaltheatret • 160 Rykkinn -Oslo bussterminal • 160E Rykkinn - Nationaltheatret 2 Sandvika - Skøyen 130 Gyldig fra: 05.07.2021 Mandag - fredag Monday - Friday Sandvika bussterminalEvje Valler skoleLillehagveienPresteveienFossveien DragveienHøvikveienSnoveien KrokvoldenStabekk kinoClausenbakkenTrudvangveienJar skole LillengveienLysaker Skøyen stasjonSkøyen Første first 0519 0521 0522 0524 0525 0526 0528 0530 0531 0532 0534 0535 0536 0537 0538 0541 0544 0547 0534 0536 0537 0539 0540 0541 0543 0545 0546 0547 0549 0550 0551 0552 0553 0556 0559 0602 0549 0551 0552 0554 0555 0556 0558 0600 0601 0602 0604 0605 0606 0607 0608 0611 0614 0617 0604 0606 0607 0609 0610 0611 0613 0615 0616 0617 0619 0620 0621 0622 0623 0626 0629 0632 0619 0621 0622 0624 0625 0626 0628 0630 0631 0632 0634 0635 0636 0637 0638 0641 0644 0647 Fra from 0631 0633 0634 0636 0637 0638 0640 0642 0643 0644 0646 0647 0648 0649 0650 0653 0656 0659 Hvert every 41 43 44 46 47 48 50 52 53 54 56 57 58 59 00 03 06 09 10 min 51 53 54 56 57 58 00 02 03 04 06 07 08 09 10 13 16 19 01 03 04 06 07 08 10 12 13 14 16 17 18 19 20 23 26 29 11 13 14 16 17 18 20 22 23 24 26 27 28 29 30 33 36 39 21 23 24 26 27 28 30 32 33 34 36 37 38 39 40 43 46 49 31 33 34 36 37 38 40 42 43 44 46 47 48 49 50 53 56 59 Til to 0851 0853 0854 0856 0857 0858 0900 0902 0903 0904 0906 0907 0908 0909 0910 0913 0916 0919 -

Welcome to Indra Navia As in Norway

Page 1 February 2018 Contents 1. FLYTOGET, THE AIRPORT EXPRESS TRAIN................................................................................................................................... 1 2. RUTER – PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION IN OSLO AND AKERSHUS ................................................................................................... 2 3. GETTING THE TRAIN TO ASKER................................................................................................................................................... 4 4. HOTEL IN ASKER ......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 5. EATING PLACES IN ASKER ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 6. TAXI ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 7. OSLO VISITOR CENTRE - OFFICIAL TOURIST INFORMATION CENTRE FOR OSLO ........................................................................ 10 8. HOTEL IN OSLO ........................................................................................................................................................................ 11 WELCOME TO INDRA NAVIA AS IN NORWAY 1. Flytoget, the Airport Express Train The Oslo Airport Express Train (Flytoget) -

Rik På Historie - Et Riss Av Kulturhistoriens Fysiske Spor I Bærum

Rik på historie - et riss av kulturhistoriens fysiske spor i Bærum Regulering Natur og Idrett Forord Velkommen til en reise i Bærums rike kulturarv, - fra eldre Det er viktig at vi er bevisst våre kulturhistoriske, arki- steinalder, jernalder, middelalder og frem til i dag. Sporene tektoniske og miljømessige verdier, både av hensyn til vår etter det våre forfedre har skapt finner vi igjen over hele kulturarv og identitet, men også i en helhetlig miljø- og kommunen. Gjennom ”Rik på historie” samles sporene fra ressursforvaltning. vår arv mellom to permer - for å leses og læres. Heftet, som er rikt illustrert med bilder av kjente og mindre Sporene er ofte uerstattelige. Også de omgivelsene som kjente kulturminner og -miljøer, er full av historiske fakta kulturminnene er en del av kan være verdifulle. I Bærum og krydret med små anekdoter. Redaksjonsgruppen, som består kulturminner og kulturmiljøer av om lag 750 eien- består av Anne Sofie Bjørge, Tone Groseth, Ida Haukeland dommer, som helt eller delvis er regulert til bevaring, og av Janbu, Elin Horn, Gro Magnesen og Liv Frøysaa Moe har ca 390 fredete kulturminner. utarbeidet det spennende og innsiktsfulle heftet. I ”Rik på historie” legger forfatterne vekt på å gjenspeile Jeg håper at mange, både unge og eldre, lar seg inspirere til å kommunens særpreg og mangfold. Heftet viser oss hvordan bli med på denne reisen i Bærums rike historie. utviklingen har påvirket utformingen av bygninger og anlegg, og hvordan landskapet rundt oss er endret. Lisbeth Hammer Krog Det som gjør “Rik på historie” særlig interessant er at den er Ordfører i Bærum delt inn i både perioder og temaer. -

