Midlife Chronological and Endocrinological Transitions In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Version

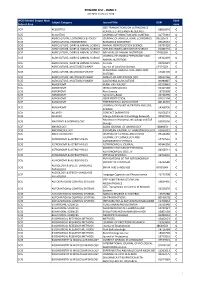

REWARD LIST ‐ RANK C JCR 2018 ‐CiteScore 2018 WOS Edition/ Scopus Main Rank Subject Category Journal Title ISSN Subject Area code IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON ULTRASONICS SCIE ACOUSTICS 08853010 C FERROELECTRICS AND FREQUENCY SCIE ACOUSTICS JOURNAL OF VIBRATION AND CONTROL 10775463 C SCIE AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS & POLICY JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS 0021857X C SCIE AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING BIOMASS & BIOENERGY 09619534 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE ANIMAL REPRODUCTION SCIENCE 03784320 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE APPLIED ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR SCIENCE 01681591 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE ARCHIVES OF ANIMAL NUTRITION 1745039X C JOURNAL OF ANIMAL PHYSIOLOGY AND SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE 09312439 C ANIMAL NUTRITION SCIE AGRICULTURE, DAIRY & ANIMAL SCIENCE Animals 20762615 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, MULTIDISCIPLINARY Journal of Land Use Science 1747423X C RENEWABLE AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SCIE AGRICULTURE, MULTIDISCIPLINARY 17421705 C SYSTEMS SCIE AGRICULTURE, MULTIDISCIPLINARY ANNALS OF APPLIED BIOLOGY 00034746 C SCIE AGRICULTURE, MULTIDISCIPLINARY CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURE 00080845 C SCIE AGRONOMY PLANT PATHOLOGY 00320862 C SCIE AGRONOMY IRRIGATION SCIENCE 03427188 C SCIE AGRONOMY Rice Science 16726308 C SCIE AGRONOMY Agronomy‐Basel 20734395 C SCIE AGRONOMY CROP PROTECTION 02612194 C SCIE AGRONOMY EXPERIMENTAL AGRICULTURE 00144797 C JOURNAL OF PLANT NUTRITION AND SOIL SCIE AGRONOMY 14368730 C SCIENCE SCIE ALLERGY CONTACT DERMATITIS 01051873 C SCIE ALLERGY Allergy Asthma & Immunology Research 20927355 C Advances -

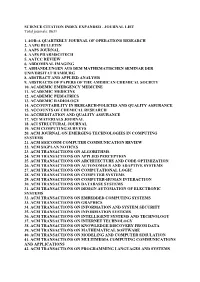

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Bioenergetic Abnormalities in Schizophrenia

Bioenergetic abnormalities in schizophrenia A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Neuroscience of the College of Medicine by Courtney René Sullivan B.S. University of Pittsburgh, 2013 Dissertation Committee: Mark Baccei, Ph.D. (chair) Robert McCullumsmith, M.D., Ph.D. (advisor) Michael Lieberman, Ph.D. Temugin Berta, Ph.D. Robert McNamara, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Schizophrenia is a devastating illness that affects over 2 million people in the U.S. and displays a wide range of psychotic symptoms, as well as cognitive deficits and profound negative symptoms that are often treatment resistant. Cognition is intimately related to synaptic function, which relies on the ability of cells to obtain adequate amounts of energy. Studies have shown that disrupting bioenergetic pathways affects working memory and other cognitive behaviors. Thus, investigating bioenergetic function in schizophrenia could provide important insights into treatments or prevention of cognitive disorders. There is accumulating evidence of bioenergetic dysfunction in chronic schizophrenia, including deficits in energy storage and usage in the brain. However, it is unknown if glycolytic pathways are disrupted in this illness. This dissertation employs a novel reverse translational approach to explore glycolytic pathways in schizophrenia, effectively combining human postmortem studies with bioinformatic analyses to identify possible treatment strategies, which we then examine in an animal model. To begin, we characterized a major pathway supplying energy to neurons (the lactate shuttle) in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in chronic schizophrenia. We found a significant decrease in the activity of two key glycolytic enzymes in schizophrenia (hexokinase, HXK and phosphofructokinase, PFK), suggesting a decrease in the capacity to generate bioenergetic intermediates through glycolysis in this illness. -

