Napoleon's Hundred Days and the Shaping of a Dutch Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scholars, Travellers and Trade

SCHOLARS, TRAVELLERS AND TRADE Today, the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden is internationally known for its outstanding archaeological collections. Yet its origins lie in an insignificant assortment of artefacts used for study by Leiden University. How did this transformation come about? Ruurd Halbertsma has delved into the archives to show that the appoint- ment of Caspar Reuvens as Professor of Archaeology in 1818 was the crucial turning point. He tells the dramatic story of Reuvens’ struggle to establish the museum, with battles against rival scholars, red tape and the Dutch attitude of neglect towards archaeological monuments. It was Reuvens who trained archaeological agents to investigate and excavate ancient sites, and bring back the antiquities on which the museum’s importance rests. Though he was operating long before the current debate on whether collecting anti- quities is legal trade or cultural looting, Reuvens recognized the potential ethical problems inherent in achieving a world-class collection. In this, he was ahead of his time. Scholars, Travellers and Trade throws new light on the process of creating a national museum and the difficulties of convincing society of the value of the past – issues with which museums are still wrestling. It also highlights the difficulties that an archaeological pioneer had in establishing his discip- line as a fully accepted branch of academia. Ruurd B. Halbertsma is Curator of the Classical Department at the National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden, The Netherlands. i ii SCHOLARS, TRAVELLERS AND TRADE The pioneer years of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, 1818–40 R.B. Halbertsma I~ ~~o~;~;n~~~up LONDON AND NEW YORK iii First published 2003 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2003 R.B. -

PDF Van Tekst

Geschiedenis van de techniek in Nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving 1800-1890. Deel VI Techniek en samenleving hoofdredactie H.W. Lintsen bron H.W. Lintsen (red.), Geschiedenis van de techniek in Nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving 1800-1890. Deel VI. Techniek en samenleving. Walburg Pers, Zutphen 1995 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/lint011gesc06_01/colofon.htm © 2009 dbnl / H.W. Lintsen / de afzonderlijke auteurs en/of hun rechthebbenden 10 Herinneringsdoek aan de eerste tentoonstelling van de ‘Wonderen der Industrie van alle Landen’ te Londen in 1851. Tot de talloze souvenirs, zoals albums, prenten, catalogi, beschrijvingen en plattegronden van tentoonstelling en omgeving, hoorde ook deze bedrukte textieldoek. De voorstelling van het hoofdgebouw in het midden is omlijst door de vlaggen der deelnemende naties en de portretten van prins Albert, de bedenker van deze tentoonstelling, en koningin Victoria, die de opening verrichtte. Geschiedenis van de techniek in Nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving 1800-1890. Deel VI 11 Techniek en samenleving Geschiedenis van de techniek in Nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving 1800-1890. Deel VI 12 Het Paleis voor Volksvlijt te Amsterdam in aanbouw, april 1862, (onder) en het oorspronkelijk outwerp voor een gebouw voor de eerste wereldtentoonstelling in Londen (boven). Al snel bleek dat een revolutionair gebouw als Crystal Palace vrij algemeen als te modern en te functioneel werd beschouwd, zodat volgende tentoonstellingsgebouwen weer meer leken op de ‘klassieke’ vormen die ook het oorspronkelijke gebouw voor Londen-1851 hadden gedomineerd: koepels, venvijzingen naar allerlei vroegere bouwstijlen etc. Het Paleis voor Volksvlijt, dat door Cornelis Outshoorn was ontworpen, kende ook die schijnbare tegenstelling van ‘oude’ vormen en nieuwe materialen en bouworganisatie. -

State Building Participants Coordinator

Theme 6: State Building Participants Coordinator: Ido de Haan (Utrecht University) Participants In alphabetical order 1. Alberto Feenstra 2. Klaas van Gelder 3. Jens van de Maele 4. Karen van Nieuwenhuyze 5. Marijcke Schillings 6. Pieter Slaman 7. Tamàs Székely 1. Alberto Feenstra University of Amsterdam Paper for the Conference: Keeping the Ship of State Afloat. Zeeland's Sovereign Debt Management, 1600-1800 (Working) Title of dissertation Finance without frontiers? The integration of provincial money markets in the Dutch Republic. Supervisor(s) J.P.B. Jonker Short Biography Alberto Feenstra (1982) studied Global History at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Previously he has been employed as research assistant at the Geldmuseum (Money Museum) in Utrecht. Currently he is employed as a PhD Candidate at the University of Amsterdam, where he works on the integration of financial markets within the Dutch Republic. This research examines the domestic capital market developments within the Dutch Republic. Whereas international relations have been studied more extensively the domestic ‘rooting’ of each location has remained under-researched. Yet, as the current crisis clearly showed, international capital markets are intertwined with domestic ones and they mutually influence each other. Hence, this research aims to improve our understanding of capital markets by taking into account their specific local context, such as political, legal and social institutions. Contact information [email protected] Website/Social Media - 1 2. Klaas van Gelder -

