Technology and Aging in America (Part 14 Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Version

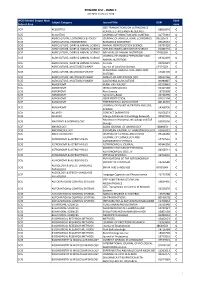

REWARD LIST ‐ RANK C JCR 2018 ‐CiteScore 2018 WOS Edition/ Scopus Main Rank Subject Category Journal Title ISSN Subject Area code IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON ULTRASONICS SCIE ACOUSTICS 08853010 C FERROELECTRICS AND FREQUENCY SCIE ACOUSTICS JOURNAL OF VIBRATION AND CONTROL 10775463 C SCIE AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS & POLICY JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS 0021857X C SCIE AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING BIOMASS & BIOENERGY 09619534 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE ANIMAL REPRODUCTION SCIENCE 03784320 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE APPLIED ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR SCIENCE 01681591 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE ARCHIVES OF ANIMAL NUTRITION 1745039X C JOURNAL OF ANIMAL PHYSIOLOGY AND SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE 09312439 C ANIMAL NUTRITION SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE Animals 20762615 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, MULTIDISCIPLINARY Journal of Land Use Science 1747423X C RENEWABLE AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SCIE AGRICULTURE, MULTIDISCIPLINARY 17421705 C SYSTEMS SCIE AGRICULTURE, MULTIDISCIPLINARY ANNALS OF APPLIED BIOLOGY 00034746 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, MULTIDISCIPLINARY CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURE 00080845 C SCIE AGRONOMY PLANT PATHOLOGY 00320862 C SCIE AGRONOMY IRRIGATION SCIENCE 03427188 C SCIE AGRONOMY Rice Science 16726308 C SCIE AGRONOMY Agronomy‐Basel 20734395 C SCIE AGRONOMY CROP PROTECTION 02612194 C SCIE AGRONOMY EXPERIMENTAL AGRICULTURE 00144797 C JOURNAL OF PLANT NUTRITION AND SOIL SCIE AGRONOMY 14368730 C SCIENCE SCIE ALLERGY CONTACT DERMATITIS 01051873 C SCIE ALLERGY Allergy Asthma & Immunology Research 20927355 C Advances -

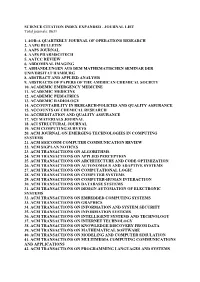

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Jennifer I. Luebke 1 Curriculum Vitae Jennifer I. Luebke, Ph.D. Associate

Jennifer I. Luebke Curriculum Vitae Jennifer I. Luebke, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Anatomy & Neurobiology Associate Professor of Psychiatry Director, Laboratory of Cellular Neurobiology Boston University School of Medicine 85 East Newton Street, M949 Boston, Massachusetts 02118 Voice: 617-638-4930 Email: [email protected] Education and Employment History: 1980-1984: B.S. (Biology) Randolph-Macon College, Ashland, Virginia 1984-1986: Laboratory Technician (Laboratory of Cell Biology and Genetics, NIDDK) National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 1986-1990: Ph.D. Student (Anatomy & Neurobiology), Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts (Linda L. Wright, mentor) 1990-1992: Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Robert W. McCarley and Robert W. Greene mentors) 1992-1995: Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Physiology, Tufts University Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Kathleen Dunlap, mentor) 1995-2003: Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy & Neurobiology and Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 2004-Present: Associate Professor, Department of Anatomy & Neurobiology and Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 2010-Present: Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Neuroscience, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York Research Summary: Research is directed toward understanding alterations in the structure and function of individual cortical pyramidal cells in a rhesus monkey model of normal aging and in transgenic mouse models of neurodegenerative disease. Using whole-cell patch-clamp methods and ultra-high resolution confocal microscopy, Dr. Luebke has demonstrated marked alterations in action potential firing patterns (and underlying ionic currents), glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic response properties and detailed dendritic and spine architecture in cortical pyramidal cells both in normal aging and in mouse models of neurodegenerative disease. -

