Arv Nordic Yearbook of Folklore 2014 2 3 ARVARV Nordic Yearbook of Folklore Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heikki Har Blick För Österbotten

katternö1 • 2021 EttEtt österbottnisktösterbottniskt magasinmagasin Sjuttonde årgången När Norge erövrade Finland EU-bråk om ”grön” energi Heikki har blick för Österbotten Till kunderna hos Esse Elektro-Kraft, Herrfors, Kronoby Elverk, Nykarleby Kraftverk Viltkameran – så här gör du och Vetelin Energia. katternö – 1 debatt Taxonomiförslag Vilken är den vackraste Tre frågor... Innehåll i fantasivärld platsen i Österbotten? Linus Lindholm NINA LIDFORS, ETT SÄTT ATT ta sig an problemlösning är att klassifi cera problemet Osmo Nissinen, Emelie Wärn, tidigare rektor för i någon av grupperna a) enkla system, b) komplicerade system och c) Ylivieska Larsmo Vasa övningsskola, kaotiska system. Vasa! Det är en levande I Wärnum, Esse, där jag är tillträdde 2009 I enkla system hittas kända och verifi erade orsak/verkan-samband och vacker sommarstad, uppvuxen. Det ligger längs som rektor i Sve- för alla delproblem som ingår i helheten. mycket tack vare närheten Esse å och det är mycket rige för den då nya I kaotiska system fi nns ingen känd kunskap som kan användas, och till havet. Jag besöker Vasa vackert och lugnt där. En Gripsholmsskolan. metodiken är vanligen massvis med tester. I takt med att samband fl era gånger per år och annan bra sak med Wär- Grundarna trodde kan verifi eras, kan nya tester utföras allt mer strukturerat, och på så känner staden mycket väl num är att jag vet vem alla på den fi nländska sätt kan en lösningsmodell för helheten byggas upp. efter att tidigare ha stude- är. Mina föräldrar bor kvar pedagogiken. 30 av Komplicerade system är en blandning av a och c. rat och arbetat där i fyra där och jag återvänder skolans i dag om- Uppvärmningen av vår planet kan kategoriseras som ett komplice- år. -

Uppföljning Av Livskvalitet 2040 Jakobstadsregionens Strukturplan

Uppföljning av Livskvalitet 2040 Jakobstadsregionens strukturplan 2019 Boende & Fritid Nära – Befolkningsförändringar 2017-2018 Bosund Bef. Ändr Tätort 2018 1 år Näs Jakobstad 18 892 -0,6 % Holm Nykarleby 3 293 -0,1 % Kronoby Sandsund 1 934 -1,0 % Risöhäll- Risöhäll- Nedervetil 1 599 2,8 % Furuholmen Furuholmen Jakobstad Ytteresse 1 398 -0,7 % Kronoby 1 365 0,7 % Sandsund Edsevö Holm 1 070 2,3 % Ytteresse 1 054 0,9 % Bennäs Bosund Kållby Esse Kållby 954 0,0 % Terjärv 893 1,2 % Nykarleby Esse 670 -2,2 % Purmo Terjärv Bennäs 641 0,2 % Nedervetil 573 1,8 % Lillby Jeppo 502 -2,3 % Munsala Edsevö 472 0,2 % 425 3,2 % Näs Jeppo Lillby 329 -1,5 % Munsala 264 0,4 % Purmo 245 0,0 % Lepplax 62 -4,6 % Forsby 45 4,7 % Nära – zonen har på ett år minskat med -32 personer. Källa: YKR/SYKE & TK 2019. Nära – Befolkningsförändringar 2013-2018 Bosund Bef. Ändr Tätort 2018 5 år Näs Jakobstad 18 892 -2,1 % Holm Nykarleby 3 293 0,6 % Kronoby Sandsund 1 934 5,5 % Risöhäll- Risöhäll- Nedervetil 1 599 6,7 % Furuholmen Furuholmen Jakobstad Ytteresse 1 398 -3,2 % Kronoby 1 365 0,5 % Sandsund Edsevö Holm 1 070 9,5 % Ytteresse 1 054 5,2 % Bennäs Bosund Kållby Esse Kållby 954 1,6 % Terjärv 893 0,1 % Nykarleby Esse 670 -2,3 % Purmo Terjärv Bennäs 641 -0,2 % Nedervetil 573 -1,4 % Lillby Jeppo 502 -4,0 % Munsala Edsevö 472 -1,0 % 425 -2,5 % Näs Jeppo Lillby 329 -2,4 % Munsala 264 -1,9 % Purmo 245 1,7 % Lepplax 62 -11,4 % Forsby 45 -8,2 % Nära – zonen har på fem år minskat med -131 personer. -

