Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Colorado Concours Judging Results

2014 Colorado Concours Judging Results Registration Year Make Model Color Comments Number BEST OF SHOW CONCOURS D'ELEGANCE 1503 1955 Lancia Aurelia Spider Grigio One of 181 produced, this example was the 8th made and second oldest remaining today (the oldest being serial #1001 - the prototype). Freshly restored by owner Stephen Bell, this complete nut and bolt restoration took place in under a year and resulted in what is believed to be the most accurately restored example in existence today. Only 68 Aurelia Spiders are known to still exist. BEST OF SHOW CONCOURS D'SPORT 1968 McLaren M6B McLaren Orange Customer version of the M6A driven by Bruce McLaren in Can-Am. PEOPLE'S CHOICE 1828 1976 Porsche 930 Turbo Silver First Turbo Carrera built for the U.S. market. 1 of 2 turbos built April/May 1975. They were used for homologation purpose in U.S. This car is number 011. There were 4 turbo preproduction cars built for the U.S.: #011, #012, #013 and #014. Only #011 and #014 are left. No options were installed. Bought in November 1978 and I am the second owner. Engine is # 21and is original and unrestored - just general maintenance. On the Cover of Road and Track. The first 930 Turbo Carrera that started the rage of Turbos in America. CONCOURS JUDGING CLASSES Judged by the Colorado Concours judging teams - Head Judge Jerry Medina. NOVICE 1st Place 505 1967 Chevrolet Corvette Marboro Maroon Original numbers matching motor, transmission, and rear. Options include 427CI / 390HP motor, power steering, power brakes, four speed close ratio transmission, tinted windows, AM/FM radio, positraction rear, off road exhaust, white side wall tires. -

Exhaust Notes

Exhaust Notes Newsletter of the St Louis Triumph Owners Association Www.SLTOA.org Vol 15, Issue 12, December 2013 See page 6 In Memoriam Thanksgiving is a special season for all Americans. It gives us a time to count our Kjell Qvale blessings and to consider all the things we have to be thankful for. No matter what 1919-2013 View From Behind the Steering our economic, religious, or ethnic back- Wheel See pg 7 ground, the one thing that will come to the By Creig Houghtaling (Continued on page 7) 1 Calendar 6 Dec 2013—Annual SLTOA Christmas across from Gravois Bluffs in Fenton at 6 PM. Info at Party, Missouri Athletic Club-West, 1777 Des www.stlmgclub.com/events-calendar. Peres Rd, StL. See pg. 3. 11 Jan 2014—MGCStL Holiday Party, at Sqwire’s in La- 21 Jan 2014 – SLTOA monthly meeting fayette Square, 1415 S 18th St, St Louis. Cash bar at 5:30 PM, dinner at 6:30 PM, cost $15 per person (club 9 Feb 2014 – SLTOA Polar Bear Run. Annual all- subsidized), reservations must be made by Monday 6 weather kick-off driving event for the season, 16 January. Details including menu at February will serve as the backup date in the event www.stlouismgclub.com/events-calendar/. of really bad weather. Event route in planning, end 11 Jan 2014—Jaguar Association of Greater St Louis point at El Casa Grande del Moore (ie, Stephen y Annual Dinner and Awards Gala, at the Deer Creek Maria Moore’s), 5215 Mirasol Manor Way, Eureka Club, 9861 Deer Creek Hill, St Louis. -

The Jensen Interceptor: Chrysler-Powered British Luxury

The Jensen Interceptor: Chrysler- Powered British Luxury Allan and Richard Jensen's auto business was started before World War II, which interrupted production until 1950, when their first Interceptor was made. At the time, they made Austin bodies under contract, and the first Interceptor resembled an Austin A40 (the Jensens built bodies for a string of cars that included the Volvo P1800, Sunbeam Tiger, and Austin-Healey.) The first Interceptor used a 4 liter Austin in-line six, and was produced in small numbers for over a decade. Jensen also used Nash Twin-Ignition Eight engines for a time, and the 1962 C-V8 used a Chrysler 361 B-block engine. A number of these early Jensens made their way to the US before and after World War II. The next version kept the basic C-V8 chassis, but changed styling. Initially, an in-house convertible design was planned, but chief engineer Kevin Beattie argued for an Italian flavor. Proposals were taken from different design houses, with Carozzeria Touring winning out with a fastback coupe incorporating a rounded tail, but that house was unable to finalize the design. Vignale, instead, provided prototype and initial production bodies, rendered in steel, on CV-8 chassis sent to them by Jensen. Turnaround was quick - about four months - so the new Interceptors could be shown in London in October 1966. Jensen later used the jigs and tools, which were sent by Vignale to the West Bromwich factory. The body had two doors, a low beltline, and fishbowl rear glass in a handsome 2+2 design. -

