The Servilian Triens Reconsidered*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

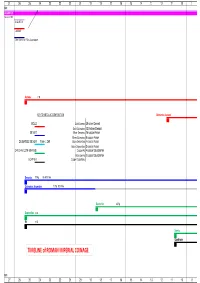

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

Currency, Bullion and Accounts. Monetary Modes in the Roman World

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography 1 Currency, bullion and accounts. Monetary modes in the Roman world Koenraad Verboven in Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Numismatiek en Zegelkunde/ Revue Belge de Numismatique et de Sigillographie 155 (2009) 91-121 Finley‟s assertion that “money was essentially coined metal and nothing else” still enjoys wide support from scholars1. The problems with this view have often been noted. Coins were only available in a limited supply and large payments could not be carried out with any convenience. Travelling with large sums in coins posed both practical and security problems. To quote just one often cited example, Cicero‟s purchase of his house on the Palatine Hill for 3.5 million sesterces would have required 3.4 tons of silver denarii2. Various solutions have been proposed : payments in kind or by means of bullion, bank money, transfer of debt notes or sale credit. Most of these combine a functional view of money („money is what money does‟) with the basic belief that coinage in the ancient world was the sole dominant monetary instrument, with others remaining „second-best‟ alternatives3. Starting from such premises, research has focused on identifying and assessing the possible alternative instruments to effectuate payments. Typical research questions are for instance the commonness (or not) of giro payments, the development (or underdevelopment) of financial instruments, the monetary nature (or not) of ancient debt notes, the commonness (or not) of payments in kind, and so forth. Despite Ghent University, Department of History 1 M. -

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6 Ancient Rome Table of Measures of Length/Distance Name of Unit (Greek) Digitus Meters 01-Digitus (Daktylos) 1 0.0185 02-Uncia - Polex 1.33 0.0246 03-Duorum Digitorum (Condylos) 2 0.037 04-Palmus (Pala(i)ste) 4 0.074 05-Pes Dimidius (Dihas) 8 0.148 06-Palma Porrecta (Orthodoron) 11 0.2035 07-Palmus Major (Spithame) 12 0.222 08-Pes (Pous) 16 0.296 09-Pugnus (Pygme) 18 0.333 10-Palmipes (Pygon) 20 0.370 11-Cubitus - Ulna (pechus) 24 0.444 12-Gradus – Pes Sestertius (bema aploun) 40 0.74 13-Passus (bema diploun) 80 1.48 14-Ulna Extenda (Orguia) 96 1.776 15-Acnua -Dekempeda - Pertica (Akaina) 160 2.96 16-Actus 1920 35.52 17-Actus Stadium 10000 185 18-Stadium (Stadion Attic) 10000 185 19-Milliarium - Mille passuum 80000 1480 20-Leuka - Leuga 120000 2220 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 2 of 6 Table of Measures of Area Name of Unit Pes Quadratus Meters2 01-Pes Quadratus 1 0.0876 02-Dimidium scrupulum 50 4.38 03-Scripulum - scrupulum 100 8.76 04-Actus minimus 480 42.048 05-Uncia 2400 210.24 06-Clima 3600 315.36 07-Sextans 4800 420.48 08-Actus quadratus 14400 1261.44 09-Arvum - Arura 22500 1971 10-Jugerum 28800 2522.88 11-Heredium 57600 5045.76 12-Centuria 5760000 504576 13-Saltus 23040000 2018304 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 3 of 6 Table of Measures of Liquids Name of Unit Ligula Liters 01-Ligula 1 0.0114 02-Uncia (metric) 2 0.0228 03-Cyathus 4 0.0456 04-Acetabulum 6 0.0684 05-Sextans 8 0.0912 06-Quartarius – Quadrans 12 0.1368 -

Cuomo, Serafina (2007) Measures for an Emperor: Volusius Maecianus’ Monetary Pamphlet for Marcus Aurelius