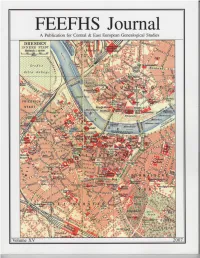

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

Deteljplanebeskr-Ntil.Pdf

Kommun Kronoby kommun Dokument Detaljplanebeskrivning Datum 31.5.2016 KRONOBY KOMMUN REVIDERING OCH UTVIDGNING AV NEDERVETIL DE- TALJPLAN REVIDERING OCH UTVIDGNING AV NEDERVETIL DETALJPLAN 2 REVIDERING OCH UTVIDGNING AV NEDERVETIL DETALJPLAN DETALJPLANEBESKRIVNING Författare Christoffer Rönnlund Datum 31.5.2016 Granskare Jonas Lindholm Granskad 31.5.2016 Ramboll Hovrättsesplanaden 19 E 65100 VASA T +358 20 755 7600 F +358 20 755 7602 www.ramboll.fi 1-2 INNEHÅLLSFÖRTECKNING 1. BAS- OCH IDENTIFIKATIONSUPPGIFTER 4 1.1 Identifikationsuppgifter 4 1.2 Detaljplaneområdets läge 4 1.3 Planens namn och syfte 6 1.4 Förteckning över bilagor till beskrivningen 6 2. SAMMANDRAG 6 2.1 Olika skeden i detaljplaneprocessen 6 2.2 Detaljplanen 6 2.3 Genomförandet av detaljplanen 7 3. UTGÅNGSPUNKTERNA 7 3.1 Utredning om förhållandena på detaljplaneområdet 7 3.1.1 Allmän beskrivning av området 7 3.1.2 Naturmiljön 7 3.1.3 Den byggda miljön 11 3.1.4 Markägoförhållanden 22 3.2 Planeringssituationen 22 3.2.1 Planer, beslut och utredningar som berör detaljplaneområdet 22 3.2.1.1 De riksomfattande målen för områdesanvändningen 22 3.2.1.2 Landskapsplanen 22 3.2.1.2.1 Etapplandskapsplan 1 24 3.2.1.2.2 Etapplandskapsplan 2 25 3.2.1.3 Generalplan 25 3.2.1.4 Gällande detaljplan 25 3.2.1.5 Byggnadsordningen 26 3.2.1.6 Tomtindelning och tomtregister 26 3.2.1.7 Baskarta 26 3.3 Generalplanegranskning 27 4. OLIKA SKEDEN I PLANERINGEN AV DETALJPLANEN 29 4.1 Behovet av detaljplanering 30 4.2 Planeringsstart och beslut som gäller denna 30 4.3 Deltagande och samarbete 30 4.3.1 Intressenter 30 4.3.2 Anhängiggörande 31 4.3.3 Deltagande och växelverkan 31 4.3.4 Myndighetssamarbete 31 5. -

Kommunistskräck, Konservativ Reaktion Eller Medveten Bondepolitik? | 2012 Konservativ Johanna Bonäs | Kommunistskräck