Predicting Cognitive Decline: Genetic, Environmental and Lifestyle Risk Factors

Predicting Cognitive Decline: Genetic, Environmental and Lifestyle Risk Factors Shea J. Andrews April 2017 A thesis by compilation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University © Copyright by Shea John Frederick Andrews 2017 All Rights Reserved i Declaration This work was conducted from February 2013 to August 2016 at the Genome Diversity and Health Group, John Curtin School of Medical Research, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT. This thesis by compilation consists of five original publications describing the analyses I have performed during my candidature investigating the role of genetic, environmental and lifestyle risk factors in normal cognitive aging. All five publications have been published in Q1 ranked journals according to the SCImago Journal & Country Rankings in the fields of neurology, genetics, psychiatry and mental health, and geriatric and gerontology. My specific contribution to each manuscript is detailed in the subsequent pages in the form of a statement signed by the senior author of each publication. This document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Shea Andrews Canberra, Australia April 2017 ii Published Papers Andrews, SJ, Das, D., Anstey, KJ., Easteal, S. (2015). Interactive effect of APOE genotype and blood pressure on cognitive decline: The PATH through life project. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 44(4): 1087-98. DOI: 10.3233/JAD- 140630 For this publication, I designed and performed all statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. A slightly modified version of this paper is presented in Chapter 3. ____________________ Simon Easteal Senior Author April 2017 Andrews SJ, Das D, Cherbuin N, Anstey KJ, Easteal S. -

Brain Ageing in the New Millennium

Brain ageing in the new millennium Julian N. Trollor, Michael J. Valenzuela Objective: This paper examines the current literature pertaining to brain ageing. The objective of this review is to provide an overview of the effects of ageing on brain structure and function and to examine possible mediators of these changes. Methods: A MEDLINE search was conducted for each area of interest. A selective review was undertaken of relevant articles. Results: Although fundamental changes in fluid intellectual abilities occur with age, global cognitive decline is not a hallmark of the ageing process. Decline in fluid intellectual ability is paralleled by regionally specific age related changes apparent from both structural and functional neuroimaging studies. The histopathological mediators of these changes do not appear to be reduction in neuronal number, which, with the exception of selected hippo- campal regions, remain relatively stable across age. At the molecular level, several mech- anisms of age related change have been postulated. Such theoretical models await refinement and may eventually provide a basis for therapy designed to reduce effects of the ageing process. The role of possible protective factors such as ‘brain reserve’, neuro- protective agents and hormonal factors in modifying individual vulnerability to the ageing process has been the focus of a limited number of studies. Conclusion: Our understanding of the functional and structural changes associated with both healthy and pathological ageing is rapidly gaining in sophistication and complexity. An awareness of the fundamental biological substrates underpinning the ageing process will allow improved insights into vulnerability to neuropsychiatric disease associated with advancing age. Key words: brain ageing, cognition, dementia, neuroimaging. -

The Effects of Normal Aging on Myelin and Nerve Fibers: a Review∗

Journal of Neurocytology 31, 581–593 (2002) The effects of normal aging on myelin and nerve fibers: A review∗ ALAN PETERS Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Boston University School of Medicine, 715, Albany Street, Boston, MA 02118, USA [email protected] Received 7 January 2003; revised 4 March 2003; accepted 5 March 2003 Abstract It was believed that the cause of the cognitive decline exhibited by human and non-human primates during normal aging was a loss of cortical neurons. It is now known that significant numbers of cortical neurons are not lost and other bases for the cognitive decline have been sought. One contributing factor may be changes in nerve fibers. With age some myelin sheaths exhibit degenerative changes, such as the formation of splits containing electron dense cytoplasm, and the formation on myelin balloons. It is suggested that such degenerative changes lead to cognitive decline because they cause changes in conduction velocity, resulting in a disruption of the normal timing in neuronal circuits. Yet as degeneration occurs, other changes, such as the formation of redundant myelin and increasing thickness suggest of sheaths, suggest some myelin formation is continuing during aging. Another indication of this is that oligodendrocytes increase in number with age. In addition to the myelin changes, stereological studies have shown a loss of nerve fibers from the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres of humans, while other studies have shown a loss of nerve fibers from the optic nerves and anterior commissure in monkeys. It is likely that such nerve fiber loss also contributes to cognitive decline, because of the consequent decrease in connections between neurons. -

Integrated Transcriptomic and Neuroimaging Brain Model Decodes

RESEARCH ARTICLE Integrated transcriptomic and neuroimaging brain model decodes biological mechanisms in aging and Alzheimer’s disease Quadri Adewale1,2,3, Ahmed F Khan1,2,3, Felix Carbonell4, Yasser Iturria-Medina1,2,3*, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative† 1Neurology and Neurosurgery Department, Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Canada; 2McConnell Brain Imaging Centre, Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Canada; 3Ludmer Centre for Neuroinformatics and Mental Health, McGill University, Montreal, Canada; *For correspondence: 4Biospective Inc, Montreal, Canada [email protected] †Data used in preparation of this article were partly obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Abstract Both healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are characterized by concurrent Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) alterations in several biological factors. However, generative brain models of aging and AD are database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As limited in incorporating the measures of these biological factors at different spatial resolutions. such, the investigators within the Here, we propose a personalized bottom-up spatiotemporal brain model that accounts for the ADNI contributed to the design direct interplay between hundreds of RNA transcripts and multiple macroscopic neuroimaging and implementation of ADNI modalities (PET, MRI). In normal elderly and AD participants, the model identifies top genes and/or provided data but did not modulating tau and amyloid-b burdens, vascular flow, glucose metabolism, functional activity, and participate in analysis or writing atrophy to drive cognitive decline. The results also revealed that AD and healthy aging share of this report. A complete listing specific biological mechanisms, even though AD is a separate entity with considerably more altered of ADNI investigators can be pathways. -

