EPDF Polaris Interior.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cosmology and Shamanism and Shamanism INTERVIEWING INUIT ELDERS

6507.3 Eng Cover w/spine/bleed 5/1/06 9:23 AM Page 1 INTERVIEWINGCosmology INUIT ELDERS and Shamanism Cosmology and Shamanism INTERVIEWING INUIT ELDERS Mariano and Tulimaaq Aupilaarjuk, Lucassie Nutaraaluk, Rose Iqallijuq, Johanasi Ujarak, Isidore Ijituuq and Michel Kupaaq 4 Edited by Bernard Saladin d’Anglure 6507.5_Fre 5/1/06 9:11 AM Page 239 6507.3 English Vol.4 5/1/06 9:21 AM Page 1 INTERVIEWING INUIT ELDERS Volume 4 Cosmology and Shamanism Mariano and Tulimaaq Aupilaarjuk, Lucassie Nutaraaluk, Rose Iqallijuq, Johanasi Ujarak, Isidore Ijituuq and Michel Kupaaq Edited by Bernard Saladin d’Anglure 6507.3 English Vol.4 5/1/06 9:21 AM Page 2 Interviewing Inuit Elders Volume 4 Cosmology and Shamanism Copyright © 2001 Nunavut Arctic College, Mariano and Tulimaaq Aupilaarjuk, Bernard Saladin d’Anglure and participating students Susan Enuaraq, Aaju Peter, Bernice Kootoo, Nancy Kisa, Julia Saimayuq, Jeannie Shaimayuk, Mathieu Boki, Kim Kangok, Vera Arnatsiaq, Myna Ishulutak, and Johnny Kopak. Photos courtesy Bernard Saladin d’Anglure; Frédéric Laugrand; Alexina Kublu; Mystic Seaport Museum. Louise Ujarak; John MacDonald; Bryan Alexander. Illustrations courtesy Terry Ryan in Blodgett, ed. “North Baffin Drawings,” Art Gallery of Ontario; 1923 photo of Urulu, Fifth Thule Expedition. Cover illustration “Man and Animals” by Lydia Jaypoody. Design and production by Nortext (Iqaluit). All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without written consent of the publisher is an infringement of the copyright law. ISBN 1-896-204-384 Published by the Language and Culture Program of Nunavut Arctic College, Iqaluit, Nunavut with the generous support of the Pairijait Tigummivik Elders Society. -

Addressing Gendered Violence Against Inuit Women: a Review of Police Policies and Practices in Inuit Nunangat

Addressing Gendered Violence against Inuit Women: A review of police policies and practices in Inuit Nunangat Full Report & Recommendations Pauktuutit Inuit Women Canada and Dr. Elizabeth Comack Department of Sociology and Criminology University of Manitoba January 31, 2020 pauktuutit.ca A REVIEW OF POLICE POLICIES AND PRACTICES IN INUIT NUNANGAT Contents Acknowledgements . .3 The Report in Brief . .4 Gendered Violence against Inuit Women . .10 Basic Demographics . .11 Framing the Issue: Locating Gendered Violence in the Colonial Context . .12 Pre-contact . .13 Early Contact . .14 Life in the Settlements . .16 The Role of the RCMP in the Colonial Encounter . .17 Into the Present . .22 The “Lived Experience” of Colonial Trauma . .24 Contemporary Policing in Inuit Nunangat . .27 RCMP Policies and Protocols . .27 RCMP Detachments . .29 The First Nations Policing Policy . .29 Policing in Nunavik: the Kativik Regional Police Force . .30 Policing Challenges . .32 Methodology . .35 Policing In Inuvialuit . .38 Safety Concerns and Gendered Violence . .38 Police Presence . .40 Community Policing: Set up to fail? . .40 Racism or Cultural Misunderstanding? . .43 Calling the Police for Help . .45 Responding when Domestic Violence Occurs . .46 The “Game within the Game” . .48 What Needs to be Done? . .51 Healing and Resilience . .54 Policing in Nunavut . .57 Police Presence . .58 The Police Response . .59 Racialized Policing . .60 “Don’t Trust the Cops” . .61 Normalizing Gendered Violence . .63 Policing Challenges . .64 High Turnover of Officers . .65 Inuit Officers . .66 The Language Disconnect . .68 The Housing Crisis . .69 What Needs to be Done? . .70 PAUKTUUTIT INUIT WOMEN OF CANADA 1 ADDRESSING GENDERED VIOLENCE AGAINST INUIT WOMEN Policing in Nunatsiavut . -