Akershus Fortress!

Welcome to Akershus 16 Fortress! 15 17 10 18 19 Experience Akershus with the Fortress Trail. With this 14 11 20 21 22 guide in your hands you can now explore the Fortress on 12 13 your own. Some of the points are marked with QR code, 24 23 giving you exciting stories from the present and past. 9 25 28 8 The trip lasts about 50 minutes at normal walking 7 speed. Enjoy your trip! 27 6 26 1 THE VISITOR CENTRE The Artillery Building, also called the Long Red House, has the date 1774 carved into a stone near the south corner of the foundation wall. Inside the building 5 you can still see the supporting pillars of the curtain wall. The Directorate of Cultural Heritage had its offices here until 1991. Today the building houses the 2 Visitor Centre at Akershus fortress. 30 29 2 THE CARP POND 1 The Carp Pond is part of a big pond that was divided into two when the foun- 31 dations of the northern curtain wall were laid in 1592. The other part served as 4 a moat outside the northern curtain wall. The stream originally came from the 3 area around Christiania Square and ran through this pond and down to Munk’s Pond. The Carp Pond was filled in after the mid-19th century, but recreated in the 1960s. There are carp in the pond in the summer, and a big outdoor stage beside it. 3 THE CROWN PRINCE’S BASTION winch system in the gatehouse. One of the winches is still preserved in the north- in front of and behind the curtain wall. -

Supplementary File for the Paper COVID-19 Among Bartenders And

Supplementary file for the paper COVID-19 among bartenders and waiters before and after pub lockdown By Methi et al., 2021 Supplementary Table A: Overview of local restrictions p. 2-3 Supplementary Figure A: Estimated rates of confirmed COVID-19 for bartenders p. 4 Supplementary Figure B: Estimated rates of confirmed COVID-19 for waiters p. 4 1 Supplementary Table A: Overview of local restrictions by municipality, type of restriction (1 = no local restrictions; 2 = partial ban; 3 = full ban) and week of implementation. Municipalities with no ban (1) was randomly assigned a hypothetical week of implementation (in parentheses) to allow us to use them as a comparison group. Municipality Restriction type Week Aremark 1 (46) Asker 3 46 Aurskog-Høland 2 46 Bergen 2 45 Bærum 3 46 Drammen 3 46 Eidsvoll 1 (46) Enebakk 3 46 Flesberg 1 (46) Flå 1 (49) Fredrikstad 2 49 Frogn 2 46 Gjerdrum 1 (46) Gol 1 (46) Halden 1 (46) Hemsedal 1 (52) Hol 2 52 Hole 1 (46) Hurdal 1 (46) Hvaler 2 49 Indre Østfold 1 (46) Jevnaker1 2 46 Kongsberg 3 52 Kristiansand 1 (46) Krødsherad 1 (46) Lier 2 46 Lillestrøm 3 46 Lunner 2 46 Lørenskog 3 46 Marker 1 (45) Modum 2 46 Moss 3 49 Nannestad 1 (49) Nes 1 (46) Nesbyen 1 (49) Nesodden 1 (52) Nittedal 2 46 Nordre Follo2 3 46 Nore og Uvdal 1 (49) 2 Oslo 3 46 Rakkestad 1 (46) Ringerike 3 52 Rollag 1 (52) Rælingen 3 46 Råde 1 (46) Sarpsborg 2 49 Sigdal3 2 46 Skiptvet 1 (51) Stavanger 1 (46) Trondheim 2 52 Ullensaker 1 (52) Vestby 1 (46) Våler 1 (46) Øvre Eiker 2 51 Ål 1 (46) Ås 2 46 Note: The random assignment was conducted so that the share of municipalities with ban ( 2 and 3) within each implementation weeks was similar to the share of municipalities without ban (1) within the same (actual) implementation weeks. -

