On Weapons Plutonium in the Arctic Environment (Thule, Greenland)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baffin Bay Sea Ice Extent and Synoptic Moisture Transport Drive Water Vapor

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 13929–13955, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-13929-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Baffin Bay sea ice extent and synoptic moisture transport drive water vapor isotope (δ18O, δ2H, and deuterium excess) variability in coastal northwest Greenland Pete D. Akers1, Ben G. Kopec2, Kyle S. Mattingly3, Eric S. Klein4, Douglas Causey2, and Jeffrey M. Welker2,5,6 1Institut des Géosciences et l’Environnement, CNRS, 38400 Saint Martin d’Hères, France 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alaska Anchorage, 99508 Anchorage, AK, USA 3Institute of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Rutgers University, 08854 Piscataway, NJ, USA 4Department of Geological Sciences, University of Alaska Anchorage, 99508 Anchorage, AK, USA 5Ecology and Genetics Research Unit, University of Oulu, 90014 Oulu, Finland 6University of the Arctic (UArctic), c/o University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland Correspondence: Pete D. Akers ([email protected]) Received: 9 April 2020 – Discussion started: 18 May 2020 Revised: 23 August 2020 – Accepted: 11 September 2020 – Published: 19 November 2020 Abstract. At Thule Air Base on the coast of Baffin Bay breeze development, that radically alter the nature of rela- (76.51◦ N, 68.74◦ W), we continuously measured water va- tionships between isotopes and many meteorological vari- por isotopes (δ18O, δ2H) at a high frequency (1 s−1) from ables in summer. On synoptic timescales, enhanced southerly August 2017 through August 2019. Our resulting record, flow promoted by negative NAO conditions produces higher including derived deuterium excess (dxs) values, allows an δ18O and δ2H values and lower dxs values. -

Expedition Report

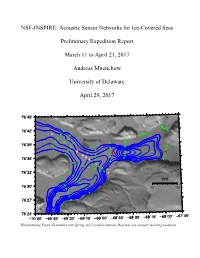

NSF-INSPIRE: Acoustic Sensor Networks for Ice-Covered Seas Preliminary Expedition Report March 11 to April 21, 2017 Andreas Muenchow University of Delaware April 29, 2017 . 76˚45' − −50 76˚42' 100 Manson Is. 76˚39' −100 −50 −100 −50 150 −100 − 76˚36' −50 76˚33' 150 − km km 76˚30' 0 5 0 10 −150 −200 76˚27' 76˚24' −68˚00' −67˚45' −70˚00' −69˚45' −69˚30' −69˚15' −69˚00' −68˚45' −68˚30' −68˚15' Wolstenholme Fjord, Greenland with Spring 2017 science stations. Red dots are acoustic mooring locations. 1. Introduction The US National Science Foundation (NSF) funded a project to “design and develop an integrated underwater acoustic sensor network for ice-covered seas.” Wolstenholme Fjord adjacent to Thule Air Base (TAB) in Greenland was identified to test and deploy this communication network to provide a real-time data connection between a remote transmit and a coastal receive unit via several data hops from modem to modem. The envisioned system shares features of a cell phone network where data passes from caller to receiver via cell phone towers. The fjord is covered by land-fast sea ice during spring and thus provides a stable platform from which to test, deploy, and recover a range of oceanographic and acoustic sensor systems via snowmobiles during day-light hours when air temperatures are generally above -25°C. During the first phase from Mar.-11 through Mar.-25 we conducted ice thickness surveys, placed an automated weather station (AWS) on the sea ice along with a provisional shelter and deployed an oceanographic thermistor mooring in water 110 m deep at the center of the study area. -

