I960 CA/CF Microprocessor User's Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ece585 Lec2.Pdf

ECE 485/585 Microprocessor System Design Lecture 2: Memory Addressing 8086 Basics and Bus Timing Asynchronous I/O Signaling Zeshan Chishti Electrical and Computer Engineering Dept Maseeh College of Engineering and Computer Science Source: Lecture based on materials provided by Mark F. Basic I/O – Part I ECE 485/585 Outline for next few lectures Simple model of computation Memory Addressing (Alignment, Byte Order) 8088/8086 Bus Asynchronous I/O Signaling Review of Basic I/O How is I/O performed Dedicated/Isolated /Direct I/O Ports Memory Mapped I/O How do we tell when I/O device is ready or command complete? Polling Interrupts How do we transfer data? Programmed I/O DMA ECE 485/585 Simplified Model of a Computer Control Control Data, Address, Memory Data Path Microprocessor Keyboard Mouse [Fetch] Video display [Decode] Printer [Execute] I/O Device Hard disk drive Audio card Ethernet WiFi CD R/W DVD ECE 485/585 Memory Addressing Size of operands Bytes, words, long/double words, quadwords 16-bit half word (Intel: word) 32-bit word (Intel: doubleword, dword) 0x107 64-bit double word (Intel: quadword, qword) 0x106 Note: names are non-standard 0x105 SUN Sparc word is 32-bits, double is 64-bits 0x104 0x103 Alignment 0x102 Can multi-byte operands begin at any byte address? 0x101 Yes: non-aligned 0x100 No: aligned. Low order address bit(s) will be zero ECE 485/585 Memory Operand Alignment …Intel IA speak (i.e. word = 16-bits = 2 bytes) 0x107 0x106 0x105 0x104 0x103 0x102 0x101 0x100 Aligned Unaligned Aligned Unaligned Aligned Unaligned word word Double Double Quad Quad address address word word word word -----0 address address address address -----00 ----000 ECE 485/585 Memory Operand Alignment Why do we care? Unaligned memory references Can cause multiple memory bus cycles for a single operand May also span cache lines Requiring multiple evictions, multiple cache line fills Complicates memory system and cache controller design Some architectures restrict addresses to be aligned Even in architectures without alignment restrictions (e.g. -

Avaya Aura® Communication Manager Hardware Description and Reference

Avaya Aura® Communication Manager Hardware Description and Reference Release 7.0.1 555-245-207 Issue 2 May 2016 © 2015-2016, Avaya, Inc. Link disclaimer All Rights Reserved. Avaya is not responsible for the contents or reliability of any linked Notice websites referenced within this site or Documentation provided by Avaya. Avaya is not responsible for the accuracy of any information, While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the statement or content provided on these sites and does not information in this document is complete and accurate at the time of necessarily endorse the products, services, or information described printing, Avaya assumes no liability for any errors. Avaya reserves or offered within them. Avaya does not guarantee that these links will the right to make changes and corrections to the information in this work all the time and has no control over the availability of the linked document without the obligation to notify any person or organization pages. of such changes. Licenses Warranty THE SOFTWARE LICENSE TERMS AVAILABLE ON THE AVAYA Avaya provides a limited warranty on Avaya hardware and software. WEBSITE, HTTPS://SUPPORT.AVAYA.COM/LICENSEINFO, Refer to your sales agreement to establish the terms of the limited UNDER THE LINK “AVAYA SOFTWARE LICENSE TERMS (Avaya warranty. In addition, Avaya’s standard warranty language, as well as Products)” OR SUCH SUCCESSOR SITE AS DESIGNATED BY information regarding support for this product while under warranty is AVAYA, ARE APPLICABLE TO ANYONE WHO DOWNLOADS, available to Avaya customers and other parties through the Avaya USES AND/OR INSTALLS AVAYA SOFTWARE, PURCHASED Support website: https://support.avaya.com/helpcenter/ FROM AVAYA INC., ANY AVAYA AFFILIATE, OR AN AVAYA getGenericDetails?detailId=C20091120112456651010 under the link CHANNEL PARTNER (AS APPLICABLE) UNDER A COMMERCIAL “Warranty & Product Lifecycle” or such successor site as designated AGREEMENT WITH AVAYA OR AN AVAYA CHANNEL PARTNER. -

