Jordan's National Dish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testimony of Ryan Crocker House Committee on Armed Services

Testimony of Ryan Crocker House Committee on Armed Services Hearing on Afghanistan November 20, 2020 Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Thornberry, it is an honor to appear before you today to discuss the critical issue of the US military mission in Afghanistan and the peace process. Our military has been in Afghanistan almost two decades. After this length oftime, it is important to recall the reasons for our intervention. It was in response to the most devastating attacks on US soil since Pearl Harbor. Those attacks came out of Afghanistan, perpetrated by al-Qaida which was hosted and sheltered there by the Taliban. We gave the Taliban a choice: give up al-Qaida. and we will take no action against you. The Taliban chose a swift military defeat and exile over abandoning their ally. Why is this of any significance today? Because, after nearly two decades, the Taliban leadership sees an opportunity to end that exile and return to power, largely thanks to us. And its links to al-Qaida, the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks, remain very strong. Mr. Chairman, I appear before you today not as a scholar but as a practitioner. At the beginning of January 2002, I had the privilege of reopening our Embassy in Kabul. It was a shattered city in a devastated country. The Kabul airport was closed, its runways crate red and littered with destroyed aircraft. The drive to Kabul from our military base at Bagram was through a wasteland of mud, strewn with mines. Nothing grew. Kabul itself resembled Berlin in 1945 with entire city blocks reduced to rubble. -

By Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

FROM DIWAN TO PALACE: JORDANIAN TRIBAL POLITICS AND ELECTIONS by LAURA C. WEIR Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Pete Moore Department of Political Science CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2013 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Laura Weir candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Pete Moore, Ph.D (chair of the committee) Vincent E. McHale, Ph.D. Kelly McMann, Ph.D. Neda Zawahri, Ph.D. (date) October 19, 2012 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables v List of Maps and Illustrations viii List of Abbreviations x CHAPTERS 1. RESEARCH PUZZLE AND QUESTIONS Introduction 1 Literature Review 6 Tribal Politics and Elections 11 Case Study 21 Potential Challenges of the Study 30 Conclusion 35 2. THE HISTORY OF THE JORDANIAN ―STATE IN SOCIETY‖ Introduction 38 The First Wave: Early Development, pre-1921 40 The Second Wave: The Arab Revolt and the British, 1921-1946 46 The Third Wave: Ideological and Regional Threats, 1946-1967 56 The Fourth Wave: The 1967 War and Black September, 1967-1970 61 Conclusion 66 3. SCARCE RESOURCES: THE STATE, TRIBAL POLITICS, AND OPPOSITION GROUPS Introduction 68 How Tribal Politics Work 71 State Institutions 81 iii Good Governance Challenges 92 Guests in Our Country: The Palestinian Jordanians 101 4. THREATS AND OPPORTUNITIES: FAILURE OF POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE RISE OF TRIBAL POLITICS Introduction 118 Political Threats and Opportunities, 1921-1970 125 The Political Significance of Black September 139 Tribes and Parties, 1989-2007 141 The Muslim Brotherhood 146 Conclusion 152 5. -

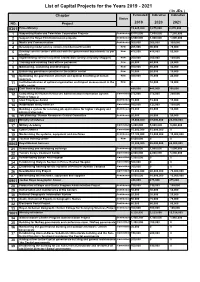

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

Voting for the Devil You Know: Understanding Electoral Behavior in Authoritarian Regimes

VOTING FOR THE DEVIL YOU KNOW: UNDERSTANDING ELECTORAL BEHAVIOR IN AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Natalie Wenzell Letsa August 2017 © Natalie Wenzell Letsa 2017 VOTING FOR THE DEVIL YOU KNOW: UNDERSTANDING ELECTORAL BEHVAIOR IN AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES Natalie Wenzell Letsa, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 In countries where elections are not free or fair, and one political party consistently dominates elections, why do citizens bother to vote? If voting cannot substantively affect the balance of power, why do millions of citizens continue to vote in these elections? Until now, most answers to this question have used macro-level spending and demographic data to argue that people vote because they expect a material reward, such as patronage or a direct transfer via vote-buying. This dissertation argues, however, that autocratic regimes have social and political cleavages that give rise to variation in partisanship, which in turn create different non-economic motivations for voting behavior. Citizens with higher levels of socioeconomic status have the resources to engage more actively in politics, and are thus more likely to associate with political parties, while citizens with lower levels of socioeconomic status are more likely to be nonpartisans. Partisans, however, are further split by their political proclivities; those that support the regime are more likely to be ruling party partisans, while partisans who mistrust the regime are more likely to support opposition parties. In turn, these three groups of citizens have different expressive and social reasons for voting. -