Kansen in Het Koninkrijk. Studiebeurzen 1815-2015

KANSEN IN HET KONINKRIJK STUDIEBEURZEN 1815.2015 Pieter Slaman, Wouter Marchand en Ruben Schalk Boom – Amsterdam Deze publicatie is tot stand gekomen met steun van het Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap, het Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties, de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, de Universiteit Leiden, slotbeschouwing de Universiteit Utrecht en de Dienst Uitvoering Onderwijs Auteurs Pieter Slaman, Wouter Marchand en Ruben Schalk Begeleidingscommissie 1815 -2015 Jan Derksen, Leen Dorsman, Maarten Duijvendak, Oscar Gelderblom, Adriaan in ’t Groen, Willem Otterspeer en Richard Paping 9 10 11 12 Eindredactie Jan Derksen buitenland leerlingstelsel studiefinanciering sociale Vormgeving Gert Jan Slagter voor iedereen gevolgen na 1945 na Beeldredactie en beeldresearch Corrie van Maris Ontwerp en uitvoering Risograph Print Gerard Schoneveld Beeldbewerking Risograph Print Tomas Janicek Druk Wilco, Amersfoort 6 7 8 © 2015 Pieter Slaman, Wouter Marchand en Ruben Schalk koninkrijk sociaal bezetting overzee stelsel Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde 1945 tot uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, 1 2 3 4 5 zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. universiteiten arbeidsmarkt onderwijzers- schoolstrijd ambachten opleiding No part of this book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever eeuw 19e without the written permission of the publisher. isbn 9789089535405 inleiding nur 680 www.uitgeverijboom.nl 9 Inleiding Studiefinanciering in de negentiende eeuw 14 1. Universiteiten 26 2. Arbeidsmarkt 38 3. Onderwijzersopleiding 50 4. Schoolstrijd beelden i 68 5. Ambachten Studiefinanciering tot 1945 88 6. -

A Tiny Spot on the Earth

A Tiny Spot on the Earth A Tiny Spot on the Earth The Political Culture of the Netherlands in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Piet de Rooy Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Nationaal Archief/Spaarnestad. Photo/Wilh. L. Stuifbergen Translated by Vivien Collingwood Cover design: Suzan Beijer Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 704 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 415 0 (pdf) e-isbn 978 90 4852 416 7 (ePub) nur 686 © Piet de Rooy/ Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Table of Contents Introduction 7 1. Long Live the Republic! 17 1798: The Constitution 2. A New Society is Being Created Here 43 1813: The Nation State 3. Everything is a Motley 73 1848: Parliamentary Democracy 4. Following the American Example 111 1879: The Political Party 5. Justice and Love 147 Fin de siècle: Ideology 6. The Nation is Divided into Parties 185 1930: The Pillarized-Corporate Order 7. Fundamental Changes in Mentality 229 1966: The Cultural Revolution 8. That’s Not Politics! 265 2002: Populism 9. A Tiny Spot 289 Political culture Acknowledgements 299 Notes 301 Bibliography 371 Index of persons 403 All government, indeed every human benefit and enjoyment, every virtue, and every prudent act, is founded on compromise and barter. -

Arnout Van Der Meer

©2014 Arnout Henricus Cornelis van der Meer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED AMBIVALENT HEGEMONY: CULTURE AND POWER IN COLONIAL JAVA, 1808-1927 by ARNOUT HENRICUS CORNELIS VAN DER MEER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Michael Adas And approved by: _________________________________" _________________________________" _________________________________" _________________________________New Brunswick, New Jersey " OCTOBER, 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Ambivalent Hegemony: Culture and Power in Colonial Java, 1808-1927 By ARNOUT HENRICUS CORNELIS VAN DER MEER Dissertation Director: Professor Michael Adas “Ambivalent Hegemony” explores the Dutch adoption and subsequent rejection of Javanese culture, in particular material culture like dress, architecture, and symbols of power, to legitimize colonial authority around the turn of the twentieth century. The Dutch established an enduring system of hegemony by encouraging cultural, social and racial mixing; in other words, by embedding themselves in Javanese culture and society. From the 1890s until the late 1920s this complex system of dominance was transformed by rapid technological innovation, evolutionary thinking, the emergence of Indonesian nationalism, and the intensification of the Dutch “civilizing” mission. This study traces the interactions between Dutch and Indonesian civil servants, officials, nationalists, journalists and novelists, to reveal how these transformations resulted in the transition from cultural hegemony based on feudal traditions and symbols to hegemony grounded in enhanced Westernization and heightened coercion. Consequently, it is argued that we need to understand the civilizing mission ideology and the process of modernization in the colonial context as part of larger cultural projects of control. -