The Significance of the Automobile in 20Th C. American Short Fiction

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2021 The Significance of the Automobile in 20th .C American Short Fiction Megan M. Flanery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, American Material Culture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Flanery, Megan M., "The Significance of the Automobile in 20th .C American Short Fiction" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2220. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/2220 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE AUTOMOBILE IN 20TH C. AMERICAN SHORT FICTION by MEGAN M. FLANERY ABSTRACT Midcentury American life featured a post-war economy that established a middle class in which disposable income and time for leisure were commonplace. In this socio-economic environment, consumerism flourished, ushering in the Golden Age of the automobile: from 1950 to 1960, Americans spent more time in their automobiles than ever before, and, by the end of the decade, the number of cars on the road had more than doubled. While much critical attention has been given to the role of the automobile in American novels, less has been given to its role in American short stories. -

Elizabeth Treadway

AMERICAN PUBLIC WORKS ASSOCIATION • SEPTEMBER 2012 • www.apwa.net Elizabeth Treadway takes the helm of APWA The All-New APWA Members’ Library More than 350 recorded Public Works Education Sessions Hundreds of articles, publications, videos, and more All at your fingertips, 24/7/365 www.apwa.net/memberslibrary September 2012 Vol. 79, No. 9 The APWA Reporter, the official magazine of the American Public Works Association, covers all facets of public works for APWA members including industry news, legislative actions, management issues and emerging technologies. FLEET SERVICES ISSUE INSIDE APWA 2 President’s Message 8 Technical Committee News 9 Recognize Your Leaders 10 The mentors of the APWA Donald C. Stone Center 12 Celebrating National Public Works Week 2012 with Southern Charm 16 City of San Antonio Disability Access Office 18 Employee Recognition 20 Fleet Services Committee announces new replacement planning publication 30 22 CPFP Campbell named Fleet Manager of the Year COLUMNS 6 Washington Insight 24 The Great 8 28 Global Solutions in Public Works 58 Ask Ann FEATURES 34 34 City of Ames, Iowa: Police cars replaced by need, not by time or miles 38 Road map to fleet success 42 How to reach out to the media 44 Fleet consolidation 48 Purchasing and installing publicly-accessible electric vehicle charging stations 52 Tool policies for employees 54 Six purchasing tips for fleet professionals 56 Trucking USA WORKZONE 38 56 WorkZone: Your Connection to Public Works Careers MARKETPLACE 60 Products in the News 65 Professional Directory CALENDARS 5 Education Calendar 68 World of Public Works Calendar 68 49 Index of Advertisers September 2012 APWA Reporter 1 Our profession has stepped up Elizabeth Treadway, PWLF APWA President Editor’s Note: As has become tradition, 2009-11), and most recently co-chaired each new APWA President is interviewed the Certification and Professional by the APWA Reporter at the beginning Development Group. -

The Dealership of Tomorrow 2.0: America’S Car Dealers Prepare for Change

The Dealership of Tomorrow 2.0: America’s Car Dealers Prepare for Change February 2020 An independent study by Glenn Mercer Prepared for the National Automobile Dealers Association The Dealership of Tomorrow 2.0 America’s Car Dealers Prepare for Change by Glenn Mercer Introduction This report is a sequel to the original Dealership of Tomorrow: 2025 (DOT) report, issued by NADA in January 2017. The original report was commissioned by NADA in order to provide its dealer members (the franchised new-car dealers of America) perspectives on the changing automotive retailing environment. The 2017 report was intended to offer “thought starters” to assist dealers in engaging in strategic planning, looking ahead to roughly 2025.1 In early 2019 NADA determined it was time to update the report, as the environment was continuing to shift. The present document is that update: It represents the findings of new work conducted between May and December of 2019. As about two and a half years have passed since the original DOT, focused on 2025, was issued, this update looks somewhat further out, to the late 2020s. Disclaimers As before, we need to make a few things clear at the outset: 1. In every case we have tried to link our forecast to specific implications for dealers. There is much to be said about the impact of things like electric vehicles and connected cars on society, congestion, the economy, etc. But these impacts lie far beyond the scope of this report, which in its focus on dealerships is already significant in size. Readers are encouraged to turn to academic, consulting, governmental and NGO reports for discussion of these broader issues. -

