Papa Don't Preach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Premiere

World Premiere FILMOGRAPHY A Message from Oliver Stone has directed: “W.” (‘08), “World Trade Center” (‘06), “Alexander” (‘04), “Any Given Sunday” (‘99), “U–Turn” (‘97), “Nixon” (‘95), “Natural Born Killers” (‘94), Oliver Stone “Heaven and Earth” (‘93), “JFK” (‘91), “The Doors” (‘91), “Born On The Fourth Of July” (‘89), I’ve been fortunate to be able “Talk Radio” (‘88), “Wall Street” (‘87), “Platoon” (‘86), “Salvador” (‘86), “The Hand” (‘81) to make several films about North and “Seizure” (‘73). He’s written or co–written all of the above, with the exception of America’s neglected “backyard” “U–Turn”, “World Trade Center” and “W.”. –– Central and South America. He’s also written or co–written: “Midnight Express” (‘78), “Scarface” (‘83), The low budget, independently “Conan The Barbarian” (‘82), “Year Of The Dragon” (‘85), “Evita” (‘96), and shot SALVADOR, about the U.S. “8 Million Ways To Die” (’86). involvement with the death squads of El Salvador, and starring James He’s directed 3 documentaries –– “Looking for Fidel” (‘04), “Comandante” (‘03), Woods in an Oscar–nominated “Persona Non Grata” (‘03). performance, was released in 1986; this was followed by COMANDANTE He’s produced or co–produced: “The People vs. Larry Flynt” (‘96), in 2003, and LOOKING FOR FIDEL in “The Joy Luck Club” (‘93), “Reversal of Fortune” (‘90), “Savior” (‘98), 2004, both of these documentaries “Freeway” (‘96),“South Central” (‘98), “Zebrahead” (‘92), “Blue Steel” (‘90), exploring Fidel Castro in one–on–one and the ABC mini–series “Wild Palms” (‘93). An Emmy was given to him and his interviews. Each of these films has struggled to be distributed in North America. -

Top 30 Films

March 2013 Top 30 Films By Eddie Ivermee Top 30 films as chosen by me, they may not be perfect or to everyone’s taste. Like all good art however they inspire debate. Why Do I Love Movies? Eddie Ivermee For that feeling you get when the lights get dim in the cinema Because of getting to see Heath Ledger on the big screen for the final time in The Dark Knight Because of Quentin Tarentino’s knack for rip roaring dialogue Because of the invention of the steadicam For saving me from the drudgery of nightly weekly TV sessions Because of Malik’s ability to make life seem more beautiful than it really is Because of Brando and Pacino together in The Godfather Because of the amazing combination of music and image, e.g. music in Jaws Because of the invention of other worlds, see Avatar, Star Wars, Alien etc. For making us laugh, cry, sad, happy, scared all in equal measure. For the ending of the Shawshank Redemption For allowing Jim Carey lose during the 1990’s For arranging a coffee date on screen of De Niro an Pacino For allowing Righteous Kill to go straight to DVD so I could turn it off For taking me back in time with classics like Psycho, Wizard of Oz ect For making dreams become reality see E.T, The Goonies, Spiderman, Superman For allowing Brad Pitt, Michael Fassbender, Tom Hardy and Joesph Gordon Levitt ply their trade on screen for our amusement. Because of making people Die Hard as Rambo strikes with a Lethal Weapon because he is a Predator who is also Rocky. -

HH Available Entries.Pages

Greetings! If Hollywood Heroines: The Most Influential Women in Film History sounds like a project you would like be involved with, whether on a small or large-scale level, I would love to have you on-board! Please look at the list of names below and send your top 3 choices in descending order to [email protected]. If you’re interested in writing more than one entry, please send me your top 5 choices. You’ll notice there are several women who will have a “D," “P," “W,” and/or “A" following their name which signals that they rightfully belong to more than one category. Due to the organization of the book, names have been placed in categories for which they have been most formally recognized, however, all their roles should be addressed in their individual entry. Each entry is brief, 1000 words (approximately 4 double-spaced pages) unless otherwise noted with an asterisk. Contributors receive full credit for any entry they write. Deadlines will be assigned throughout November and early December 2017. Please let me know if you have any questions and I’m excited to begin working with you! Sincerely, Laura Bauer Laura L. S. Bauer l 310.600.3610 Film Studies Editor, Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal Ph.D. Program l English Department l Claremont Graduate University Cross-reference Key ENTRIES STILL AVAILABLE Screenwriter - W Director - D as of 9/8/17 Producer - P Actor - A DIRECTORS Lois Weber (P, W, A) *1500 Major early Hollywood female director-screenwriter Penny Marshall (P, A) Big, A League of Their Own, Renaissance Man Martha -

