The Significance of the Automobile in 20Th C. American Short Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VW Executive Had a Pivotal Role As Car Maker Struggled with Emissions by DANNY HAKIM and JACK EWINGDEC

The New York Times 12/21/15 Page | 1 VW Executive Had a Pivotal Role as Car Maker Struggled With Emissions By DANNY HAKIM and JACK EWINGDEC. 21, 2015 Photo Wolfgang Hatz at the 2013 Geneva Car Show. Mr. Hatz, head of transmission and engine development at the Volkswagen Group, was suspended in September. CreditDenis Balibouse/Reuters LONDON — A few months after taking over engine development at Volkswagen in 2007, Wolfgang Hatz faced a potential challenge that he considered insurmountable. It was the State of California. Regulators there were seeking to limit global warming gases released by automobiles, a step never directly taken before in the United States. “We can do quite a bit and we will do a bit, but ‘impossible’ we cannot do,” Mr. Hatz said during a trip to San Francisco that year, where he http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/22/business/international/vw‐executive‐had‐a‐pivotal‐role‐as‐car‐ maker‐struggled‐with‐emissions.html?_r=0 The New York Times 12/21/15 Page | 2 took part in a technology demonstration hosted byVolkswagen. “From my point of view, the C.A.R.B. is not realistic,” he said of the California Air Resources Board, in remarks filmed by an auto website during the event. Of the proposed regulation, he said, “I see it as nearly impossible for us.” In September of this year, Volkswagen, then the world’s largest automaker, admitted to installing software designed to cheat on emissions tests, setting off one of the largest corporate scandals in the industry’s history. The role of Mr. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This

Theologica Xaveriana ISSN: 0120-3649 ISSN: 2011-219X [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Colombia Poggi, Alfredo Ignacio A Southern Gothic Theology: Flannery O’Connor and Her Religious Conception of the Novel∗ Theologica Xaveriana, vol. 70, 2020, pp. 1-23 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Colombia DOI: https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.tx70.sgtfoc Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=191062490018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative doi: https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.tx70.sgtfoc A Southern Gothic Theology: Una teología gótica sureña: Flannery O’Connor y su concepción religiosa de la Flannery O’Connor and novela Her Religious Conception Resumen: Mary Flannery O’Connor, a ∗ menudo considerada una de las mejores of the Novel escritoras norteamericanas del siglo XX, parece haber respaldado la existencia de la a “novela católica” como género particular. Alfredo Ignacio Poggi Este artículo muestra las características University of North Georgia descritas por O’Connor sobre este género, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9663-3504 puntualizando la constitución indefinida y problemática de dicha delimitación. Independientemente de la imposibilidad RECIBIDO: 30-07-19. APROBADO: 18-02-20 de definir el término, este artículo sostiene además que la explicación de O’Connor sobre el género trasciende el campo lite- rario y muestra una visión distintiva de Abstract: Mary Flannery O’Connor, often consi- la fe cristiana y una teología sofisticada dered one of the greatest North American writers of que denomino “gótico sureño”. -

Flannery O'connor

ANALYSIS “The Artificial Nigger” (1955) Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) “I suppose ‘The Artificial Nigger’ is my favorite…. And there is nothing that screams out the tragedy of the South like what my uncle calls ‘nigger statuary.’ And then there’s Peter’s denial. They all got together in that one. You are right about this negativity being in large degree personal. My disposition is a combination of Nelson’s and Hulga’s. Or perhaps I only flatter myself.” O’Connor, Letter (6 September 1955) “Well, I never had heard the phrase before, but my mother was out trying to buy a cow, and she rode up the country a-piece. She had the address of a man who was supposed to have a cow for sale, but she couldn’t find it, so she stopped in a small town and asked the countryman on the side of the road where the house was, and he said, ‘Well, you go into this town and you can’t miss it ‘cause it’s the only house in town with a artificial nigger in front of it.’ So I decided I would have to find a story to fit that.” O’Connor, Symposium, Vanderbilt U (1957) “’The Artificial Nigger’ is my favorite and probably the best thing I’ll ever write.” O’Connor, Letter (10 March 1957) “We begin here with nothing more uncommon than a rustic old man taking his rustic grandson for his first trip to the city. While their backwoodness is a bit grotesque and the old man’s vanity provides touching humor, metaphysical drama doesn’t overturn secular seeming until the man publicly denies his relationship to the boy to escape retribution and to give the humor a new dimension. -