Sir John Franklin and the Arctic

SIR JOHN FRANKLIN AND THE ARCTIC REGIONS: SHOWING THE PROGRESS OF BRITISH ENTERPRISE FOR THE DISCOVERY OF THE NORTH WEST PASSAGE DURING THE NINE~EENTH CENTURY: WITH MORE DETAILED NOTICES OF THE RECENT EXPEDITIONS IN SEARCH OF THE MISSING VESSELS UNDER CAPT. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN WINTER QUARTERS IN THE A.ROTIO REGIONS. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN AND THE ARCTIC REGIONS: SHOWING FOR THE DISCOVERY OF THE NORTH-WEST PASSAGE DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: WITH MORE DETAILED NOTICES OF THE RECENT EXPEDITIONS IN SEARCH OF THE MISSING VESSELS UNDER CAPT. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN. BY P. L. SIMMONDS, HONORARY AND CORRESPONDING JIIEl\lBER OF THE LITERARY AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF QUEBEC, NEW YORK, LOUISIANA, ETC, AND MANY YEARS EDITOR OF THE COLONIAL MAGAZINE, ETC, ETC, " :Miserable they Who here entangled in the gathering ice, Take their last look of the descending sun While full of death and fierce with tenfold frost, The long long night, incumbent o•er their heads, Falls horrible." Cowl'ER, LONDON: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & CO., SOHO SQUARE. MDCCCLI. TO CAPT. SIR W. E. PARRY, R.N., LL.D., F.R.S., &c. CAPT. SIR JAMES C. ROSS, R.N., D.C.L., F.R.S. CAPT. SIR GEORGE BACK, R.N., F.R.S. DR. SIR J. RICHARDSON, R.N., C.B., F.R.S. AND THE OTHER BRAVE ARCTIC NAVIGATORS AND TRAVELLERS WHOSE ARDUOUS EXPLORING SERVICES ARE HEREIN RECORDED, T H I S V O L U M E I S, IN ADMIRATION OF THEIR GALLANTRY, HF.ROIC ENDURANCE, A.ND PERSEVERANCE OVER OBSTACLES OF NO ORDINARY CHARACTER, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, BY THEIR VERY OBEDIENT HUMBLE SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. -

Sheep Farming As “An Arduous Livelihood”

University of Alberta Cultivating Place, Livelihood, and the Future: An Ethnography of Dwelling and Climate in Western Greenland by Naotaka Hayashi A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology ©Naotaka Hayashi Spring 2013 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract In order to investigate how Inuit Greenlanders in western Greenland are experiencing, responding to, and thinking about recent allegedly human-induced climate change, this dissertation ethnographically examines the lives of Greenlanders as well as Norse and Danes in the course of past historical natural climate cycles. My emphasis is on human endeavours to cultivate a future in the face of difficulties caused by climatic and environmental transformation. I recognize locals’ initiatives to carve out a future in the promotion of sheep farming and tree-planting in southern Greenland and in adaptation processes of northern Greenlandic hunters to the ever-shifting environment. -

NKS-215, Assessment of Weathering and Leaching Rates of Thule Hot

Nordisk kernesikkerhedsforskning Norrænar kjarnöryggisrannsóknir Pohjoismainen ydinturvallisuustutkimus Nordisk kjernesikkerhetsforskning Nordisk kärnsäkerhetsforskning Nordic nuclear safety research NKS-215 ISBN 978-87-7893-285-3 Assessment of weathering and leaching rates of Thule hot particles Per Roos (1) Iisa Outola (2) Ulrika Nygren (3) Henrik Ramebäck (3) Rajdeep Sidhu (4) (1)Risoe National Laboratory for Sustainable Energy Technical University of Denmark (2)STUK-Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority, Finland (3)FOI CBRN Defence and Security, Sweden (4)Environmental Monitoring Section, Health and Safety Department Institute of Energy Technology, Norway March 2010 Abstract Within the current project a methodology for separating actinide particles originating from the Thule 1968 accident has been developed. Particles were completely isolated in water using visual and radiometric methods. The particles were attached electrostatic to a plastic support and could easily be moved to any container for leaching studies or other type of studies. Leaching and dissolution studies performed within the project indicate that some particles are relatively easily destroyed or leached while others are more refractory. The results shows that even though the oxide particles are hard to completely dissolve they release material even when exposed to weak solvents like water and salt solutions. Exposures to lung simulant fluids show relatively slow dissolution rates comparable to what is found using only water. Sequential extraction of particles shows that variation between particles is very large; some dissolve easily while some does not. Of radiological importance is the disruption of particles when exposed to dissolution. Key words Thule, actinide particles, hot particles, plutonium, uranium, Pu-239, U-235, leaching, lung simulant fluid, stomach simulant fluid NKS-215 ISBN 978-87-7893-285-3 Electronic report, March 2010 NKS Secretariat NKS-776 P.O. -