Johanna Bonäs | Kommunistskräck, konservativ bondepolitik? | 2012 eller medveten reaktion Johanna Bonäs Johanna Bonäs Kommunistskräck, konservativ reaktion Kommunistskräck, eller medveten bondepolitik? Svenskösterbottniska bönder inför Lapporörelsen sommaren 1930 konservativ reaktion eller medveten bonde- politik? Svenskösterbottniska bönder inför Lapporörelsen sommaren 1930 Lapporörelsen var den enskilt största av alla de anti- kommunistiska högerrörelser som verkade i Finland under mellankrigstiden. Också på den svenskös- terbottniska landsbygden uppstod en lappovänlig front sommaren 1930. I denna lokal- och till vissa delar mikrohistoriska studie presenteras nya förkla- ringar utöver viljan att stoppa kommunismen till att bönderna på den svenskösterbottniska lands- bygden tog ställning för Lapporörelsen genom att delta i bondetåget till Helsingfors i juli och genom att förespråka så kallade fosterländska valförbund inför riksdagsvalet i oktober. 9 789517 656566 Åbo Akademis förlag | ISBN 978-951-765-656-6 Foto:Bildström Johanna Bonäs (f. 1976) Filosofi e magister 2002, inom utbildningsprogrammet för nordisk historia inom fakultetsområdet för humaniora, pedagogik och teologi (Åbo Akademi). Sedan år 2003 arbetar Johanna som lärare och lärarutbildare i historia och samhällslära vid Vasa övningsskola. Hon har under den tiden varit involverad i agrarhistoriska forskningsprojekt och bland annat skrivit en historik över Österbottens svenska lantbrukssällskap. Hon har även varit medförfattare till läroböcker i historia för grundskolan. Åbo -

P> LARSMOLARSMO LUOTOLUOTO

LARSMOLARSMO LUOTOLUOTO Larsmo !c Luoto !kmt3 JAKOBSTADJAKOBSTAD c Kronoby PIETARSAARIPIETARSAARI ! Kruunupyy Nedervetil !ca Alaveteli JAKOBSTAD PIETARSAARI C Kållby !ca Kolppi KRONOBYKRONOBY Bennäs !c Pännäinen KRUUNUPYYKRUUNUPYY Esse !ca Ähtävä NYKARLEBY UUSIKAARLEPYY C PEDERSÖRE ca Terjärv NYKARLEBYNYKARLEBY PEDERSÖRE ! Teerijärvi UUSIKAARLEPYYUUSIKAARLEPYY !ca Purmo-Lillby !ca Munsala Jeppo !ca Jepua KORSHOLMKORSHOLM MUSTASAARIMUSTASAARI Oravais !c Oravainen VÖRÅVÖRÅ VÖYRIVÖYRI Replot !ca Raippaluoto Maxmo !ca Maksamaa !ca Karperö ca Kvevlax ! Koivulahti !ca Gerby ! ! ! ! ! ! ! km2 ! ! ! ! Smedsby Vörå ! ! ! ! ! ! ! c ! c ! m Sepänkylä ! Vöyri VAASA ! k !! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! VASA ! ! ! ! ! Huutoniemi ! ! ! VAASAVAASA ! C Roparnäs ! ! VASAVASA ! ! !ca ! ! ! ! Ristinummi ! ! ! ca ! ! Korsnäståget km! t1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Merikaarto km3 Vanha-Vaasa ! !ca Merikart !ca Gamla Vasa VAASAVAASA !!LM VASA at 1 VASA !- !km4 !!L1M !ca Sundom ! Vähäkyrö !c Lillkyro !p kmt3 Solf ! !ca Sulva MALAXMALAX MAALAHTIMAALAHTI !ca Tervajoki !kmt2 !p Isokyrö !c Storkyro Laihia !c Laihela Malax !c Maalahti ISOKYRÖISOKYRÖ STORKYROSTORKYRO LAIHIALAIHIA LAIHELALAIHELA Petalax !ca Petolahti Beteckningar för utvecklingsprinciper, KORSNÄSKORSNÄS områdesreserveringar och objektsbeteckningar !c Korsnäs Kehittämisperiaatemerkinnät, aluevaraus- ja kohdemerkinnät !! !! !! !! !! !! !! Vasa-Korsholm centrumutvecklingszon - !! !! !! !! !! !! !! !! Vaasan-Mustasaaren keskustakehitysvyöhyke Utvecklingsriktning - Kehityssunta Pörtom C Område för centrumfunktioner - Keskustatoimintojen -

