Lhasa: Urbanising China in the Frontier Regions ⁎ Tingting Chena,B, Wei Langa,B, , Edwin Chanc, Conrad H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Q19 Earnings Call Presentation January 29, 2020 Forward Looking Statements

4Q19 Earnings Call Presentation January 29, 2020 Forward Looking Statements This presentation contains forward-looking statements made pursuant to the Safe Harbor Provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Forward-looking statements involve a number of risks, uncertainties or other factors beyond the company’s control, which may cause material differences in actual results, performance or other expectations. These factors include, but are not limited to, general economic conditions, disruptions or reductions in travel, as well as in our operations, due to natural or man-made disasters, pandemics, epidemics, or outbreaks of infectious or contagious diseases such as the coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China, new development, construction and ventures, government regulation, risks relating to our gaming licenses and subconcession, fluctuations in currency exchange rates and interest rates, substantial leverage and debt service, gaming promoters, competition, tax law changes, infrastructure in Macao, political instability, civil unrest, terrorist acts or war, legalization of gaming, insurance, our subsidiaries’ ability to make distribution payments to us, and other factors detailed in the reports filed by Las Vegas Sands with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward- looking statements, which speak only as of the date thereof. Las Vegas Sands assumes no obligation to update such information. Within this presentation, the company may make reference -

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Low Carbon Development Roadmap for Jilin City Jilin for Roadmap Development Carbon Low Roadmap for Jilin City

Low Carbon Development Low Carbon Development Roadmap for Jilin City Roadmap for Jilin City Chatham House, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Energy Research Institute, Jilin University, E3G March 2010 Chatham House, 10 St James Square, London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0)20 7957 5700 E: [email protected] F: +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration Number: 208223 Low Carbon Development Roadmap for Jilin City Chatham House, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Energy Research Institute, Jilin University, E3G March 2010 © Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2010 Chatham House (the Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinion of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London, SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: +44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978 1 86203 230 9 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Cover image: factory on the Songhua River, Jilin. Reproduced with kind permission from original photo, © Christian Als, -

English/ and New York City—8.538 Million in 2016; 789 Km

OVERVIEW Public Disclosure Authorized CHONGQING Public Disclosure Authorized 2 35 Public Disclosure Authorized SPATIAL AND ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION FOR A GLOBAL CITY Public Disclosure Authorized Photo: onlyyouqj. Photo: © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, inter- pretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judg- ment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. Citation Please cite the report as follows: World Bank. 2019. Chongqing 2035: Spatial and Economic Transfor- mation for a Global City. Overview. Washington, DC: World Bank. -

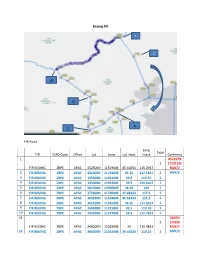

Shanghai FIR

Beijing FIR 1 2 19 15 8 11 FIR Point Long Type FIR ICAO Code Office Lat Long Lat Input Input Comment 1 452317N 1 1152115E FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 452500N 1151900E 45.40054 115.2947 RAN/2 2 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 431500N 1173100E 43.25 117.5167 1 RAN/2 3 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 395400N 1192100E 39.9 119.35 1 4 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 393000N 1195200E 39.5 119.8667 1 5 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 381500N 1200000E 38.25 120 1 6 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 372900N 1173000E 37.48333 117.5 1 7 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 363200N 1151800E 36.53333 115.3 1 8 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 362100N 1145500E 36.35 114.9167 1 9 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 360600N 1142100E 36.1 114.35 1 10 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 345400N 1124700E 34.9 112.7833 1 11 3405N 1 11029E FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 340000N 1102900E 34 110.4833 RAN/2 12 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 343200N 1101500E 34.53333 110.25 1 RAN/2 13 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 353200N 1101800E 35.53333 110.3 1 14 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 372800N 1104400E 37.46667 110.7333 1 15 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 382200N 1103600E 38.36666 110.6 1 16 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 384400N 1094100E 38.73333 109.6833 1 17 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 402000N 1070100E 40.33333 107.0167 1 18 FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 404300N 1055500E 40.71667 105.9167 1 19 414451N 1 1051345E FIR BEIJING ZBPE APAC 414400N 1051300E 41.74361 105.218 RAN/2 Along political boundary to (1) Note: 1. -