Jennifer I. Luebke 1 Curriculum Vitae Jennifer I. Luebke, Ph.D. Associate

Jennifer I. Luebke Curriculum Vitae Jennifer I. Luebke, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Anatomy & Neurobiology Associate Professor of Psychiatry Director, Laboratory of Cellular Neurobiology Boston University School of Medicine 85 East Newton Street, M949 Boston, Massachusetts 02118 Voice: 617-638-4930 Email: [email protected] Education and Employment History: 1980-1984: B.S. (Biology) Randolph-Macon College, Ashland, Virginia 1984-1986: Laboratory Technician (Laboratory of Cell Biology and Genetics, NIDDK) National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 1986-1990: Ph.D. Student (Anatomy & Neurobiology), Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts (Linda L. Wright, mentor) 1990-1992: Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Robert W. McCarley and Robert W. Greene mentors) 1992-1995: Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Physiology, Tufts University Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Kathleen Dunlap, mentor) 1995-2003: Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy & Neurobiology and Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 2004-Present: Associate Professor, Department of Anatomy & Neurobiology and Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 2010-Present: Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Neuroscience, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York Research Summary: Research is directed toward understanding alterations in the structure and function of individual cortical pyramidal cells in a rhesus monkey model of normal aging and in transgenic mouse models of neurodegenerative disease. Using whole-cell patch-clamp methods and ultra-high resolution confocal microscopy, Dr. Luebke has demonstrated marked alterations in action potential firing patterns (and underlying ionic currents), glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic response properties and detailed dendritic and spine architecture in cortical pyramidal cells both in normal aging and in mouse models of neurodegenerative disease. -

Biochemical Fossils of the Ancient Transition from Geoenergetics to Bioenergetics in Prokaryotic One Carbon Compound Metabolism☆

BBABIO-47248; No. of pages: 18; 4C: 4, 6, 7, 9 Biochimica et Biophysica Acta xxx (2014) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biochimica et Biophysica Acta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bbabio Biochemical fossils of the ancient transition from geoenergetics to bioenergetics in prokaryotic one carbon compound metabolism☆ Filipa L. Sousa, William F. Martin ⁎ Institute for Molecular Evolution,University of Düsseldorf, 40225 Düsseldorf, Germany article info abstract Article history: The deep dichotomy of archaea and bacteria is evident in many basic traits including ribosomal protein compo- Received 26 October 2013 sition, membrane lipid synthesis, cell wall constituents, and flagellar composition. Here we explore that deep di- Received in revised form 31 January 2014 chotomy further by examining the distribution of genes for the synthesis of the central carriers of one carbon Accepted 3 February 2014 units, tetrahydrofolate (H F) and tetrahydromethanopterin (H MPT), in bacteria and archaea. The enzymes un- Available online xxxx 4 4 derlying those distinct biosynthetic routes are broadly unrelated across the bacterial–archaeal divide, indicating Keywords: that the corresponding pathways arose independently. That deep divergence in one carbon metabolism is mir- Pterins rored in the structurally unrelated enzymes and different organic cofactors that methanogens (archaea) and Hydrothermal vents acetogens (bacteria) use to perform methyl synthesis in their H4F- and H4MPT-dependent versions, respectively, Origin of life of the acetyl-CoA pathway. By contrast, acetyl synthesis in the acetyl-CoA pathway — from a methyl group, CO2 Methanogens and reduced ferredoxin — is simpler, uniform and conserved across acetogens and methanogens, and involves Acetogens only transition metals as catalysts. -

Predicting Cognitive Decline: Genetic, Environmental and Lifestyle Risk Factors

Predicting Cognitive Decline: Genetic, Environmental and Lifestyle Risk Factors Shea J. Andrews April 2017 A thesis by compilation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University © Copyright by Shea John Frederick Andrews 2017 All Rights Reserved i Declaration This work was conducted from February 2013 to August 2016 at the Genome Diversity and Health Group, John Curtin School of Medical Research, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT. This thesis by compilation consists of five original publications describing the analyses I have performed during my candidature investigating the role of genetic, environmental and lifestyle risk factors in normal cognitive aging. All five publications have been published in Q1 ranked journals according to the SCImago Journal & Country Rankings in the fields of neurology, genetics, psychiatry and mental health, and geriatric and gerontology. My specific contribution to each manuscript is detailed in the subsequent pages in the form of a statement signed by the senior author of each publication. This document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Shea Andrews Canberra, Australia April 2017 ii Published Papers Andrews, SJ, Das, D., Anstey, KJ., Easteal, S. (2015). Interactive effect of APOE genotype and blood pressure on cognitive decline: The PATH through life project. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 44(4): 1087-98. DOI: 10.3233/JAD- 140630 For this publication, I designed and performed all statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. A slightly modified version of this paper is presented in Chapter 3. ____________________ Simon Easteal Senior Author April 2017 Andrews SJ, Das D, Cherbuin N, Anstey KJ, Easteal S. -

