Speciale__Audun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fællesrådenes Adresser

Fællesrådenes adresser Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail Kirkebakken 23 Beder-Malling-Ajstrup Fællesråd Jørgen Friis Bak [email protected] 8330 Beder Langelinie 69 Borum-Lyngby Fællesråd Peter Poulsen Borum 8471 Sabro [email protected] Holger Lyngklip Hoffmannsvej 1 Brabrand-Årslev Fællesråd [email protected] Strøm 8220 Brabrand Møllevangs Allé 167A Christiansbjerg Fællesråd Mette K. Hagensen [email protected] 8200 Aarhus N Jeppe Spure Hans Broges Gade 5, 2. Frederiksbjerg og Langenæs Fællesråd [email protected] Nielsen 8000 Aarhus C Hastruptoften 17 Fællesrådet Hjortshøj Landsbyforum Bjarne S. Bendtsen [email protected] 8530 Hjortshøj Poul Møller Blegdammen 7, st. Fællesrådet for Mølleparken-Vesterbro [email protected] Andersen 8000 Aarhus C [email protected] Fællesrådet for Møllevangen-Fuglebakken- Svenning B. Stendalsvej 13, 1.th. Frydenlund-Charlottenhøj Madsen 8210 Aarhus V Fællesrådet for Aarhus Ø og de bynære Jan Schrøder Helga Pedersens Gade 17, [email protected] havnearealer Christiansen 7. 2, 8000 Aarhus C Gudrunsvej 76, 7. th. Gellerup Fællesråd Helle Hansen [email protected] 8220 Brabrand Jakob Gade Øster Kringelvej 30 B Gl. Egå Fællesråd [email protected] Thomadsen 8250 Egå Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail [email protected] Nyvangsvej 9 Harlev Fællesråd Arne Nielsen 8462 Harlev Herredsvej 10 Hasle Fællesråd Klaus Bendixen [email protected] 8210 Aarhus Jens Maibom Lyseng Allé 17 Holme-Højbjerg-Skåde Fællesråd [email protected] -

Social Capital in Gellerup

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Journal of social inclusion. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Espvall, M., Laursen, L. (2014) Social capital in Gellerup. Journal of social inclusion, 5(1): 19-42 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:miun:diva-23812 Social capital in Gellerup ___________________________________________ Line Hille Laursen Psychiatric Research Unit West Denmark Majen Espvall Mid-Sweden University Abstract This paper examines the characteristics of two types of social capital; bridging and bonding social capital among the residents inside and outside a marginalized local community in relation to five demographic features of age, gender, geographical origin and years of residence in the community and in Denmark. The data were collected through a questionnaire, conducted in the largest marginalized high-rise community in Denmark, Gellerup, which is about to undergo an extensive community renewal plan. The study showed that residents in Gellerup had access to bonding and bridging social capital inside and outside Gellerup. Nevertheless, the character of the social capital varied considerably depending on age, geographical origin and years lived in Gellerup. Young residents and people who had lived for many years in Gellerup had more social capital than their counterparts. Furthermore, residents from Arab countries had more bonding relations inside Gellerup, while residents from Northern Europe had more bonding relations outside Gellerup. Keywords: Social capital, marginalized communities, Denmark, bonding social capital, bridging social capital Journal of Social Inclusion, 5(1), 2014 Journal of Social Inclusion, 5(1), 2014 Introduction During the 1960s and 1970s, communities of large-scale high-rise housing estates were built in many countries to meet the after-war housing shortage. -