Available from TCG Books: I’Ll Eat You Last and Peter and Alice by John Logan

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dafina McMillan May 21, 2013 [email protected] | 212-609-5955 Available from TCG Books: I’ll Eat You Last and Peter and Alice by John Logan NEW YORK, NY – Theatre Communications Group (TCG) is pleased to announce the availability of two new plays by John Logan: I’ll Eat You Last: A Chat with Sue Mengers and Peter and Alice, both published by Oberon Books (London). The three-time Oscar-nominated screenwriter of such films as Skyfall and Hugo returns with two new plays on Broadway and in London’s West End, respectively. I’ll Eat You Last is a one-woman show about legendary Hollywood super-agent Sue Mengers, whose clients included Barbra Streisand, Cher, Gene Hackman and Mike Nichols. Currently on Broadway, starring Bette Midler, I’ll Eat You Last is nominated for the 2013 Drama League awards for Outstanding Production of a Broadway or Off-Broadway Play. Based on the real individuals that inspired J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan and Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, Peter and Alice tells the story of when Alice Liddell Hargreaves met Peter Llewelyn Davies at the opening of a Lewis Carroll exhibition in 1932. Currently playing to acclaim in the West End, Judi Dench stars as Alice and Ben Whishaw as Peter in this new play where enchantment and reality collide. “A delectable soufflé of a solo show… It’s a heady sensation, thanks to the buoyant, witty writing of Mr. Logan… Tangy and funny.” — New York Times on I’ll Eat You Last “A haunting play that sounds profound notes of loss and grief.. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI' The Spectacle of Gender: Representations of Women in British and American Cinema of the Nineteen-Sixties By Nancy McGuire Roche A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University May 2011 UMI Number: 3464539 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3464539 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Spectacle of Gender: Representations of Women in British and American Cinema of the Nineteen-Sixties Nancy McGuire Roche Approved: Dr. William Brantley, Committees Chair IVZUs^ Dr. Angela Hague, Read Dr. Linda Badley, Reader C>0 pM„«i ffS ^ <!LHaAyy Dr. David Lavery, Reader <*"*%HH*. a*v. Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department ;jtorihQfcy Dr. Michael D1. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies Nancy McGuire Roche Approved: vW ^, &v\ DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the women of my family: my mother Mary and my aunt Mae Belle, twins who were not only "Rosie the Riveters," but also school teachers for four decades. These strong-willed Kentucky women have nurtured me through all my educational endeavors, and especially for this degree they offered love, money, and fierce support. -