Jordan Parliamentary Elections, 20 September

European Union Election Observation Mission The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Parliamentary Election 20 September 2016 Final Report European Union Election Observation Mission The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Parliamentary Election 20 September 2016 Final Report European Union Election Observation Mission The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Parliamentary Election, 20 September 2016 Final Report, 13 November 2016 THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN Parliamentary Election, 20 September 2016 EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Page 1 Key Abbreviations Page 3 1. Executive Summary Page 4 2. Introduction and Acknowledgements Page 7 3. Political Context Page 8 4. Legal Framework Page 10 4.1 Applicability of International Human Rights Law 4.2 Constitution 4.3 Electoral Legislation 4.4 Right to Vote 4.5 Right to Stand 4.6 Right to Appeal 4.7 Electoral Districts 4.8 Electoral System 5. Election Administration Page 22 5.1 Election Administration Bodies 5.2 Voter Registration 5.3 Candidate Registration 5.4 Voter Education and Information 5.5 Institutional Communication 6 Campaign Page 28 6.1 Campaign 6.2 Campaign Funding 7. Media Page 30 7.1 Media Landscape 7.2 Freedom of the Media 7.3 Legal Framework 7.4 Media Violations 7.5 Coverage of the Election 8. Electoral Offences, Disputes and Appeals Page 35 9. Participation of Women, Minorities and Persons with Disabilities Page 38 __________________________________________________________________________________________ While this Final Report is translated in Arabic, the English version remains the only original Page 1 of 131 European Union Election Observation Mission The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Parliamentary Election, 20 September 2016 Final Report, 13 November 2016 9.1 Participation of Women 9.2 Participation of Minorities 9.3 Participation of Persons with Disabilities 10. -

Entrepreneurship in Jordan: the Eco-System of the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (Sesos)

Entrepreneurship in Jordan: the Eco-system of the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (SESOs) Amani Jarrar ( [email protected] ) Philadelphia University, Department of Development Studies Research Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Social Entrepreneurship, Eco-system, Jordan Posted Date: March 22nd, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-334076/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/50 Abstract This study aims at assessing the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (SESOs) in Jordan with an updated eco-system reecting the better resourced Social Entrepreneurship eco-system characterized with comprehensive information; covering the stakeholders’ identication data, ongoing projects and initiatives, work scope, and their targeted groups, accurate data based on a well-developed survey and analysis of the survey data by our experts. This study also aims at assessing the SESOs capacity by coincide their desired needs and their actual needs, and limit the social innovation concept variation among the different institutions in the ecosystem. This study provides a survey analysis for the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (SESOs), and an attempt to identify their characteristics and roles in Jordan by adopting the qualitative and quantitative analysis approach as its methodology. Results show that (57.89%) of the SESO’s in Jordan have dedicated programs that focus on women's inclusion, and that (68.42%) are hiring more than 50% in their staff. Besides that, results also show that (59.65%) of the SESO’s in Jordan did not dedicate programs for people with disability (PWD); which is a high portion in neglecting this segment of people. -