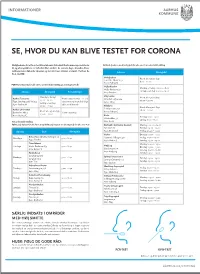

Testmuligheder I Aarhus Kommune

INFORMATIONER SE, HVOR DU KAN BLIVE TESTET FOR CORONA Mulighederne for at få en test bliver løbende forbedret. Der kommer nye teststeder Kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år uden tidsbestilling til, og åbningstiderne er forbedret flere steder i de seneste dage. Desuden bliver testkapaciteten løbende tilpasset og sat ind, hvor smitten er størst. Her kan du Adresse Åbningstid få et overblik: Nobelparken Åbent alle ugens dage Jens Chr. Skous Vej 2 8.00 – 20.00 8000 Aarhus C PCR-Test (I halsen) for alle over 2 år med tidsbestilling på coronaprover.dk Vejlby-Risskov Mandag – fredag: 06.00 – 18.00 Vejlby Centervej 51 Lørdag – søndag: 09.00 – 19.00 Adresse Åbningstid Bemærkninger 8240 Risskov Mandag – fredag: Viby Hallen Aarhus Testcenter Handicapparkering er på Åbent alle ugens dage 07.00 – 21.00 Skanderborgvej 224 Tyge Søndergaards Vej 953 testcentret og man skal følge 08.00 – 20.00 Lørdag – søndag: 8260 Viby J 8200 Aarhus N skiltene til kørende 08.00 – 21.00 Filmbyen Åbent alle ugens dage Aarhus Universitet Filmbyen Studie 1 Åbent alle ugens dage 08.00 – 20.00 Bartholins Allé 3 Handicapvenlig 8000 Aarhus C 09.00 – 16.00 8000 Aarhus C Beder Torsdag: 11:00 - 19:00 Kirkebakken 58 Lørdag: 11:00 - 17:00 Test uden tidsbestilling. 8330 Beder PCR test (i halsen for alle fra 2 år og kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år. Brabrand - Det Gamle Gasværk Mandag: 09.00 – 19.00 Byleddet 2C Tirsdag: 09.00 – 19.00 Ugedag Sted Åbningstid 8220 Brabrand Fredag: 09.00 – 19.00 Harlev Onsdag: 09:00 - 19:00 Beboerhuset Vest’n, Nyringen 1A Mandage 9.00 - 16.30. -

Smagen Af Æbler I Aarhus Som PDF-Fil

SMAGEN AF ÆBLER I AARHUS Smag på Aarhus, Aarhus Kommune, september 2017, revideret 2020 Foto: Anne Louise Madsen (s. 17), Cecilie Lambertsen & Stine Stampe Johansen (s. 18-27) og Aarhus Kommune www.smagpaaaarhus.dk Indhold 5 Æbler i det offentlige rum 6 Find de gode æblesteder i Aarhus 8 Spiseæbler på store gamle træer Æblehaven i Lystrup, Tilst Bypark, Marienlystparken, Frederiksbjerg Bypark, Engdalgårdsparken, Holme Bypark, Sletvej Æbleskov, Ryparken, parken ved Vil- helmsborg, Lerbjergparken, Langenæsparken, Vejlby Torv, Bomgårdshaven i Mårslet og Donbækhuse i Mindeparken 10 Spiseæbler - nye æblesteder Egå Marina, Harlev Æblelund, Vorrevangsparken, Vår- kærparken, Østerby Mose, Æblelunden Skejby, Veste- reng Æblelund, Skovvejens Æblelund, Viby Torv, Chr. Kiers Plads, Lisbjerg Skov, True Skov, Solbjerg Skov, Åbo Skov, Lillehammervej Legeplads 13 Skovæbler og vilde æbler Brabrandstien, Moesgård Strand, Gellerup skov 14 Viden om æbler 16 Modningsskema 17 Opskrifter 3 Skovvejens Æblelund Vil du også plante og passe frugttræer i dit lokalområde, så find inspiration på www.smagpaaaarhus.dk og skriv til [email protected] 4 Æbletræer i det offentlige rum Du må gerne spise æbler af træer, der står på de offentlige arealer, det vil sige langs stier, i parker og i skovene. Flere steder i Aarhus er der rigtig Aarhusianerne har også taget gode spiseæbler i parker og grønne skovlen i egen hånd – og med områder. Det er blandt andet tid- støtte fra Smag på Aarhus – plan- ligere æbleplantager eller æble- tet frugttræer i deres lokalområder haver fra gamle gårde, der på til glæde for fællesskabet. Ved grund af byudviklingen er blevet at påvirke de nære omgivelser er købt af kommunen. -

8 PAPER 1 'Mass Housing and the Emergence of the 'Concrete Slum

PAPER 1 ‘Mass Housing and the Emergence of the ‘Concrete Slum’ in Denmark in the 1970s & 1980s’ by Mikkel Høghøj (School of Culture and Society, Aarhus University, Denmark) Abstract However, in a Danish context studies of how and why modernist mass housing developed from By investigating how modernist mass housing being emblematic of urban modernity in the 1950s was turned into both an ‘object of criticism’ and and 1960s to serving as a prime marker of societal an ‘object of study’ in the 1970s and early 1980s crisis in the 1970s and 1980s are surprisingly few – Denmark, this articles seeks to bring new perspec- especially when considering how contested these tives to the early history of Danish mass housing. places are today. The present article addresses Even though the rejection of urban modernism this research gap by examining two ways in which constitutes a well-established feld of research Danish mass housing was reappraised during internationally, surprisingly few scholars have so the 190s and 0s ore specifcall, analse far investigated how this played out in a Danish how modernist mass housing transformed as a context. This article addresses this research gap particular type of ‘place’ in Danish society by being by analysing how mass housing was portrayed turned into both an ‘object of criticism’ and an and re-evaluated as a ‘place’ in Danish mass ‘object of study’. Yet, in order to explain this trans- media and popular culture as well as within social formation, certain characteristics of the planning scientifc research from the 190s to the mid- and construction of Danish mass housing in the 1980s. -