Kjell Qvale Dies at 94; Married U.S. to Sports Cars - the New York Times

9/21/2020 Kjell Qvale Dies at 94; Married U.S. to Sports Cars - The New York Times https://nyti.ms/183z3Rp Kjell Qvale Dies at 94; Married U.S. to Sports Cars By Douglas Martin Nov. 12, 2013 Kjell Qvale, who fell in love with a forest-green, wire-wheel MG sports car in the 1940s and went on to become one of the earliest American importers of European cars, ultimately selling a million automobiles as a distributor and dealer, died on Nov. 1 in San Francisco. He was 94. His family announced the death. As a recently discharged Navy veteran, the Norwegian-born Kjell Qvale (pronounced shell KAH-vah-leh) entered the car business in 1946, using $8,500 in savings to invest in a Jeep dealership in Alameda, Calif. He had no particular passion for cars at the time; to him, this was strictly a business proposition. It was also strictly business when he made a trip to New Orleans to meet with an importer to discuss expanding his line by adding James motorcycles, a not-terribly-fast British make known for its Jeep-like practicality. There, Mr. Qvale found himself standing on a street corner when “this goofy-looking car pulls up to the curb in front of me,” he said in an interview in 2008. He asked the driver where it was made. “England,” the driver said. The car was the MG, and the driver turned out to be the importer of motorcycles he had come to see. He gave Mr. Qvale a ride. It also turned out that the importer was looking for someone to market MGs in Northern California. -

The Detomaso Mangusta an Italian Exotic That Happened by Accident

The DeTomaso Mangusta An Italian exotic that happened by accident.. By Rick Feibusch In the good old days, years before the implementation of emissions and safety laws, exotic high-performance automakers woul d just build a car, display it at a few key international auto shows and start taking orders. There wasn't even a legal requirement that the manufacturer road test a prototype before the first production models were delivered to the public! Italian automakers were particularly prone to using the public to test their cars - after delivery. The DeTomaso Mangusta was a particularly interesting example. The Mangusta was born out of the ambition of Argentinian race driver Alejandro De Tomaso who, like many othe r racers, yearned to build his own cars. DeTomaso was born to a wealthy family in a small town near Buenos Aires. He left Argentina in 1955, just one step ahead of Juan Peron's goon squads, having offended the great dictator with political writings publi shed in a local newspaper. Peron, like his idol Adolph Hitler, loved sports cars and heavily supported successful drivers like Juan Manuel Fangio because he believed that if drivers from his country won races, it showed a national superiority. Since DeTomaso wouldn't play ball, he was excluded from the gravy train. DeTomaso left for Italy, the land of his grandparents with only $126 in his racing jumpsuit He met Isabelle Haskell, a rich American woman who owned and raced a Siata and a Maserati. In those d ays, women racers were a rare and unproven commodity, and Ms. -

New Product Ranges from Ebc Brakes Racing for 2021

NEW PRODUCT RANGES FROM EBC BRAKES RACING FOR 2021 Contact Steve for detailed catalog and pricing: [email protected] Unparalleled Braking Performance Introduction to EBC Brakes Racing The EBC Brakes Racing sub-division was formed in 2015 as EBC’s response to the growing trackday and race market. Over the past 35 years, EBC Brakes has become a world leader in the performance road and intermediate trackday market, establishing itself as the go-to brand for car enthusiasts all around the world looking to upgrade their vehicle’s brakes with quality UK made parts at justified prices. The mission statement when establishing the EBC Racing division was a simple one; to combine a no-compromise approach with over 35 years experience in brake science to engineer braking products of the finest quality, that offer unparalleled levels of performance. With modern vehicles becoming increasingly heavy, coupled with ever higher power outputs, the demand placed on the brake system is higher than ever, particularly during on-track driving. Many stock brake systems are simply inadequate for high-performance driving and track use, especially in cases where the vehicle has been tuned. EBC Racing’s product line-up consists of several options that cater for fast road cars right up to full race applications, from our highest ever performing pad compounds RP-1 and RP-X through to our technology-rich EBC Apollo Big Brake Kits, we have precisely engineered and rigorously tested our products to ensure they meet our exacting standards and can reliably withstand the stresses encountered during the most extreme driving. -

Alan and Richard Jensen Produced Their First Car in 1928 When They

Alan and Richard Jensen produced their first car in 1928 when they converted a five year old Austin 7 Chummy Saloon into a very stylish two seater with cycle guards, louvred bonnet and boat-tail. This was soon sold and replaced with another Austin 7. Then came a car produced on a Standard chassis followed by a series of specials based on the Wolseley Hornet, a popular sporting small car of the time. The early 1930s saw the brothers becoming joint managing directors of commercial coachbuilders W J Smith & Sons and within three years the name of the company was changed to Jensen Motors Limited. Soon bodywork conversions followed on readily available chassis from Morris, Singer, Standard and Wolseley. Jensen’s work did not go unnoticed as they received a commission from actor Clark Gable to produced a car on a US Ford V8 chassis. This stylish car led to an arrangement with Edsel Ford for the production of a range of sports cars using a Jensen designed chassis and powered by Ford V8 engines equipped with three speed Ford transmissions. Next came a series of sporting cars powered by the twin-ignition straight eight Nash engine or the Lincoln V12 unit. On the commercial side of the business Jensen’s were the leaders in the field of the design and construction of high-strength light alloys in commercial vehicles and produced a range of alloy bodied trucks and busses powered by either four-cylinder Ford engines, Ford V8s, or Perkins diesels. World War Two saw sports car production put aside and attentions were turned to more appropriate activities such as producing revolving tank gun turrets, explosives and converting the Sherman Tank for amphibious use in the D-Day invasion of Europe. -