Reverse Engineering X86 Processor Microcode

Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz, Ruhr-University Bochum https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity17/technical-sessions/presentation/koppe This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium August 16–18, 2017 • Vancouver, BC, Canada ISBN 978-1-931971-40-9 Open access to the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz Ruhr-Universitat¨ Bochum Abstract hardware modifications [48]. Dedicated hardware units to counter bugs are imperfect [36, 49] and involve non- Microcode is an abstraction layer on top of the phys- negligible hardware costs [8]. The infamous Pentium fdiv ical components of a CPU and present in most general- bug [62] illustrated a clear economic need for field up- purpose CPUs today. In addition to facilitate complex and dates after deployment in order to turn off defective parts vast instruction sets, it also provides an update mechanism and patch erroneous behavior. Note that the implementa- that allows CPUs to be patched in-place without requiring tion of a modern processor involves millions of lines of any special hardware. While it is well-known that CPUs HDL code [55] and verification of functional correctness are regularly updated with this mechanism, very little is for such processors is still an unsolved problem [4, 29]. known about its inner workings given that microcode and the update mechanism are proprietary and have not been Since the 1970s, x86 processor manufacturers have throughly analyzed yet. -

Computer Architectures an Overview

Computer Architectures An Overview PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 25 Feb 2012 22:35:32 UTC Contents Articles Microarchitecture 1 x86 7 PowerPC 23 IBM POWER 33 MIPS architecture 39 SPARC 57 ARM architecture 65 DEC Alpha 80 AlphaStation 92 AlphaServer 95 Very long instruction word 103 Instruction-level parallelism 107 Explicitly parallel instruction computing 108 References Article Sources and Contributors 111 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 113 Article Licenses License 114 Microarchitecture 1 Microarchitecture In computer engineering, microarchitecture (sometimes abbreviated to µarch or uarch), also called computer organization, is the way a given instruction set architecture (ISA) is implemented on a processor. A given ISA may be implemented with different microarchitectures.[1] Implementations might vary due to different goals of a given design or due to shifts in technology.[2] Computer architecture is the combination of microarchitecture and instruction set design. Relation to instruction set architecture The ISA is roughly the same as the programming model of a processor as seen by an assembly language programmer or compiler writer. The ISA includes the execution model, processor registers, address and data formats among other things. The Intel Core microarchitecture microarchitecture includes the constituent parts of the processor and how these interconnect and interoperate to implement the ISA. The microarchitecture of a machine is usually represented as (more or less detailed) diagrams that describe the interconnections of the various microarchitectural elements of the machine, which may be everything from single gates and registers, to complete arithmetic logic units (ALU)s and even larger elements. -

Modern Processor Design: Fundamentals of Superscalar

Fundamentals of Superscalar Processors John Paul Shen Intel Corporation Mikko H. Lipasti University of Wisconsin WAVELAND PRESS, INC. Long Grove, Illinois To Our parents: Paul and Sue Shen Tarja and Simo Lipasti Our spouses: Amy C. Shen Erica Ann Lipasti Our children: Priscilla S. Shen, Rachael S. Shen, and Valentia C. Shen Emma Kristiina Lipasti and Elias Joel Lipasti For information about this book, contact: Waveland Press, Inc. 4180 IL Route 83, Suite 101 Long Grove, IL 60047-9580 (847) 634-0081 info @ waveland.com www.waveland.com Copyright © 2005 by John Paul Shen and Mikko H. Lipasti 2013 reissued by Waveland Press, Inc. 10-digit ISBN 1-4786-0783-1 13-digit ISBN 978-1-4786-0783-0 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Table of Contents PrefaceAbout the Authors x ix 1 Processor Design 1 1.1 The Evolution of Microprocessors 2 1.21.2.1 Instruction Digital Set Systems Processor Design Design 44 1.2.2 Architecture,Realization Implementation, and 5 1.2.3 Instruction Set Architecture 6 1.2.4 Dynamic-Static Interface 8 1.3 Principles of Processor Performance 10 1.3.1 Processor Performance Equation 10 1.3.2 Processor Performance Optimizations 11 1.3.3 Performance Evaluation Method 13 1.4 Instruction-Level Parallel Processing 16 1.4.1 From Scalar to Superscalar 16 1.4.2 Limits of Instruction-Level Parallelism 24 1.51.4.3 Machines Summary for Instruction-Level -