EPDF Polaris Interior.Indd

T9 W B 2 e PolarisChief Scientist’s Recollections of the American North Pole Expedition, 1871–73 Emil Bessels 2 Polaris NORTHERN LIGHTS SERIES Copublished with the Arctic Institute of North America issn 1701-0004 (print) issn 1925-2943 (online) This series takes up the geographical region of the North (circumpolar regions within the zone of discontinuous permafrost) and publishes works from all areas of northern schol- arship, including natural sciences, social sciences, earth sciences, and the humanities. No. 1 · Nunavik: Inuit-Controlled Education in Arctic Quebec Ann Vick-Westgate · Copublished with the Katutjiniq Regional Development Council No. 2 · Many Faces of Gender: Roles and Relationships through Time in Northern Indigenous Communities Edited by Lisa Frink, Rita S. Shepard, and Gregory A. Reinhardt · Copublished with University Press of Colorado No. 3 · New Owners in their Own Land: Minerals and Inuit Land Claims Robert McPherson No. 4 · War North of 80: The Last German Arctic Weather Station of World War II Wilhelm Dege, translated and edited by William Barr · Copublished with University Press of Colorado No. 5 · Writing Geographical Exploration: Thomas James and the Northwest Passage 1631–33 Wayne K.D. Davies No. 6 · As Long as This Land Shall Last: A History of Treaty 8 and Treaty 11, 1870–1939 René Fumoleau No. 7 · Breaking Ice: Renewable Resource and Ocean Management in the Canadian North Edited by Fikret Berkes, Rob Huebert, Helen Fast, Micheline Manseau, and Alan Diduck No. 8 · Alliance and Conflict: The World System of the Inupiaq Eskimos Ernest S. Burch · Copublished with the University of Nebraska Press No. -

ROLF Gilbergl Numerous Place Names in Greenland Are Beset With

Thule ROLF GILBERGl Numerous place names in Greenland are beset with some confusion, and Thule is possibly the most nonspecific of them all. An attempt has been made in the following paper, therefore, to set out some of the various meanings which have been attached to the word. ULTIMATHULE In times of antiquity, “Thule” was the name given to an archipelago far to the north of the Scandinavian seas.The Greek explorer Pytheas told his contemporaries about this far-awayplace, and about the year 330 B.C.he sailed northward from Marseilles in France in search of the source of amber. When he reached Britain, heheard of an archipelagofurther north known as “Thule”.The name was apparently Celtic;the archipelago what are now known as the Shetland Isles. AfterPytheas’ time, the ancientscalled Scandinavia “Thule”. In poetry,it became“Ultima Thule”, i.e. “farthest Thule”, a distantnorthern place, geo- ‘ graphically undefined and shrouded in esoteric mystery. As the frontiers of man’s exploration gradually expanded, the legendary Ultima Thule acquired a more northerly location. It moved with the Vikings from the Faroe Islands to Iceland, and, when Iceland was colonized in the ninth century A.D., Greenland became “Thule” in folklore. THULESTATION Perhap Knud Rasmussen had these historical facts in mind when he founded a trading post in 1910 among the Polar Eskimos and called the store “Thule Station”. The committee managing Rasmussen’s station was, incidentally, always referred to as the Cape York Committee, and the official name of the station was “Cape York Station, Thule”. Behind the pyramid-shaped base of the rock called Mount Dundas by British explorers, but generally known as Thule Mountain, on North Star Bay, the best natural harbour in the area, the Polar Eskimos hadplaced their settlement, Umanaq (meaning heart-shaped). -