40 Jahre Sportwagen Mit Lotus-Herz

06. Jan. 2013 Ausgabe 101/01 JENSEN HEALEY 40 Jahre Sportwagen mit Lotus-Herz KURZNACHRICHTEN TIPPS & TRICKS MODELL DES MONATS Sunday Gazette 101/2012 JENSENHEALEY 40 Jahre Sportwagen mit Lotus-Herz AUTOR: Kay MacKenneth Vereinigungen berühmter Namen gab es in der Automobilgeschichte immer wie- der. Rolls und Royce, Mercedes und Benz sind gängige Beispiele dafür. Weniger bekannt ist das Produkt des Zusammenschlusses von Jensen und Healey. Das blaue Blut des Britischen Sportwagens gesellte sich zum damals neusten Stan- dard automobiler Ingenieurskunst. In unseren Breitengraden ist der Jensen-Healey ein seltener Oldtimer, denn konzipiert war der Sportwagen für den US-Markt. Sehen SIe hier das Video und lesen Sie mehr ... 2 Sunday Gazette 101/2012 Sehen SIe hier das Video und lesen Sie mehr ... 3 Sunday Gazette 101/2012 Auf der Suche nach dem passenden Motor kam Qvale mit Lotus Boss Colin Chapmann ins Geschäft. Nach einigen Startschwierig- keiten, die den Jensen Healey Mark I. mit dem Ruf der Unzuver- lässigkeit belegten, startete man 1973 nochmals durch mit der überarbeiteten Mark 2 Motorversion. 4 Sunday Gazette 101/2012 5 Sunday Gazette 98/2012101/2012 6 Sunday Gazette 101/2012 Präsentiert wurde der Jensen-Healey der Öffentlichkeit 1972. Vo- rangegangen war die Bemühung des US-Importeurs Kjell Qvale nach einem neuen ‚Volumenmodell‘ anstelle des auslaufenden Austin Healeys-Modells, dessen Karosserien bisher als Auftrags- arbeit im Jensen Motors Werk West Bromwich gebaut wurden. Qvale sah seine Chance: Warum nicht selbst bauen, selbst ver- markten und die Fahrzeuge selbst verkaufen? 7 Sunday Gazette 101/2012 In Deutschland ist der zweisitzige Sportwagen mit seinem einfa- chen Stoffverdeck und der reduzierten Innenausstattung eine Seltenheit. -

H:\My Documents\Article.Wpd

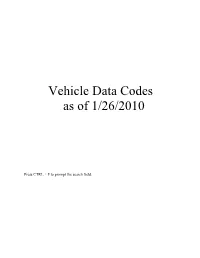

Vehicle Data Codes as of 1/26/2010 Press CTRL + F to prompt the search field. VEHICLE DATA CODES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1--LICENSE PLATE TYPE (LIT) FIELD CODES 1.1 LIT FIELD CODES FOR REGULAR PASSENGER AUTOMOBILE PLATES 1.2 LIT FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 1.3 LIT FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES AND SNOWMOBILES 1.4 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 1.5 LIT FIELD CODES FOR SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 2--VEHICLE MAKE (VMA) AND BRAND NAME (BRA) FIELD CODES 2.1 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES 2.2 VMA, BRA, AND VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, LIGHT- DUTY TRUCKS, AND PARTS 2.3 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.4 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT AND FARM EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.5 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR MOTORCYCLES AND MOTORCYCLE PARTS 2.6 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR SNOWMOBILES AND SNOWMOBILE PARTS 2.7 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRAILERS AND TRAILER PARTS 2.8 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRUCKS AND TRUCK PARTS 2.9 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES ALPHABETICALLY BY CODE 3--VEHICLE MODEL (VMO) FIELD CODES 3.1 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, AND LIGHT-DUTY TRUCKS 3.2 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ASSEMBLED VEHICLES 3.3 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 3.4 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES 3.5 VMO FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT 3.6 VMO FIELD CODES FOR DUNE BUGGIES 3.7 VMO FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT 3.8 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GO-CARTS 3.9 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GOLF CARTS 3.10 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED RIDE-ON TOYS 3.11 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED WHEELCHAIRS 3.12