Daily Life in Ancient Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

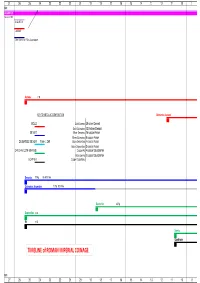

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

The Use of Propaganda on an Augustan Denarius

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Featured Research Undergraduate Student Research Fall 11-2013 The Use of Propaganda on an Augustan Denarius Jens Ibsen Pepperdine University, [email protected] Melissa Miller Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/sturesearch Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Ibsen, Jens and Miller, Melissa, "The Use of Propaganda on an Augustan Denarius" (2013). Pepperdine University, Featured Research. Paper 79. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/sturesearch/79 This Research Poster is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Student Research at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Featured Research by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The Use of Propaganda on an Augustan Denarius Jens Ibsen & Melissa Miller ABSTRACT Our coin is a silver denarius minted in Lugdunum (now Lyon), most likely under the reign of Augustus, the first emperor of Rome. There are factors which point to a possibility of the coin being a restitution Above: A Comparable Trajan AR Denarius(c. 98 -117 CE) issue minted under either Trajan or Hadrian, such as its pristine Source; http://tjbuggey.ancients.info/ condition, which implies a lack of use, and the similarity of symbols employed on this denarius and denarii of Trajan’s era. The coin is a prime example of Augustus’ use of propaganda inserted into Roman daily life to sell the idea of empire to a Roman people who ardently defended a long-standing tradition of republican government. -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

Three Main Groups of People Settled on Or Near the Italian Peninsula and Influenced Roman Civilization

Three main groups of people settled on or near the Italian peninsula and influenced Roman civilization. The Latins settled west of the Apennine Mountains and south of the Tiber River around 1000 B.C.E. While there were many advantages to their location near the river, frequent flooding also created problems. The Latin’s’ settlements were small villages built on the “Seven Hills of Rome”. These settlements were known as Latium. The people were farmers and raised livestock. They spoke their own language which became known as Latin. Eventually groups of these people united and formed the city of Rome. Latin became its official language. The Etruscans About 400 years later, another group of people, the Etruscans, settled west of the Apennines just north of the Tiber River. Archaeologists believe that these people came from the eastern Mediterranean region known as Asia Minor (present day Turkey). By 600 B.C.E., the Etruscans ruled much of northern and central Italy, including the town of Rome. The Etruscans were excellent builders and engineers. Two important structures the Romans adapted from the Etruscans were the arch and the cuniculus. The Etruscan arch rested on two pillars that supported a half circle of wedge-shaped stones. The keystone, or center stone, held the other stones in place. A cuniculus was a long underground trench. Vertical shafts connected it to the ground above. Etruscans used these trenches to irrigate land, drain swamps, and to carry water to their cities. The Romans adapted both of these structures and in time became better engineers than the Etruscans. -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

Santamariaprrojadobe.Pdf

From: Virtual Reality in Archaeology, British Archaeological Reports International Series S 843, ed. J. A. Barcelo, M. Forte, and D. H. Sanders (ArcheoPress, Oxford 2000) 155-162. Virtual Reality and Ancient Rome: The UCLA Cultural VR Lab's Santa Maria Maggiore Project Prof. Bernard Frischer (UCLA Department of Classics; Director, UCLA Cultural VR Lab) Prof. Diane Favro (UCLA Department of Architecture and Urban Design) Dr. Paolo Liverani (Vatican Museums, Department of Classical Antiquities) Prof. Sible De Blaauw (Istituto Olandese di Roma) Dean Abernathy, Architect and Doctoral Student (UCLA Department of Architecture and Urban Design) (1) Introduction Since the fall of 1995, professors of Classics, Architecture, Education, and Information Science at UCLA, in conjunction with colleagues in the United States, Britain, and Italy, have been developing virtual reality (VR) models of buildings and monuments in ancient Rome (cf. fig. 1). This collaborative research effort is called the Rome Reborn Project in honor of the first systematic study of Roman topography, Flavio Biondo's mid-fifteenth century Roma Instaurata (de Grummond 1996: 160-61). Since January, 1998 the project has been housed in the UCLA Cultural VR Lab, which was created with support from Intel, the Creative Kids Education Foundation, Mr. Kirk Mathews, the UCLA Division of Humanities, the UCLA Humanities Computing Facility, the UCLA Center for Digital Innovation, the UCLA Graduate Division, the UCLA Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, and the UCLA College of Letters and Science. The Lab's mission is to provide technology support for projects like Rome Reborn that strive to recreate authenticated three-dimensional computer models of sites of great historic and cultural interest around the world. -