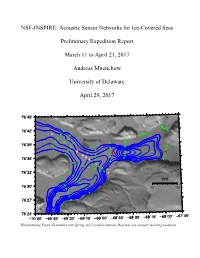

Expedition Report

NSF-INSPIRE: Acoustic Sensor Networks for Ice-Covered Seas Preliminary Expedition Report March 11 to April 21, 2017 Andreas Muenchow University of Delaware April 29, 2017 . 76˚45' − −50 76˚42' 100 Manson Is. 76˚39' −100 −50 −100 −50 150 −100 − 76˚36' −50 76˚33' 150 − km km 76˚30' 0 5 0 10 −150 −200 76˚27' 76˚24' −68˚00' −67˚45' −70˚00' −69˚45' −69˚30' −69˚15' −69˚00' −68˚45' −68˚30' −68˚15' Wolstenholme Fjord, Greenland with Spring 2017 science stations. Red dots are acoustic mooring locations. 1. Introduction The US National Science Foundation (NSF) funded a project to “design and develop an integrated underwater acoustic sensor network for ice-covered seas.” Wolstenholme Fjord adjacent to Thule Air Base (TAB) in Greenland was identified to test and deploy this communication network to provide a real-time data connection between a remote transmit and a coastal receive unit via several data hops from modem to modem. The envisioned system shares features of a cell phone network where data passes from caller to receiver via cell phone towers. The fjord is covered by land-fast sea ice during spring and thus provides a stable platform from which to test, deploy, and recover a range of oceanographic and acoustic sensor systems via snowmobiles during day-light hours when air temperatures are generally above -25°C. During the first phase from Mar.-11 through Mar.-25 we conducted ice thickness surveys, placed an automated weather station (AWS) on the sea ice along with a provisional shelter and deployed an oceanographic thermistor mooring in water 110 m deep at the center of the study area. -

Canada's Arctic Marine Atlas

Lincoln Sea Hall Basin MARINE ATLAS ARCTIC CANADA’S GREENLAND Ellesmere Island Kane Basin Nares Strait N nd ansen Sou s d Axel n Sve Heiberg rdr a up Island l Ch ann North CANADA’S s el I Pea Water ry Ch a h nnel Massey t Sou Baffin e Amund nd ISR Boundary b Ringnes Bay Ellef Norwegian Coburg Island Grise Fiord a Ringnes Bay Island ARCTIC MARINE z Island EEZ Boundary Prince i Borden ARCTIC l Island Gustaf E Adolf Sea Maclea Jones n Str OCEAN n ait Sound ATLANTIC e Mackenzie Pe Ball nn antyn King Island y S e trait e S u trait it Devon Wel ATLAS Stra OCEAN Q Prince l Island Clyde River Queens in Bylot Patrick Hazen Byam gt Channel o Island Martin n Island Ch tr. Channel an Pond Inlet S Bathurst nel Qikiqtarjuaq liam A Island Eclipse ust Lancaster Sound in Cornwallis Sound Hecla Ch Fitzwil Island and an Griper nel ait Bay r Resolute t Melville Barrow Strait Arctic Bay S et P l Island r i Kel l n e c n e n Somerset Pangnirtung EEZ Boundary a R M'Clure Strait h Island e C g Baffin Island Brodeur y e r r n Peninsula t a P I Cumberland n Peel Sound l e Sound Viscount Stefansson t Melville Island Sound Prince Labrador of Wales Igloolik Prince Sea it Island Charles ra Hadley Bay Banks St s Island le a Island W Hall Beach f Beaufort o M'Clintock Gulf of Iqaluit e c n Frobisher Bay i Channel Resolution r Boothia Boothia Sea P Island Sachs Franklin Peninsula Committee Foxe Harbour Strait Bay Melville Peninsula Basin Kimmirut Taloyoak N UNAT Minto Inlet Victoria SIA VUT Makkovik Ulukhaktok Kugaaruk Foxe Island Hopedale Liverpool Amundsen Victoria King -

