Eonycteris Spelaea Dobson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

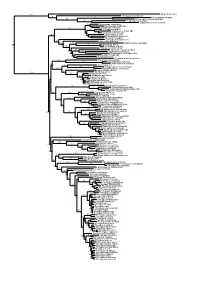

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

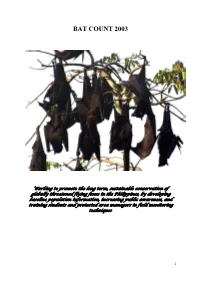

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

Conventional Wisdom on Roosting Behaviour of Australian

Conventional wisdom on roosting behaviour of Australian flying foxes - a critical review, and evaluation using new data Tamika Lunn1, Peggy Eby2, Remy Brooks1, Hamish McCallum1, Raina Plowright3, Maureen Kessler4, and Alison Peel1 1Griffith University 2University of New South Wales 3Montana State University 4Montana State University System April 12, 2021 Abstract 1. Fruit bats (Family: Pteropodidae) are animals of great ecological and economic importance, yet their populations are threatened by ongoing habitat loss and human persecution. A lack of ecological knowledge for the vast majority of Pteropodid bat species presents additional challenges for their conservation and management. 2. In Australia, populations of flying-fox species (Genus: Pteropus) are declining and management approaches are highly contentious. Australian flying-fox roosts are exposed to management regimes involving habitat modification, either through human-wildlife conflict management policies, or vegetation restoration programs. Details on the fine-scale roosting ecology of flying-foxes are not sufficiently known to provide evidence-based guidance for these regimes and the impact on flying-foxes of these habitat modifications is poorly understood. 3. We seek to identify and test commonly held understandings about the roosting ecology of Australian flying-foxes to inform practical recommendations and guide and refine management practices at flying-fox roosts. 4. We identify 31 statements relevant to understanding of flying-fox roosting structure, and synthesise these in the context of existing literature. We then contribute contemporary data on the fine-scale roosting structure of flying-fox species in south-eastern Queensland and north- eastern New South Wales, presenting a 13-month dataset from 2,522 spatially referenced roost trees across eight sites. -

NHBSS 042 1O Robinson Obs

Notes NAT. NAT. HIST. B 肌 L. SIAM Soc. 42: 117-120 , 1994 Observation Observation on the Wildlife Trade at the Daily Market in Chiang Kh an , Northeast Thailand In In a recent study into the wildlife trade between Lao PDR. and Thailand S即 KOSAMAT 組 A et al. (1 992) found 伽 tit was a major 伽 eat to wildlife resources in Lao. Th ey surveyed 15 locations along 白e 百凶 Lao border ,including Chiang Kh an. Only a single single visit was made to the market in Chiang Kh佃, on 8 April 1991 , and no wildlife products products were found. τbe border town of Chi 佃 g Kh an , Loei Pr ovince in northeast 百lailand is situated on the the banks of the Mekong river which sep 釘 ates Lao PD R. and 官 lailand. In Chiang Kh an there there is a small market held twice each day. Th e market ,situated in the centre of town , sells sells a wide r佃 ge of products from f記sh fruit ,vegetables , meat and dried fish to clothes and and household items. A moming market begins around 0300 h and continues until about 0800 h. The evening market st 紅白紙 1500 h and continues until about 1830 h. During During the period November 1992 to November 1993 visits were made to Chiang Kh佃 eve 凶ng market , to record the wildlife offered for sale. Only the presence of mam- mals ,reptiles and birds was recorded. Although frogs ,insects ,fish , crabs and 加 t eggs , as as well as meat 仕om domestic animals , were sold ,no record of this was made. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Tongued Fruit Bat Eonycteris Spelaea Dobson, 1873, Known from India