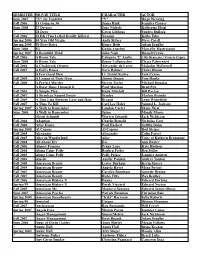

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Any Given Sunday

Wettbewerb/IFB 2000 ANY GIVEN SUNDAY AN JEDEM VERDAMMTEN SONNTAG ANY GIVEN SUNDAY Regie: Oliver Stone USA 1999 Darsteller Tony D’Amato Al Pacino Länge 160 Min. Christina Pagniacci Cameron Diaz Format 35 mm, Jack „Cap“ Rooney Dennis Quaid Cinemascope Dr.Harvey Mandrake James Woods Farbe Willie Beamen Jamie Foxx Julian Washington LL Cool J Stabliste Dr.Ollie Powers Matthew Modine Buch John Logan AFFA-Präsident Charlton Heston Oliver Stone,nach Margaret Pagniacci Ann-Margret einer Idee von Nick Crozier Aaron Eckhart Daniel Pyne und Jack Rose John McGinley John Logan Montezuma Monroe Jim Brown Kamera Salvatore Totino Luther „Shark“ Lavay Lawrence Taylor Kameraführung Keith Smith Jimmy Sanderson Bill Bellamy Kameraassistenz Steve Meizler Patrick „Madman“ Schnitt Tom Nordberg Kelly Andrew Bryniarski Keith Salmon Vanessa Struthers Lela Rochon Stuart Waks Cindy Rooney Lauren Holly Stuart Levy Mandy Murphy Elizabeth Berkley Ton Kevin Cerchiai Jamie Foxx, Al Pacino Christinas Berater James Karen Mischung Peter Devlin Gianni Russo Musik Robbie Robertson Willies Agent Duane Martin Paul Kelly AN JEDEM VERDAMMTEN SONNTAG Bürgermeister Smalls Clifton Davis Richard Horowitz Vier Jahre ist es her,daß die Miami Sharks die Football-Meisterschaft gewon- Fernsehkommentator Oliver Stone Production Design Victor Kempster nen haben, inwischen sieht die Lage des von Tony D’Amato trainierten Ausstattung Stella Vaccaro Teams recht finster aus: Nach einer Niederlagenserie bleiben die Zuschauer Kostüm Mary Zophres aus, der alternde Star-Quarterback „Cap“ Rooney und auch sein Ersatzmann Maske John Blake Regieassistenz George Parra „J Man“ Washington fallen verletzt für Wochen aus. Die Besitzerin des Clubs, Richard Patrick Christina Pagniacci, ist drauf und dran, neue Spieler zu verpflichten, da Produktionsltg. -

Boulder International Film Festival

FilmBoulder Festival International movesi celebrating the bold spirit >> welcome Welcome to the 7th Annual Boulder International Film Festival, a non-profit community festival staffed almost entirely by energized volunteers and voted “one of the coolest film festivals in the world” byMovieMaker magazine. That’s because of you, the huge, film-hip, Boulder audiences who show up by the thousands to be a part of the big world of ideas and passions that are light- years beyond the normal muck of American mass corporate media. This year’s BIFF will honor one of the greatest, most thought-provoking film directors of our time—three-time Oscar winner Oliver Stone (Midnight Express, Platoon, Born on the Fourth of July). Mr. Stone will receive BIFF’s Master of Cinema Award and sit down for an in-depth interview and retrospective of his films at the Closing Night ceremonies on Sunday night. Last year, BIFF welcomed Alec Baldwin just weeks before he co-hosted the 2010 Academy Awards. Continuing that tradition, we are excited to present voteWHAT ROCKS YOU AT BIFF? 2011’s Oscar co-host, movie mega-star James Franco (the Spider-Man trilogy, Get a ballot on your way in to Milk, Howl, 127 Hours) for an evening retrospective of his films. - each program. Take 10 sec BIFF is happy to welcome back Oscar-nominated producer Don Hahn (Beauty onds to vote. Hand it back on and the Beast, The Lion King) who will present his touching new film,Hand your way out. Easy! Bribes not Held. Mr. Hahn will also be a moderator of honor for a reprise of one of the accepted. -

MÖTLEY CRÜE Announces the FINAL TOUR Presented by Dodge

MÖTLEY CRÜE Announces THE FINAL TOUR Presented by Dodge Band is first-ever to sign binding “Cessation of Touring” agreement to prevent future, unauthorized touring Last Chance To Ever See The Band Perform Live TWEET IT: #RIPMotleyCrue - @MotleyCrue announces #TheFinalTour, Country tribute album, "The Dirt" movie & more! Full details at motley.com Los Angeles, CA (January 28, 2014) – After more than three decades together, iconic rock ‘n roll band MÖTLEY CRÜE announced today their Final Tour and the band’s ultimate retirement. The announcement was solidified when the band signed a formal Cessation Of Touring Agreement, effective at the end of 2015, in front of global media in Los Angeles today. Celebrating the announcement of this Final Tour, the 1 band will perform on ABC’s Jimmy Kimmel Live TONIGHT and will appear on CBS This Morning TOMORROW MORNING. With over 80 million albums sold, MÖTLEY CRÜE has sold out countless tours across the globe and spawned more than 2,500 MÖTLEY CRÜE branded items sold in over 30 countries. MÖTLEY CRÜE has proven they know how to make a lasting impression and this tour will be no different; Fans can expect to hear the catalogue of their chart- topping hits and look forward to mind-blowing, unparalleled live production. “When it comes to putting together a new show we always push the envelope and that’s part of Motley Crue’s legacy,” explains Nikki Sixx (bass). “As far as letting on to what we’re doing, that would be like finding out what you’re getting for Christmas before you open the presents. -

