A Bove the Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Bicentennial Speeches (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 2, folder “Bicentennial Speeches (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 2 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON June 28, 1976 MEMORANDUM FOR ROBERT ORBEN VIA: GWEN ANDERSON FROM: CHARLES MC CALL SUBJECT: PRE-ADVANCE REPORT ON THE PRESIDENT'S ADDRESS AT THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES Attached is some background information regarding the speech the President will make on July 2, 1976 at the National Archives. ***************************************************************** TAB A The Event and the Site TAB B Statement by President Truman dedicating the Shrine for the Delcaration, Constitution, and Bill of Rights, December 15, 1952. r' / ' ' ' • THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON June 28, 1976 MEMORANDUM FOR BOB ORBEN VIA: GWEN ANDERSON FROM: CHARLES MC CALL SUBJECT: NATIONAL ARCHIVES ADDENDUM Since the pre-advance visit to the National Archives, the arrangements have been changed so that the principal speakers will make their addresses inside the building . -

Thesis-1972D-C289o.Pdf (5.212Mb)

OKLAHOMA'S UNITED STATES HOUSE DELEGATION AND PROGRESSIVISM, 1901-1917 By GEORGE O. CARNE~ // . Bachelor of Arts Central Missouri State College Warrensburg, Missouri 1964 Master of Arts Central Missouri State College Warrensburg, Missouri 1965 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1972 OKLAHOMA STATE UNiVERSITY LIBRARY MAY 30 1973 ::.a-:r...... ... ~·· .. , .• ··~.• .. ,..,,.·· ,,.,., OKLAHOMA'S UNITED STATES HOUSE DELEGATION AND PROGRESSIVIS~, 1901-1917 Thesis Approved: Oean of the Graduate College PREFACE This dissertation is a study for a single state, Oklahoma, and is designed to test the prevailing Mowry-Chandler-Hofstadter thesis concerning progressivism. The "progressive profile" as developed in the Mowry-Chandler-Hofstadter thesis characterizes the progressive as one who possessed distinctive social, economic, and political qualities that distinguished him from the non-progressive. In 1965 in a political history seminar at Central Missouri State College, Warrensburg, Missouri, I tested the above model by using a single United States House representative from the state of Missouri. When I came to the Oklahoma State University in 1967, I decided to expand my test of this model by examining the thirteen representatives from Oklahoma during the years 1901 through 1917. In testing the thesis for Oklahoma, I investigated the social, economic, and political characteristics of the members whom Oklahoma sent to the United States House of Representatives during those years, and scrutinized the role they played in the formulation of domestic policy. In addition, a geographical analysis of the various Congressional districts suggested the effects the characteristics of the constituents might have on the representatives. -

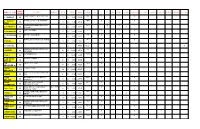

3-VIEWS - TABLE of CONTENTS to Search: Hold "Ctrl" Key Then Press "F" Key

3-VIEWS - TABLE of CONTENTS To search: Hold "Ctrl" key then press "F" key. Enter manufacturer or model number in search box. Click your back key to return to the search page. It is highly recommended to read Order Instructions and Information pages prior to selection. Aircraft MFGs beginning with letter A ................................................................. 3 B ................................................................. 6 C.................................................................10 D.................................................................14 E ................................................................. 17 F ................................................................. 18 G ................................................................21 H................................................................. 23 I .................................................................. 26 J ................................................................. 26 K ................................................................. 27 L ................................................................. 28 M ................................................................30 N................................................................. 35 O ................................................................37 P ................................................................. 38 Q ................................................................40 R................................................................ -

