A Prosodic Account of Consonant Gemination in Japanese Loanwords

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

Problematika České Transkripce Japonštiny a Pravidla Jejího Užívání Nihongo 日本語 社会 Šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová Momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 Čotto ち ょっ と

チェ コ語 翼 čekogo cubasa šin’jó 信用 Problematika české transkripce japonštiny a pravidla jejího užívání nihongo 日本語 社会 šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 čotto ち ょっ と PROBLEMATIKA ČESKÉ TRANSKRIPCE JAPONŠTINY A PRAVIDLA JEJÍHO UŽÍVÁNÍ Ivona Barešová Monika Dytrtová Spolupracovala: Bc. Mária Ševčíková Oponenti: prof. Zdeňka Švarcová, Dr. Mgr. Jiří Matela, M.A. Tento výzkum byl umožněn díky účelové podpoře na specifi cký vysokoškolský výzkum udělené roku 2013 Univerzitě Palackého v Olomouci Ministerstvem školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy ČR (FF_2013_044). Neoprávněné užití tohoto díla je porušením autorských práv a může zakládat občanskoprávní, správněprávní, popř. trestněprávní odpovědnost. 1. vydání © Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová, 2014 © Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, 2014 ISBN 978-80-244-4017-0 Ediční poznámka V publikaci je pro přepis japonských slov užito české transkripce, s výjimkou jejich výskytu v anglic kém textu, kde se objevuje původní transkripce anglická. Japonská jména jsou uváděna v pořadí jméno – příjmení, s výjimkou jejich uvedení v bibliogra- fi ckých citacích, kde se jejich pořadí řídí citační normou. Pokud není uvedeno jinak, autorkami překladů citací a parafrází jsou autorky této práce. V textu jsou použity následující grafi cké prostředky. Fonologický zápis je uveden standardně v šikmých závorkách // a fonetický v hranatých []. Fonetické symboly dle IPA jsou použity v rámci kapi toly 5. V případě, že není nutné zaznamenávat jemné zvukové nuance dané hlásky nebo že není kladen důraz na zvukové rozdíly mezi jed- notlivými hláskami, je jinde v textu, kde je to možné, z důvodu usnadnění porozumění užito namísto těchto specifi ckých fonetických symbolů písmen české abecedy, např. -

7$0,/³(1*/,6+ ',&7,21$5< COMMON SPOKEN TAMIL MADE EASY

7$0,/³(1*/,6+ ',&7,21$5< )RU8VH:LWK &20021632.(17$0,/ 0$'(($6< 7KLUG(GLWLRQ E\ 79$',.(6$9$/8 'LJLWDO9HUVLRQ &+5,67,$10(',&$/&2//(*(9(//25( Adi’s Book, Tamil-English Dictionary. KEY adv. adverb n. noun pron. pronoun v. verb nom. takes nominatve case dat. takes dative case adj. adjective acc. takes accusative case d.b. taked declensional base intr. intransitive tr. transitive neut. neuter imp. impersonal pers. personal incl inclusive excl. exclusive m. masculine f. feminine sing. singular pl. plural w. weak s. strong TAMIL ENGLISH TAMIL ENGLISH KX ZQ become, happen DNN sister (older) KX ZQ happen, become DNNXº arm pit DE\VDP exercise (n.) DºD VQGK measure DE\VDPVHL ZGK exercise (v.) alamaram banyan tree adangu (w.in) obey DºDYXHGX VWKWK measurements (take m.) adangu (w.in) subside alladhu or adhan its P yes DGKDQOHKDL\OH therefore DPYVH no moon DGK same ambadhu fifty DGKLKUDP authority DPP madam DGKLNODLOH early morning DPPWK\U mother adhisayam wonder (n.) ammi grindstone adhu it ¼ male adhu (pron. neut.) that Q but DGKXNNXWKKXQGKSÀOD accordingly anai dam adhunga their (neut.) DQVLDQFKL pine apple adhunga they (things) DQEXQVDP love, kindness adhunga those (things)(are) QGDYDU Lord DGKXQJDºH them (things) andha (adj) that adi (s.thth) strike andha (pron.neut.) those adikkadi often DQKD many GX goat, sheep DQKDP almost, mostly aduppu oven, stove ange there aduththa next DQJHGKQ there only ahalam width anju five ahappadu (w.tt) caught, (to be) found D¼¼DQ brother (elder) DK\DYLPQDP aeroplane anumadhi permission (n.) K\DPYQXP sky anumadhi permit (n.) LSÀFKFKX FRO finished anumadhi kodu (s.thth) permit (v.) DLQQÌUX five hundred anuppu (w.in) send LSÀ ZQ exhaust, finish apdi that way DL\ sir DSGLGKQ that is it DL\À oh dear DSGL\ indeed?, is that so? DL\ÀSYDP poor soul! DSGL\" really?, right? DNN elder sister DSSWKDKDSSDQ father Adi’s Book, Tamil-English Dictionary. -