S16-P16 Radiation in the Environment

Contents Session 16: Radiation in the environment S16 Oral presentations S16-01 Regularities of long-term changes in artificial radionuclides content in the Barents Sea ecosystem . 2337 Matishov, Gennady; Matishov Dmitry; Solatie Dina; Kasatkina Nadezda; Leppänen Ari-Pekka S16-02 Human dose pathways from forests contaminated by atmospheric radionuclide deposition . 2345 Rantavaara, Aino; Ammann, Michael S16-03 Occurrence of plutonium in the terrestrial environment at Thule, Greenland . 2356 Roos, Per; Jernström, Jussi; Nielsen, Sven P. S16-04 Environmental radioactivity assessment at nuclear legacy sites in the Republic of Tajikistan (ABSTRACT) . 2362 Nalbandyan, Anna; Hosseini, Ali S16-05 Improved model for estimation of fallout from atmospheric nuclear testing (ABSTRACT) . 2363 Pálsson, Sigurdur Emil; Howard, Brenda J.; Ikäheimonen, Tarja K.; Nielsen, Sven P. S16-06Y Reduction of radioxenon emissions from radiopharmaceutical facilities – A pilot study . 2364 Braekers, Damien; Camps, Johan; Paridaens, Johan; Saey, Paul R. J.; van der Meer, Klaas S16-07Y Public exposure by natural radionuclides in drinking water – Models for effective dose assessment and implications to guidelines . 2374 Gruber, Valeria; Maringer, Franz Josef Third European IRPA Congress 2010, Helsinki, Finland Contents Topic 16: Radiation in the environment P16 Poster presentations P16-01 Impact of facilities under the nuclear fuel cycle on the public health: SUE “Hydro Metallurgical Plant” (LPO “ALMAZ”) case study . 2383 Titov, A. V.; Tukov, A. R.; Bogdanova, L. S.; Yatsenko, V. N.; Korzinkin, M. B. P16-02 Modelling with a CFD code the near-range dispersion of particles unexpectedly released from a nuclear power plant . 2392 Gallego, Eduardo; Barbero, Rubén; Cuadra, Daniel; Domingo, Jerónimo; Iranzo, Alfredo P16-03 Inspection Plan for the detection of contamination at a Nuclear Fuel Cycle facility . -

Investigation of Radioactive Contamination

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 01, 2021 Thule-2003 - Investigation of radioactive contamination Nielsen, Sven Poul; Roos, Per Publication date: 2006 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Nielsen, S. P., & Roos, P. (2006). Thule-2003 - Investigation of radioactive contamination. Risø National Laboratory. Denmark. Forskningscenter Risoe. Risoe-R No. 1549(EN) General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Risø-R-1549(EN) Thule-2003 - Investigation of Radioactive Contamination Sven P. Nielsen and Per Roos Risø National Laboratory Roskilde Denmark May 2006 Author: Sven P. Nielsen and Per Roos Risø-R-1549(EN) May 2006 Title: Thule-2003 – Investigation of Radioactive Contamination Department: Radiation Research Abstract ISSN 0106-2840 ISBN 87-550-3508-6 Analyses of marine and terrestrial samples collected in August 2003 from Bylot Sound at Thule, Northwest Greenland, show that plutonium from nuclear weapons in the American B52 plane, which crashed on the sea ice in January 1968, persists in the environment. -

Marin Recipientundersøgelse Ved Thule Air Base 2002

Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Miljøministeriet Marin recipientundersøgelse ved Thule Air Base 2002 Faglig rapport fra DMU, nr. 449 [Tom side] Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Miljøministeriet Marin recipientundersøgelse ved Thule Air Base 2002 Faglig rapport fra DMU, nr. 449 2003 Christian M. Glahder Gert Asmund Philipp Mayer Pia Lassen Jakob Strand Frank Riget Datablad Titel: Marin recipientundersøgelse ved Thule Air Base 2002 Forfattere: Christian M. Glahder1, Gert Asmund1, Philipp Mayer2, Pia Lassen2, Jakob Strand3 & Frank Riget1 Afdelinger: 1 Afdeling for Arktisk Miljø 2 Afdeling for Miljøkemi og Mikrobiologi 3 Afdeling for Marin Økologi Serietitel og nummer: Faglig rapport fra DMU nr. 449 Udgiver: Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Miljøministeriet, URL: http://www.dmu.dk Udgivelsestidspunkt: Juli 2003 Redaktionen afsluttet: Juli 2003 Faglig kommentering: Poul Johansen & Jesper Madsen Finansiel støtte: Nærværende rapport er finansieret af Miljøministeriet via programmet for Miljøstøtte til Arktis. Rapportens resultater og konklusioner er forfatternes egne og afspejler ikke nødvendigvis Mil- jøministeriets holdninger. Bedes citeret: Glahder, C. M., Asmund, G., Mayer, P., Lassen, P., Strand, J. & Riget, F. 2003: Marin recipien- tundersøgelse ved Thule Air Base 2002. Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser. 126 s. -Faglig rapport fra DMU nr. 449. http://faglige-rapporter.dmu.dk Gengivelse tilladt med tydelig kildeangivelse. Sammenfatning: I 2002 gennemførte Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser en recipientundersøgelse ud for Thule Air Base (TAB) for at vurdere, om aktiviteterne og specielt de efterladte dumpe på TAB har belastet det marine miljø med forurenende stoffer. Undersøgelsen viser, at der findes flere forurenings- kilder som f. eks. affaldsdumpe, som bevirker at niveauet af enkelte kontaminanter er forhøjet i området ved TAB. Undersøgelsen viser imidlertid også, at denne påvirkning er lokal inden for et nærområde på omkring 5-10 km fra TAB. -

