Anthropogenic Impacts on Cave-Roosting Bats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fruit Bats As Natural Foragers and Potential Pollinators in Fruit Orchard: a Reproductive Phenological Study

Journal of Agricultural Research, Development, Extension and Technology, 25(1), 1-9 (2019) Full Paper Fruit bats as natural foragers and potential pollinators in fruit orchard: a reproductive phenological study Camelle Jane D. Bacordo, Ruffa Mae M. Marfil and John Aries G. Tabora Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Southern Mindanao, Kabacan, Cotabato, Philippines Received: 27 February 2019 Accepted: 10 June 2019 Abstract Family Pteropodidae could consume either fruit or flower parts to sustain their energy requirement. In some species of fruit bats, population growth is sometimes dependent on the food availability and in return bats could be pollinators of certain species of plants. In this study, 152 female bats captured from the Manilkara zapota orchard of the University of Southern Mindanao were examined for their reproductive stages. Lactation of fruit bat species Ptenochirus jagori and Ptenochirus minor were positively correlated with the fruiting of M. zapota. While the lactation of Cynopterus brachyotis, Eonycteris spelaea and Rousettus amplexicaudatus were positively associated with the flowering of M. zapota. Together, thirty M. zapota trees were observed for their generative stage (fruiting or flowering) in 6 months. Based on the canonical correspondence analysis, only P. jagori was considered as the natural forager as its lactating stage coincides with the fruiting peaks and only C. brachyotis and E. spelaea were the potential pollinators since its lactating stage coincides with the flowering peaks ofM. zapota tree. The method in this study can be used to identify potential pollinators and foragers in other fruit trees. Keywords - agroforest, chiropterophily, frugivore, nocturnal, Sapotaceae Introduction pollination process is called chiropterophily. -

Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)

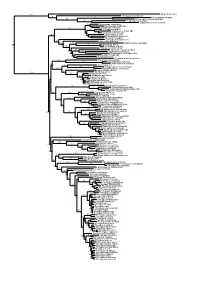

Chapter 6 Phylogenetic Relationships of Harpyionycterine Megabats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) NORBERTO P. GIANNINI1,2, FRANCISCA CUNHA ALMEIDA1,3, AND NANCY B. SIMMONS1 ABSTRACT After almost 70 years of stability following publication of Andersen’s (1912) monograph on the group, the systematics of megachiropteran bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) was thrown into flux with the advent of molecular phylogenetics in the 1980s—a state where it has remained ever since. One particularly problematic group has been the Austromalayan Harpyionycterinae, currently thought to include Dobsonia and Harpyionycteris, and probably also Aproteles.Inthis contribution we revisit the systematics of harpyionycterines. We examine historical hypotheses of relationships including the suggestion by O. Thomas (1896) that the rousettine Boneia bidens may be related to Harpyionycteris, and report the results of a series of phylogenetic analyses based on new as well as previously published sequence data from the genes RAG1, RAG2, vWF, c-mos, cytb, 12S, tVal, 16S,andND2. Despite a striking lack of morphological synapomorphies, results of our combined analyses indicate that Boneia groups with Aproteles, Dobsonia, and Harpyionycteris in a well-supported, expanded Harpyionycterinae. While monophyly of this group is well supported, topological changes within this clade across analyses of different data partitions indicate conflicting phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial partition. The position of the harpyionycterine clade within the megachiropteran tree remains somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, biogeographic patterns (vicariance-dispersal events) within Harpyionycterinae appear clear and can be directly linked to major biogeographic boundaries of the Austromalayan region. The new phylogeny of Harpionycterinae also provides a new framework for interpreting aspects of dental evolution in pteropodids (e.g., reduction in the incisor dentition) and allows prediction of roosting habits for Harpyionycteris, whose habits are unknown. -

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

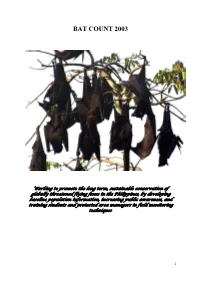

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

Conventional Wisdom on Roosting Behaviour of Australian

Conventional wisdom on roosting behaviour of Australian flying foxes - a critical review, and evaluation using new data Tamika Lunn1, Peggy Eby2, Remy Brooks1, Hamish McCallum1, Raina Plowright3, Maureen Kessler4, and Alison Peel1 1Griffith University 2University of New South Wales 3Montana State University 4Montana State University System April 12, 2021 Abstract 1. Fruit bats (Family: Pteropodidae) are animals of great ecological and economic importance, yet their populations are threatened by ongoing habitat loss and human persecution. A lack of ecological knowledge for the vast majority of Pteropodid bat species presents additional challenges for their conservation and management. 2. In Australia, populations of flying-fox species (Genus: Pteropus) are declining and management approaches are highly contentious. Australian flying-fox roosts are exposed to management regimes involving habitat modification, either through human-wildlife conflict management policies, or vegetation restoration programs. Details on the fine-scale roosting ecology of flying-foxes are not sufficiently known to provide evidence-based guidance for these regimes and the impact on flying-foxes of these habitat modifications is poorly understood. 3. We seek to identify and test commonly held understandings about the roosting ecology of Australian flying-foxes to inform practical recommendations and guide and refine management practices at flying-fox roosts. 4. We identify 31 statements relevant to understanding of flying-fox roosting structure, and synthesise these in the context of existing literature. We then contribute contemporary data on the fine-scale roosting structure of flying-fox species in south-eastern Queensland and north- eastern New South Wales, presenting a 13-month dataset from 2,522 spatially referenced roost trees across eight sites. -