Amman, Jordan

MINISTRY OF WATER AND IRRIGATION WATER YEAR BOOK “Our Water situation forms a strategic challenge that cannot be ignored.” His Majesty Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein “I assure you that the young people of my generation do not lack the will to take action. On the contrary, they are the most aware of the challenges facing their homelands.” His Royal Highness Hussein bin Abdullah Imprint Water Yearbook Hydrological year 2016-2017 Amman, June 2018 Publisher Ministry of Water and Irrigation Water Authority of Jordan P.O. Box 2412-5012 Laboratories & Quality Affairs Amman 1118 Jordan P.O. Box 2412 T: +962 6 5652265 / +962 6 5652267 Amman 11183 Jordan F: +962 6 5652287 T: +962 6 5864361/2 I: www.mwi.gov.jo F: +962 6 5825275 I: www.waj.gov.jo Photos © Water Authority of Jordan – Labs & Quality Affairs © Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources Authors Thair Almomani, Safa’a Al Shraydeh, Hilda Shakhatreh, Razan Alroud, Ali Brezat, Adel Obayat, Ala’a Atyeh, Mohammad Almasri, Amani Alta’ani, Hiyam Sa’aydeh, Rania Shaaban, Refaat Bani Khalaf, Lama Saleh, Feda Massadeh, Samah Al-Salhi, Rebecca Bahls, Mohammed Alhyari, Mathias Toll, Klaus Holzner The Water Yearbook is available online through the web portal of the Ministry of Water and Irrigation. http://www.mwi.gov.jo Imprint This publication was developed within the German – Jordanian technical cooperation project “Groundwater Resources Management” funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) Implemented by: Foreword It is highly evident and well known that water resources in Jordan are very scarce. -

Jordan Parliamentary Elections January 23, 2013

JORDAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS JANUARY 23, 2013 International Republican Institute JORDAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS JANUARY 23, 2013 INTERNATIONAL REPUBLICAN INSTITUTE WWW.IRI.ORG | @IRIGLOBAL © 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY AND ABBREVIATIONS 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 INTRODUCTION 10 POLITICAL CONTEXT 12 Economic Challenges 15 Demographic Breakdown 15 Gender Roles in Government and Society 17 Media 17 Security 18 ELECTORAL FRAMEWORK 19 Technical Improvements 19 Shortcomings 19 Electoral Administration Bodies 20 PRE-ELECTION ENVIRONMENT 22 Voter Registration 22 Voter Education 24 Candidate Registration 25 Candidates 26 National List 26 Political Parties 27 Boycott 27 Campaigning 28 Violations of Campaign Regulations 30 ELECTION DAY 32 Turnout 32 Voting Process 33 Closing and Counting Process 34 Security 35 POST-ELECTION DAY AND FINAL RESULTS 36 Election Results 37 RECOMMENDATIONS 39 Electoral Framework 39 Electoral Administration Bodies 40 Formation of Government 40 Electoral Complaint Resolution 40 3 IRI IN JORDAN 42 APPENDICES Regional Map IRI Pre-election Assessment Statement, December 3, 2012 IRI Election Observation Mission Announcement Press Release, January 17, 2013 IRI Preliminary Statement on Jordan’s Parliamentary Elections, January 24, 2013 4 2013 Jordan Parliamentary Elections GLOSSARY AND ABBREVIATIONS Civil Status and Passport The CSPD is the government entity that handles Department (CSPD) issues of citizenship. It performs numerous tasks including issuing travel documents and national identification cards, registering new citizens, documenting deaths and certifying divorces. During the run-up to the elections, the CSPD was the government institution responsible for voter registration and the issuance of election cards. District Election Commission (DEC) The chief electoral body responsible for administering elections at the district level; each of the 45 districts nation-wide had a DEC. -

Cultural Detente: John Le Carré from the Cold to the Thaw Leah Nicole Huesing University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Theses Graduate Works 4-14-2016 Cultural Detente: John le Carré from the Cold to the Thaw Leah Nicole Huesing University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Huesing, Leah Nicole, "Cultural Detente: John le Carré from the Cold to the Thaw" (2016). Theses. 168. http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis/168 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Huesing 1 Cultural Détente: John le Carré from the Cold to the Thaw Leah Huesing B.A. History, Columbia College, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Missouri-St. Louis in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History May, 2016 Advisory Committee Peter Acsay, Ph. D Chairperson Minsoo Kang, Ph.D. Carlos Schwantes, Ph.D. Huesing 2 Abstract British spy fiction author John le Carré inspired Cultural Détente, a movement in American popular culture which banished the simplicities of the 1950’s and replaced it with a relaxation of tensions from 1960-1965. Cultural Détente manifested from within Western liberal, democratic society after the strict conformities of the 1950s. After the dissipation of McCarthyism and the anti-Communist crusaders, the public was ready to embrace a ‘thaw’ in tensions. Even with all of the evidence already in place, there has yet to be any historical evaluation of a 1960s Cultural Détente that anticipated and made possible the détente of Richard Nixon. -