Urban Youth and Outdoor Spa

Architecture, Design and Conservation Danish Portal for Artistic and Scientific Research Aarhus School of Architecture // Design School Kolding // Royal Danish Academy Urban Youth & Outdoor Space in Gellerup Nielsen, Tom; Terkelsen, Katrine Duus ; Schneidermann, Nanna ; Pedersen, Leo ; Hoehne, Stefan ; Thelle, Mikkel ; Bürk, Thomas ; Nielsen, Morten Publication date: 2015 Link to publication Citation for pulished version (APA): Nielsen, T., Terkelsen, K. D., Schneidermann, N., Pedersen, L., Hoehne, S., Thelle, M., Bürk, T., & Nielsen, M. (2015). Urban Youth & Outdoor Space in Gellerup: URO LAB REPORT #1. Aarhus Universitet. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 Urban Youth & Outdoor Space in Gellerup URO LAB 1 REPORT #1 0 3 INTRODUCTION : 4 Urban orders and the -

Ruteøkonomi for Aarhus Kommune 2011

Ruteøkonomi for Aarhus Kommune 2011 Rute nr. Strækning Kpl.timer Udgifter Indtægter Busselskab Pass. Indt. Erhvervs- Skolekort HyperCard Takst Omstigere Beford Andre Indtægter billetter/kort kort inkl. Komp kompens. Bus&Tog Værnepl Indtægter Total Bybus kørsel Tidligere trafikplan (I ruteøkonomi til og med 31. juli 2011) 1 Tranbjerg - Holmevej - Dalgas Avenue - Banegårdspladsen - Marienlund 17.884 16.627.047 BAAS 3 Hasle - Banegårdspladsen - Christiansbjerg - Skejby - Trige Århus Nord 19.542 16.250.382 BAAS 4 Frydenlund - Mølleparken - Banegårdspladsen - Skåde 13.144 9.032.973 BAAS 5 Stavtrup - Viby Torv - Banegårdspladsen - Åbyhøj - Gl Åby Toveshøj 17.243 14.494.652 BAAS 6 Åkrogen - Marienlund - Banegårdspladsen - Højbjerg - Moesgård Museum 12.239 8.210.456 BAAS 7 Vejlby Nord - Østbanetorvet - Banegårdspladsen - Mølleparken - Charlottehøj 17.988 13.012.314 BAAS 8 Dalgas Avenue - Ringgaden - Marienlund 11.085 8.827.282 BAAS 9 Grøfthøj - Viby Torv - Harald Jensens Plads - Banegårdspladsen - Lystrup Ø V 22.724 20.162.976 BAAS 10 Åbyhøj Nord - Banegårdspladsen - Harald Jensens Plads - Højbjerg - Mårslet 10.508 9.309.593 BAAS 11 Østerby - Tranbjerg - Harald Jensens Plads - Banegårdspladsen - Vejlby Vest 19.444 18.822.576 BAAS 12 Højbjerg - Kridthøjtorvet Skådeparken - Viby - Hasle - Vejlby - Egå Strandvej 21.663 20.691.466 BAAS 14 Skjoldhøj - Bispehaven - Banegårdspladsen - Christiansbjerg - Skejby Sygehus17.185 14.575.971 BAAS 15 Kolt - Harald Jensens Plads - Banegårdspladsen - Gellerup - Brabrand 19.657 17.030.485 BAAS 16 Egå Strandvej - -

Solstråler Over Århus“ Er Syv Ruter, Som Stråler Ud Fra Århus by Som Stråler Fra Solen