NHBSS 042 1O Robinson Obs

Notes NAT. NAT. HIST. B 肌 L. SIAM Soc. 42: 117-120 , 1994 Observation Observation on the Wildlife Trade at the Daily Market in Chiang Kh an , Northeast Thailand In In a recent study into the wildlife trade between Lao PDR. and Thailand S即 KOSAMAT 組 A et al. (1 992) found 伽 tit was a major 伽 eat to wildlife resources in Lao. Th ey surveyed 15 locations along 白e 百凶 Lao border ,including Chiang Kh an. Only a single single visit was made to the market in Chiang Kh佃, on 8 April 1991 , and no wildlife products products were found. τbe border town of Chi 佃 g Kh an , Loei Pr ovince in northeast 百lailand is situated on the the banks of the Mekong river which sep 釘 ates Lao PD R. and 官 lailand. In Chiang Kh an there there is a small market held twice each day. Th e market ,situated in the centre of town , sells sells a wide r佃 ge of products from f記sh fruit ,vegetables , meat and dried fish to clothes and and household items. A moming market begins around 0300 h and continues until about 0800 h. The evening market st 紅白紙 1500 h and continues until about 1830 h. During During the period November 1992 to November 1993 visits were made to Chiang Kh佃 eve 凶ng market , to record the wildlife offered for sale. Only the presence of mam- mals ,reptiles and birds was recorded. Although frogs ,insects ,fish , crabs and 加 t eggs , as as well as meat 仕om domestic animals , were sold ,no record of this was made. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Social Structure of a Polygynous Tent-Making Bat, Cynopterus Sphinx (Megachiroptera)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Jay F. Storz Publications Papers in the Biological Sciences 6-2000 Social structure of a polygynous tent-making bat, Cynopterus sphinx (Megachiroptera) Jay F. Storz University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Hari Bhat National Institute of Virology, Pune, 411 001, India Thomas H. Kunz Boston University, 5 Cummington Street, Boston, MA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscistorz Part of the Genetics and Genomics Commons Storz, Jay F.; Bhat, Hari; and Kunz, Thomas H., "Social structure of a polygynous tent-making bat, Cynopterus sphinx (Megachiroptera)" (2000). Jay F. Storz Publications. 30. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscistorz/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jay F. Storz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Journal of Zoology 251:2 (June 2000), pp. 151–165; doi 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00600.x Copyright © 2000 The Zoological Society of London; published by Blackwell Publishing. Used by permission. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118535410/home Accepted for publication June 2, 1999. Social structure of a polygynous tent-making bat, Cynopterus sphinx (Megachiroptera) Jay F. Storz,1 Hari R. Bhat,2 and Thomas H. Kunz 1 1 Department of Biology, Boston University, 5 Cummington Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA 2 National Institute of Virology, Pune, 411 001, India; present address: 107 Awanti, OPP: Kamala Nehru Park, Erandawana, Pune, 411 004, India Abstract The social structure of an Old World tent-making bat Cynopterus sphinx (Megachiroptera), was investigated in western India. -

Taxonomy and Natural History of the Southeast Asian Fruit-Bat Genus Dyacopterus

Journal of Mammalogy, 88(2):302–318, 2007 TAXONOMY AND NATURAL HISTORY OF THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN FRUIT-BAT GENUS DYACOPTERUS KRISTOFER M. HELGEN,* DIETER KOCK,RAI KRISTIE SALVE C. GOMEZ,NINA R. INGLE, AND MARTUA H. SINAGA Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History (NHB 390, MRC 108), Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, USA (KMH) Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Senckenberganlage 25, Frankfurt, D-60325, Germany (DK) Philippine Eagle Foundation, VAL Learning Village, Ruby Street, Marfori Heights, Davao City, 8000, Philippines (RKSCG) Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA (NRI) Division of Mammals, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605, USA (NRI) Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Jl. Raya Cibinong Km 46, Cibinong 16911, Indonesia (MHS) The pteropodid genus Dyacopterus Andersen, 1912, comprises several medium-sized fruit-bat species endemic to forested areas of Sundaland and the Philippines. Specimens of Dyacopterus are sparsely represented in collections of world museums, which has hindered resolution of species limits within the genus. Based on our studies of most available museum material, we review the infrageneric taxonomy of Dyacopterus using craniometric and other comparisons. In the past, 2 species have been described—D. spadiceus (Thomas, 1890), described from Borneo and later recorded from the Malay Peninsula, and D. brooksi Thomas, 1920, described from Sumatra. These 2 nominal taxa are often recognized as species or conspecific subspecies representing these respective populations. Our examinations instead suggest that both previously described species of Dyacopterus co-occur on the Sunda Shelf—the smaller-skulled D. spadiceus in peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, and Borneo, and the larger-skulled D. -

