Bulletin of the GHI Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

![Explain Why Germans Were So Angry About the Treaty of Versailles [8] Advice](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6093/explain-why-germans-were-so-angry-about-the-treaty-of-versailles-8-advice-406093.webp)

Explain Why Germans Were So Angry About the Treaty of Versailles [8] Advice

Explain why Germans were so angry about the Treaty of Versailles [8] Advice AO1: Demonstrate knowledge and AO2: Explain why Germans were angry understanding of the period about the Treaty An [8] mark question on the Germany paper wants you to explain the cause of Band 1 (1 Band 2 (2 Band 3 (3 Band 1 (1 Band 2 (2-3 Band 3 (4-5 something – in this case, why ordinary German people were angry at the Treaty mark) marks) marks) mark) marks) marks) of Versailles. To answer this question, you need to know: I include I include I include I give very I partially I give a very very few some of the very little explain why detailed What Germany was like before WW1 details of Treaty and detailed explanation Germans and logical Details of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles the Treaty why information of why were angry explanation What kind of peace treaty Germany expected to get and why Germans about the Germans about the of why Germans were angry Treaty and were angry Treaty Germans Why the Treaty of Versailles was so bad for Germany were angry about it why about the were angry You aim to write at least 2 P.E.E.L. paragraphs (Point, Evidence, Explanation, Link). about it Germans Treaty about the were angry Treaty [8] marks means you should spend about 8 minutes on this question. about it S/A or P/A Teacher Mark and Comment: Use this space to plan your answer: /8 /8 Suggested Improvements: Include some / more details of the terms of the Treaty or how it affected German people Add / give more explanation of why Germans were angry about the Treaty Improve quality of explanation by using P.E.E.L. -

266900Wp0english0inclusive0e

INCLUSIVE EDUCATION: ACHIEVING EDUCATION FOR ALL BY INCLUDING THOSE WITH DISABILITIES AND SPECIAL EDUCATION NEEDS Public Disclosure Authorized SUSAN J. PETERS, PH.D.* PREPARED FOR THE DISABILITY GROUP THE WORLD BANK April 30, 2003 Public Disclosure Authorized The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this report are entirely those of the author and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, to members of its Board of Executive Directors, or to the countries they represent. The report has gone through an external peer review process, and the author thanks those individuals for their feedback. Public Disclosure Authorized *Susan J. Peters is an Associate Professor in the College of Education, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, USA. She has been an educator and disability scholar for the past 20 years and has published in various international journals. She is the co-author and editor of two books: Education and Disability in Cross-Cultural Perspective (NY: Garland Publishing. 1993) and Disability and Special Needs Education in an African Context (Harare: College Press. 2001). She may be contacted at [email protected] Public Disclosure Authorized TABLE OF CONTENTS INCLUSIVE EDUCAITON: ACHIEVING EDUCATION FOR ALL BY INCLUDING THOSE WITH DISABILITIES AND SPECIAL EDUCATION NEEDS Glossary of Terms Executive Summary 1 I. Introduction 9 Background II. Inclusive Education Practice: Lessons from the North 18 Background Best Practice in Canada and the United States Best Practice in Europe and other OECD Countries Special Issues: Accountability Special Issues: Parental Involvement Special Issues: Gender Summary III. Inclusive Education Practice: Lessons from the South 26 Introduction IE: The Experience of “Southern Hemisphere School System Inclusive Education Framework Challenges and Responses to IE in the South Barriers Gaps in the Literature Considerations for Future Study Zambia Honduras Vietnam India Summary IV. -

