The Making of the Modern Marine Corps Through Public Relations, 1898-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Bicentennial Speeches (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 2, folder “Bicentennial Speeches (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 2 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON June 28, 1976 MEMORANDUM FOR ROBERT ORBEN VIA: GWEN ANDERSON FROM: CHARLES MC CALL SUBJECT: PRE-ADVANCE REPORT ON THE PRESIDENT'S ADDRESS AT THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES Attached is some background information regarding the speech the President will make on July 2, 1976 at the National Archives. ***************************************************************** TAB A The Event and the Site TAB B Statement by President Truman dedicating the Shrine for the Delcaration, Constitution, and Bill of Rights, December 15, 1952. r' / ' ' ' • THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON June 28, 1976 MEMORANDUM FOR BOB ORBEN VIA: GWEN ANDERSON FROM: CHARLES MC CALL SUBJECT: NATIONAL ARCHIVES ADDENDUM Since the pre-advance visit to the National Archives, the arrangements have been changed so that the principal speakers will make their addresses inside the building . -

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

Thesis-1972D-C289o.Pdf (5.212Mb)

OKLAHOMA'S UNITED STATES HOUSE DELEGATION AND PROGRESSIVISM, 1901-1917 By GEORGE O. CARNE~ // . Bachelor of Arts Central Missouri State College Warrensburg, Missouri 1964 Master of Arts Central Missouri State College Warrensburg, Missouri 1965 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1972 OKLAHOMA STATE UNiVERSITY LIBRARY MAY 30 1973 ::.a-:r...... ... ~·· .. , .• ··~.• .. ,..,,.·· ,,.,., OKLAHOMA'S UNITED STATES HOUSE DELEGATION AND PROGRESSIVIS~, 1901-1917 Thesis Approved: Oean of the Graduate College PREFACE This dissertation is a study for a single state, Oklahoma, and is designed to test the prevailing Mowry-Chandler-Hofstadter thesis concerning progressivism. The "progressive profile" as developed in the Mowry-Chandler-Hofstadter thesis characterizes the progressive as one who possessed distinctive social, economic, and political qualities that distinguished him from the non-progressive. In 1965 in a political history seminar at Central Missouri State College, Warrensburg, Missouri, I tested the above model by using a single United States House representative from the state of Missouri. When I came to the Oklahoma State University in 1967, I decided to expand my test of this model by examining the thirteen representatives from Oklahoma during the years 1901 through 1917. In testing the thesis for Oklahoma, I investigated the social, economic, and political characteristics of the members whom Oklahoma sent to the United States House of Representatives during those years, and scrutinized the role they played in the formulation of domestic policy. In addition, a geographical analysis of the various Congressional districts suggested the effects the characteristics of the constituents might have on the representatives. -

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

Transforming America's Military

00 Covers 10/11/02 4:21 PM Page 1 TRANSFORMING MILITARY TRANSFORMING AMERICA’S AMERICA’S MILITARY edited and with an introduction by Hans Binnendijk, with TRANSFORMING contributions from: Charles L. Barry • Paul K. Davis AME R I CA’S Michèle A. Flournoy • Norman Friedman Jacques S. Gansler • Thomas C. Hone Richard L. Kugler • Douglas A. Macgregor MI LITARY Thomas L. McNaugher • Mark L. Montroll Bruce R. Nardulli • Paul M. Needham David A. Ochmanek • William D. O’Neil Stephen P. Randolph • Richard D. Sokolsky Sam J. Tangredi • Bing West Peter A. Wilson edited by Hans Binnendijk BINNENDIJK Center for Technology and National Security Policy The National Defense University (NDU) established the Center for Technology and National Security Policy in June 2001 to study the implications of technological innovation for U.S. national security policy and military planning. The center combines scientific and technical assessments with analyses of current strategic and defense policy issues. Its major initial areas of focus include: (1) technologies and concepts that encourage and/or enable the transformation of the Armed Forces, (2) developments by defense laboratories, (3) investments in research, development, and acquisition and improvements to their processes, (4) relationships among the Department of Defense, the industrial sector, and academe, and (5) social science techniques that enhance the detection and prevention of conflict. The staff is led by two senior analysts who hold the Roosevelt Chair of National Security Policy and the A PUBLICATION OF THE Edison Chair of Science and Technology and who can call on the expertise of the NDU community and CENTER FOR TECHNOLOGY AND NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY colleagues at institutions nationwide. -