Rutetabeller, Bærum – Oslo Gjelder Fra 1

1 Rutetabeller, Bærum – Oslo Gjelder fra 1. januar 2017 • 130 Sandvika -Skøyen • 140 Bekkestua - Østerås - Skøyen • 140E Hosle - Vika • 150 Gullhaug - Oslo bussterminal • 150E Gullhaug - Vika • 160 Rykkinn - Oslo bussterminal • 160E Rykkinn - Vika 2 Sandvika - Skøyen 130 Gyldig fra: 01.01.2017 Mandag - fredag Monday - Friday Sandvika bussterminalEvje Valler skoleLillehagveienPresteveienFossveienDragveienHøvikveienKrokvoldenStabekk kinoClausenbakkenTrudvangveienJar skole LillengveienLysaker Vækerø Skøyen stasjonSkøyen Første first 0537 0539 0540 0542 0543 0544 0546 0548 0550 0552 0553 0554 0555 0556 0600 0601 0603 0604 0552 0554 0555 0557 0558 0559 0601 0603 0605 0607 0608 0609 0610 0611 0615 0616 0618 0619 Fra from 0607 0609 0610 0612 0613 0614 0616 0618 0620 0622 0623 0624 0625 0626 0630 0631 0633 0634 Hvert every x 15 17 18 20 21 22 24 26 28 30 31 32 33 34 38 39 41 42 7-8 min 22 24 25 27 28 29 31 33 35 37 38 39 40 41 45 46 48 49 x 30 32 33 35 36 37 39 41 43 45 46 47 48 49 53 54 56 57 37 39 40 42 43 44 46 48 50 52 53 54 55 56 00 01 03 04 x 45 47 48 50 51 52 54 56 58 00 01 02 03 04 08 09 11 12 52 54 55 57 58 59 01 03 05 07 08 09 10 11 15 16 18 19 x 00 02 03 05 06 07 09 11 13 15 16 17 18 19 23 24 26 27 07 09 10 12 13 14 16 18 20 22 23 24 25 26 30 31 33 34 Til to 0822 0824 0825 0827 0828 0829 0831 0833 0835 0837 0838 0839 0840 0841 0845 0846 0848 0849 Fra from 0837 0839 0840 0842 0843 0844 0846 0848 0850 0852 0853 0854 0855 0856 0900 0901 0903 0904 Hvert every 52 54 55 57 58 59 01 03 05 07 08 09 10 11 15 16 18 19 15 min 07 09 10 12 13 14 -

Upcoming Projects Infrastructure Construction Division About Bane NOR Bane NOR Is a State-Owned Company Respon- Sible for the National Railway Infrastructure

1 Upcoming projects Infrastructure Construction Division About Bane NOR Bane NOR is a state-owned company respon- sible for the national railway infrastructure. Our mission is to ensure accessible railway infra- structure and efficient and user-friendly ser- vices, including the development of hubs and goods terminals. The company’s main responsible are: • Planning, development, administration, operation and maintenance of the national railway network • Traffic management • Administration and development of railway property Bane NOR has approximately 4,500 employees and the head office is based in Oslo, Norway. All plans and figures in this folder are preliminary and may be subject for change. 3 Never has more money been invested in Norwegian railway infrastructure. The InterCity rollout as described in this folder consists of several projects. These investments create great value for all travelers. In the coming years, departures will be more frequent, with reduced travel time within the InterCity operating area. We are living in an exciting and changing infrastructure environment, with a high activity level. Over the next three years Bane NOR plans to introduce contracts relating to a large number of mega projects to the market. Investment will continue until the InterCity rollout is completed as planned in 2034. Additionally, Bane NOR plans together with The Norwegian Public Roads Administration, to build a safer and faster rail and road system between Arna and Stanghelle on the Bergen Line (western part of Norway). We rely on close