Walther Rathenau, Gustav Stresemann, Konrad Adenauer

Walter Rathenau, Gustav Stresemann, Konrad Adenauer, Willy Brandt Ansprache auf der Botschafterkonferenz anlässlich der Namensgebung der Konferenzräume des Auswärtigen Amtes Berlin, 6. September 2006 Von Gregor Schöllgen Es gilt das gesprochene Wort. Herr Minister, Exzellenzen, meine Damen und Herren: Ich danke für die ehrenvolle Einladung. Und ich danke für das Vertrauen, das Sie in mich setzen: Wenn ich das richtig sehe, trauen Sie mir zu, vier herausragende Vertreter der deut- schen Außenpolitik im 20. Jahrhundert in zwanzig Minuten zu würdigen. Angemessen, versteht sich. Natürlich wissen Sie so gut wie ich, dass wir es hier mit vier Schwergewichten zu tun haben. Sonst hätten Sie sich ja auch nicht für diese Namensgebungen entschieden. Biografische Kurzportraits im vier mal Fünfminuten-Takt scheiden also aus. Stattdessen will ich fragen: Was haben die Vier gemeinsam - was unterscheidet sie? 1 * Um bei letzteren, also bei den Unterschieden, zu beginnen – weniger als man denken mag. Zum Beispiel die Ausbildung. Drei hatten studiert. Walther Rathenau hatte sich für Physik und Chemie entschieden, bezeichnenderweise begleitet von einem Studium der Philosophie; Gustav Stresemann war Nationalökonom, Konrad Adenauer Jurist. Zwei von ihnen, Rathenau und Stresemann, waren zudem promoviert. Der vierte, Willy Brandt, war weder promoviert noch examiniert, hatte nicht einmal studiert: Flucht und Exil ließen das nicht zu. Einiges spricht dafür, dass Willy Brandt diesen weißen Fleck in seiner Biografie mit seiner exessiven schriftstellerischen Tätigkeit kompensiert hat. Gewiss, er war von Hause aus Jour- nalist, und vor allem in späten Jahren kamen handfeste kommerzielle Interessen hinzu. Aber sie allein erklären seine Produktivität nicht: Weit mehr als 3.500 Veröffentlichungen aller Art sind beispiellos, jedenfalls für einen zeitlebens aktiven Politiker. -

The Soviet-German Tank Academy at Kama

The Secret School of War: The Soviet-German Tank Academy at Kama THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ian Johnson Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Jennifer Siegel, Advisor Peter Mansoor David Hoffmann Copyright by Ian Ona Johnson 2012 Abstract This paper explores the period of military cooperation between the Weimar Period German Army (the Reichswehr), and the Soviet Union. Between 1922 and 1933, four facilities were built in Russia by the two governments, where a variety of training and technological exercises were conducted. These facilities were particularly focused on advances in chemical and biological weapons, airplanes and tanks. The most influential of the four facilities was the tank testing and training grounds (Panzertruppenschule in the German) built along the Kama River, near Kazan in North- Central Russia. Led by German instructors, the school’s curriculum was based around lectures, war games, and technological testing. Soviet and German students studied and worked side by side; German officers in fact often wore the Soviet uniform while at the school, to show solidarity with their fellow officers. Among the German alumni of the school were many of the most famous practitioners of mobile warfare during the Second World War, such as Guderian, Manstein, Kleist and Model. This system of education proved highly innovative. During seven years of operation, the school produced a number of extremely important technological and tactical innovations. Among the new technologies were a new tank chassis system, superior guns, and - perhaps most importantly- a radio that could function within a tank. -

The Rarity of Realpolitik the Rarity of Brian Rathbun Realpolitik What Bismarck’S Rationality Reveals About International Politics

The Rarity of Realpolitik The Rarity of Brian Rathbun Realpolitik What Bismarck’s Rationality Reveals about International Politics Realpolitik, the pur- suit of vital state interests in a dangerous world that constrains state behavior, is at the heart of realist theory. All realists assume that states act in such a man- ner or, at the very least, are highly incentivized to do so by the structure of the international system, whether it be its anarchic character or the presence of other similarly self-interested states. Often overlooked, however, is that Real- politik has important psychological preconditions. Classical realists note that Realpolitik presupposes rational thinking, which, they argue, should not be taken for granted. Some leaders act more rationally than others because they think more rationally than others. Hans Morgenthau, perhaps the most fa- mous classical realist of all, goes as far as to suggest that rationality, and there- fore Realpolitik, is the exception rather than the rule.1 Realpolitik is rare, which is why classical realists devote as much attention to prescribing as they do to explaining foreign policy. Is Realpolitik actually rare empirically, and if so, what are the implications for scholars’ and practitioners’ understanding of foreign policy and the nature of international relations more generally? The necessity of a particular psy- chology for Realpolitik, one based on rational thinking, has never been ex- plicitly tested. Realists such as Morgenthau typically rely on sweeping and unveriªed assumptions, and the relative frequency of realist leaders is difªcult to establish empirically. In this article, I show that research in cognitive psychology provides a strong foundation for the classical realist claim that rationality is a demanding cogni- tive standard that few leaders meet. -