Brain Ageing in the New Millennium

Brain ageing in the new millennium Julian N. Trollor, Michael J. Valenzuela Objective: This paper examines the current literature pertaining to brain ageing. The objective of this review is to provide an overview of the effects of ageing on brain structure and function and to examine possible mediators of these changes. Methods: A MEDLINE search was conducted for each area of interest. A selective review was undertaken of relevant articles. Results: Although fundamental changes in fluid intellectual abilities occur with age, global cognitive decline is not a hallmark of the ageing process. Decline in fluid intellectual ability is paralleled by regionally specific age related changes apparent from both structural and functional neuroimaging studies. The histopathological mediators of these changes do not appear to be reduction in neuronal number, which, with the exception of selected hippo- campal regions, remain relatively stable across age. At the molecular level, several mech- anisms of age related change have been postulated. Such theoretical models await refinement and may eventually provide a basis for therapy designed to reduce effects of the ageing process. The role of possible protective factors such as ‘brain reserve’, neuro- protective agents and hormonal factors in modifying individual vulnerability to the ageing process has been the focus of a limited number of studies. Conclusion: Our understanding of the functional and structural changes associated with both healthy and pathological ageing is rapidly gaining in sophistication and complexity. An awareness of the fundamental biological substrates underpinning the ageing process will allow improved insights into vulnerability to neuropsychiatric disease associated with advancing age. Key words: brain ageing, cognition, dementia, neuroimaging. -

The Effects of Normal Aging on Myelin and Nerve Fibers: a Review∗

Journal of Neurocytology 31, 581–593 (2002) The effects of normal aging on myelin and nerve fibers: A review∗ ALAN PETERS Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Boston University School of Medicine, 715, Albany Street, Boston, MA 02118, USA [email protected] Received 7 January 2003; revised 4 March 2003; accepted 5 March 2003 Abstract It was believed that the cause of the cognitive decline exhibited by human and non-human primates during normal aging was a loss of cortical neurons. It is now known that significant numbers of cortical neurons are not lost and other bases for the cognitive decline have been sought. One contributing factor may be changes in nerve fibers. With age some myelin sheaths exhibit degenerative changes, such as the formation of splits containing electron dense cytoplasm, and the formation on myelin balloons. It is suggested that such degenerative changes lead to cognitive decline because they cause changes in conduction velocity, resulting in a disruption of the normal timing in neuronal circuits. Yet as degeneration occurs, other changes, such as the formation of redundant myelin and increasing thickness suggest of sheaths, suggest some myelin formation is continuing during aging. Another indication of this is that oligodendrocytes increase in number with age. In addition to the myelin changes, stereological studies have shown a loss of nerve fibers from the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres of humans, while other studies have shown a loss of nerve fibers from the optic nerves and anterior commissure in monkeys. It is likely that such nerve fiber loss also contributes to cognitive decline, because of the consequent decrease in connections between neurons. -

Technology and Aging in America (Part 14 Of

Appendix B The Cell Biology of Aging Introduction spans that seem to be “programmed” into them accord- ing to species. Mechanisms underlying this programmed The distinction between the effects of aging as a aging could involve an intrinsic genetic component of chronological process and diseases whose prevalence the tissues (24), and/or an extrinsic “neuroendocrine increase with advancing age remains blurred. Condi- pacemaker” (16,17). tions once thought to be inevitable companions of old The genetic version of the biological clock is bol- age are now known to in fact be pathological in origin stered by the observation that the survival time of and thus possibly treatable and preventable. One ex- tissues grafted (or transferred) from an older animal ample is senile dementia, no longer the mysterious fate into a younger one of the same species seems to de- of the very old, but often a clinical manifestation of pend on the age of the donor and is not influenced arteriosclerotic or biochemical brain disease. by the “younger” environment into which it has been Further research may elucidate the mechanisms introduced (24). Similarly, when nuclei from younger underlying aging and their possible connection to age- cells are transplanted into the cytoplasm of older cells, related diseases, leading to the development of medi- the recipients then live longer and regain the ability cal techniques that delay the onset and progression to replicate. These observations all suggest that a of symptoms. While it may not lead to actual exten- “clock” controlling aging does exist and may be located sion of the human life span, such knowledge could re- in the nucleus, possibly in the genetic material (24). -

Revolutionizing Neurodegenerative Disease Using Bioenergetic Nanotherapeutics to Improve Patients‘ Lives