Downloaded From: Books at JSTOR, EBSCO, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, OAPEN, Project MUSE, and Many Other Open Repositories

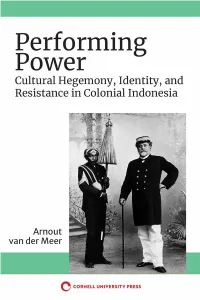

Performing Power Cultural Hegemony, Identity, and Resistance in Colonial Indonesia • Arnout van der Meer Mahinder Kingra Chiara Formichi (ex officio) Tamara Loos Thak Chaloemtiarana Andrew Willford Copyright © by Cornell University e text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives . International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/./. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, East State Street, Ithaca, New York . Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Meer, Arnout van der, – author. Title: Performing power: cultural hegemony, identity, and resistance in colonial Indonesia / Arnout van der Meer. Description: Ithaca, [New York]: Southeast Asia Program Publications, an imprint of Cornell University Press, . | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identiers: LCCN (print) | LCCN (ebook) | ISBN (hardcover) | ISBN (paperback) | ISBN (epub) | ISBN (pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Politics and culture—Indonesia—Java—History— th century. | Politics and culture—Indonesia—Java—History—th century. | Group identity—Indonesia—Java—History— th century. | Group identity—Indonesia—Java—History—th century. | Indonesia—Politics and government— – . | Java (Indonesia)—Social life and customs— th century. | Java (Indonesia)—Social life and customs—th century. Classication: LCC DS.M (print) | LCC DS (ebook) | DDC ./—dc LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ Cover image: Resident P. Sijtho of Semarang with his servant holding his gilded payung, . Source: Leiden University Library, Royal Netherlands Institute for Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies . -

Hybrid Ambitions

Hybrid Ambitions Cover illustration: A field sketch of Reinwardt and his helpers made by Jannes Theodorus Bik during an expedition through West-Java in 1819. © Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Album van schetsen en kleurteekeningen door J.Th. Bik nagelaten aan J.F. Bik. Signature: RP-T-1999-141. Cover design: Maedium Utrecht Lay-out: Andreas Weber ISBN 978 90 8728 166 3 NUR 680 © A. Weber / Leiden University Press 2012 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Hybrid Ambitions Science, Governance, and Empire in the Career of Caspar G.C. Reinwardt (1773-1854) PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof. mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 8 mei 2012 klokke 15.00 uur door ANDREAS WEBER geboren te Ellwangen/Jagst (Duitsland) in 1979 Promotiecommissie Promotor: prof. dr. J.L. Blussé van Oud Alblas Copromotor: prof. dr. L.L. Roberts Overige leden: prof. dr. H.W. van den Doel prof. dr. H. Beukers prof. dr. K.J.P.F.M. Jeurgens prof. dr. F.H. van Lunteren prof. dr. M. Häberlein (University of Bamberg) dr. C. Smeenk (NCB Naturalis) Meinen Eltern gewidmet Contents Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 PART I: -

Hybrid Ambitions

Andreas Weber · Weber Andreas Andreas Weber Hybrid Ambitions Hybrid Hybrid Ambitions Science, Governance, and Empire in the Career of Caspar G.C. Reinwardt (1773-1854) The life of the German chemist-apothecary Caspar Georg Carl Reinwardt (1773-1854) offers a fascinating window on Dutch culture and society in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By providing an in-depth analysis of his multi-faceted career in the Netherlands and the Malay Archi- pelago, this study sheds light on the co-evolutionary character of science, governance, and empire. It argues that the seeds of Reinwardt’s professional flexibility lay in his practical training in one of Amsterdam’s chemical workshops and his socializa- tion in a broader cultural context where the improvement of society and economy played a crucial role. Andreas Weber is a historian with a special interest in the history of Dutch colonialism and the history of science. lup dissertations LUP leiden university press Weber.indd 1-3 25-3-2012 9:41:41 Hybrid Ambitions Cover illustration: A field sketch of Reinwardt and his helpers made by Jannes Theodorus Bik during an expedition through West-Java in 1819. © Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Album van schetsen en kleurteekeningen door J.Th. Bik nagelaten aan J.F. Bik. Signature: RP-T-1999-141. Cover design: Maedium Utrecht Lay-out: Andreas Weber ISBN 978 90 8728 166 3 NUR 680 © A. Weber / Leiden University Press 2012 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