CHERI Concentrate: Practical Compressed Capabilities

1 CHERI Concentrate: Practical Compressed Capabilities Jonathan Woodruff, Alexandre Joannou, Hongyan Xia, Anthony Fox, Robert Norton, Thomas Bauereiss, David Chisnall, Brooks Davis, Khilan Gudka, Nathaniel W. Filardo, A. Theodore Markettos, Michael Roe, Peter G. Neumann, Robert N. M. Watson, Simon W. Moore Abstract—We present CHERI Concentrate, a new fat-pointer compression scheme applied to CHERI, the most developed capability-pointer system at present. Capability fat pointers are a primary candidate to enforce fine-grained and non-bypassable security properties in future computer systems, although increased pointer size can severely affect performance. Thus, several proposals for capability compression have been suggested elsewhere that do not support legacy instruction sets, ignore features critical to the existing software base, and also introduce design inefficiencies to RISC-style processor pipelines. CHERI Concentrate improves on the state-of-the-art region-encoding efficiency, solves important pipeline problems, and eases semantic restrictions of compressed encoding, allowing it to protect a full legacy software stack. We present the first quantitative analysis of compiled capability code, which we use to guide the design of the encoding format. We analyze and extend logic from the open-source CHERI prototype processor design on FPGA to demonstrate encoding efficiency, minimize delay of pointer arithmetic, and eliminate additional load-to-use delay. To verify correctness of our proposed high-performance logic, we present a HOL4 machine-checked proof of the decode and pointer-modify operations. Finally, we measure a 50% to 75% reduction in L2 misses for many compiled C-language benchmarks running under a commodity operating system using compressed 128-bit and 64-bit formats, demonstrating both compatibility with and increased performance over the uncompressed, 256-bit format. -

Intel® 80303 and 80302 I/O Processors

Intel® 80303 and 80302 I/O Processors Specification Update March 2007 Notice: The Intel® 80303 and 80302 I/O Processors may contain design defects or errors known as errata which may cause the product to deviate from published specifications. Current characterized errata are available on request. Order Number: 273355-011US INFORMATIONLegal Lines and Disclaimers IN THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED IN CONNECTION WITH INTEL® PRODUCTS. NO LICENSE, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, BY ESTOPPEL OR OTHERWISE, TO ANY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS IS GRANTED BY THIS DOCUMENT. EXCEPT AS PROVIDED IN INTEL’S TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE FOR SUCH PRODUCTS, INTEL ASSUMES NO LIABILITY WHATSOEVER, AND INTEL DISCLAIMS ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTY, RELATING TO SALE AND/OR USE OF INTEL PRODUCTS INCLUDING LIABILITY OR WARRANTIES RELATING TO FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, MERCHANTABILITY, OR INFRINGEMENT OF ANY PATENT, COPYRIGHT OR OTHER INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHT. Intel products are not intended for use in medical, life saving, life sustaining, critical control or safety systems, or in nuclear facility applications. Intel may make changes to specifications and product descriptions at any time, without notice. Designers must not rely on the absence or characteristics of any features or instructions marked “reserved” or “undefined.” Intel reserves these for future definition and shall have no responsibility whatsoever for conflicts or incompatibilities arising from future changes to them. The information here is subject to change without notice. Do not finalize a design with this information. The products described in this document may contain design defects or errors known as errata which may cause the product to deviate from published specifications. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Delaware