Shipwreck at Cape Flora: the Expeditions of Benjamin Leigh Smith, England’S Forgotten Arctic Explorer

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2013 Shipwreck at Cape Flora: The Expeditions of Benjamin Leigh Smith, England’s Forgotten Arctic Explorer Capelotti, P. J. University of Calgary Press Capelotti, P.J. "Shipwreck at Cape Flora: The Expeditions of Benjamin Leigh Smith, England’s Forgotten Arctic Explorer". Northern Lights Series No. 16. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2013. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49458 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com SHIPWRECK AT CAPE FLORA: THE EXPEDITIONS OF BENJAMIN LEIGH SMITH, ENGLAND’S FORGOTTEN ARCTIC EXPLORER P.J. Capelotti ISBN 978-1-55238-712-2 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

The Effects of Incentives and Organizational Structure

The Effects of Incentives and Organizational Structure Jonathan M. Karpoff Independent Institute Working Paper Number 23 June 2000 100 Swan Way, Oakland, CA 94621-1428 • 510-632-1366 • Fax: 510-568-6040 • Email: [email protected] • http://www.independent.org Public Versus Private Initiative in Arctic Exploration: The Effects of Incentives and Organizational Structure Jonathan M. Karpoff Norman J. Metcalfe Professor of Finance School of Business University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195 206-685-4954 [email protected] First draft: January 6, 1999 Third revision: January 24, 2000 I thank Peter Conroy for research assistance, and Helen Adams, George Benston, Mike Buesseler, Harry DeAngelo, Linda DeAngelo, Wayne Ferson, Alan Hess, Charles Laird, Paul Malatesta, John Matsusaka, Dave Mayers, Harold Mulherin, Jeff Netter, Jeff Pontiff, Russell Potter, Ed Rice, Sherwin Rosen, Sunil Wahal, Ralph Walkling, Mark White, an anonymous referee, and participants at seminars at the 1999 Arizona Finance Conference, the University of Alabama, University of British Columbia, Emory University, University of Georgia, University of Southern California, Texas A&M University, and the University of Washington for helpful comments. Public Versus Private Initiative in Arctic Exploration: The Effects of Incentives and Organizational Structure Abstract From 1818 to 1909, 35 government and 57 privately-funded expeditions sought to locate and navigate a Northwest Passage, discover the North Pole, and make other significant discoveries in arctic regions. Most major arctic discoveries were made by private expeditions. Most tragedies were publicly funded. By other measures as well, publicly-funded expeditions performed poorly. On average, 5.9 (8.9%) of their crew members died per outing, compared to 0.9 (6.0%) for private expeditions. -

Locked in Ice and While Drifting North, They Discovered the Archipelago They Named Franz Josef Land After the Austro-Hungarian Emperor

After Matter 207-74305_ch01_6P.indd 253 11/22/18 9:40 AM Second lieutenant Sigurd Scott-Hansen, who was responsible for the meteorological, astronomical, and magnetic observations on the expedition, turned out to be a good photographer. 207-74305_ch01_6P.indd 254 11/22/18 9:40 AM Appendix • The Design of the Fram • The Crew of the Fram • Duties of the Crew Aboard • Science Aboard the Fram • Full List of Nansen’s Equipment for the Two- Man Dash to the North Pole • A List of Nansen’s Dogs on Starting the Trek to the North Pole • Dogs and Polar Exploration • North Pole Expeditions and Rec ords of Farthest North • A Special Note on Geoff Carroll and a Modern- Day Sled Dog Trip to the North Pole • Navigating in the Arctic • Explanation of Navigating at the North Pole, by Paul Schurke • Simple Use of the Sun and a 24- Hour Watch, by Geoff Carroll • Time Line • Glossary 207-74305_ch01_6P.indd 255 11/22/18 9:40 AM 207-74305_ch01_6P.indd 256 11/22/18 9:40 AM The Design of the Fram ANSEN OBSERVED THAT many Arctic explorers never N really gave much thought to their boats but took what was available. He felt that the success of the Fram Expedition depended on having the right ship built for the ice. For living quarters, a series of small cabins opened up to the saloon, where eating and social activity took place. The Fram had four single cabins, one each for Nansen, Sverdrup, Scott- Hansen, and Dr. Blessing. Two larger cabins housed either four men or five: Amundsen, Pettersen, Juell, and Johansen shared one, and Mogstad, Bentsen, Jacobsen, Nordahl, and Hendriksen were cramped together. -