Nedervetil Skyddskr

++Tillvarataget En summa penningar har upphittats mellan Rimmi och Storå växelplats i Gamlakarleby. Återfås på beskrivning hos Hugo Gustafsson i Nedervetil (Öb 02.07-20 Stöld i Nedervetil Natten mot senaste lördag begicks inbrott i Alex Pajunens gård i närheten av Pelo i Nedervetil. Mannen var borta och hustrun sov i ett rum intill kammaren. Tjuven hade berett sig tillträde till kammaren, där han undersökt byrålådor, sängar, mm, samt vänt upp och ned på allting. Bytet blev 310 mk penningar som gårdsfolket "för säkerhetsskull" hade gömda i en korg under en säng samt kostymkläder. Sedan stölden upptäckts tillkallades polis, som dock förlorade spåren, varför tjuven tillsvidare icke kunnat ertappas. (Öb 20.07-20) Rivna får I Nedervetil har den senaste tiden en mängd får, tillhörande olika hemmansägare, rivits av främmande hundar under det de varit på bete mellan Pelo och Lahnakoski. De flesta av fåren har blivit så illa tilltygade, att de äro fullkomligt obrukbara, varför ägarna göra kännbar förlust. (Öb 20.07-20) Nedervetil skyddskår Skidtävlan 05.03-21 20 km A. Brännkärr 1.26 E. Wiik 1.26,17 L. Brännkärr 1.29,40 E. Ahlskog 1.29,50 J.E. Högbacka 1.35 J. Nygren 1.40 15 km J. Simonsbacka 1.07,35 F. Slotte 1.07,44 J. Nyman 1.11,44 E. Nygren 1.11,50 F. Gustafsson 1.13,10 T. Brännkärr 1.13,33 E. Ås 1.14,40 E. Slotte 1.17, 10 km (Juniorer) T. Slotte 45.23 T. Kaino 45.30 T. Hästbacka 45.30,5 O. Pelo 46.47 F. -

District 107 O.Pdf

Club Health Assessment for District 107 O through May 2021 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater report in 3 more than of officers thatin 12 months within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not haveappears in two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active red Clubs more than two years old 20734 ALAVIESKA 12/11/1973 Active 18 1 1 0 0.00% 18 8 0 N 0 M,VP,MC,SC 29140 ESSE 04/10/1974 Active(1) 16 0 1 -1 -5.88% 17 31 1 2 N 24 VP 20598 GAMLAKARLEBY 03/28/1954 Active 34 0 0 0 0.00% 34 1 N 6 M,SC 20735 HAAPAJÄRVI 11/09/1967 Active(1) 23 1 4 -3 -11.54% 29 9 0 N 0 39194 HAAPAJÄRVI/KANTAPUHTO 12/12/1980 Active 20 0 1 -1 -4.76% 21 3 0 N 11 $1,053.00 SC 58187 HAAPAJÄRVI/KULTAHIPUT 04/30/1996 Active 18 2 0 2 12.50% 17 0 N 0 20736 HAAPAVESI 11/16/1969 Active 15 1 2 -1 -6.25% 16 26 0 N 5 M,SC 34124 HALSUA 06/24/1977 Active 21 0 1 -1 -4.55% 22 43 1 N 1 $170.00 M,MC,SC 20739 HIMANKA 03/27/1968 Active 16 0 0 0 0.00% 17 1 N 24+ $1,250.00 M,MC,SC 20603 JAKOBSTAD 11/11/1953 Active 25 0 0 0 0.00% 25 1 N 17 20604 JAKOBSTAD/MALM 01/17/1965 Active -