Bangladesh Chittagong China Hong Kong Shenzhen

Japan Tokyo 14 Dalian Seoul 15 Yokohama 17 South 13 Tianjin 8 16 Korea 12 Osaka-wan 10 Inch'on Kobe 7 6 9 Beijing Qingdao Busan Australia Australia 34 Brisbane 34 Brisbane Australia Australia 3 Shanghai Australia Brisbane 34 34 Brisbane 34 Brisbane China Taipei Australia Brisbane 29 34 New Delhi 21 Australia Taiwan Brisbane 5 Kao-hsiung Sydney 34 Guangzhou 32 Sydney 11 Perth 32 Hong Kong 36 Adelaide 2 Perth Bangladesh 36 35 Adelaide 4 35 Shenzhen Sydney Sydney Chittagong Sydney 32 32 Nagpur 23 Perth Perth Adelaide 32 18 Perth 36 36 Adelaide Mumbai (Bombay) 20 Philippines 36 Adelaide 35 35 Manila 27 Melbourne35 India 33 Melbourne 33 Sydney 32 Perth Thailand 36 Adelaide Sydney Auckland 35 Melbourne 32 Melbourne Vietnam Perth Melbourne 33 33 37 Auckland Bangkok 30 36 Adelaide33 37 Bangalore 22 19 Chennai (Madras) 35 31 Ho Chi Minh City Auckland Auckland Auckland 37 37 Melbourne New Zealand 37 33 New Zealand Melbourne Colombo 28 Sri Lanka Main Transport Terminals Trade(import-export) value Population (million people) 33 Malaysia Connections (billion US dollars) in 2007 AucklandNew Zealand 37 New Zealand Kuala Lumpur New Zealand Road Asia Highway >1000 0 - 2 Auckland 25 Network 37 26 Port of Tanjung 1 Indonesia International Airport 500 - 1000 2 - 5 Pelepas Singapore River New Zealand Sea Harbour 100 - 500 5 - 10 New Zealand River Harbour <100 0 245 490 Miles > 10 Free Economic Zone Jakarta 24 0 245 490 KM 1. Singapore 2. Hong Kong 3. Shanghai 4. Shenzhen 5. Kaohsiung 6. Busan 7. Beijing 8. Dalian Singapore is the world’s biggest container port with yearly throughput Hong Kong is a hub port serving the South Asian Pacific region and Shanghai is the power house for the economic growth of China. -

China - Peoples Republic Of

GAIN Report – CH9621 Page 1 of 25 THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 11/24/2009 GAIN Report Number: CH9621 China - Peoples Republic of Post: Guangzhou Zhuhai, South China’s city of romance . and more Report Categories: Market Development Reports Approved By: Joani Dong, Director Prepared By: May Liu Report Highlights: Zhuhai is touted as a romantic city because of its seaside beauty. But the place is more than just looks and proximity to Macau and Hong Kong. It’s one of China’s five Special Economic Zones and transportation and logistic hubs. It’s where the Aviation and Aerospace Exhibition is held and last year exhibited the Shenzhou 7 orbital module, famous for the first Chinese space walk. What’s more, Zhuhai is a market for U.S. agric ultural products in the retail sector and has links in the American swine sector. Its growth in the retail, restaurant and tourism sectors point to niche opportunities for U.S. agricultural products. This tiny, yet mighty city of 1.4 million is open for business. UNCLASSIFIED USDA Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN Report – CH9621 Page 2 of 25 Includes PSD Changes: No Includes Trade Matrix: No Annual Report Guangzhou ATO [CH3] [CH] Table of Content UNCLASSIFIED USDA Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN Report – CH9621 Page 3 of 25 I. Zhuhai Overview Zhuhai is known as a romantic city, clean and attractive, young and energetic. It is a relaxing place with rich natural resources; a population mixed with Macau, Hong Kong and expat transplants; and free trade zone open policy favorable for the younger generation and trade businessmen. -

A Tale of Five Cities: the China Residential Energy Consumption Survey

A Tale of Five Cities: The China Residential Energy Consumption Survey Debbie Brockett, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory David Fridley, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Jieming Lin, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Jiang Lin, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory ABSTRACT Consumption of electricity in the residential sector in China has risen faster than all other energy forms in China over the last 20 years, driven in part by the enormous increase in household appliance ownership, but few details are known about the characteristics of overall household energy use, particularly in the wake of the dramatic changes in the last two dec- ades. Despite the growing importance of this sector to the evolution of future energy con- sumption patterns, few data exist about the nature and type of urban household energy con- sumption. This paper summarizes the initial results of a first-ever 5-city, 251-household comprehensive survey of Chinese household energy use, taken in the cities of Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Yixing, and Shenyang. Focus in this paper is on analysis of the major electricity consuming products in households, but summaries of the findings on housing characteristics, space heating, air conditioning, hot water supply and use, indoor lighting, cooking, refrigeration, other appliances, house insulation, energy consumption in winter and summer months, energy prices, and household demographic information are also included. The findings support the current policy to emphasize development of minimum efficiency standards for household equipment, as energy consumption from these sources are a signifi- cant portion of the household energy budget. Background of China RECS In 1980, fully 90% of household energy in China derived from the direct burning of coal. -

Urbanization Effect on Precipitation Over the Pearl River Delta Based on CMORPH Data