The First Contest for Singapore

THE FIRST CONTEST FOR SINGAPORE 1819.1824 VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL~ LAND· EN VOLKENKUNDE DEEL XXVII THE FIRST CONTEST FOR SINGAPORE 1819-1824 BY HARRY J. MARKS Department 0/ Bi8tory, Uni.,..,ity 0/ Connecticut Storr., Conneceicut, U.S.A. 'S·GRAVENHAGE - MARTINUS NIJHOFF - 1959 PREFACE For directing my attention to the problem of the British acquisition of Singapore as a problem worth investigating, as weIl as for subsequent encouragement, I am deeply indebted to Professor Dietrich Gerhard, now of Washington University, St. Louis. For various acts of kindness I owe thanks to my colleague, Professor Fred A. Cazel, Jr.; to Dr. J. Norman Parmer, now of the University of Maryland; and most recently to Professor C. Northcote Parkinson, of the University of Malaya. Since none of these scholars has seen the manuscript of this study, I can thank them warmly while relieving them of responsibility for its defects. To librarians and libraries I am indebted: to Miss Roberta K. Smith, Reference Librarian of the Wilbur L. Cross Library of the University of Connecticut, for procuring many volumes for me through inter library loan; to the libraries of Harvard, Vale, and Columbia univer sities and Trinity College (Hartford), for use of their facilities; to the Commonwealth Relations Office, London, for permission to have two volumes of Dutch Records microfilmed. I must thank Mrs. Betty G. Seaver for her personal interest in the manuscript, much of which, to its benefit, she typed. FinaIly, I must express appreciation to the administrative authorities of the University of Connecticut for a semester's sabbaticalleave which permitted a great deal of the research and writing to be completed. -

Brugmans.Pdf

TEUNIS WILLEM VAN HEININGEN THE CORRESPONDENCE OF SEBALD JUSTINUS BRUGMANS (1763-1819) The Hague 2010 Dutch - History of Science - Web Centre (www.dwc.knaw.nl) Portrait cover and on p. 6: © Academisch Historisch Museum, Leiden Digital series: Tools and Sources for the History of Science in the Netherlands, volume 1 (2008). (Huib J. Zuidervaart & Ilja Nieuwland, editors) Digital publication of the Dutch - History of Science - Web Centre (www.dwc.knaw.nl) of the Huygens Instituut (Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences - KNAW) The Hague, The Netherlands Available in ‘Printing on Demand’ since 2010 at Uitgeverij U2pi BV - JouwBoek.nl Voorburg (www.jouwboek.nl), The Netherlands ISBN 978-90-8759-158-8 © The Author / DWC- Huygens Institute (KNAW) – Digital edition 2008 / PoD 2010 CONTENTS Introduction Codes of the locations of provenance of the documents Abbreviations of the disciplines and subjects 1 Biography 2 Correspondence with Jan Hendrik van Swinden 3 Correspondence with Sir Joseph Banks 4 Leyden University, Rectorships and career 5 Pharmacopoea Batava and Pharmacopoea Belgica 6 Military Medicine 7 Correspondence with Christianus Carolus Henricus van der Aa 8 Correspondence with Martinus van Marum 9 Correspondence with Johan Meerman 10 Correspondence with Gerardus Vrolik 11 Correspondence with Jacob van Breda and Jacobus Gijsbertus Samuel van Breda 12 The Cabinet of Natural History of the Stadholder 13 Building up a collection 14 Miscellaneous Biographical notes Correspondence S.J. Brugmans / 1 INTRODUCTION This publication is the result of an investigation of documents kept in several archives and libraries in the Netherlands and abroad. The research has been carried out between 1995 and 2004. -

Tilburg University Regeneration And

Tilburg University Regeneration and hegemony: Franco-Batavian relations in the Revolutionary Era: A legal approach (1795-1803) Kubben, R.M.H. Publication date: 2009 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Kubben, R. M. H. (2009). Regeneration and hegemony: Franco-Batavian relations in the Revolutionary Era: A legal approach (1795-1803). Wolf Legal Publishers (WLP). General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. sep. 2021 REGENERATION AND HEGEMONY Franco-Batavian Relations in the Revolutionary Era; a legal approach 1795-1803 PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Tilburg, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op vrijdag 19 juni 2009 om 14.15 uur door Raymond Maria Hubertus Kubben geboren op 18 mei 1980 te Geleen promotiecommissie promotores: Prof.