BA Thesis O'connor

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE – FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV ANGLOFONNÍCH LITERATUR A KULTUR The Conflict of Country and City in Flannery O’Connor’s Short Stories BAKALÁ ŘSKÁ PRÁCE Vedoucí bakalá řské práce (supervisor): doc. Clare Wallace, PhD, M.A. Zpracoval (author): Anna Hejzlarová Studijní obor (subject): Anglistika a amerikanistika Praha, 14.1.2013 i Declaration Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalá řskou práci vypracoval/a samostatně, že jsem řádn ě citoval/a všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného či stejného titulu. I declare that the following BA thesis is my own work for which I used only the sources and literature mentioned, and that this thesis has not been used in the course of other university studies or in order to acquire the same or another type of diploma. V Praze dne 14.1.2013 Anna Hejzlarová ii Permission Souhlasím se zap ůjčením bakalá řské práce ke studijním ú čel ům. I have no objections to the BA thesis being borrowed and used for study purposes. iii Acknowledgements Tímto bych ráda pod ěkovala doc. Clare Wallace, PhD, M.A., za cenné rady, trp ělivost a vedení, jež mi pomohly p ři psaní a formování této práce. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to doc. Clare Wallace, PhD, M.A., for her valuable advice, patience, and guidance, which helped me to write and shape this thesis. iv Table of Contents Declaration .................................................................................................................................ii -

Flannery O'connor's Images of the Self

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 1978 CLOWNS AND CAPTIVES: FLANNERY O'CONNOR'S IMAGES OF THE SELF MICHAEL JOHN LEE Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation LEE, MICHAEL JOHN, "CLOWNS AND CAPTIVES: FLANNERY O'CONNOR'S IMAGES OF THE SELF" (1978). Doctoral Dissertations. 1210. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1210 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document ' ave been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Elizabeth Treadway

AMERICAN PUBLIC WORKS ASSOCIATION • SEPTEMBER 2012 • www.apwa.net Elizabeth Treadway takes the helm of APWA The All-New APWA Members’ Library More than 350 recorded Public Works Education Sessions Hundreds of articles, publications, videos, and more All at your fingertips, 24/7/365 www.apwa.net/memberslibrary September 2012 Vol. 79, No. 9 The APWA Reporter, the official magazine of the American Public Works Association, covers all facets of public works for APWA members including industry news, legislative actions, management issues and emerging technologies. FLEET SERVICES ISSUE INSIDE APWA 2 President’s Message 8 Technical Committee News 9 Recognize Your Leaders 10 The mentors of the APWA Donald C. Stone Center 12 Celebrating National Public Works Week 2012 with Southern Charm 16 City of San Antonio Disability Access Office 18 Employee Recognition 20 Fleet Services Committee announces new replacement planning publication 30 22 CPFP Campbell named Fleet Manager of the Year COLUMNS 6 Washington Insight 24 The Great 8 28 Global Solutions in Public Works 58 Ask Ann FEATURES 34 34 City of Ames, Iowa: Police cars replaced by need, not by time or miles 38 Road map to fleet success 42 How to reach out to the media 44 Fleet consolidation 48 Purchasing and installing publicly-accessible electric vehicle charging stations 52 Tool policies for employees 54 Six purchasing tips for fleet professionals 56 Trucking USA WORKZONE 38 56 WorkZone: Your Connection to Public Works Careers MARKETPLACE 60 Products in the News 65 Professional Directory CALENDARS 5 Education Calendar 68 World of Public Works Calendar 68 49 Index of Advertisers September 2012 APWA Reporter 1 Our profession has stepped up Elizabeth Treadway, PWLF APWA President Editor’s Note: As has become tradition, 2009-11), and most recently co-chaired each new APWA President is interviewed the Certification and Professional by the APWA Reporter at the beginning Development Group. -