VOCAL PREPARATION for the HIGH SCHOOL MALE (Preparing the High School Male Soloist for Contest/Audition - a Choral Director’S Guide)

VOCAL PREPARATION FOR THE HIGH SCHOOL MALE (Preparing the High School Male Soloist for Contest/Audition - A Choral Director’s Guide) D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Todd Edward Ranney, B.M., B.M., M.M., M.M., A.D. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 D.M.A. Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Dr. Robin Rice, Advisor Dr. Hilary Apfelstadt Dr. Akos Seress Dr. Wayne Redenbarger _________________________ Copyright by Todd E. Ranney 2009 Abstract The development of the high school male voice takes tremendous knowledge and care. This document outlines an approach to vocal instruction for adolescent male changed voices for use by voice teachers, choral directors, and students. For practical purposes, the author uses both technical and non-technical language in order to communicate to the aspiring young singer and teachers and directors. The document outlines topics and teaching strategies for tenors, baritones, and basses encompassing pedagogy, repertoire and performance practices. Also included in the document are several appendices that list repertoire such as that recommended by the Ohio Music Educators Association (OMEA), selections that are appropriate for contest and audition material. ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my deepest thanks and appreciation to Dr. Robin Rice for his wealth of counsel, guidance and friendship during my stay at OSU. Also my sincerest gratitude goes to Dr. Patrick Woliver, Dr. Hilary Apfelstadt, and Dr. Wayne Redenbarger for serving on my committee and providing me with valuable information throughout my educational process. -

Lights! Camera! Action! Lights! Camera! Action! Southern States Efforts to Attract Filmmakers’ Business by Sujit M

The Council of State Governments Sharing capitol ideas Southern Legislative Conference Lights! Camera! Action! Action! Camera! Lights! Southern States Efforts to Attract Filmmakers’ Business By Sujit M. CanagaRetna, Senior Fiscal Analyst Southern Legislative Conference JUNE 2007 Southern States Efforts to Attract Filmmakers’ Business Filmmakers’ Attract to Efforts States Southern Introduction The motion picture industry—symbolized by of permanent movie theaters and the formation of a Hollywood—remains one of the most identified global number of ancillary activities related to the industry. associations with America, a phenomenon that has prevailed for almost a century now.* Ever since the By the late 1910s and early 1920s, most American famed American inventor Thomas Alva Edison and film production had moved to Hollywood, California, his British assistant William Kennedy Laurie Dickson although some movies continued to be produced in New first developed the Kinetophonograph, a device that Jersey and in Queens, New York. The relocation was synchronized film projection with sound from a the result of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce phonograph record in 1891, America’s influence in the proffering a range of incentives to lure filmmakers to development and advancement of this industry to its the West Coast— Hollywood specifically—including current level has been preeminent.1 Further, progress lower labor costs, relatively inexpensive and abundant in these endeavors led to the 1894 screening of the land for studio construction, a variety of landscapes first commercially exhibited movie as we know them for every type of film, along with the guarantee of today in New York City and, in 1895, Edison exhibited extended periods of sunshine, a vital commodity before hand-colored movies at the Cotton States Exhibition the dawn of indoor studios and artificial lighting. -

Oliver Stone Sur Le Net : Un Cinéaste Américain

Document generated on 09/27/2021 8:33 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Oliver Stone sur le Net Un cinéaste américain Carl Rodrigue Number 234, November–December 2004 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/48039ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rodrigue, C. (2004). Oliver Stone sur le Net : un cinéaste américain. Séquences, (234), 16–17. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2004 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ -i» LES TOILES DU CINEMA Oliver Stone sur le Net UN CINÉASTE AMÉRICAIN « Le pire cauchemar que j'ai eu à propos du Vietnam fut celui où j'ai rêvé que je devais y retourner. » Oliver Stone http://membres.lycos.fr/ngoueset ™ Ka ertainement le douzaine de fois. Je voulais le montrer visionnant le film avant de plus américain lancer l'attaque sur le Cambodge. Mais ce fils de pute de George 1 des cinéastes C. Scott m'a empêché de tourner cette scène que j'avais écrite en 1 • •• c américains, Oliver me refusant le droit d'utiliser son image.