På cykel, i løb eller på gåben „Solstråler over Århus“ er syv ruter, som stråler ud fra Århus by som stråler fra solen. Ruterne kobler på en ny måde byen sammen med den fantastiske natur, der omkranser Århus. Tag en tur på solstrålerne – og få unikke naturoplevelser! Pump cyklen, stram løbeskoene eller snør støvlerne – på en solstråletur får du pulsen op og kommer hjem sundere på sjæl og legeme. Læs mere om de enkelte ruter og hent en rutebeskrivelse på www.solstråler.dk. „Solstråler over Århus“ er et projektsamarbejde mellem Natur historisk Museum og Natur og Miljø, Århus Kommune, med økonomisk støtte fra Friluftsrådet. Kystruten (17 km) starter lidt inde i skoven ved Chr. Filtenborgs Plads. Den følger skovveje og cykelstier gennem Marselisborgskoven til Skovmøllen og retur. Kystruten er velegnet til både cykel-, løbe- og gåture. Undervejs kan du bl.a. opleve: Havreballe Skov, som rummer træer fra 1700-tallet. Skovmøllen, om vinteren ses bl.a. vandstær og bjergvipstjert. Ottetals-søen og mosen med spændende botaniske lokaliteter. Ørnereden, en trappe med 124 trin ned til stenstranden. Den blå rute (25 km) følger Århus Å nær byens hjerte ved By museet og ad stisystemet rundt om Brabrand Sø og Årslev Engsø. Ruten er velegnet til både cykel-, løbe- og gåture. Her kan du bl.a. opleve: Århus Å, som tidligere blev brugt til brygning af byens øl. Tre broer, hvor den sjældne bregne, rundfinnet radeløv, vokser. Det gamle pumpehus, som i dag er et informations- og udsigts tårn. Brabrand Sø og Eskelund, interessante naturområder. Bjergruten (8 km) slynger sig i Skjoldhøjkilens grønne korridor til True Skov og tilbage. -

Europe's White Working Class Communities in Aarhus

EUROPE’S WHITE WORKING CLASS COMMUNITIES 1 AARHUS AT HOME IN EUROPE EUROPE’S WHITE WORKING CLASS COMMUNITIES AARHUS OOSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.inddSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.indd CC11 22014.11.06.014.11.06. 118:40:328:40:32 ©2014 Open Society Foundations This publication is available as a pdf on the Open Society Foundations website under a Creative Commons license that allows copying and distributing the publication, only in its entirety, as long as it is attributed to the Open Society Foundations and used for noncommercial educational or public policy purposes. Photographs may not be used separately from the publication. ISBN: 9781940983189 Published by OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS 224 West 57th Street New York NY 10019 United States For more information contact: AT HOME IN EUROPE OPEN SOCIETY INITIATIVE FOR EUROPE Millbank Tower, 21-24 Millbank, London, SW1P 4QP, UK www.opensocietyfoundations.org/projects/home-europe Design by Ahlgrim Design Group Layout by Q.E.D. Publishing Printed in Hungary. Printed on CyclusOffset paper produced from 100% recycled fi bres OOSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.inddSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.indd CC22 22014.11.06.014.11.06. 118:40:348:40:34 EUROPE’S WHITE WORKING CLASS COMMUNITIES 1 AARHUS THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WORK TO BUILD VIBRANT AND TOLERANT SOCIETIES WHOSE GOVERNMENTS ARE ACCOUNTABLE TO THEIR CITIZENS. WORKING WITH LOCAL COMMUNITIES IN MORE THAN 100 COUNTRIES, THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS SUPPORT JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS, FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, AND ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH AND EDUCATION. OOSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.inddSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.indd 1 22014.11.06.014.11.06. 118:40:348:40:34 AT HOME IN EUROPE PROJECT 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements This city report was prepared as part of a series of reports titled Europe’s Working Class Communities. -