Case 1:14-cv-00377-LPS Document 96 Filed 03/23/15 Page 1 of 73 PageID #: 2291 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE INTEL CORPORATION, ) C.A. No. 14-377 (LPS) (CJB) ) Plaintiff, ) DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL ) v. ) ) FUTURE LINK SYSTEMS, LLC, ) ) Defendant. ) FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT MORRIS, NICHOLS, ARSHT & TUNNELL LLP Jack B. Blumenfeld (#1014) Maryellen Noreika (#3208) 1201 North Market Street P.O. Box 1347 OF COUNSEL: Wilmington, DE 19899 (302) 658-9200 Adam Alper [email protected] KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP [email protected] 555 California Street San Francisco, CA 94194 Attorneys for Plaintiff (415) 439-1400 Michael W. De Vries Tim G. Majors KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP 333 S. Hope Street Los Angeles, CA 90071 (213) 680-8400 Gregory S. Arovas KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP 601 Lexington Avenue New York, NY 10022 (212) 446-4766 Case 1:14-cv-00377-LPS Document 96 Filed 03/23/15 Page 2 of 73 PageID #: 2292 Plaintiff Intel Corporation (“Intel”), for its First Amended Complaint against Defendant Future Link Systems, LLC (“Future Link”), hereby alleges as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. This is an action for declaratory judgment that nine United States patents are not infringed, invalid, licensed, and/or exhausted pursuant to the Declaratory Judgment Act, 28 U.S.C. §§ 2201-02, and the Patent Laws of the United States, 35 U.S.C. § 100 et seq., and for such other relief as the Court deems just and proper. THE PARTIES 2. Plaintiff Intel is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the State of Delaware having its principal place of business at 2200 Mission College Boulevard, Santa Clara, California, 95054. -

A Systematic Approach to Software Peripherals for Embedded Systems Ass

A Systematic Approach to Software Peripherals for Embedded Systems Ass. Prof. D. Lioupis A. Papagiannis D. Psihogiou Computer Technology Institute, 61 Dept. of Computer Engineering & Dept. of Computer Engineering & Riga Feraiou St, Patras, Greece Informatics, Univ. of Patras, Greece Informatics, Univ. of Patras, Greece +3061960359 +3061997750 +3061997750 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT several vendors [2]. Examples of such architectures are The continued growth of microprocessors’ performance and the Motorola’s 68000, Intel’s i960, Sun’s Sparc, Hitachi’s SuperH, need for better CPU utilization, has led to the introduction of the etc. There are two strategies for integrating peripherals on such software peripherals’ approach: By this term we refer to software microprocessors. According to the first strategy, a basic core and modules that can successfully emulate peripherals that, until now, additional logic for a custom device are integrated onto the same were traditionally implemented in hardware. Software die. The second approach uses a standard microprocessor together implementations offer great flexibility in product design and in with a companion chip that serves applications’ specific needs [1]. functional upgrades, while they have high contribution in the These strategies, and especially the first, are leading to chips that cost/performance ratio optimization. We focus on embedded are produced in relatively small volumes due to the fact that they applications, where the cost and the short time to market are the serve only a small range of embedded applications (usually one). leading issues. In this paper, we study the hardware and software Small production volumes are translated in higher final cost. -

Vxworks ® Programmer’S Guide

VxWorks ® Programmer’s Guide 5.4 Edition 1 An ISO 9001 Registered Company Copyright 1984 – 1999 Wind River Systems, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be copied in any form, by photocopy, microfilm, retrieval system, or by any other means now known or hereafter invented without the prior written permission of Wind River Systems, Inc. VxWorks, IxWorks, Wind River Systems, the Wind River Systems logo, wind, and Embedded Internet are registered trademarks of Wind River Systems, Inc. CrossWind, Tornado, VxMP, VxSim, VxVMI, WindC++, WindConfig, Wind Foundation Classes, WindNet, WindPower, WindSh, and WindView are trademarks of Wind River Systems, Inc. All other trademarks used in this document are the property of their respective owners. Corporate Headquarters Europe Japan Wind River Systems, Inc. Wind River Systems, S.A.R.L. Wind River Systems Japan 1010 Atlantic Avenue 19, Avenue de Norvège Pola Ebisu Bldg. 11F Alameda, CA 94501-1153 Immeuble B4, Bâtiment 3 3-9-19 Higashi USA Z.A. de Courtaboeuf 1 Shibuya-ku 91953 Les Ulis Cédex Tokyo 150 FRANCE JAPAN toll free (US): 800/545-WIND telephone: 510/748-4100 telephone: 33-1-60-92-63-00 telephone: 81-3-5467-5900 facsimile: 510/749-2010 facsimile: 33-1-60-92-63-15 facsimile: 81-3-5467-5877 CUSTOMER SUPPORT Telephone E-mail Fax Corporate: 800/872-4977 toll free, U.S. & Canada [email protected] 510/749-2164 510/748-4100 direct Europe: 33-1-69-07-78-78 [email protected] 33-1-69-07-08-26 Japan: 011-81-3-5467-5900 [email protected] 011-81-3-5467-5877 If you purchased your Wind River Systems product from a distributor, please contact your distributor to determine how to reach your technical support organization. -