Shipwreck at Cape Flora: the Expeditions of Benjamin Leigh Smith, England’S Forgotten Arctic Explorer

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2013 Shipwreck at Cape Flora: The Expeditions of Benjamin Leigh Smith, England’s Forgotten Arctic Explorer Capelotti, P. J. University of Calgary Press Capelotti, P.J. "Shipwreck at Cape Flora: The Expeditions of Benjamin Leigh Smith, England’s Forgotten Arctic Explorer". Northern Lights Series No. 16. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2013. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49458 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com SHIPWRECK AT CAPE FLORA: THE EXPEDITIONS OF BENJAMIN LEIGH SMITH, ENGLAND’S FORGOTTEN ARCTIC EXPLORER P.J. Capelotti ISBN 978-1-55238-712-2 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Nasjonsrelaterte Stedsnavn På Svalbard Hvilke Nasjoner Har Satt Flest Spor Etter Seg? NOR-3920

Nasjonsrelaterte stedsnavn på Svalbard Hvilke nasjoner har satt flest spor etter seg? NOR-3920 Oddvar M. Ulvang Mastergradsoppgave i nordisk språkvitenskap Fakultet for humaniora, samfunnsvitenskap og lærerutdanning Institutt for språkvitenskap Universitetet i Tromsø Høsten 2012 Forord I mitt tidligere liv tilbragte jeg to år som radiotelegrafist (1964-66) og ett år som stasjonssjef (1975-76) ved Isfjord Radio1 på Kapp Linné. Dette er nok bakgrunnen for at jeg valgte å skrive en masteroppgave om stedsnavn på Svalbard. Seks delemner har utgjort halve mastergradsstudiet, og noen av disse førte meg tilbake til arktiske strøk. En semesteroppgave omhandlet Norske skipsnavn2, der noen av navna var av polarskuter. En annen omhandlet Språkmøte på Svalbard3, en sosiolingvistisk studie fra Longyearbyen. Den førte meg tilbake til øygruppen, om ikke fysisk så i hvert fall mentalt. Det samme har denne masteroppgaven gjort. Jeg har også vært student ved Universitetet i Tromsø tidligere. Jeg tok min cand. philol.-grad ved Institutt for historie høsten 2000 med hovedfagsoppgaven Telekommunikasjoner på Spitsbergen 1911-1935. Jeg vil takke veilederen min, professor Gulbrand Alhaug for den flotte oppfølgingen gjennom hele prosessen med denne masteroppgaven om stedsnavn på Svalbard. Han var også min foreleser og veileder da jeg tok mellomfagstillegget i nordisk språk med oppgaven Frå Amarius til Pardis. Manns- og kvinnenavn i Alstahaug og Stamnes 1850-1900.4 Jeg takker også alle andre som på en eller annen måte har hjulpet meg i denne prosessen. Dette gjelder bl.a. Norsk Polarinstitutt, som velvillig lot meg bruke deres database med stedsnavn på Svalbard, men ikke minst vil jeg takke min kjære Anne-Marie for hennes tålmodighet gjennom hele prosessen. -