Thule-2003 - Investigation of Radioactive Contamination

Risø-R-1549(EN) Thule-2003 - Investigation of Radioactive Contamination Sven P. Nielsen and Per Roos Risø National Laboratory Roskilde Denmark May 2006 Author: Sven P. Nielsen and Per Roos Risø-R-1549(EN) May 2006 Title: Thule-2003 – Investigation of Radioactive Contamination Department: Radiation Research Abstract ISSN 0106-2840 ISBN 87-550-3508-6 Analyses of marine and terrestrial samples collected in August 2003 from Bylot Sound at Thule, Northwest Greenland, show that plutonium from nuclear weapons in the American B52 plane, which crashed on the sea ice in January 1968, persists in the environment. The highest concentrations of plutonium are found in the marine sediments under the location where the plane crashed. The distribution of plutonium in the marine sediment is very inhomogeneous and associated with hot particles with Group's own reg. no.: 239,240 1400102-02 activities found up to 1500 Bq Pu. Sediment samples collected in Wolstenholme Fjord north of the accident site show plutonium concentrations, which illustrates the Sponsorship: Ministry of the Environment redistribution of plutonium after the accident. The total plutonium inventory in the sediments has been assessed based on systematic analyses considering hot particles. The inventory of 239,240Pu in the sediments within a distance of 17 km from the point of impact of the B52 plane is estimated at 2.9 TBq (1 kg). Earlier estimates of the inventory were approximately 1.4 TBq 239,240Pu. Seawater and seaweed samples show increased concentrations of plutonium in Bylot Sound. The increased concentrations are due to resuspension of plutonium- containing particles from the seabed and transport further away from the area. -

Archaeology of the Polar Eskimo

ANTHROPOLOGICAL1 PAPERS OF TaHE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL 'HISTrORY VOL. XXII, PART III ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE POLAR ESKIMO BY CLARK WISSLER NEW YORK PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES 1918 ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE POLAR ESKIMO. BY CLARK WISSLER. 105 PREFACE. The objects upon which this study is based are from the archaeological collections made by members of the Crocker Land Expedition of the Ameri- can Museum of Natural History, 1913-1918. The sites represented are in the main on the shores of Northeast Greenland, which in historic times were occupied by a group of Eskimo known in America as Smith Sound Eskimo and in Denmark as the Polar Eskimo. The writer was not a mem- ber of the expedition, but represents the anthropological staff of this Mu- seum, in whose custody the collections were placed. He is not, therefore, familiar with the characteristics of the sites from which these objects come and can treat them only as objective examples of Eskimo culture. As such, they offer some suggestive contributions to Eskimo anthropology. The members of the expedition, particularly Doctor Edmund Otis Hovey, geologist of the Museum, Mr. Donald B. MacMillan, the leader of the Expedition, and Captain George Comer, well known to students of the Eskimo for his former contributions, all gave the greatest assistance in the preparation of these pages. The pen drawings were made by William Baake and the plans and map by S. Ichikawa. CLARK WISSLER. June, 1918. 107 CONTENTS. PAGE. PREFACE 107 INTRODUCTION *. ~111 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE LOCALITY 113 EXCAVATIONS IN COMER'S MIDDEN 114 THE AGE OF THE DEPOSIT 114 METHODS OF WORKING BONE AND IVORY 117 KNIVES 120 ULU OR WOMAN'S KNIFE 132 WHETSTONES 137 SPOKE SHAVES 137 SNOW KNIVES 137 THE ADZE 140 ICE PICKS 142 HAMMERS ' .