Österbotten I Siffror Pohjanmaa Lukuina 2016 Ostrobothnia in Numbers

ÖSTERBOTTEN I SIFFROR POHJANMAA LUKUINA 2016 OSTROBOTHNIA IN NUMBERS Kaskinen - Kaskö Korsnäs Isokyrö - Storkyro Larsmo - Luoto Malax - Maalahti Kronoby - Kruunupyy Vörå - Vöyri Kristinestad - Kristiinankaupunki Nykarleby - Uusikaarlepyy Laihia - Laihela Närpes - Närpiö Pedersöre Korsholm - Mustasaari Jakobstad - Pietarsaari Vaasa - Vasa Folkmängd – Väkiluku – Population 2000-2015 Förändring 2000- Muutos 2000 2014 2015 2015 Change % Isokyrö - Storkyrö 5 151 4 842 4 785 -366 -7,1 Kaskinen - Kaskö 1 564 1 324 1 285 -279 -17,8 Korsnäs 2 246 2 219 2 201 -45 -2,0 Kristinestad - Kristiinankaupunki 8 084 6 845 6 793 -1 291 -16,0 Kronoby - Kruunupyy 6 846 6 662 6 682 -164 -2,4 Laihia - Laihela 7 414 8 068 8 090 676 9,1 Larsmo - Luoto 4 111 5 107 5 147 1 036 25,2 Malax - Maalahti 5 638 5 573 5 545 -93 -1,6 Korsholm - Mustasaari 16 614 19 287 19 302 2 688 16,2 Närpes - Närpiö 9 769 9 389 9 387 -382 -3,9 Pedersöre 10 258 11 060 11 129 871 8,5 Jakobstad - Pietarsaari 19 636 19 577 19 436 -200 -1,0 Nykarleby - Uusikaarlepyy 7 492 7 533 7 564 72 1,0 Vaasa - Vasa 61 470 66 965 67 619 6 149 10,0 Vörå - Vöyri 6 935 6 705 6 714 -221 -3,2 Österbotten – Pohjanmaa – Ostrobothnia 173 228 181 156 181 679 8 451 4,9 HELA LANDET – KOKO MAA –WHOLE COUNTRY 5 181 115 5 471 753 5 487 308 306 193 5,9 Tilastokeskus-Statistikcentralen-Statistics Finland Statistikcentralens befolkningsprognos (2015) Tilastokeskuksen väestöennuste (2015) Statistics Finland´s population projection (2015) Förändring Muutos Change % 2015 2030 2040 2015-2040 2015-2040 Uusimaa - Nyland 1 620 -

Travellers, Easter Witches and Cunning Folk: Regulators of Fortune and Misfortune in Ostrobothnian Folklore in Finland

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 14 (1): 121–139 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2020-0008 TRAVELLERS, EASTER WITCHES AND CUNNING FOLK: REGULATORS OF FORTUNE AND MISFORTUNE IN OSTROBOTHNIAN FOLKLORE IN FINLAND KAROLINA KOUVOLA Doctoral Student Department of Culture / Study of Religions University of Helsinki P.O. Box 59 (Unionkatu 38E) 00014 Helsinki, Finland e-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT This article* is about the distinct groups that practised malevolent and benevolent witchcraft in Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia in late-modern Finland according to belief legends and memorates. Placing belief legends and memorates in Mary Douglas’ tripartite classification of powers that regulate fortune and misfortune illuminates the social structure of agents who posed a threat or regulated it by means of their supranormal powers. Powers that bring misfortune dwell outside or within the community, whereas powers that bring fortune live within it but nevertheless may be ambivalent and pose a threat to its members as well. Threat towards the community was based on the concept of limited good, in other words the belief that there was a finite amount of prosperity in the world. The aim is to paint a detailed picture of the complex social structure and approaches to witch- craft in late-modern Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia. KEYWORDS: witchcraft • cunning folk • folk healing • folk belief • benevolent magic INTRODUCTION This article concerns the folklore of the Swedish-speaking minority in late-modern Ostrobothnia, Finland, the aim being to study how various users of witchcraft were understood within the context of limited good in this Swedish-speaking community. I suggest that Mary Douglas’ (2002 [1966]: 130) notion of a triad of power that controls fortune and misfortune in a community facilities the drawing of three distinct groups * I wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on an earlier version of this article and Joan Nordlund for her help with language revision. -