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 September 2016 | 8(11): 9371–9374 Note First record of Dobson’s Long- species of the genus Eonycteris tongued Fruit Bat Eonycteris spelaea Dobson, 1873, known from India. (Dobson, 1871) (Mammalia: Chiroptera: Dobson’s Long-tongued Fruit Pteropodidae) from Kerala, India Bat Eonycteris spelaea was initially ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) known only from Myanmar, ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) P.O. Nameer 1, R. Ashmi 2, Sachin K. Aravind 3 & Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, R. Sreehari 4 Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines OPEN ACCESS (Blanford 1891; Ellerman & 1,2,3,4 Centre for Wildlife Studies, College of Forestry, Kerala Agricultural Morrison-Scott 1951). In India University, Thrissur, Kerala 680656, India Eonycteris spelaea 2 Current address: Tranumparken 18, Brøndby Strand, Copenhagen was reported 2660, Denmark only in 1967 from the Kumaon Hills, now in Uttarakhand 4 Current address: Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese State (Bhat 1968). Subsequently, this species was also Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla, Yunnan 666303, China 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 ashmiramachandran@ reported from other Indian states and union territories gmail.com, 3 [email protected], 4 [email protected] such as Assam (Ghose & Bhattacharya 1974) Andaman & Nicobar Islands (Bhattacharya 1975), Karnataka (Bhat et al. 1980), Sikkim (Mistry, 1991), Nagaland (Sinha 1994), Meghalaya (Das et al. 1995), and Andhra Pradesh (Bates The fruit bats of the family Pteropodidae are & Harrison 1997). an ancient and diverse group of bats, distributed Materials and Methods: The study was conducted throughout the tropical regions of Africa, Asia and Indo- at the Parambikulam Tiger Reserve (PkTR), which is Australia (Hill & Smith 1984). -

(Pteropus Giganteus) in LAHORE in WILDLIFE and ECOLOGY D

ROOST CHARACTERISTICS, FOOD AND FEEDING HABITS OF THE INDIAN FLYING FOX (Pteropus giganteus) IN LAHORE BY TAYIBA LATIF GULRAIZ Regd. No. 2007-VA-508 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN THE PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN WILDLIFE AND ECOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE AND ECOLOGY FACULTY OF FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE UNIVERSITY OF VETERINARY AND ANIMAL SCIENCES LAHORE, PAKISTAN 2014 The Controller of Examinations, University of Veterinary & Animal Sciences, Lahore. We, the Supervisory Committee, certify that the contents and form of the thesis, submitted by Tayiba Latif Gulriaz, Registration No. 2007-VA-508 have been found satisfactory and recommend that it be processed for the evaluation by the External Examination (s) for award of the Degree. Chairman ___________________________ Dr. Arshad Javid Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Dr. Muhammad Mahmood-ul-hassan Member ____________________________ Dr. Khalid Mahmood Anjum Member ______________________________ Prof. Dr. Azhar Maqbool CONTENTS NO. TITLE PAGE 1. Dedication ii 2. Acknowledgements iii 3. List of Tables iv 4. List of Figures v CHAPTERS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. REVIEW OF LITERATURE 4 2.1 Order Chiroptera 10 2.1.1 Chiropteran status in Indian sub-continent 11 2.1.2 Representative Megachiroptera in Pakistan 11 2.2 Habitant of Pteropodidae 13 2.2.1 Roost of Pteropus 14 2.2.2 Roost observation of Pteropus giganteus (Indian flying fox) 15 2.3 Colonial ranking among Pteropus roost 17 2.3.1 Maternal colonies of Pteropus species 19 2.4 Feeding adaptions in frugivorous bats 20 2.4.1 Staple food of Pteropodids 21 2.5 Bats as pollinators and seed dispersers 23 2.5.1 Conflict with fruit growers 24 2.6 Bat guano 25 2.6.1 Importance of bat guano 27 2.7 Perspicacity 28 2.8 The major threats to the bats 29 2.8.1 Urbanization 30 2.8.2 Deforestation 31 2.9 Approbation 33 Statement of Problem 34 2.10 Literature cited 35 3.1 Roost characteristics and habitat preferences of Indian flying 53 3. -