+ MODEL Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Advances in Climate Change Research xx (2015) 1e7 www.keaipublishing.com/en/journals/accr/ Urbanization effect on precipitation over the Pearl River Delta based on CMORPH data CHEN Shenga,*, LI Wei-Biaoa, DU Yao-Dongb, MAO Cheng-Yanc, ZHANG Land a Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China b Guangdong Provincal Meteorological Service, Guangzhou 511430, China c Jiangshan Meteorological Bureau, Quzhou 324100, China d Guangzhou Meteorological Information Network Center, Guangzhou 511430, China Received 7 March 2015; revised 31 May 2015; accepted 25 August 2015 Abstract Based on the satellite data from the Climate Prediction Center morphing (CMORPH) at very high spatial and temporal resolution, the effects of urbanization on precipitation were assessed over the Pearl River Delta (PRD) metropolitan regions of China. CMORPH data has an accurate estimate of the precipitation features over the PRD. Compared to the surrounding rural areas, the PRD urban areas experience fewer and shorter precipitation events with a lower precipitation frequency (ratio of rainy hours, about 3 days per year less); however, short-duration heavy rain events play a more significant role over the PRD urban areas. Afternoon precipitation is much more pronounced over the PRD urban areas than the surrounding rural areas, which is probably because of the increase in short-duration heavy rain over urban areas. Keywords: CMORPH; Urbanization effects; Pearl River Delta 1. Introduction changes in the weather, local weather, and climate. A well- recognized phenomenon of the urban climate is the urban heat With rapid economic growth, China is undergoing rapid ur- island, in which there is a temperature contrast between a city banization. -

CMA CGM INTERMODAL CHINA Hubei Hunan Chongqing Sichuan

CHINA INTERMODAL HUBEI, HUNAN, CHONGQING AND SICHUAN One-stop solution for all your needs on land and at sea Hubei, Hunan, Chongqing and Sichuan provinces Nanjing Nanjing SICHUAN HUBEI Y a CHONGQING n Shanghai g Wuhan t z Chengdu Yichang Huangshi e Wanzhou r Fuling HUBEI i v Jingzhou e Chongqing r Jiujiang Ningbo Luzhou SICHUAN Yibin Yueyang Changde Nanchang Y Changsha Shangrao Yingtan HUNAN Xinyu a n CHONGQING Shanghai g Wuhan Shekou t Chengdu Yantian z Yichang Huangshi e Wanzhou r Fuling i v Jingzhou e Chongqing r Jiujiang Ningbo Luzhou Yibin Yueyang Changde Nanchang Changsha Shangrao Yingtan • HUNAN JIANGXI Ganzhou • CMA CGM Group Strengths • Full coverage of all destinations in provinces of Central & North China Xiamen Nansha • Reliable and rate competitive inland Shekou connection services by barge and Yantian rail, also with high frequency and Qinzhou short transit time • Characteristics rail service from Legend Chongqing and Changsha via Barge South China Rail Contacts • Possible to move over dimension cargo GU Sarah J • Customized solutions for projects [email protected] and special cargo Eileen KHANG • Possible to perform inland for Reefer shipment [email protected] 01-April-2021 CHINA INTERMODAL HUBEI, HUNAN, CHONGQING AND SICHUAN One-stop solution for all your needs on land and at sea SAILING FREQUENCY TRANSIT TIME PER WEEK in days CAPACITY IN PROVINCE ORIGIN POL MODE TEUS / SAILING OUTBOUND INBOUND OUTBOUND INBOUND WUHAN 6 7 8 7 JINGZHOU (SHASHI) 2 2 11 11-15 HUBEI 100-500 YICHANG 2 2 12 12-16 SHANGHAI BARGE HUANGSHI -

The People's Liberation Army's 37 Academic Institutions the People's

The People’s Liberation Army’s 37 Academic Institutions Kenneth Allen • Mingzhi Chen Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN: 9798635621417 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 Design by Heisey-Grove Design All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI Twitter: https://twitter.com/CASI_Research | @CASI_Research Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal, academic, or governmental use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete however, it is requested that reproductions credit the author and China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI). -

Food Production in Chongqing, China: Opportunities and Challenges

Middle States Geographer, 2016, 49: 55-62 FOOD PRODUCTION IN CHONGQING, CHINA: OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES M. Rock*, S. Engel-Di Mauro*, S. Chen, M. Iachetta, A. Mabey, K. McGill, J. Zhao Department of Geography, State University of New York at New Paltz 1 Hawk Drive, New Paltz, NY 12561 ABSTRACT: Urban food production (UFP) has been the subject of much interest, especially in light of worldwide urbanization trends. There have been many place-specific studies and overviews about UFP, but very little in China. Studies investigating enabling and constraining conditions and people’s motivations for UFP have also largely omitted China and they have entirely missed one of the fastest growing cities in the world, Chongqing. Research was carried out in several districts of Chongqing to assess the social composition of urban farmers and the conditions they face, as well as find out their reasons for farming in the city. Methods included transect walks, semi-structured interviews, crop inventory, and soil field analysis. Thirty interviews were carried out involving 37 participants, and crop and soil descriptions were completed at 28 and 15 sites, respectively. Results indicate that a majority of urban food producers are women and people older than 30 years. Most are not city natives and little more than half have had prior farming experience. They grow food often on thin soils in marginal spaces, usually having precarious land access contingent on business or government decisions that can lead to eviction or field destruction. Nevertheless, farmers grow a diversity of crops and sometimes raise other animals. Most farming is for subsistence and/or recreational and social networking possibilities afforded by UFP.