Club Health Assessment MBR0087

Club Health Assessment for District 101 M through April 2021 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater report in 3 more than of officers thatin 12 months within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not haveappears in two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active red Clubs more than two years old 18406 ALFTA 01/22/1973 Active 17 1 1 0 0.00% 17 30 0 2 VP,MC,SC N/R 18356 ÅMÅL 01/14/1955 Active 2 0 4 -4 -66.67% 6 49 1 M,VP,MC,SC N/R 18360 ARBOGA 10/22/1951 Active 22 2 2 0 0.00% 22 2 0 N SC N/R 18358 ÅRJÄNG 11/12/1957 Cancelled(6*) 0 0 22 -22 -100.00% 22 22 1 None P,S,T,M,VP 24+ MC,SC 18359 ARVIKA 01/17/1956 Active 19 2 2 0 0.00% 19 22 0 N MC 16 18361 ASKERSUND 01/26/1960 Active 27 0 0 0 0.00% 25 5 2 R MC,SC 24 18408 AVESTA 12/28/1951 Active 28 0 2 -2 -6.67% 30 5 1 N MC,SC 4 18409 BERGSJÖ 09/01/1969 Active 20 0 2 -2 -9.09% 22 47 0 N MC,SC 16 18411 BORLÄNGE 05/28/1953 Active 24 0 2 -2 -7.69% 26 1 1 N MC,SC 8 46841 BORLÄNGE STORA TUNA 01/07/1987 Active 17 1 0 1 6.25% 16 0 N MC,SC 24+ 18362 DEGERFORS 03/15/1956 Active 15 0 0 0 0.00% -

KOELAJI 372598 TEILERI TIMO KRUUNANTIE 5A 65230 VAASA

KOELAJI 372598 TEILERI TIMO KRUUNANTIE 5a 65230 VAASA 0505659655 AGI 710092 VIRTANEN ANDERS JUTVÄGEN 33 68600 JAKOBSTAD 50525 1232 AGI 191758 ALAVAINIO ERKKI ÅSVÄGEN 220 64220 YTTERMARK 050-371 1673 AJOK 445709 BACKA TORE SÖDRA LARSMOVÄGEN 355 68570 LARSMO 050-526 0917 AJOK 716328 BONDEGÅRD KIM ÖJESVÄGEN 131 68910 BENNÄS 050 581 4810 AJOK 445893 ELENIUS GÖRAN SINGSBYVÄGEN 3a 65280 VASA 0400360527 AJOK 4068252 FELLMAN KJELL TÄHDENLENTO 10 66900 NYKARLEBY 040-5684606 AJOK 410602 LAPPI JUHANI KUNINKAANTIE 58 AS 6 65320 VAASA 500 160 413 AJOK 411496 LIND GUSTAV EGNAHEMSVÄGEN 2 65450 SOLF 050 307 1466 AJOK 772357 MYLLÄRI SVEN-ÅKE LAPLOMVÄGEN 91 66270 PÖRTOM 040 594 4082 AJOK 417699 RIF ERIK LABBVÄGEN 19 68630 JAKOBSTAD 050 322 9649 AJOK 253024 SAARENMÄKI SIMO NYGÅRDSBAKINTIE 10 66600 VÖYRI 044-342 3624 AJOK 452772 SMEDS INGMAR SKEPPARNÄSTÅET 33 A 66240 PETALAX 050-528 4184 AJOK 420401 SUNDFORS ROLAND SJÖBACKAVÄGEN 47 68410 NEDERVETIL 044 785 1224 AJOK 191758 ALAVAINIO ERKKI ÅSVÄGEN 220 64220 YTTERMARK 050-371 1673 BEAJ 445709 BACKA TORE SÖDRA LARSMOVÄGEN 355 68570 LARSMO 050-526 0917 BEAJ 716328 BONDEGÅRD KIM ÖJESVÄGEN 131 68910 BENNÄS 050 581 4810 BEAJ 445893 ELENIUS GÖRAN SINGSBYVÄGEN 3a 65280 VASA 0400360527 BEAJ 4068252 FELLMAN KJELL TÄHDENLENTO 10 66900 NYKARLEBY 040-5684606 BEAJ 410602 LAPPI JUHANI KUNINKAANTIE 58 AS 6 65320 VAASA 500 160 413 BEAJ 411496 LIND GUSTAV EGNAHEMSVÄGEN 2 65450 SOLF 050 307 1466 BEAJ 772357 MYLLÄRI SVEN-ÅKE LAPLOMVÄGEN 91 66270 PÖRTOM 040 594 4082 BEAJ 417699 RIF ERIK LABBVÄGEN 19 68630 JAKOBSTAD 050 322 9649