Walter Laqueur: the Last Days of Europe Study Guide

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Helms School of Government 2007 Walter Laqueur: The Last Days of Europe Study Guide Steven Alan Samson Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Samson, Steven Alan, "Walter Laqueur: The Last Days of Europe Study Guide" (2007). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 132. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs/132 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Helms School of Government at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WALTER LAQUEUR: THE LAST DAYS OF EUROPE STUDY GUIDE, 2007 Steven Alan Samson INTRODUCTION Study Questions 1. A Very Brief Tour Through the Future of Europe How have the sights, sounds, and smells of London, Paris, and Berlin changed since 1977? How did immigration to those cities differ one hundred years compared with today? What are the typical characteristics of the immigrants of 2006? 2. The Last Days of Old Europe What is “Old Europe?” What is the role of tourism in the European economy? What accounted for the author’s optimism in the 1970s? What were some of the danger signs in the 1970s? What did leading demographers show? What were some of Russia’s problems in the 1980s? How did the new immigrants differ from the guest workers of the 1950s? How did the European vision differ from the American dream? What accounted for the rosy picture painted of Europe by Tony Judt, Mark Leonard, and Charles Kupchan? What was the general consensus of EU’s 2000 meeting in Lisbon? Review danger signs in the 1970s new immigrants resistance to assimilation European vision Tony Judt CHAPTER ONE: EUROPE SHRINKING Study Questions 1. -

Speech by Federal President Joachim Gauck to Introduce a Panel Discussion at the Nobel Institute on 11 June 2014 in Oslo

Translation of advance text The speech on the internet: www.bundespraesident.de Berlin, 11 June 2014 Page 1 of 4 Speech by Federal President Joachim Gauck to introduce a panel discussion at the Nobel Institute on 11 June 2014 in Oslo At the end of 1969 there were rumours going around in Germany that Norway had had quite an unexpected Christmas present that year. On Christmas Eve, large oil and gas deposits had been discovered off the coast of Norway. Since that day, we continental Europeans have got to know, and value, a new side to the Norwegians. Not only did we get to know you as a reliable energy supplier and one of the most affluent countries in the world. We now also began to value Norway for the responsible manner in which it dealt with its newly won wealth. The revenues from the oil industry – the majority at least – were and are saved year after year and invested in the future, a future in which oil reserves one day will no longer be so abundant. Moreover, Norway with its new riches has by no means become self-satisfied, or “self-sufficient”. Isolationism has not become a Norwegian characteristic. The Norwegians have always cast their sights out onto the world. It is remarkable to note how many of the important explorers and pioneers of modern history came from Norway. Their names have a certain ring to them in Germany too: Roald Amundsen, Thor Heyerdahl and Fridtjof Nansen. And the fact that for more than one hundred years now, the most important prize in the world – the Nobel Peace Prize – is awarded here in Oslo is testament to Norway’s keen interest in global affairs. -

Change in Germany Between …? (6)