Habitat Selection of Endangered and Endemic Large Flying-Foxes in Subic

Biological Conservation 126 (2005) 93–102 www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Habitat selection of endangered and endemic large Xying-foxes in Subic Bay, Philippines Tammy L. Mildenstein a,¤, Sam C. Stier a, C.E. Nuevo-Diego b, L. Scott Mills c a c/o US Peace Corps, Patio Madrigal Compound, 2775 Roxas Blvd., Pasay City, Metro Manila, Philippines b 9872 Isarog St. Umali Subdivision, Los Baños, Laguna 4031, Philippines c Wildlife Biology Program, School of Forestry, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812-0596, USA Received 6 June 2004 Available online 5 July 2005 Abstract Large Xying-foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to high levels of deforestation and hunting and eVectively little local conservation commitment. The forest at Subic Bay, Philippines, supports a rare, large colony of vulnerable Philippine giant fruit bats (Pteropus vampyrus lanensis) and endangered and endemic golden-crowned Xying-foxes (Acerodon jubatus). These large Xying-foxes are optimal for conservation focus, because in addition to being keystone, Xagship, and umbrella species, the bats are important to Subic Bay’s economy and its indigenous cultures. Habitat selection information stream- lines management’s eVorts to protect and conserve these popular but threatened animals. We used radio telemetry to describe the bats’ nighttime use of habitat on two ecological scales: vegetation and microhabitat. The fruit bats used the entire 14,000 ha study area, including all of Subic Bay Watershed Reserve, as well as neighboring forests just outside the protected area boundaries. Their recorded foraging locations ranged between 0.4 and 12 km from the roost. -

Galorio A. H. N., Nuneza O. M., 2014 Diet of Cave-Dwelling Bats In

ABAH BIOFLUX Animal Biology & Animal Husbandry International Journal of the Bioflux Society Diet of cave-dwelling bats in Bukidnon and Davao Oriental, Philippines Al H. N. Galorio, Olga M. Nuñeza Department of Biological Sciences, College of Science and Mathematics, Mindanao State University - Iligan Institute of Technology, Iligan City, Philippines. Corresponding author: O. M. Nuñeza, [email protected] Abstract. The Philippine archipelago has high species richness of bats, many of which are cave-dwellers. Information on the feeding behavior of these species is important toward their conservation. This study was conducted to determine the diet of 8 species of cave-dwelling bats from 13 cave sites in Mindanao, Philippines based on percentage occurrence of the diet items in the gut contents. Among the frugivorous species, Rousettus amplexicaudatus had the highest percentage occurrence of fruit bits (73.68 %) and fruit fibers (36.84 %) suggesting high fruit consumption. Some individuals of Cynopterus brachyotis were found to consume Ficus sp. seeds while a Ptenochirus jagori individual had an unidentified seed in the gut. Insect limbs were present in the diet of R. amplexicaudatus and P. jagori. Presence of insects in these fruit-eating bats implies that these bats might have consumed fruits along with the insects associated with the fruits. Among the insect-eating bats, digested insect parts, wings, limbs, and exoskeletons of Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Orthoptera, and Scotinophara sp. were observed in their gut. Fruit bits and fruit fibers observed in Hipposideros diadema, Miniopterus schreibersii and Taphozous melanopogon suggest that these bats consumed insects as well as fruits or fruits associated with certain insects. -

Bats of the Philippine Islands –A Review of Research Directions and Relevance to National- 2 Level Priorities and Targets 3 Krizler Cejuela

1 Bats of the Philippine Islands –a review of research directions and relevance to national- 2 level priorities and targets 3 Krizler Cejuela. Tanalgo & Alice Catherine Hughes 4 Landscape Ecology Group, Centre for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, 5 Chinese Academy of Sciences, Yunnan, P.R. China 6 7 Abstract 8 Effective science-based conservation priorities and policies are crucially important to 9 effectively maintain biodiversity into the future. For many threatened species and systems 10 insufficient information exists to generate priorities, or the mechanisms needed to effectively 11 conserve species into the future, and this is especially important in megadiversity countries like 12 the Philippines, threatened by rapid rates of development and with few overarching strategies 13 to maintain their biodiversity. Here, using a bibliographic approach to indicate research 14 strengths and priorities, we summarised scientific information on Philippine bats from 2000- 15 2017. We examine relationships between thematic areas and effort allocated for each species 16 bat guild, and conservation status. We found that an average of 7.9 studies was published 17 annually with the majority focused on diversity and community surveys. However, research 18 effort is not even between taxonomic groups, thematic areas or species, with disproportionate 19 effort focusing on ‘taxonomy and systematics’ and ‘ecology’. Species effort allocation between 20 threatened and less threatened species does not show a significant difference, though this may 21 be because generalist species are found in many studies, whereas rarer species have single 22 species studies devoted to them. A growing collaborative effort in bat conservation initiatives 23 in the Philippines has focused on the protection of many endemic and threatened species (e.g., 24 flying foxes) and their habitats.