Prosodic Processes in Language and Music

Prosodic Processes in Language and Music Maartje Schreuder Copyright © 2006 by Maartje Schreuder Cover design: Hanna van der Haar Printed by Print Partners Ipskamp, Enschede The work in this thesis has been carried out under the auspices of the Research School of Behavioral and Cognitive Neurosciences (BCN), Groningen Groningen Dissertations in Linguistics 60 ISSN 0928-0030 ISBN 90-367-2637-9 RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN Prosodic Processes in Language and Music Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Letteren aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 15 juni 2006 om 13:15 uur door Maartje Johanneke Schreuder geboren op 25 augustus 1974 te Groningen Promotor: Prof. dr. J. Koster Copromotor: Dr. D.G. Gilbers Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. dr. J. Hoeksema Prof. dr. C. Gussenhoven Prof. dr. P. Hagoort Preface Many people have helped me to finish this thesis. First of all I am indebted to my supervisor Dicky Gilbers. Throughout this disseration, I speak of ‘we’. That is not because I have some double personality which allows me to do all the work in collaboration, but because Dicky was so enthusiastic about the project that we did all the experiments together. The main chapters are based on papers we wrote together for conference proceedings, books, and journals. This collaboration with Dicky always was very motivating and pleasant. I will never forget the conferences we visited together, especially the fun we had trying to find our way in Vienna, and through the subterranean corridors in the castle in Imatra, Finland. -

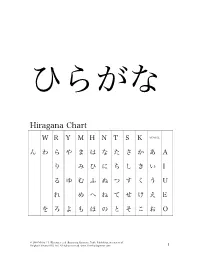

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Galio Uma, Maƙerin Azurfa Maƙeri (M): Ni Ina Da Shekara Yanzu…

LANGUAGE PROGRAM, 232 BAY STATE ROAD, BOSTON, MA 02215 [email protected] www.bu.edu/Africa/alp 617.353.3673 Interview 2: Galio Uma, Maƙerin Azurfa Maƙeri (M): Ni ina da shekara yanzu…, ina da vers …alal misali vers mille neuf cent quatre vingt et quatre (1984) gare mu parce que wajenmu babu hopital lokacin da anka haihe ni ban san shekaruna ba, gaskiya. Ihehehe! Makaranta, ban yi makaranta ba sabo da an sa ni makaranta sai daga baya wajenmu babana bai da hali, mammana bai da hali sai mun biya. Akwai nisa tsakaninmu da inda muna karatu. Kilometir kama sha biyar kullum ina tahiya da ƙahwa. To, ha na gaji wani lokaci mu hau jaki, wani lokaci mu hau raƙumi, to wani lokaci ma babu hali, babu karatu. Amman na yi shekara shidda ina karatu ko biyat. Amman ban ji daɗi ba da ban yi karatu ba. Sabo da shi ne daɗin duniya. Mm. To mu Buzaye ne muna yin buzanci. Ana ce muna Tuareg. Mais Tuareg ɗin ma ba guda ba ne. Mu artisans ne zan ce miki. Can ainahinmu ma ba mu da wani aiki sai ƙira. Duka mutanena suna can Abala. Nan ga ni dai na nan ga. Ka gani ina da mata, ina da yaro. Akwai babana, akwai mammana. Ina da ƙanne huɗu, macce biyu da namiji biyu. Suna duka cikin gida. Duka kuma kama ni ne chef de famille. Duka ni ne ina aider ɗinsu. Sabo da babana yana da shekara saba’in da biyar. Vers. Mammana yana da shekara shi ma hamsin da biyar. -