Region, Idolatry, and Catholic Irony: Flannery O'connor's Modest Literary Vision

01-logos-jackson-pp13-40 2/8/02 3:51 PM Page 13 Robert Jackson Region, Idolatry, and Catholic Irony: Flannery O’Connor’s Modest Literary Vision Introduction:On Adolescence and Authority,Region,and Religion Writing to his lifelong friend Walker Percy in 1969, the Mis- sissippi novelist and historian Shelby Foote assessed the life and career of their contemporary and fellow Southerner Flannery O’Connor: She had the real clew, the solid gen, on what it’s about; I just wish she’d had time to demonstrate it fully instead of in frag- ments. She’s a minor-minor writer,not because she lacked the talent to be a major one, but simply because she died before her development had time to evolve out of the friction of just living enough years to soak up the basic joys and sorrows. That, and I think because she also didn’t have time to turn her back on Christ, which is something every great Catholic writer (that I know of, I mean) has done. Joyce, Proust—and, I think, Dostoevsky, who was just about the least Christian man I ever encountered except maybe Hemingway....I always had the feeling that O’Connor was going to be one of our big talents; I didn’t know she was dying—which of course logos 5:1 winter 2002 01-logos-jackson-pp13-40 2/8/02 3:51 PM Page 14 logos means I misunderstood her. She was a slow developer, like most good writers, and just plain didn’t have the time she needed to get around to the ordinary world, which would have been her true subject after she emerged from the “grotesque” one she explored throughout the little time she had.1 Foote’s image of O’Connor is striking not only for what it express- es about her life and writings, but perhaps even more so for its imaginative portrait of the person who might have evolved into a very different writer with age and maturity. -

On the Improvement Measures of Interior Noise Reduction of Minivan's

2560. On the improvement measures of interior noise reduction of minivan’s roof based on acoustic modal analysis Yici Li1, Lin Hua2, Fengxiang Xu3 Hubei Key Laboratory of Advanced Technology for Automotive Components, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan 430070, China Hubei Collaborative Innovation Center for Automotive Components Technology, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan 430070, China 2, 3Corresponding authors E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received 17 November 2016; received in revised form 23 April 2017; accepted 6 May 2017 DOI https://doi.org/10.21595/jve.2017.18030 Abstract. In this work, three types of measures, i.e., 1) adding the damping adhesive, 2) changing the local beads and 3) utilizing the dynamic vibration absorber (DVA), are performed to investigate and improve the acoustic quality of the minivan’s interior noise. For adding the damping adhesive, the difference of the adhesive location directly affects the mode of minivan’s roof. For changing the local beads, eight cases of beads are selected. The results indicate that the change trend of the first natural frequency is parabolic as the number of beads increases. For adding the 33 Hz DVA, the results show that the sound pressure levels (SPLs) of the minivan’s response points located at the front, middle and rear seat in the critical frequency are approximately reduced by 2.1 dB, 1.5 dB and 1.1 dB in the minivan’s simulation, and by 2.6 dB(A), 1.4 dB(A) and 2.7 dB(A) in the minivan’s road experiment, respectively. -

The Dealership of Tomorrow 2.0: America’S Car Dealers Prepare for Change

The Dealership of Tomorrow 2.0: America’s Car Dealers Prepare for Change February 2020 An independent study by Glenn Mercer Prepared for the National Automobile Dealers Association The Dealership of Tomorrow 2.0 America’s Car Dealers Prepare for Change by Glenn Mercer Introduction This report is a sequel to the original Dealership of Tomorrow: 2025 (DOT) report, issued by NADA in January 2017. The original report was commissioned by NADA in order to provide its dealer members (the franchised new-car dealers of America) perspectives on the changing automotive retailing environment. The 2017 report was intended to offer “thought starters” to assist dealers in engaging in strategic planning, looking ahead to roughly 2025.1 In early 2019 NADA determined it was time to update the report, as the environment was continuing to shift. The present document is that update: It represents the findings of new work conducted between May and December of 2019. As about two and a half years have passed since the original DOT, focused on 2025, was issued, this update looks somewhat further out, to the late 2020s. Disclaimers As before, we need to make a few things clear at the outset: 1. In every case we have tried to link our forecast to specific implications for dealers. There is much to be said about the impact of things like electric vehicles and connected cars on society, congestion, the economy, etc. But these impacts lie far beyond the scope of this report, which in its focus on dealerships is already significant in size. Readers are encouraged to turn to academic, consulting, governmental and NGO reports for discussion of these broader issues. -