Arctic Discovery Seasoned Pilot Shares Tips on Flying the Canadian North

A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT SEPTEMBER 2019 • VOLUME 13, NUMBER 9 • $6.50 Arctic Discovery Seasoned pilot shares tips on flying the Canadian North A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT King September 2019 VolumeAir 13 / Number 9 2 12 30 36 EDITOR Kim Blonigen EDITORIAL OFFICE 2779 Aero Park Dr., Contents Traverse City MI 49686 Phone: (316) 652-9495 2 30 E-mail: [email protected] PUBLISHERS Pilot Notes – Wichita’s Greatest Dave Moore Flying in the Gamble – Part Two Village Publications Canadian Arctic by Edward H. Phillips GRAPHIC DESIGN Rachel Wood by Robert S. Grant PRODUCTION MANAGER Mike Revard 36 PUBLICATIONS DIRECTOR Jason Smith 12 Value Added ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Bucket Lists, Part 1 – John Shoemaker King Air Magazine Be a Box Checker! 2779 Aero Park Drive by Matthew McDaniel Traverse City, MI 49686 37 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 Fax: (231) 946-9588 Technically ... E-mail: [email protected] ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR AND REPRINT SALES 22 Betsy Beaudoin Aviation Issues – 40 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 E-mail: [email protected] New FAA Admin, Advertiser Index ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT PLANE Act Support and Erika Shenk International Flight Plan Phone: 1-800-773-7798 E-mail: [email protected] Format Adopted SUBSCRIBER SERVICES by Kim Blonigen Rhonda Kelly, Mgr. Kelly Adamson Jessica Meek Jamie Wilson P.O. Box 1810 24 Traverse City, MI 49685 1-800-447-7367 Ask The Expert – ONLINE ADDRESS Flap Stories www.kingairmagazine.com by Tom Clements SUBSCRIPTIONS King Air is distributed at no charge to all registered owners of King Air aircraft. -

Chapter III 1927 – Year for Heroes and Headlines

Chapter III 1927 – Year for Heroes and Headlines The year 1927 was called a time of Ballyhoo and Ford and the Hamilton, “fireproof, you know;” they Hoopla and Wonderful Nonsense, a time when stared at the new Stinson, “built right here in everything was bigger and crazier and publicized Northville;” they tugged at the taut wires of the with more headlines than anything that ever sturdy Wacos and peered inside the cabin of the happened before. yellow painted Ryan, said to be just like Lindy’s, It was a time for Home Run Kings and Flagpole except this one was all fixed up with blue mohair Sitters, Beauty Queens and Talking Movies, Race seats like a fine automobile. Riots and Lynchings and Chicago Gang Wars, The spectators watched the airplanes run through Mississippi Floods and Big Radio Broadcast Hook- their takeoff and landing tests and they talked of Ups and Record Airplane Flights. People called one newsreel pictures they’d seen: of transatlantic another Sheiks, and Shebas; they said things like record seekers struggling to take off; “make their “You’re darned tootin,” and “he knows his onions.” getaway,” as the papers called it, dangerously Flaming Youth drove their Whoopies down the overloaded with hundreds of gallons of “high Main Drag and picked up Daring Flappers who test gasoline.” wore their skirts Two Inches Above the Knee and And the tour officials, mindful of all this scare smoked Tailor-Mades and drank Bootleg Hooch talk, changed the rules to eliminate the full-throttle from Hip Flasks just like their Boy Friends did. -

University of Maine, World War II, in Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K)

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine General University of Maine Publications University of Maine Publications 1946 University of Maine, World War II, In Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K) University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Repository Citation University of Maine, "University of Maine, World War II, In Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K)" (1946). General University of Maine Publications. 248. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications/248 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in General University of Maine Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF MAINE WORLD WAR II IN MEMORIAM DEDICATION In this book are the records of those sons of Maine who gave their lives in World War II. The stories of their lives are brief, for all of them were young. And yet, behind the dates and the names of places there shines the record of courage and sacrifice, of love, and of a devotion to duty that transcends all thought of safety or of gain or of selfish ambition. These are the names of those we love: these are the stories of those who once walked with us and sang our songs and shared our common hope. These are the faces of our loved ones and good comrades, of sons and husbands. There is no tribute equal to their sacrifice; there is no word of praise worthy of their deeds. -

Name of Plan Wing Span Details Source Area Price Ama Ff Cl Ot Scale Gas Rubber Electric Other Glider 3 View Engine Red. Ot C