Religion and Culture in Ancient Rome

SOCIAL FORMATIONS AND CULTURAL PATTERNS OF THE MEDIEVAL WORLD TDC 2ND SEMESTER (MAJOR) CBCS CHAP.IV (RELIGION AND CULTURE IN ANCIENT ROME) BY : DR. BIMAN HAZARIKA HO.D & ASSOCATE PROF., DEPT.OF HISTORY DHING COLLEGE 04-05-2020 [WEBSITE AND CONTACT DETAILS] RELIGION AND CULTURE IN ANCIENT ROME : Augustus brought to an end of the Roman Republic Republic. He had estblioshed unity and good government which the Mediterranean world had never known before. For the protecytion of the frontier of his country he made legions composed of Roman citizens and also auxiliary forces composed of men from the provinces. He took special care to protect the frontier on the Rhine and the Danube to check the incursions of the Barbarians. Reforms: Important reforms were introduced in the government to make it more efficient. He established an imp[erail civil service. It included the government officials chosen mostly from the misddle class and these officials were paid by the state. In the inner provinces senators wer allowed to stay on as governors.They were paid salaries and were under the personal supervision of Augustus so that they were not able to overtax the people for ttheir personal gains. Owing to peace and good government, the whole of Mediterranean which had become just like Roman lake, was having thousands sailining across it.There was flowing a brisk trade throughout the empire. As the ruins of Pompi and other cities show, they were full of wealth and prosperity. Age of Augustus why its called Golden Age ? Like Periclean age in ancient Greece the Augustan age in the Roman empire called a golden age because it was characteriseed by conditions of peace and prosperity.and development of artand literature.Virgil, Aeoneid Hoarce were well known literary figure for their lyrics. -

Ancient Rome

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY Ancient Julius Caesar Rome Reader Caesar Augustus The Second Punic War Cleopatra THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. Ancient Rome Reader Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. -

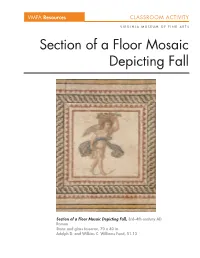

Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall

VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall, 3rd–4th century AD Roman Stone and glass tesserae, 70 x 40 in. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13 VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Object Information Romans often decorated their public buildings, villas, and houses with mosaics—pictures or patterns made from small pieces of stone and glass called tesserae (tes’-er-ray). To make these mosaics, artists first created a foundation (slightly below ground level) with rocks and mortar and then poured wet cement over this mixture. Next they placed the tesserae on the cement to create a design or a picture, using different colors, materials, and sizes to achieve the effects of a painting and a more naturalistic image. Here, for instance, glass tesserae were used to add highlights and emphasize the piled-up bounty of the harvest in the basket. This mosaic panel is part of a larger continuous composition illustrating the four seasons. The seasons are personified aserotes (er-o’-tees), small boys with wings who were the mischievous companions of Eros. (Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, the Greek god and goddess of love, were known in Rome as Cupid and Venus.) Erotes were often shown in a variety of costumes; the one in this panel represents the fall season and wears a tunic with a mantle around his waist. He carries a basket of fruit on his shoulders and a pruning knife in his left hand to harvest fall fruits such as apples and grapes. -

The Earliest Roman Counterfeit by Means of Gold/Mercury Amalgam

The earliest roman counterfeit by means of gold/mercury amalgam Autor(en): Botrè, Claudio / Hurter, Silvia Mani Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 79 (2000) PDF erstellt am: 25.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-175713 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch CLAUDIO BOTRE, SILVIA MANI HURTER THE EARLIEST ROMAN COUNTERFEIT BY MEANS OF GOLD/MERCURY AMALGAM A hoard of Roman coins recently came to light in an excavation conducted by archaeologists of the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma under the direction of Dott. -

Currency, Bullion and Accounts. Monetary Modes in the Roman World

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography 1 Currency, bullion and accounts. Monetary modes in the Roman world Koenraad Verboven in Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Numismatiek en Zegelkunde/ Revue Belge de Numismatique et de Sigillographie 155 (2009) 91-121 Finley‟s assertion that “money was essentially coined metal and nothing else” still enjoys wide support from scholars1. The problems with this view have often been noted. Coins were only available in a limited supply and large payments could not be carried out with any convenience. Travelling with large sums in coins posed both practical and security problems. To quote just one often cited example, Cicero‟s purchase of his house on the Palatine Hill for 3.5 million sesterces would have required 3.4 tons of silver denarii2. Various solutions have been proposed : payments in kind or by means of bullion, bank money, transfer of debt notes or sale credit. Most of these combine a functional view of money („money is what money does‟) with the basic belief that coinage in the ancient world was the sole dominant monetary instrument, with others remaining „second-best‟ alternatives3. Starting from such premises, research has focused on identifying and assessing the possible alternative instruments to effectuate payments. Typical research questions are for instance the commonness (or not) of giro payments, the development (or underdevelopment) of financial instruments, the monetary nature (or not) of ancient debt notes, the commonness (or not) of payments in kind, and so forth. Despite Ghent University, Department of History 1 M.