CLENE INC. ANNUAL REPORT 2020 REPORT ANNUAL REVOLUTIONIZING NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASE USING BIOENERGETIC NANOTHERAPEUTICS TO IMPROVE PATIENTS‘ LIVES ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Breakthrough Needed for Patients Eective treatment of patients with neurodegenerative disorders requires a therapeutic breakthrough. The World Health Organization predicts diseases of neurodegeneration will become the second-most prevalent cause of death within the next 20 years1. Bioenergetic Opportunity Bioenergetic failure underlies the pathophysiology of many neurodegenerative diseases2. However, rescuing failing bioenergetic systems in these diseases has historically been extremely challenging3. Bioenergetic Nanotherapeutics Clene® is rapidly advancing a pipeline of bioenergetic nanotherapeutics, the first of those is CNM-Au8, designed to enhance naturally occurring cellular metabolism with the goal of reversing neurodegeneration. This new class of drugs called bioenergetic nanocatalysts has been created to accelerate neurorepair, improve neuroprotection, and enhance remyelination4. Innovative Platform The innovative platform is an electrochemistry approach to growing clean-surfaced, metallic nanocrystal therapeutics. The nanotherapeutic CNM-Au8 is designed to optimize cellular health and repair through energy enhancing bioenergetic catalysis. Using pure, clean-surfaced gold nanocrystals, we are able to amplify healthy, intracellular reactions necessary for cells to function and defend CLENE themselves from disease4. INNOVATE PROTECT REPAIR BIOENERGETIC NANOTHERAPEUTICS CNM-Au8 Clene Team Clene carefully engineered its lead drug Behind every innovative platform is a candidate, CNM-Au8, a bioenergetic team of inventive minds. Clene nanocatalyst which enhances critical enlisted a leadership team of intracellular bioenergetic reactions seasoned industry veterans united by necessary for repairing and reversing their appetite for innovation and neuronal damage. Orally administered, committed to advancing the CNM-Au8 has demonstrated safety in Phase company’s pipeline rapidly. -

Estrogen: a Master Regulator of Bioenergetic Systems in the Brain and Body ⇑ Jamaica R

Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 35 (2014) 8–30 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yfrne Review Estrogen: A master regulator of bioenergetic systems in the brain and body ⇑ Jamaica R. Rettberg a, Jia Yao b, Roberta Diaz Brinton a,b,c, a Neuroscience Department, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033, United States b Department of Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033, United States c Department of Neurology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033, United States article info abstract Article history: Estrogen is a fundamental regulator of the metabolic system of the female brain and body. Within the Available online 29 August 2013 brain, estrogen regulates glucose transport, aerobic glycolysis, and mitochondrial function to generate ATP. In the body, estrogen protects against adiposity, insulin resistance, and type II diabetes, and regu- Keywords: lates energy intake and expenditure. During menopause, decline in circulating estrogen is coincident with Adipokine decline in brain bioenergetics and shift towards a metabolically compromised phenotype. Compensatory Adipose tissue bioenergetic adaptations, or lack thereof, to estrogen loss could determine risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s Aging disease. Estrogen coordinates brain and body metabolism, such that peripheral metabolic state can indi- Alzheimer’s disease cate bioenergetic status of the brain. By generating biomarker profiles that encompass peripheral meta- Biomarker Insulin bolic changes occurring with menopause, individual risk profiles for decreased brain bioenergetics and Menopause cognitive decline can be created. Biomarker profiles could identify women at risk while also serving as Metabolism indicators of efficacy of hormone therapy or other preventative interventions. -

Integrated Transcriptomic and Neuroimaging Brain Model Decodes

RESEARCH ARTICLE Integrated transcriptomic and neuroimaging brain model decodes biological mechanisms in aging and Alzheimer’s disease Quadri Adewale1,2,3, Ahmed F Khan1,2,3, Felix Carbonell4, Yasser Iturria-Medina1,2,3*, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative† 1Neurology and Neurosurgery Department, Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Canada; 2McConnell Brain Imaging Centre, Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Canada; 3Ludmer Centre for Neuroinformatics and Mental Health, McGill University, Montreal, Canada; *For correspondence: 4Biospective Inc, Montreal, Canada [email protected] †Data used in preparation of this article were partly obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Abstract Both healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are characterized by concurrent Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) alterations in several biological factors. However, generative brain models of aging and AD are database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As limited in incorporating the measures of these biological factors at different spatial resolutions. such, the investigators within the Here, we propose a personalized bottom-up spatiotemporal brain model that accounts for the ADNI contributed to the design direct interplay between hundreds of RNA transcripts and multiple macroscopic neuroimaging and implementation of ADNI modalities (PET, MRI). In normal elderly and AD participants, the model identifies top genes and/or provided data but did not modulating tau and amyloid-b burdens, vascular flow, glucose metabolism, functional activity, and participate in analysis or writing atrophy to drive cognitive decline. The results also revealed that AD and healthy aging share of this report. A complete listing specific biological mechanisms, even though AD is a separate entity with considerably more altered of ADNI investigators can be pathways.