Investigation of Radioactive Contamination

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 01, 2021 Thule-2003 - Investigation of radioactive contamination Nielsen, Sven Poul; Roos, Per Publication date: 2006 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Nielsen, S. P., & Roos, P. (2006). Thule-2003 - Investigation of radioactive contamination. Risø National Laboratory. Denmark. Forskningscenter Risoe. Risoe-R No. 1549(EN) General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Risø-R-1549(EN) Thule-2003 - Investigation of Radioactive Contamination Sven P. Nielsen and Per Roos Risø National Laboratory Roskilde Denmark May 2006 Author: Sven P. Nielsen and Per Roos Risø-R-1549(EN) May 2006 Title: Thule-2003 – Investigation of Radioactive Contamination Department: Radiation Research Abstract ISSN 0106-2840 ISBN 87-550-3508-6 Analyses of marine and terrestrial samples collected in August 2003 from Bylot Sound at Thule, Northwest Greenland, show that plutonium from nuclear weapons in the American B52 plane, which crashed on the sea ice in January 1968, persists in the environment. -

A Note on the Depots of the 1897 Andrée Balloon Expedition

Polar Record A note on the depots of the 1897 Andrée balloon www.cambridge.org/pol expedition Björn Lantz Research Note Technology Management and Economics, Chalmers University of Technology, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden Cite this article: Lantz B (2019). A note on the Abstract depots of the 1897 Andrée balloon expedition. Polar Record 55:48–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/ Recent research suggests that the members of the 1897 Andrée balloon expedition could have S0032247419000159 survived if they had marched towards the depot at Seven Islands instead of the Cape Flora depot after the forced landing at 82°56’N 29°52’E, and furthermore, that they reasonably should have Received: 31 January 2019 done so given what they knew about the ice drift in the area. This paper comprises an analysis of Revised: 14 March 2019 ’ ’ Accepted: 15 March 2019 the expedition s depots based on a review of original sources, and the results elucidate Andrée s initial decision to march towards Cape Flora. The Seven Island depot was not yet laid when Keywords: Andrée departed in his balloon, and the information he had at the time indicated that it Andrée balloon expedition; Arctic exploration; was highly uncertain that depot could be laid at all. Moreover, he knew it might be difficult Depots; Seven Islands; Cape Flora to find the depot even if it had been laid since no exact position for it could be determined Author for correspondence: Björn Lantz, in advance. If he arrived at the Seven Islands without being able to obtain supplies there, Email: [email protected] Andrée knew he would have to continue all the way to Nordenskiöld’s old hut in Mossel Bay. -

Thule-2003 - Investigation of Radioactive Contamination

Risø-R-1549(EN) Thule-2003 - Investigation of Radioactive Contamination Sven P. Nielsen and Per Roos Risø National Laboratory Roskilde Denmark May 2006 Author: Sven P. Nielsen and Per Roos Risø-R-1549(EN) May 2006 Title: Thule-2003 – Investigation of Radioactive Contamination Department: Radiation Research Abstract ISSN 0106-2840 ISBN 87-550-3508-6 Analyses of marine and terrestrial samples collected in August 2003 from Bylot Sound at Thule, Northwest Greenland, show that plutonium from nuclear weapons in the American B52 plane, which crashed on the sea ice in January 1968, persists in the environment. The highest concentrations of plutonium are found in the marine sediments under the location where the plane crashed. The distribution of plutonium in the marine sediment is very inhomogeneous and associated with hot particles with Group's own reg. no.: 239,240 1400102-02 activities found up to 1500 Bq Pu. Sediment samples collected in Wolstenholme Fjord north of the accident site show plutonium concentrations, which illustrates the Sponsorship: Ministry of the Environment redistribution of plutonium after the accident. The total plutonium inventory in the sediments has been assessed based on systematic analyses considering hot particles. The inventory of 239,240Pu in the sediments within a distance of 17 km from the point of impact of the B52 plane is estimated at 2.9 TBq (1 kg). Earlier estimates of the inventory were approximately 1.4 TBq 239,240Pu. Seawater and seaweed samples show increased concentrations of plutonium in Bylot Sound. The increased concentrations are due to resuspension of plutonium- containing particles from the seabed and transport further away from the area.