Anthropogenic Impacts on Cave-Roosting Bats

Available online athttp://www.ssstj.sci.ssru.ac.th Suan Sunandha Science and Technology Journal ©2018 Faculty of Science and Technology, Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University __________________________________________________________________________________ Anthropogenic Impacts on Cave-roosting Bats: A Call for Conservation Policy Implementation in Bukidnon, Philippines Kim-Lee Bustillo Domingo, Dave Paladin Buenavista* Department of Biology, Central Mindanao University, Musuan, Bukidnon 8710, Philippines Corresponding author e-mail: *[email protected] Abstract Many caves in the Philippines are amongst the most popular natural ecotourism sites, even though most of them are poorly regulated and understudied. This study investigates the anthropogenic impacts of unsustainable eco- tourism and exploitation on cave-roosting bats in Sumalsag Cave, Bukidnon, Mindanao Island, Philippines. The species richness of the cave-roosting bat fauna was determined using the standard mist-netting method and capture-mark and release technique. The conservation status was assessed based on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. Ecological evaluation and assessment of the cave’s speleological characteristics and ecological condition was carried out using the Philippines’ standard cave assessment protocol. After completing 15 net-nights field sampling with a capture effort of 180 net/hours, results revealed a total of six (6) species of cave-roosting bats which belongs to three (3) families. Two Philippine endemic species, Ptenochirus jagori and Ptenochirus minor were documented including Miniopterus schreibersii, a species classified under near threatened category. Evidence of human activities were considered for identifying the indirect and direct threats on the bat fauna. Destroyed speleothems and speleogens, excavations, modifications of the cave’s features as well as graffiti in the cave walls were recorded. -

Interrogating Phylogenetic Discordance Resolves Deep Splits

Interrogating Phylogenetic Discordance Resolves Deep Splits in the Rapid Radiation of Old World Fruit Bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) Nicolas Nesi, Georgia Tsagkogeorga, Susan Tsang, Violaine Nicolas, Aude Lalis, Annette Scanlon, Silke Riesle-Sbarbaro, Sigit Wiantoro, Alan Hitch, Javier Juste, et al. To cite this version: Nicolas Nesi, Georgia Tsagkogeorga, Susan Tsang, Violaine Nicolas, Aude Lalis, et al.. Interrogat- ing Phylogenetic Discordance Resolves Deep Splits in the Rapid Radiation of Old World Fruit Bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae). Systematic Biology, Oxford University Press (OUP), 2021, 10.1093/sys- bio/syab013. hal-03167896 HAL Id: hal-03167896 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-03167896 Submitted on 12 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Interrogating Phylogenetic Discordance Resolves Deep Splits in the Rapid Radiation of Old World Fruit Bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sysbio/advance-article/doi/10.1093/sysbio/syab013/6161783 by Sorbonne Université user on 12 March 2021 NICOLAS NESI1, GEORGIA TSAGKOGEORGA1, SUSAN M. TSANG2,3, VIOLAINE NICOLAS4, AUDE LALIS4, ANNETTE T. SCANLON5, SILKE A. RIESLE- SBARBARO6,7†, SIGIT WIANTORO8, ALAN T. HITCH9, JAVIER JUSTE10, CORINNA A. PINZARI11, FRANK J. BONACCORSO12, CHRISTOPHER M. -

Citizen Science Confirms the Rarity of Fruit Bat Pollination of Baobab

diversity Article Citizen Science Confirms the Rarity of Fruit Bat Pollination of Baobab (Adansonia digitata) Flowers in Southern Africa Peter J. Taylor 1,* , Catherine Vise 1,2, Macy A. Krishnamoorthy 3, Tigga Kingston 3 and Sarah Venter 4 1 School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences, University of Venda, Private Bag X5050, Thohoyandou 0950, South Africa; [email protected] 2 Wallace Dale Farm 727MS, PO Box 52, Louis Trichardt, Limpopo 0920, South Africa 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA; [email protected] (M.A.K.); [email protected] (T.K.) 4 School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, WITS 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-15-962-9326 Received: 8 February 2020; Accepted: 12 March 2020; Published: 19 March 2020 Abstract: The iconic African baobab tree (Adansonia digitata) has “chiropterophilous” flowers that are adapted for pollination by fruit bats. Although bat pollination of baobabs has been documented in east and west Africa, it has not been confirmed in southern Africa where it has been suggested that hawk moths (Nephele comma) may also be involved in baobab pollination. We used a citizen science approach to monitor baobab tree and flower visitors from dusk till midnight at 23 individual baobab trees over 27 nights during the flowering seasons (November–December) of 2016 and 2017 in northern South Africa and southern Zimbabwe (about 1650 visitors). Insect visitors frequently visited baobab flowers, including hawk moths, but, with one exception in southeastern Zimbabwe, no fruit bats visited flowers. -