45 min exam 5 questions 1) Describe the … (5 marks) Germany 2) How far did …change in Germany between …? (6) 3) Arrange the …in order of their significance in … 1919- Germany after the ... Explain your choices. (9) 4) Explain why …different for 1991 … Germans after ... (8) 5) How important was …in Hitler`s …between …? (12) 1 Pages 3- 11 Pages 13- 20 Pages 21- 28 Pages 29- 37 Pages 38- 46 Pages 47- 54 Pages 55- 62 2 KEYWORDS Reparations Money which Germany Key Qu- 1 had to pay the Allies from How successful were the 1921 League of Nations Organisation to keep the Weimar government in peace in the world Weimar constitution The new democratic dealing with Germany’s government of Germany problems between 1919- Spartacist Uprising Communist revolt against 1933? the Weimar government Kapp putsch Right-wing revolt against the Weimar government You need to know about: Freikorps Ex-servicemen from WW1 • Impact of WW1 p4 Gustav Stresemann Chancellor of Germany • Terms of the Treaty of Versailles p4 1923 • The Weimar Republic p5 Foreign minister 1923-29 • Opposition to the Republic p6 Dawes Plan 1924- $800m gold marks • Economic/political/ foreign reform lent to Germany under Stresemann p7-8 Hyperinflation When the prices of goods rise significantly above wages 3 KEY QUESTION 1- How successful were the Weimar government in dealing with Germany’s problems between 1919-1933? Impact of WW1 on Treaty of Versailles (28 June 1919) War Guilt clause 231: Germany accepted blame for ‘causing all the loss Germany and damage’ of the war. • Naval mutiny at Kiel and violent protests over Army: 100,000/no submarines/no aeroplanes/6 battleships/No military Germany led to Kaiser’s abdication. -

The War to End War CERI

THE LAW OF THE WORLD OONA A. HATHAWAY & SCOTT J. SHAPIRO INTRODUCTION If you were to ask at what moment the world as we know it was set into motion, few, if any, would point to August 27, 1928. On that day, the representatives of the great powers of the world packed into the ornate, chandelier-filled room of the Salle de l’Horloge deep within the Quai d’Orsay, which housed the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It was a room heavy with history— the beleaguered Versailles Treaty had been concluded in the same room almost a decade earlier.1 The crowded space was sweltering from six large movie lights set up to help capture the momentous event on film. Sitting in a horseshoe, the representatives of the fifteen assembled states faced a small table at the center of the room, on which the treaty lay. At the center sat Aristide Briand, the aristocratic Frenchman who had first proposed a treaty to renounce war.2 Briand did not look the part of the French statesman. Not tall or in any way striking, his face was furrowed and partly obscured by a long drooping mustache.3 It was said that he often gave the impression of being bored.4 Yet Briand was no jaded diplomat. Both as Prime Minister and as Foreign Minister, he had worked tirelessly to protect France with a web of protective treaties. Often credited with formulating the original proposal for a new economic union of Europe,5 he had just two years earlier received the Nobel Peace Prize for his part in negotiating the Locarno Treaties, which aimed to bring a close to disputes that lingered from the Great War. -

Aristide Briand: Defending the Republic Through Economic Appeasement

Robert Boyce, "Aristide Briand : defending the Republic through economic appeasement", Histoire@Politique. Politique, culture, société, n° 16, janvier-avril 2012, www.histoire-politique.fr Aristide Briand: defending the Republic through economic appeasement Robert Boyce Aristide Briand occupied a major place in the politics of the Third Republic. For nearly twenty years he was a prominent political activist and journalist. Then, upon entering parliament he was eleven times président du Conseil and a minister on no less than twenty-five occasions, participating in government almost continuously from 1906 to 1917, in 1921-1922 and again from 1925 to 1932. Never during his thirty- year parliamentary career, however, did he take responsibility for a ministry of commerce, industry or finance or participate in debates on fiscal policy or budget reform. It might be said, indeed, that of all the leading politicians of the Third Republic he was one of the least interested in economic issues. Since he repeatedly altered his political posture before and after entering parliament, his approach to economics is difficult to define. Nevertheless it is possible to identify certain underlying beliefs that informed his political behaviour and shaped his economic views. In order to analyse these beliefs, their evolution and their instrumentalisation, the present paper will treat his public life in three stages: the long period before entering parliament, the period from 1902 to the war when he established his reputation as a progressive political leader, and the period from 1914 to 1932 when he became France's leading statesman. As will be seen, changing circumstances led him repeatedly to alter his posture towards economic choices, but in the second stage he became associated with potentially important domestic social and economic reforms, and in the third stage with potentially important international economic reforms. -

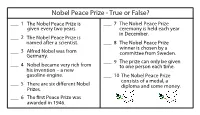

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money.