Download Download

NeuroRegulation The Official Journal of . Volume 8, Number 1, 2021 NeuroRegulation Editor-in-Chief Rex L. Cannon, PhD: SPESA Research Institute, Knoxville, TN, USA Executive Editor Nancy L. Wigton, PhD: 1) Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, AZ, USA; 2) Applied Neurotherapy Center, Tempe, AZ, USA Associate Editors Scott L. Decker, PhD: University of South Carolina, Department of Psychology, Columbia, SC, USA Jon A. Frederick, PhD: Lamar University, Beaumont, TX, USA Genomary Krigbaum, PsyD: University of Wyoming, Family Medicine Residency, Casper, WY, USA Randall Lyle, PhD: Mount Mercy University, Cedar Rapids, IA, USA Tanya Morosoli, MSc: 1) Clínica de Neuropsicología Diagnóstica y Terapéutica, Mexico City, Mexico; 2) ECPE, Harvard T. H. Chan School oF Public Health, Boston, MA, USA Sarah Prinsloo, PhD: MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA Deborah Simkin, MD: 1) Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, Atlanta, GA, USA; 2) Attention, Memory, and Cognition Center, Destin, FL, USA Estate M. Sokhadze, PhD: University of South Carolina, School of Medicine Greenville, Greenville, SC, USA Larry C. Stevens, PhD: Northern Arizona University, Department of Psychological Services, Flagstaff, AZ, USA Tanju Surmeli, MD: Living Health Center for Research and Education, Sisli, Istanbul, Turkey Production Editor Jacqueline Luk Paredes, Phoenix, AZ, USA NeuroRegulation (ISSN: 2373-0587) is published quarterly by the International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR), 13876 SW 56th Street, PMB 311, Miami, FL 33175-6021, USA. Copyright NeuroRegulation is open access with no submission fees or APC (Author Processing Charges). This journal provides immediate open access to its content on the principle that making research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge. -

2020-21 Student Handbook for Pharmacology and Neuroscience

Pharmacology and Neuroscience Student Handbook 2020-2021 The information provided in this document serves to supplement the requirements of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences detailed in the UNTHSC Catalog with requirements specific to the discipline of Pharmacology and Neuroscience. Table of Contents Page Description of the Pharmacology & Neuroscience Discipline ........ 3 Graduate Faculty and Their Research ............................................. 4 Requirements ................................................................................. 18 Required Courses ..................................................................... 18 Journal Club and Seminar Courses .......................................... 18 Works in Progress .................................................................... 18 Elective Courses ....................................................................... 18 Sample Degree Plans ..................................................................... 20 Advancement to Candidacy ........................................................... 23 2 Pharm & Neuro Discipline Handbook (8/6/2020) Pharmacology & Neuroscience Discipline Nathalie Sumien, Ph.D., Graduate Advisor Center for BioHealth Building, Room 517 817-735-2389 [email protected] Graduate Faculty: Barber, Basu, Borgmann, Chaturvedula, Clark, R. Cunningham, Das, Dong, Forster, Gatch, Goulopoulou, Hall, Huang, Jin, Johnson, R. Liu, Y. Liu, Luedtke, Mallet, Nejtek, O’Bryant, Park, Phillips, L. Prokai, K. Prokai, Roane, Salvatore, A. -

Listado De Revistas Extranjeras Homologadas 2019

Código: M304PR03F01 DEPARTAMENTO LISTADO REVISTAS Versión: 04 ADMINISTRATIVO DE CIENCIA, TECNOLOGÍA E HOMOLOGADAS Fecha: 2018-09-20 INNOVACIÓN Página: 1 de 1 No. NOMBRE ISSN CATEGORIA VIGENCIA LISTA_SIR Enero 2019 - Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Journal 1 COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM 0001-0782; 1557-7317 A1 Diciembre 2020 Citation Reports - JCR; Enero 2019 - Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Journal 2 AIAA JOURNAL 0001-1452; 1533-385X A1 Diciembre 2020 Citation Reports - JCR; Enero 2019 - Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Journal 3 AICHE JOURNAL 0001-1541; 1547-5905 A1 Diciembre 2020 Citation Reports - JCR; Enero 2019 - Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Journal 4 AORN JOURNAL 0001-2092; 1878-0369 A2 Diciembre 2020 Citation Reports - JCR; Enero 2019 - 5 Archiv fur Rechts- und Sozialphilosophie 0001-2343 B Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Diciembre 2020 0001-2491; 0364-9962; Enero 2019 - Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Journal 6 ASHRAE JOURNAL B 1943-6637 Diciembre 2020 Citation Reports - JCR; Enero 2019 - 7 Planning 0001-2610 C Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Diciembre 2020 Enero 2019 - Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Journal 8 SEMINARS IN NUCLEAR MEDICINE 0001-2998; 1558-4623 A1 Diciembre 2020 Citation Reports - JCR; Enero 2019 - Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Journal 9 Abacus 0001-3072; 1467-6281 A2 Diciembre 2020 Citation Reports - JCR; Enero 2019 - Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Journal 10 ANAIS DA ACADEMIA BRASILEIRA DE CIENCIAS 0001-3765; 1678-2690 A1 Diciembre 2020 Citation Reports - JCR; Enero 2019 - Scimago Journal Rank - SJR; Journal 11 BULLETIN DE L ACADEMIE NATIONALE DE -