X Pounsin Et

Journal of Tropical Biology and Conservation 13: 101–118, 2016 ISSN 1823-3902 Research Article Brief Mist-netting and Update of New Record of Bats at Tumunong Hallu in Silam Coast Conservation Area (SCCA), Lahad Datu, Sabah, Malaysia. Grace Pounsin¹*, Simon Lagundi², Isham Azhar3 , Mohd. Tajuddin Abdullah4 1School of Marine and Environmental Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, 21030, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia. ²Silam Coast Conservation Area, P.O. Box 60282, 91100, Lahad Datu, Sabah. 3Faculty of Natural Science and Sustainability, University College Sabah Foundation, Jalan Sanzac, 88100, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia. 4Centre for Kenyir Ecosystems Research, Kenyir Research Institute, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, 21030, Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu, Malaysia. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract A bat survey was conducted at Tumunong Hallu in Silam Coast Conservation Area (SCCA), Lahad Datu, Sabahfollowing the Silam Scientific Expedition 2015 from 7th July until 5th August 2015. A total of nine bat species belonging to two families were captured at SCCA. Among the noteworthy species recorded from this survey were Rhinolophus sedulus and Pteropus vampyrus, which are listed as Near Threatened in the IUCN Red List. Keywords: Chiroptera, Sabah, Tumunong Hallu, Silam Coast Conservation Area (SCCA). Introduction Silam Coast Conservation Area (SCCA) is one of the conservation areas managed by Yayasan Sabah Group along with Danum Valley Conservation Area (DVCA), Maliau Basin Conservation Area (MBCA) and Imbak Canyon Conservation Area (ICCA). Initially, the area covered 580 hectares before it was expanded to 2,770 hectares in 2014 after its management was handed over to Yayasan Sabah Group in 1997. The SCCA is located in Darvel Bay, which is globally known as a region with marine-rich biodiversity and also a part of the Priority Conservation Area of the Sulu-Sulawesi Marine Eco-region. -

List of Taxa for Which MIL Has Images

LIST OF 27 ORDERS, 163 FAMILIES, 887 GENERA, AND 2064 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 JULY 2021 AFROSORICIDA (9 genera, 12 species) CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles 1. Amblysomus hottentotus - Hottentot Golden Mole 2. Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole 3. Eremitalpa granti - Grant’s Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus - Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale cf. longicaudata - Lesser Long-tailed Shrew Tenrec 4. Microgale cowani - Cowan’s Shrew Tenrec 5. Microgale mergulus - Web-footed Tenrec 6. Nesogale cf. talazaci - Talazac’s Shrew Tenrec 7. Nesogale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 8. Setifer setosus - Greater Hedgehog Tenrec 9. Tenrec ecaudatus - Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (127 genera, 308 species) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale 2. Eubalaena australis - Southern Right Whale 3. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale 4. Eubalaena japonica - North Pacific Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei – Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale 7. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 8. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE (54 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Common Impala 3. Aepyceros petersi - Black-faced Impala 4. Alcelaphus caama - Red Hartebeest 5. Alcelaphus cokii - Kongoni (Coke’s Hartebeest) 6. Alcelaphus lelwel - Lelwel Hartebeest 7. Alcelaphus swaynei - Swayne’s Hartebeest 8. Ammelaphus australis - Southern Lesser Kudu 9. Ammelaphus imberbis - Northern Lesser Kudu 10. Ammodorcas clarkei - Dibatag 11. Ammotragus lervia - Aoudad (Barbary Sheep) 12.