Børn Og Unges Fritidsliv I Udsatte Boligområder I Århus

Børn og unges fritidsliv i udsatte boligområder i Århus Det Boligsociale Fællessekretariat Børn og unges fritidsliv i udsatte boligområder i Århus _________________________________________________________________ Udgiver: Det Boligsociale Fællessekretariat Undersøgelsesperiode: marts‐maj 2009 Udgivelse: juni 2009 Rapporten kan rekvireres ved henvendelse til Det Boligsociale Fællessekretariat Saralyst Allé 55 8270 Højbjerg Telefon 8734 0002 fs@fs‐bydele.dk www.bydele.dk Forsidefoto: Gunni Seidelin Det Boligsociale Fællessekretariat er et samarbejde mellem alle almene boligforeninger i Århus. Fællessekretariatet blev etableret i 2007 med det formål at koordinere og styrke den boligsociale indsats i de udsatte boligområder i Århus. Se mere om Fællessekretariatet på www.bydele.dk 2 Børn og unges fritidsliv i udsatte boligområder i Århus _________________________________________________________________ Resumé Børn og unge fylder meget i de udsatte boligområder rundt omkring i landet og således også i Århus. I de udsatte boligområder i Århus er lidt over en tredjedel af beboerne børn og unge under 18 år, mens det kun gælder for hver femte beboer i Århus som helhed. Med de mange børn og unge er der behov for et godt fritidsliv med mange forskellige aktivitetstilbud. Spørgsmålet er imidlertid, hvordan fritidslivet i de udsatte boligområder ser ud. På baggrund af en undersøgelse af omfanget og brugen af kommunale og foreningsbaserede fritidstilbud til børn og unge i Viby Syd, Bispehaven, Herredsvang og Gellerup/Toveshøj, konkluderer denne rapport, at fritidslivet i de udsatte boligområder har nogle mangler. Overordnet set tegner undersøgelsen et billede af, at de eksisterende tilbud i områderne kun opfanger en mindre del af børnene og de unge. Med et svagt foreningsliv i områderne og en række barrierer for brug af eksterne foreningstilbud er fritidslivet i områderne i høj grad knyttet op på de kommunale fritids‐ og ungdomsklubber. -

Aarhus Letbane, Etape 2

Aarhus Letbane, etape 2. Den planlagte rute går fra Aarhus Ø gennem Hovedbanegården og en del af midtbyen op ad Viborgvej gennem Hasle Torv til Gellerupparken med endestation i Brabrand eller Aarslev Ruten er ikke længere tidssvarende. For lange rejsetider i midtbyen Efter vores mening er denne rute ikke længere Toget skal tilpasse sig trafikkens hastighed inde i tidssvarende, fordi den er overhalet indenom af byen, og man regner med 15 – 30 km/time. Skal den kraftige byfortætning langs Søren Frichs Vej en borger foretage et skift mellem etape 1 og eta- og Godsbaneterrænet, den ændrede bebyggelse pe 2 skal han ind i midtbyen, hvor hastigheden er og anvendelse i Gellerupparken samt de spæn- så lav, at rejsetiden bliver alt for lang. Det giver så dende højteknologiske muligheder, som nærhe- lange rejsetider, at mange potentielle brugere vil den af Universitetshospitalet i Skejby kan tilbyde. fravælge letbanen. Høje udgifter i de centrale dele af Aarhus Gør ikke nok for yderområderne Km prisen for etape 2 varierer mellem 70 mio. kr. Ruten fastholder Aarhus midtby som den centrale pr. km for strækninger over åbent land til 180 mio. del af byen. Det er måske et ønske – men det er kr. pr. km for strækninger i den centrale del af ikke hensigtsmæssigt. Skal en borger transporte- Aarhus. res fra eksempelvis Skejby Sygehus til Gellerup- Ud over etableringen på ca. 1240 millioner kr. sy- parken, skal han hele vejen ind omkring midtbyen. nes det at koste omkring 655 millioner kroner eks- De lange rejsetider mellem yderområderne ind- tra at ændre diverse ledningssystemer i jorden iflg. -

Dear Muslims in the City of Aarhus the Residential Ghetto Policy Targets You - and It (Awaits) Behind the Fight Against Social Problems (Translated)

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم Dear Muslims in the City of Aarhus The Residential Ghetto Policy Targets You - and it (Awaits) Behind the Fight Against Social Problems (Translated) It is not new for the Danish government to pursue a policy of discrimination against Muslims; successive governments launched what they called the war of values against Islam, and the Parliament has enacted many laws directed against Muslims at various levels. This has happened over the past twenty years. In the same vein, the integration policy has been applied, and it is in fact an assimilation policy that has been integrated with the security policy. As for non-Western immigrants and their descendants; meaning Muslims in their political definition, they are the ones who pose a security and cultural threat, and they are the burden in economic terms! With the city of Aarhus as an advanced model for the Danish government, housing policy has become part of this campaign. With the launch of the “ghetto” campaign in 2018, it was emphasized that the criterion used for considering a neighborhood as a "ghetto" is to be a concentration area for residents of non-Western backgrounds. This criterion is a stigma for the residents, and opens the door wide for initiatives based on discrimination that have disastrous consequences for human lives. One such consequence is the forced eviction of residents, as well as obliging parents to send their young children to kindergartens. The ghetto plan was launched as part of the so-called war of values, in conjunction with the launch of a hostile discourse in which terms such as parallel society and "holes in the map of Denmark" were used, where Danish values had no sovereignty.