Na Kana Magiti Kei Na Lotu

1 NA KANA MAGITI KEI NA LOTU (Vola Tabu : Maciu 22:1-10; Luke 14:12-24) Vola ko Rev. Dr. Ilaitia S. Tuwere. Sa inaki ni vunau oqo me taroga ka sauma talega na taro : A cava na Lotu? Ni da tekivu edaidai ena noda solevu vakalotu, sa na yaga meda taroga ka tovolea talega me sauma na taro oqori. Ia, ena levu na kena isau eda na solia, me vaka na: gumatuataki ni masu kei na vulici ni Vola Tabu, bula vakayalo, muria na ivakarau se lawa ni lotu ka vuqa tale. Na veika oqori era ka dina ka tu kina eso na isau ni taro : A Cava na Lotu. Na i Vola Tabu e sega ni tuvalaka vakavosa vei keda na ibalebale ni lotu. E vakavuqa me boroya vei keda na iyaloyalo me vakadewataka kina na veika eso e vinakata me tukuna. E sega talega ni solia e duabulu ga na iyaloyalo me baleta na lotu. E vuqa sara e solia vei keda. Oqori me vaka na Qele ni Sipi kei na i Vakatawa Vinaka; na Vuni Vaini kei na Tabana; na i Vakavuvuli kei iratou na nona Gonevuli se Tisaipeli, na Masima se Rarama kei Vuravura, na Ulu kei na Vo ni Yago taucoko, ka vuqa tale. Ena mataka edaidai, meda raica vata yani na iyaloyalo ni kana magiti. E rua na kena ivakamacala eda rogoca, mai na Kosipeli i Maciu kei na nei Luke. Na kana magiti se na solevu edua na ivakarau vakaitaukei. Eda soqoni vata kina vakaveiwekani ena noda veikidavaki kei na marau, kena veitalanoa, kena sere kei na meke, kena salusalu kei na kumuni iyau. -

On the Theoretical Implications of Cypriot Greek Initial Geminates

<LINK "mul-n*">"mul-r16">"mul-r8">"mul-r19">"mul-r14">"mul-r27">"mul-r7">"mul-r6">"mul-r17">"mul-r2">"mul-r9">"mul-r24"> <TARGET "mul" DOCINFO AUTHOR "Jennifer S. Muller"TITLE "On the theoretical implications of Cypriot Greek initial geminates"SUBJECT "JGL, Volume 3"KEYWORDS "geminates, representation, phonology, Cypriot Greek"SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> On the theoretical implications of Cypriot Greek initial geminates* Jennifer S. Muller The Ohio State University Cypriot Greek contrasts singleton and geminate consonants in word-initial position. These segments are of particular interest to phonologists since two divergent representational frameworks, moraic theory (Hayes 1989) and timing-based frameworks, including CV or X-slot theory (Clements and Keyser 1983, Levin 1985), account for the behavior of initial geminates in substantially different ways. The investigation of geminates in Cypriot Greek allows these differences to be explored. As will be demonstrated in a formal analysis of the facts, the patterning of geminates in Cypriot is best accounted for by assuming that the segments are dominated by abstract timing units such as X- or C-slots, rather than by a unit of prosodic weight such as the mora. Keywords: geminates, representation, phonology, Cypriot Greek 1. Introduction Cypriot Greek is of particular interest, not only because it is one of the few varieties of Modern Greek maintaining a consonant length contrast, but more importantly because it exhibits this contrast in word-initial position: péfti ‘Thursday’ vs. ppéfti ‘he falls’.Although word-initial geminates are less common than their word-medial counterparts, they are attested in dozens of the world’s languages in addition to Cypriot Greek. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Legacy Character Sets & Encodings

Legacy & Not-So-Legacy Character Sets & Encodings Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/cjkv/unicode/iuc15-tb1-slides.pdf Tutorial Overview dc • What is a character set? What is an encoding? • How are character sets and encodings different? • Legacy character sets. • Non-legacy character sets. • Legacy encodings. • How does Unicode fit it? • Code conversion issues. • Disclaimer: The focus of this tutorial is primarily on Asian (CJKV) issues, which tend to be complex from a character set and encoding standpoint. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations dc • GB (China) — Stands for “Guo Biao” (国标 guóbiâo ). — Short for “Guojia Biaozhun” (国家标准 guójiâ biâozhün). — Means “National Standard.” • GB/T (China) — “T” stands for “Tui” (推 tuî ). — Short for “Tuijian” (推荐 tuîjiàn ). — “T” means “Recommended.” • CNS (Taiwan) — 中國國家標準 ( zhôngguó guójiâ biâozhün) in Chinese. — Abbreviation for “Chinese National Standard.” 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • GCCS (Hong Kong) — Abbreviation for “Government Chinese Character Set.” • JIS (Japan) — 日本工業規格 ( nihon kôgyô kikaku) in Japanese. — Abbreviation for “Japanese Industrial Standard.” — 〄 • KS (Korea) — 한국 공업 규격 (韓國工業規格 hangug gongeob gyugyeog) in Korean. — Abbreviation for “Korean Standard.” — ㉿ — Designation change from “C” to “X” on August 20, 1997. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • TCVN (Vietnam) — Tiu Chun Vit Nam in Vietnamese. — Means “Vietnamese Standard.” • CJKV — Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated What Is A Character Set? dc • A collection of characters that are intended to be used together to create meaningful text.