Detroit Blue Book

DAU'S DETROIT BLUE BOOK AND LADIES' ADDRESS BOOK ELITE FAMILY DIRECTORY OFFICIAL CLUB LISTS PUBLISHED ANNUALLY EDITION FOR 1 905 This book is the legitimate successor to the original Detroit Blue Book, published by the Free Press Publishing Company in 188s_. The public are warned against spurious imitations of this publication, and our patrons will favor us by bringing to our notice any misrepresentai.lcns by canvassers, etc. All contracts and subscriptions should bear our name. DAU PUBLISHING COMPANY, MOFFAT BLOCK, DETROIT, MICH. HEAD OFFICE, 54 WEST 22D STREET, NEW YORK COPVftlGHT 1904 8Y DAU PUBLISHING CO. THIS BOOK IS THE PROPE.RTY OF - R. --------------------- :QRRECT 4'v for Social Occasions, Recep - tion and At-Home C a rd s , NGRAVING Calling C a r d s, Wedding lnvitatic,ns ~ ~ ~ EVERY FEATURE OF SOCIAL ENGRAVING CORRECT IN EVERY LITTLE DETAIL ~en you order engraving and cards you -want the~ right. There'll be no little defects in the w-orh. done by us. All orders executed -with promptness and despatch. BOOB. AND STA"FIONERY DEPT., SECOND FLOOR ~HE J. L. HUDSON CO. r.', . :;ARD ·pARTIES • • • WHITE TABLES t\..ND CHAIRS ~ ~ FOR RENT~~~ ARTISTIC AND ELEGANT J:4""URNITURE l. R. LEONARD FURNirrURE CO. mcoRFORATED UNDER THE LAWS OF MICHIGAN Michigan Conservator.y of Music Washington Ave. and Park St. ALBERTO JONAS, Director Has acquired National Fame as the representative musical institution of Michigan, and one of the foremost, largest and most exclusive Conservatories in America. A faculty of forty-five eminent instructors, including world renowned artists. 'l'he very best instruction given in piano. -

MGUTTAIY HEADQUARTERS Raleigh, Mr

Services for Le Jeune Activity of U-Boats D. C. Executive KiHd Scheduled Tomorrow; Reported Slackening By Shotgun Blast in Burial in Arlington In Mediterranean Duck Blind Accident*« "* Included Among Honorary 'Good Knock' Handed to F. C. Victim Pallbearers Are Daniels, Ferber, 49, Pershing and Marshall Enemy's Subs, Says Of Odd Hunting Mishap Admiral Cunningham As Wife Sits Nearby* , B? the Associated Press. ■ i The War By the Associated Press. Department announced Francis C. Ferber, 49, >, vice last that ALLIED FORCE night Josephus Daniels, president of Southern former Secretary of the Navy; Gen. HEADQUARTERSIN NORTH AFRICA, Nov. Wholesalers,1519 L street N.W., was John J. Pershing and Gen. George C. 21.—During the past 48 hours killed in a Maryland duck blind Marshall, chief of staff, have there has been a “definite yesterday afternoon when a acceptedinvitations to act as honorary slackeningof U-boat activity in the fell and discharged into shotgun * pallbearers at services * tomorrow for Western Mediterranean, Admiral; his head and neck. Lt. Gen. John A. Le Jeune, retired, Mr. Ferber was in a blind about former commandant of the Marine Sir Andrew Brown Cunningham, Corps. commander of the naval forces 10 feet off shore of Brewer's Creek at Sherwood Forest, Md., where ha Gen. Le Jeune. who died Friday in in the North African operations, has a summer His wife Baltimore, will be buried with full cottage. declared military honors in Arlington today. was with him at the time. Cemetery. He said that the Royal Navy and Dr. John M. Claffey, Anne Lt. Gen. -

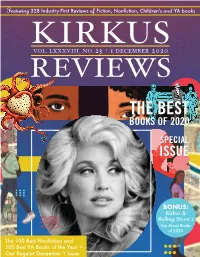

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb. -

University of Massachusetts Boston Coininenceinent 1 9 9 8

University of Massachusetts Boston Coininenceinent 1 9 9 8 Saturday, May 30 at 11:00 am After the Main Ceremony Diploma presentation ceremonies for individual UMass Boston colleges will be held after the main ceremony. Some graduates will leave the main hall and move to other locations in the Expo Center, followed by their families and friends. Other graduates, families, and friends will remain where they are. To make the Commencement experience as pleasant as possible for everyone involved, we ask all graduates and their guests to follow the instructions below. Information for Graduating Students College of Arts and Sciences graduates, including recipients of graduate degrees, should remain seated after the main ceremony. Graduates of the McCormack Institute should also remain seated. The diploma presentation ceremony for these graduates will be held in the main hall. All other graduates, including recipients of graduate degrees, will be asked to leave in groups, college by college. Graduates should wait until their college is announced. They should then march down the main aisle, following color coded banners for their colleges, to the locations of their ceremonies. The color codes are: College of Management Dark blue College of Public and Community Service Red Graduate College of Education Light blue College of Nursing and Human Performance Peach and Fitness Program Information for Guests As courtesy to the graduating students, we ask family members and friends to remain in their seats until all the graduates have been escorted to their indi vidual college ceremony locations. Guests of College of Arts and Sciences graduates, including recipients of graduate degrees, should remain seated after the main ceremony. -