Test and Integration Environment for PCI Coprocessor Cards

Test and Integration Environment for PCI Coprocessor Cards A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Houston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Electrical Engineering By Mark De Ford August 2001 Test and Integration Environment for PCI Coprocessor Cards Mark De Ford Approved: Chairman of the Committee Martin Herbordt, Associate Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Committee Members: John Glover, Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Jaspal Subhlok, Associate Professor, Computer Science E. J. Charlson, Associate Dean, Fritz Claydon, Professor and Chair Cullen College of Engineering Electrical and Computer Engineering ii Acknowledgements Special thanks and gratitude to my advisor Dr. Martin Herbordt for his guidance and friendship without which this thesis would not be possible. Thanks to Dr. Glover and Dr. Subhlok for serving on my committee. I would also like to extend my heartfelt thanks to my family, friends and coworkers for supporting my educational pursuits all these years. iii Test and Integration Environment for PCI Coprocessor Cards An Abstract of a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Houston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Electrical Engineering By Mark De Ford August 2001 iv Abstract Application specific coprocessor cards are omnipresent in today's high performance computing environment. Computationally intensive applications such as graphics, computer vision, and DNA string matching benefit from the extra computing power supplied by coprocessor cards. This thesis is one aspect of a larger project to implement a high performance SIMD coprocessor card (SCC). -

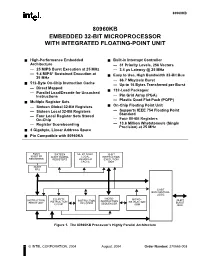

80960Kb Embedded 32-Bit Microprocessor with Integrated Floating-Point Unit

80960KB 80960KB EMBEDDED 32-BIT MICROPROCESSOR WITH INTEGRATED FLOATING-POINT UNIT ■ High-Performance Embedded ■ Built-in Interrupt Controller Architecture — 31 Priority Levels, 256 Vectors — 25 MIPS Burst Execution at 25 MHz — 3.4 µs Latency @ 25 MHz — 9.4 MIPS* Sustained Execution at ■ Easy to Use, High Bandwidth 32-Bit Bus 25 MHz — 66.7 Mbytes/s Burst ■ 512-Byte On-Chip Instruction Cache — Up to 16 Bytes Transferred per Burst — Direct Mapped ■ 132-Lead Packages: — Parallel Load/Decode for Uncached Instructions — Pin Grid Array (PGA) — Plastic Quad Flat-Pack (PQFP) ■ Multiple Register Sets ■ — Sixteen Global 32-Bit Registers On-Chip Floating Point Unit — Sixteen Local 32-Bit Registers — Supports IEEE 754 Floating Point Standard — Four Local Register Sets Stored On-Chip — Four 80-Bit Registers — Register Scoreboarding — 13.6 Million Whetstones/s (Single Precision) at 25 MHz ■ 4 Gigabyte, Linear Address Space ■ Pin Compatible with 80960KA FOUR SIXTEEN 64- BY 32-BIT 32-BIT 80-BIT FP 32-BIT GLOBAL LOCAL INSTRUCTION REGISTERS REGISTERS REGISTER EXECUTION CACHE UNIT 80-BIT FPU 32-BIT BUS CONTROL LOGIC MICRO- INSTRUCTION 512-BYTE MICRO- 32-BIT INSTRUCTION INSTRUCTION INSTRUCTION INSTRUCTION FETCH UNIT DECODER SEQUENCER BURST CACHE ROM BUS Figure 1. The 80960KB Processor’s Highly Parallel Architecture © INTEL CORPORATION, 2004 August, 2004 Order Number: 270565-008 Information in this document is provided in connection with Intel products. No license, express or implied, by estoppel or otherwise, to any intellectual property rights is granted by this document. Except as provided in Intel's Terms and Conditions of Sale for such products, Intel assumes no liability whatsoever, and Intel disclaims any express or implied warranty, relating to sale and/or use of Intel products including liability or warranties relating to fitness for a particular purpose, merchantability, or infringement of any patent, copyright or other intellectual property right.