WING NAME OF PLAN DETAILS SOURCE AREA PRICE AMA POND RC FF CL OT SCALE GAS RUBBER ELECTRIC OTHER GLIDER 3 VIEW ENGINE RED. OT SPAN COMET MODEL AIRPLANE CO. 7D4 X X C 1 PURSUIT 15 3 $ 4.00 33199 C 1 PURSUIT FLYING ACES CLUB FINEMAN 80B5 X X 15 3 $ 4.00 30519 (NEW) MODEL AIRPLANE NEWS 1/69, 90C3 X X C 47 PROFILE 35 SCHAAF 5 $ 7.00 31244 X WALT MOONEY 14F7 X X X C A B MINICAB 20 3 $ 4.00 21346 C L W CURLEW BRITISH MAGAZINE 6D6 X X X 15 2 $ 3.00 20416 T 1 POPULAR AVIATION 9/28, POND 40E5 X X C MODEL 24 4 $ 5.00 24542 C P SPECIAL $ - 34697 RD121 X MODEL AIRPLANE NEWS 4/42, 8A6 X X C RAIDER 68 LATORRE 21 $ 23.00 20519 X AEROMODELLO 42D3 X C S A 1 38 9 $ 12.00 32805 C.A.B. GY 20 BY WALT MOONEY X X X 20 4 $ 6.00 36265 MINICAB C.W. SKY FLYER PLAN 15G3 X X HELLDIVER 02 15 4 $ 5.00 35529 C2 (INC C130 H PLAMER PLAN X X X 133 90 $ 122.00 50587 X HERCULES QUIET & ELECTRIC FLIGHT INT., X CABBIE 38 5/06 6 $ 9.00 50413 CABIN AEROMODELLER PLAN 8/41, 35F5 X X 20 4 $ 5.00 23940 BIPLANE DOWNES CABIN THE OAKLAND TRIBUNE 68B3 X X 20 3 $ 4.00 29091 COMMERCIAL NEWSPAPER 1931 Indoor Miller’s record-holding Dec. 1979 X Cabin Fever: 40 Manhattan Cabin. -

The Saga of Amelia Earhart – Leading Women Into Flight Emilio F

The Journal of Values-Based Leadership Volume 12 Article 17 Issue 2 Summer/Fall 2019 July 2019 The aP ssion to Fly and to the Courage to Lead: The Saga of Amelia Earhart – Leading Women into Flight Emilio F. Iodice [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Iodice, Emilio F. (2019) "The asP sion to Fly and to the Courage to Lead: The aS ga of Amelia Earhart – Leading Women into Flight," The Journal of Values-Based Leadership: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 17. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.22543/0733.122.1285 Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl/vol12/iss2/17 This Case Study is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ourJ nal of Values-Based Leadership by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Passion to Fly and to the Courage to Lead The Saga of Amelia Earhart – Leading Women into Flight EMILIO IODICE, ROME, ITALY Amelia Earhart, 1937, Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC In Her Own Words Everyone has oceans to fly, if they have the heart to do it. Is it reckless? Maybe. But what do dreams know of boundaries? Never interrupt someone doing something you said couldn’t be done. Some of us have great runways already built for us. If you have one, take off! But if you don’t have one, realize it is your responsibility to grab a shovel and build one for yourself and for those who will follow after you. -

APH Fall 2018 Issue Final

FALL 2018 - Volume 65, Number 3 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

SCC Catalog 2016-2017

SCC Catalog 2016-2017 Southeast Community College Program Chart 1-2 General Education Requirements 3-5 Programs of Study • Academic Transfer 6-52 • Agriculture-Welding 53-187 Course Descriptions 188-323 Student Services 324-421 Personnel 422-471 SCC Catalog 2016-2017 Southeast Community College 2016-2017 PROGRAMS of Study & Divisions at SCC LOCATION LENGTH IN COMPREHENSIVE CHART OF PROGRAMS/DIVISIONS AWARD STARTING TERMS OFFERED MONTHS AGRICULTURE/FOOD/NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION Agriculture Business & Management Technology AAS: Agribusiness focus, Agronomy focus, Diversified Agriculture focus, (B) 24 AAS/Cert All Golf and Sports Turf Management focus, Horticulture focus, Livestock Production focus Cert: Precision Agriculture Food Service/Hospitality AAS: Baking/Pastry focus, Culinary Arts focus, Food Service Management focus (L) 18 AAS/Dip/Cert All Dip: Food Service/Hospitality Cert: Event-Venue Operations Management, Food Industry Manager ARTS & SCIENCES DIVISION Academic Transfer (B/L) 18-24 AA/AS All BUSINESS DIVISION Business Administration AAS: Business Administration Dip: Business Administration (B/L/M) O 18 AAS/Dip/Cert All Cert: Business Administration, Client Relations, Entrepreneurship, Event-Venue Operations Management Office Professional AAS: Administrative Office focus, Legal Office focus, Medical Office focus (B/L) O 18 AAS/Dip/Cert All Dip: General Office Cert: General Office, Microsoft Office COMMUNICATIONS & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DIVISION Computer Information Technology AAS: Applications Development focus, Networking, -