International Security Environment to the Year 2020: Global Trends Analysis

DTIC ELEeTE DEC 1 1 1995 LIBRARY F OF CONGRESS INTERNATIONAL SECURITY ENVIRONMENT TO THE YEAR 2020: GLOBAL TRENDS ANALYSIS *DTlC USERS ONL "" ~995~20S 067 September 30, 1990 Coordinator Contributors Carol Migdalovitz Ronald Dolan Ihor Gawdiak Stuart Hibben Eric Hooglund Tim Merrill David Osborne Eric Solsten Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, DC 20540-5220 Tel: (202) 707-9905 Fax: (202) 707-9920 --~------~--------------------------------------, CONTENTS Page Executive Summary ii I. Prospects for post-Deng China ............................- 1 II. Japanese-Soviet relations: from political stalemate to economic interdependence ..................................... 9 III. The new Europe: economic integration amidst political division . .. 19 IV. Resurgent nationalism and ethnic forces in the Soviet Union ........ 27 V. Transformed nations and ethnic unrest in Eastern Europe .......... 41 VI. The Middle East: religio-nationalism and the quest for peace ........ 48 VII. Mexico as a microcosm for Latin America and the Third World ....... 59 VIII. Energy technology in the next thirty years .................... -- 69 - I !\cG;ionFOr ------ --- --'" ._- -"-... -----"-.-~--. - \r-:·;·,~; ('I) I, P , r,I".) ,,,., ,,'., (".' rf i :;' i: i '- iii ~--.--.-. -.-. .*DTIC USERS ONL yr, Dic~t II\J;sir'·:~·;-~/~~~··-·-----· l~ j ---.-........~,"-,-, ~'.~" ~., .... <c~,_.:,~ .... ___'" INTERNATIONAL SECURITY ENVIRONMENT TO THE YEAR 2020: GLOBAL TRENDS ANALYSIS Executive Summary This series of analytical summaries attempts to identify and analyze trends which will influence international security policy through the next three decades. An assessment of the changed world that these trends will produce is vital for Army planners. In this survey, we discuss underlying trends driving change and predict realities ten and thirty years hence. Forecasting events on a global scale is, at best, a hazardous exercise. -

Tafila Region Wind Power Projects Cumulative Effects Assessment © International Finance Corporation 2017

Tafila Region Wind Power Projects Cumulative Effects Assessment © International Finance Corporation 2017. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 Internet: www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. IFC encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly, and when the reproduction is for educational and non-commercial purposes, without a fee, subject to such attributions and notices as we may reasonably require. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The contents of this work are intended for general informational purposes only and are not intended to constitute legal, securities, or investment advice, an opinion regarding the appropriateness of any investment, or a solicitation of any type. IFC or its affiliates may have an investment in, provide other advice or services to, or otherwise have a financial interest in, certain of the companies and parties (including named herein. -

Jordan's 2013 Elections: a Further Boost for Tribes

Report March 2013 Jordan’s 2013 elections: a further boost for tribes By Mona Christophersen1 Executive summary The 2013 parliamentary elections in Jordan came after two years of protests demanding democratic reform. This report is based on qualitative interviews with protesters and politicians in Jordan since 2011. Protesters wanted change to the undemocratic “one-person-one-vote” election law, which favours tribal candidates over urban areas where the Muslim Brotherhood has strong support. The elections were dominated by independent and tribal candidates who used general slogans and often lacked either an ideology or a political strategy. Constituencies were usually candidates’ relatives and friends. In a context of weak political parties, the tribes resurfaced as the main link between the people and the authorities. Jordan has about three million eligible voters. Roughly two million registered for the elections, but only one million voted. With support from one-third of the voters, the new parliament continues to have a weak legitimacy, despite transparent and fair elections. As a result the street protests are expected to continue. But Jordanians have learned from the Arab Spring: they fear the instability experienced in neighbouring countries. Stability is now more precious than change and secular protesters are dreading the Muslim Brotherhood coming to power. Having learned that the Brotherhood does not bring their kind of democratic development, people in Jordan will demand reform instead of revolution. Introduction management and sale of state property, and also the From the outset the 2013 elections in Jordan were tradition of vote buying that resembles patron-client considered to be free and fair, but they did not address relations, which together are alienating people from the fundamental issues facing Jordanian society.