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Birkbeck ePrints: an open access repository of the research output of Birkbeck College http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Cuomo, Serafina (2007) Measures for an emperor: Volusius Maecianus’ monetary pamphlet for Marcus Aurelius. In: König, Jason and Whitmarsh, Tim Ordering knowledge in the Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp.206- 228. This is an author-produced version of a chapter published by Cambridge University Press in 2007 (ISBN 9780521859691). All articles available through Birkbeck ePrints are protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. © Cambridge University Press 2007. Reprinted with permission. Citation for this version: Cuomo, Serafina (2007) Measures for an emperor: Volusius Maecianus’ monetary pamphlet for Marcus Aurelius. London: Birkbeck ePrints. Available at: http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/631 Citation for the publisher’s version: Cuomo, Serafina (2007) Measures for an emperor: Volusius Maecianus’ monetary pamphlet for Marcus Aurelius. In: König, Jason and Whitmarsh, Tim Ordering knowledge in the Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp.206-228. http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Contact Birkbeck ePrints at [email protected] 1 Measures for an emperor: Volusius Maecianus’ monetary pamphlet for Marcus Aurelius To the Greeks the Muse gave intellect and well-rounded speech; they are greedy only for praise. Roman children, with lengthy calculations, learn to divide the as into a hundred parts.1 Like many clichés, Horace’s sour depiction of Roman pragmatism has some truth to it – except that the Greeks were just as interested as the Romans in correctly dividing currency into parts. -

Aguirre-Santiago-Thesis-2013.Pdf

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE SIC SEMPER TYRANNIS: TYRANNICIDE AND VIOLENCE AS POLITICAL TOOLS IN REPUBLICAN ROME A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in History By Santiago Aguirre May 2013 The thesis of Santiago Aguirre is approved: ________________________ ______________ Thomas W. Devine, Ph.D. Date ________________________ ______________ Patricia Juarez-Dappe, Ph.D. Date ________________________ ______________ Frank L. Vatai, Ph.D, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii DEDICATION For my mother and father, who brought me to this country at the age of three and have provided me with love and guidance ever since. From the bottom of my heart, I want to thank you for all the sacrifices that you have made to help me fulfill my dreams. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank Dr. Frank L. Vatai. He helped me re-discover my love for Ancient Greek and Roman history, both through the various courses I took with him, and the wonderful opportunity he gave me to T.A. his course on Ancient Greece. The idea to write this thesis paper, after all, was first sparked when I took Dr. Vatai’s course on the Late Roman Republic, since it made me want to go back and re-read Livy. I also want to thank Dr. Patricia Juarez-Dappe, who gave me the opportunity to read the abstract of one of my papers in the Southwestern Social Science Association conference in the spring of 2012, and later invited me to T.A. one of her courses. -

3927 25.90 Brass 6 Obols / Sestertius 3928 24.91

91 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS 3927 25.90 brass 6 obols / sestertius 3928 24.91 brass 6 obols / sestertius 3929 14.15 brass 3 obols / dupondius 3930 16.23 brass same (2 examples weighed) 3931 6.72 obol / 2/3 as (3 examples weighed) 3932 9.78 3/2 obol / as *Not struck at a Cypriot mint. 92 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS Cypriot Coinage under Tiberius and Later, After 14 AD To the people of Cyprus, far from the frontiers of the Empire, the centuries of the Pax Romana formed an uneventful although contented period. Mattingly notes, “Cyprus . lay just outside of the main currents of life.” A population unused to political independence or democratic institutions did not find Roman rule oppressive. Radiate Divus Augustus and laureate Tiberius on c. 15.6g Cypriot dupondius - triobol. In c. 15-16 AD the laureate head of Tiberius was paired with Livia seated right (RPC 3919, as) and paired with that of Divus Augustus (RPC 3917 and 3918 dupondii). Both types are copied from Roman Imperial types of the early reign of Tiberius. For his son Drusus, hemiobols were struck with the reverse designs begun by late in the reign of Cleopatra: Zeus Salaminios and the Temple of Aphrodite at Paphos. In addition, a reverse with both of these symbols was struck. Drusus obverse was paired with either Zeus Salaminios, or Temple of Aphrodite reverses, as well as this reverse that shows both. (4.19g) Conical black stone found in 1888 near the ruins of the temple of Aphrodite at Paphos, now in the Museum of Kouklia. -