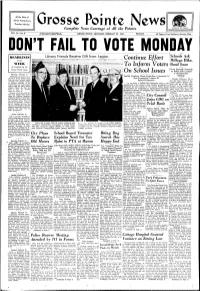

Effort Isc~Ooisa~K ...To Inform Voters

'\ • • . .. '. "4. 1. .-.~ ,~., '. ~. All the News of • All the Pointes Every Thursday Morning rosse PoInte ews Complete News Coverage of All the Pointes Home of the News Entered as Second Class MaUer at VOL. 2?- No.8 the Post OEftce at Detroit, Mlchlgan GROSSE ~c::>~~_T_E_,_~ICH IGAN_, _F_EB_R_U_A_R_Y_~~~1_1_968------'foc-.oo-:.-~r-c~-~~-r -----4-0-P-a-g-e-s -~Q T-w-o-S-ec-t-io-n-s --S-e-c-tj-,.,--n -0-n-8- , --------------------------_._--------~------ I. I ----------------------------, ---- ~I -- II 1~i\I)I~INES Library Friends Receive Gift from Continue Effort ISc~ooIs A~k of the i MIllage HIke, \\TI~I~K ....To Inform Voters !Bond Issue As Compiled by the Grosse Pointe New.~ Three Separate Proposals ".r:~';OnSchool Issues on Ballot; Polls located in All Elementary Thu:sday, Februar)' 15 ": Possible Questions About Proposition 3 Answered In Buildings PRESSURE IS R1SI~G for a I , call.up of group reserve units! t Quiz Prepared By Trustees Of Board Of Educat'lon l\Ionday, February 26, is from the Army National Guard I j the day that voters of the to bolster the strategic reStlrve r of divisions available in the ..i In an effort to inform the community fully on the Grosse Pointe School Dis- United Stctes for swift deploy' "I background to the special school election scheduled for trict wil! go to' the polls ment around the world. Senior Fe'oruary 26, the trustees of the Grosoe Pointe Board located In the public ele- military oCficers say they be. of ~ducation are conducting an informational campaign mentary schools s e r v i n g Iieve al least one division deSIgned to answer aII questions that citizens may have their areas, and ballot on should be called up. -

THE UNITED STATES MARINES Tn

MARINECORPS HISTORICAT REFERENCE PAMPHLET THEUNITED STATES MARINES tN |CELAND,tg4t -t942 @ HtsToRtcALDtvtstoN HEADQUARTERS,U.S. MARINE CORPS WASHINGTON,D.C. t970 .t .c J o o B tr lr : J1 \o c) c) OE c. p2 qJ9 r, c r-.1 o -ed uo s Z:J o0) TIIE UNITED STATES MARINES ]N ICEI]AND,].941-1942 Lieutenant Col-onel Kenneth ,f. Clifford. USMCR JloaEor Historical Division Headquarters, U. S. Marine Corps Washington, D. c" 20380 197 0 DEPARTITlENTOF THE NAVY HEAOOUARTERSUNITED STATES MAR]'!E CORPS WASHTNGTON,D. C 20340 PREFACE The material in tlris pamphl et has been extracted from chapter 4 of Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal---Historv of the United States Marine corps Operations in World War If, Volume I by Lieutenant Colonel Frank O. Hough, USMCR, Major Verle E, Ludwig, USMCand Mr. Henry I. Stiaw. .Tr. In addition, a bibliography and appendix has been added. Ttii s pamphlet supersedes Marine Corps Historical Reference Series pamphlet number 34. The United states Marines Ln Iceland, L94L-1942, published and l-ast reviewed in 1962t by the Historical Branch, G-3 Division. Headquarters, U. s. Marine corps. The Marine defense of lcel,and is one of the many actions categorized by Admiral sanuel Eliot Morison as rrshort of war operations." It is an important story and this pamphlet is published for the information of tttose interested in this h:r+i^,r'lrr ar2 ih ^!rr lic+^.".- --rY. nrr, Q/ z i'{//42" 't'Yt" w. J. v4N RYZrN ' LjeuLenani Ceneral, U.S. Morine CoLps Chjef oF SLaff, HeadcLu€rEe!s, Marine Corps Reviewed and Approved: 29 J arLrrary 1970 aaa TABI,E OF CONTENTS Extracts fron Chapter 4' volune 1, Pearl Harbor to cuaalal-canal"---Historv of U. -

Us Marines, Manhood, and American Culture, 1914-1924

THE GLOBE AND ANCHOR MEN: U.S. MARINES, MANHOOD, AND AMERICAN CULTURE, 1914-1924 by MARK RYLAND FOLSE ANDREW J. HUEBNER, COMMITTEE CHAIR DANIEL RICHES LISA DORR JOHN BEELER BETH BAILEY A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2018 Copyright Mark Ryland Folse 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that between 1914 and 1924, U.S. Marines made manhood central to the communication of their image and culture, a strategy that underpinned the Corps’ effort to attract recruits from society and acquire funding from Congress. White manhood informed much of the Marines’ collective identity, which they believed set them apart from the other services. Interest in World War I, the campaigns in Hispaniola, and the development of amphibious warfare doctrine have made the Marine Corps during this period the focus of traditional military history. These histories often neglect a vital component of the Marine historical narrative: the ways Marines used masculinity and race to form positive connections with American society. For the Great War-era Marine Corps, those connections came from their claims to make good men out of America’s white youngsters. This project, therefore, fits with and expands the broader scholarly movement to put matters of race and gender at the center of military history. It was along the lines of manhood that Marines were judged by society. In France, Marines came to represent all that was good and strong in American men.