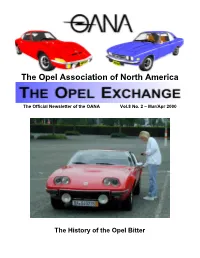

The Opel Association of North America

The Opel Association of North America The Official Newsletter of the OANA Vol.8 No. 2 – Mar/Apr 2000 The History of the Opel Bitter OANA CLUB INFORMATION The Opel Association of North America has been in existence as a local club since 1985. From 1994 to 1996 the club saw many transformations, and the O.A.N.A. settled into its current form in 1996. Our purpose now is to provide a source for locating parts, service, tech-help and various forums to exchange information between owners of all Opel models from the 1957 Olympia to any gray market imports that are in North America. We do, however, place a special emphasis on the Opel GT, Manta and Kadett models. Our ultimate goal is to keep the Opel marquee a presence in North America, improve the collectability of all Opels in North America, and most of all, to have fun doing it. The North American Bitter Registry was formed for essentially the same reasons as The Opel Association. A very small number of Bitters (our sister make) SC coupes were imported into the U.S. With the non-existence of any club to help the owners of these rare and exotic cars, it was determined that our club would be the right place to give assistance and help these owners have a place to get connected. · Club membership dues: Net-Only Membership (Members do not get a mailed newsletter; they download it from the net) is $20 for 2 years. Business members are $100 a year (includes business card in newsletter and banner on front page of web site), $50 per ad page per issue. -

The Displaced Person

BOOKS BY Flannery O'Connor Flannery O'Connor THE NOV E L S Wise Blood COMPLETE The Violent Bear It Away STORIES STORIES A Good Man Is Hard to Find Everything That Rises Must Converge with an introduction by Robert Fitzgerald NON-FICTION Mystery and Manners edited and with an introduction by Robert and SaUy Fitzgerald The Habit of Being edited and with an introduction by Sally Fitzgerald Straus and Giroux New York ~ I Farrar, Straus and Giroux 19 Union Square West, New York 10003 Copyright © 1946, 194il, 195(l, 1957, 1958, 1960, [()61, Hi)2, 1963, 1964,l()65, 1970, 1971 by [he Estate of Mary Flannery O'Connor. © 1949, 1952, [955,1960,1\162 by Contents O'Connor. Introduction copyright © 1971 by Robert Giroux All rights reserved Distributed in Canada by Douglas & McImyre Ltd. Printed in the United States of America First published in J(171 by Farrar, Straus and (;iroux INTRODUCTION by Robert Giroux Vll Quotations from Inters are used by permission of Robert Fitzgerald and of the Estate and are copyright © 197 r by the Estate of Mary Flannery O'Connor. The ten stories The Geranium 3 from A Good ManIs Hard to Find, copyright © [953,1954,1955 by Flannery O'Connor, The Barber 15 arc used by special arrangement with Harcourt Hrace Jovanovich, Inc Wildcat 20 The Crop 33 of Congress catalog card number; 72'171492 The Turkey 42 Paperback ISBN: 0-374-51536-0 The Train 54 The Peeler 63 Designed by Herb Johnson The Heart of the Park ~h A Stroke of Good Fortune 95 Enoch and the Gorilla lOS A Good Man Is Hard to Find II7 55 57 59 61 62 60 58 56 A Late Encounter with the Enemy 134 The Life You Save May Be Your Own 14'5 The River 157 A Circle in the Fire 175 The Displaced Person 194 A Temple of the Holy Ghost The Artificial Nigger 249 Good Country People 27 1 You Can't Be Any Poorer Than Dead 292 Greenleaf 311 A View of the Woods 335 v The Displaced Person / I95 them. -

United States District Court District of Maine Caryl E

Case 1:06-cv-00069-JAW Document 97 Filed 03/28/08 Page 1 of 25 PageID #: 1123 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MAINE CARYL E. TAYLOR, individually and ) as personal representative of the estate of ) MARK E. TAYLOR, ) ) Plaintiff ) ) v. ) Civ. No. 06-69-B-W ) FORD MOTOR COMPANY, ) ) Defendant ) RECOMMENDED DECISION ON DEFENDANT'S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT Caryl Taylor contends that her deceased husband's 2002 Ford F-250 Super Cab pickup truck was defectively designed and that her husband would likely have survived a roll-over event but for alleged defects in the roof and door assemblies. Ms. Taylor never designated a automotive engineer or other design expert to support her claim of design defect. Ford Motor Company argues that this omission calls for judgment in its favor as a matter law and has filed a motion for summary judgment to that effect (Doc. No. 43). The Court referred the motion to me for a recommended decision and based on my review I recommend that the Court grant the motion, in part, based on certain concessions made by Taylor, but not as to the chief contention Ford makes with respect to the need for Taylor to have her own design expert. Facts The following facts are material to the summary judgment motion. They are drawn from the parties' statements of material facts in accordance with Local Rule 56. See Doe v. Solvay Case 1:06-cv-00069-JAW Document 97 Filed 03/28/08 Page 2 of 25 PageID #: 1124 Pharms., Inc., 350 F. Supp.