Roman Coins Elementary Manual

^1 If5*« ^IP _\i * K -- ' t| Wk '^ ^. 1 Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTBRS, MACON (PRANCi) Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL COMPILED BY CAV. FRANCESCO gNECCHI VICE-PRBSIDENT OF THE ITALIAN NUMISMATIC SOaETT, HONORARY MEMBER OF THE LONDON, BELGIAN AND SWISS NUMISMATIC SOCIBTIES. 2"^ EDITION RKVISRD, CORRECTED AND AMPLIFIED Translated by the Rev<> Alfred Watson HANDS MEMBF,R OP THE LONDON NUMISMATIC SOCIETT LONDON SPINK & SON 17 & l8 PICCADILLY W. — I & 2 GRACECHURCH ST. B.C. 1903 (ALL RIGHTS RF^ERVED) Digitized by Google Arc //-/7^. K.^ Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL AUTHOR S PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION In the month of July 1898 the Rev. A. W. Hands, with whom I had become acquainted through our common interests and stud- ieSy wrote to me asking whether it would be agreeable to me and reasonable to translate and publish in English my little manual of the Roman Coinage, and most kindly offering to assist me, if my knowledge of the English language was not sufficient. Feeling honoured by the request, and happy indeed to give any assistance I could in rendering this science popular in other coun- tries as well as my own, I suggested that it would he probably less trouble ii he would undertake the translation himselt; and it was with much pleasure and thankfulness that I found this proposal was accepted. It happened that the first edition of my Manual was then nearly exhausted, and by waiting a short time I should be able to offer to the English reader the translation of the second edition, which was being rapidly prepared with additions and improvements. -

GREEK and ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek

GREEK AND ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek coins were struck from blank pieces of metal first prepared by heating and casting in molds of suitable size. At the same time, the weight was adjusted. Next, the blanks were stamped with devices which had been prepared on the dies. The lower die, for the obverse, was fixed in the anvil; the reverse was attached to a punch. The metal blank, heated to soften it, was placed on the anvil and struck with the punch, thus producing a design on both sides of the blank. Weights and Values The values of Greek coins were strictly related to the weights of the coins, since the coins were struck in intrinsically valuable metals. All Greek coins were issued according to the particular weight system adopted by the issuing city-state. Each system was based on the weight of the principal coin; the weights of all other coins of that system were multiples or sub-divisions of this major denomination. There were a number of weight standards in use in the Greek world, but the basic unit of weight was the drachm (handful) which was divided into six obols (spits). The drachm, however, varied in weight. At Aigina it weighed over six grammes, at Corinth less than three. In the 6th century B.C. many cities used the standard of the island of Aegina. In the 5th century, however, the Attic standard, based on the Athenian tetradrachm of 17 grammes, prevailed in many areas of Greece, and this was the system adopted in the 4th century by Alexander the Great. -

Coins in the New Testament

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 16 7-1-1996 Coins in the New Testament Nanci DeBloois Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation DeBloois, Nanci (1996) "Coins in the New Testament," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 36 : Iss. 3 , Article 16. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol36/iss3/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DeBloois: Coins in the New Testament coins in the new testament nanci debloois the coins found at masada ptolemaic seleucid herodian roman jewish tyrian nabatean etc testify not only of the changing fortunes ofjudeaof judea but also of the variety of coins circu- lating in that and neighboring countries during this time such diversity generates some difficulty in identifying the coins men- tioned in the new testament since the beginnings of coinage in the seventh or sixth cen- turies BC judea had been under the control of the persians alexander the great and his successors the Ptoleptolemiesmies of egypt and the seleucids of Pergapergamummum as well as local leaders such as the hasmoneansHasmoneans because of internal discord about 37 BC rome became involved in the political and military affairs of the area with the result that judea became -

Nummi Serrati, Bigati Et Alii. Coins of the Roman Republic in East-Central Europe North of the Sudetes and the Carpathians

Chapter 2 Outline history of Roman Republican coinage The study of the history of the coinage of the Roman state, including that of the Republican Period, has a history going back several centuries. In the past two hundred years in particular there has been an impressive corpus of relevant literature, such as coin catalogues and a wide range of analytical-descriptive studies. Of these the volume essential in the study of Roman Republican coinage defi nitely continues to be the catalogue provided with an extensive commentary written by Michael H. Crawford over forty years ago.18 Admittedly, some arguments presented therein, such as the dating proposed for particular issues, have met with valid criticism,19 but for the study of Republican coin fi nds from northern territories, substantially removed from the Mediterranean world, this is a minor matter. In the study of coin fi nds recovered in our study area from pre-Roman and Roman period prehistoric contexts, we have very few, and usually quite vague, references to an absolute chronology (i.e. the age determined in years of the Common Era) therefore doubts as to the very precise dating of some of the coin issues are the least of our problems. This is especially the case when these doubts are raised mostly with respect to the older coins of the series. These types seem to have entered the territory to the north of the Sudetes and the Carpathians a few score, and in some cases, even over a hundred, years after their date of minting. It is quite important on the other hand to be consistent in our use of the chronological fi ndings related to the Roman Republican coinage, in our case, those of M.