72Nd FIGHTER SQUADRON

72nd FIGHTER SQUADRON MISSION LINEAGE 72nd Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) constituted, 4 Oct 1941 Activated, 5 Oct 1941 Redesignated 72nd Fighter Squadron, 15 May 1942 Inactivated, 10 Oct 1946 Redesignated 72nd Fighter Bomber Squadron, 15 Nov 1952 Activated, 1 Jan 1953 Inactivated, 8 Feb 1958 Redesignated 72nd Tactical Fighter Squadron, 19 May 1958 Activated, 1 Jul 1958 Inactivated, 9 Apr 1959 Redesignated 72nd Tactical Fighter Training Squadron and activated, 1 Jul 1982 Redesignated 72nd Fighter Squadron, 1 Nov 1991 Inactivated, 19 Jun 1992 STATIONS Wheeler Field, TH, 5 Oct 1941 Hilo Field, TH, 25 Jul 1943 Wheeler Field, TH, 21 Oct 1943 Makin, 18 Dec 1943 Haleiwa Field, TH, 23 Apr 1944 Mokuleia Field, TH, 8 Jun 1944 Iwo Jima, 26 Mar 1945 Isley Field, Saipan, 5 Dec 1945 Northwest Field, Guam, 17 Apr-10 Oct 1946 George AFB, Calif, 1 Jan 1953-26 Nov 1954 ChateaurouX, France, 14 Dec 1954 Chambley AB, France, 9 Ju1 1955-8 Feb 1958 Clark AB, Luzon, 1 Jul 1958-9 Apr 1959 MacDill AFB, FL 1982-1992 ASSIGNMENTS 15th Pursuit (later Fighter) Group, 5 Oct 1941 318th Fighter Group, 15 Oct 1942 21st Fighter Group, 15 Jun 1944-10 Oct 1946 21st Fighter Bomber Group, 1 Jan 1953-8 Feb 1958 6200th Air Base Wing, 1 Jul 1958-9 Apr 1959 56th Tactical Training Wing 1982-1 Nov 1991 56th Operations Group WEAPON SYSTEMS P-40, 1941-1943 P-39, 1943-1944 P-39Q P-38, 1944-1945 P-38J P-38L P-51, 1944-1946 P-51D P-47, 1946 F-51, 1953 F-51D F-86, 1953-1957 F-100, 1958-1959 F-16C F-16D COMMANDERS HONORS Service Streamers None Campaign Streamers Central Pacific Air Offensive Japan Eastern Mandates Air Combat, Asiatic-Pacific Theater Armed Forces Expeditionary Streamers Decorations Distinguished Unit Citation Japan, 7 Apr 1945 EMBLEM On a red disc within a black border edged Air Force golden yellow, a stylized silhouette of a bird in profile, its upraised wings eXtending over the border in sinister chief, its claws grasping three lightning flashes, all white; in the bird's beak a green olive branch; on the border in chief three white stars, in base the motto, letters white. -

Artist Bios Alex Katz Is the Author of Invented Symbols

Artist Bios Alex Katz is the author of Invented Symbols: An Art Autobiography. Current exhibitions include “Alex Katz: Selections from the Whitney Museum of American Art” at the Nassau County Museum of Art and “Alex Katz: Beneath the Surface” at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. Jan Henle grew up in St. Croix and now works in Puerto Rico. His film drawings are in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. His collaborative film with Vivien Bittencourt, Con El Mismo Amor, was shown at the Gwang Ju Biennale in 2008 and is currently in the ikono On Air Festival. Juan Eduardo Gómez is an American painter born in Colombia in 1970. He came to New York to study art and graduated from the School of Visual Arts in 1998. His paintings are in the collections of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick. He was awarded The Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation Award from American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2007. Rudy Burckhardt was born in Basel in 1914 and moved to New York in 1935. From then on he was at or near the center of New York’s intellectual life, counting among his collaborators Edwin Denby, Paul Bowles, John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, Alex Katz, Red Grooms, Mimi Gross, and many others. His work has been the subject of exhibitions at the Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, the Museum of the City of New York, and, in 2013, at Museum der Moderne Salzburg.