Dr. F. Gonzalez-Lima CV Updated Jan. 10, 2017

(Updated January 10, 2017) CURRICULUM VITAE Francisco Gonzalez-Lima 1. POSITION George I. Sanchez Centennial Professorship in Liberal Arts and Sciences Professor, Behavioral Neuroscience Area, Department of Psychology, College of Liberal Arts Professor, Division of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Pharmacy Professor, Institute for Neuroscience, College of Natural Sciences, Graduate Studies Program The University of Texas at Austin 2. ADDRESS The University of Texas at Austin, 108 E. Dean Keeton Stop A8000, Austin, TX 78712-1043, USA. Home: 5739 Merrywing Circle, Austin, TX 78730-1411, USA. Phone: Cell (512) 202-7375, Office (512) 475-8497, Fax (512) 910-8247. Email: [email protected] Webpage: http://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/psychology/faculty/fg 3. EDUCATION B.S., Biology, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 1976. B.A., Psychology, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 1977. Ph.D., Anatomy and Neurobiology, Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, School of Medicine, University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus, San Juan, Puerto Rico, USA, 1980. Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Behavioral Neuroscience, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany, 1983. 4. EXPERIENCE 4.1. Appointments Assistant Professor 1980-83, Associate Professor 1983-85, Department of Anatomy, Ponce School of Medicine, Ponce, Puerto Rico, USA. Assistant Professor 1986-90, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, College of Medicine, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA. Associate Professor 1991-96, Professor 1997-present, Head 1997-2001, Behavioral Neuroscience Area, George I. Sanchez Centennial Professorship in Liberal Arts and Sciences 2000-present, Director 2002-2011, Texas Consortium in Behavioral Neuroscience, Departments of Psychology, Pharmacology and Toxicology, Institute for Neuroscience, Imaging Research Center and Center for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA. -

CV Jessica Payne

JESSICA D. PAYNE, PH.D. Director, Sleep, Stress, and Memory (SAM) Laboratory Associate Professor of Psychology University of Notre Dame • Department of Psychology Corbett Hall, Room 466 • Notre Dame, IN 46556 Phone: 574-631-1636 • Fax: 574-631-8883 Email: [email protected] Revised 10/2020 PRIMARY ACADEMIC POSITION 2014-present Associate Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame 2019-2020 Andrew J. McKenna Family Collegiate Chair, University of Notre Dame 2011-2019 Nancy O’Neill Collegiate Chair, University of Notre Dame 2009-2014 Assistant Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame OTHER ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2012-2013 Visiting Professor, Boston College, Department of Psychology 2011-2012 H. Smith Richardson Jr. Fellow, Center for Creative Leadership, Greensboro, NC EDUCATION 2006-2009 Harvard University Postdoctoral Fellow, Psychology/Cognitive Neuroscience Advisors: Daniel Schacter and Robert Stickgold 2005-2006 Harvard Medical School, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Postdoctoral Fellow, Cognitive Neuroscience Advisor: Robert Stickgold 1-JP 1999-2005 University of Arizona, Ph.D., Psychology/Cognitive Neuroscience Advisor: Lynn Nadel 1997-1999 Mount Holyoke College, M.A., Experimental Psychology 1991-1995 University of San Diego, B.A., Psychology, magna cum laude RESEARCH GRANTS AND TRAINING FELLOWSHIPS Funded – National Science Foundation 09/01/2020-08/31/2024 Jessica D. Payne, P.I. (Elizabeth Kensinger, co-P.I.) National Science Foundation $899,876 Sleep and Selective Emotional Memory Consolidation from Young Adulthood through Middle Age: PSG and fMRI Investigations. This project examines whether sleep produces the same selective emotional memory benefits in middle- aged adults as younger adults, and whether the same sleep physiology and neural networks underlie this selective memory consolidation.