3927 25.90 Brass 6 Obols / Sestertius 3928 24.91

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

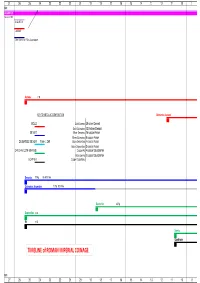

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

2014) ADVANCED)DIVISION) ) Page)1) ROUND)I

MASSACHUSETTS)CERTAMEN),)2014) ADVANCED)DIVISION) ) Page)1) ROUND)I 1:! TU:!!! What!pair!of!Babylonian!lovers!planned!to!meet!at!the!tomb!of!Ninus,!but!were!thwarted!by!a!lioness?) PYRAMUS)AND)THISBE! B1:!!! What!did!Pyramus!do!when!he!found!Thisbe’s!bloody!veil!and!thought!she!was!dead?! ! ! ! ! KILLED)HIMSELF! B2:!!! What!plant!forever!changed!color!when!it!was!splattered!with!Pyramus’!and!Thisbe’s!blood?! ! ! ! ! MULBERRY) ) ) 2:! TU:! For!the!verb!fallō,)give!the!3rd!person!singular,!perfect,!active!subjunctive.! ) FEFELLERIT! B1:! Give!the!corresponding!form!of!disco.! ) DIDICERIT! B2:! Give!the!corresponding!form!of!fio.! ) FACTUS)(A,UM))SIT) ) ) 3:! TU:! Who!was!the!victorious!general!at!the!battle!of!Pydna!in!168!BC?! ) AEMELIUS)PAULUS! B1:! Who!was!the!son!of!Aemelius!Paulus!that!sacked!Corinth!in!146!BC?! ! ! ! ! SCIPIO)AEMELIANUS) ! B2:! Scipio!Aemelianus!was!adopted!by!which!flamen-dialis,-thus!making!him!part!of!a!more!aristocratic!family?! ) (PUBLIUS)CORNELIUS))SCIPIO)AFRICANUS) ) ) 4:! TU:!! According!to!its!derivation,!an!irascible!person!is!easy!to!put!into!what!kind!of!mood?! ) ANGER/ANGRY! B1:!! Give!the!Latin!verb!and!its!meaning!from!which!the!English!word!“sample”!is!derived.) EMŌ)–)TO)BUY! B2:!! Give!the!Latin!noun!and!its!meaning!from!which!the!English!word!“rush”!is!derived.! ) CAUSA)–)REASON,)CAUSE) ) [SCORE)CHECK]) ) 5:! TU:!!! What!Paduan!prose!author!of!the!Augustan!age!wrote!a!history!of!Rome!in!142!books?) TITUS)LIVIUS/LIVY! B1:!!! What!was!the!Latin!title!of!Livy’s!history?! ) AB)URBE)CONDITA! B2:!!! Which!of!the!following!topics!is!not!covered!in!one!of!the!35!extant!books!of!Ab-Urbe-Condita:!!! -

The Aurea Aetas and Octavianic/Augustan Coinage

OMNI N°8 – 10/2014 Book cover: volto della statua di Augusto Togato, su consessione del Ministero dei beni e delle attivitá culturali e del turismo – Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Roma 1 www.omni.wikimoneda.com OMNI N°8 – 11/2014 OMNI n°8 Director: Cédric LOPEZ, OMNI Numismatic (France) Deputy Director: Carlos ALAJARÍN CASCALES, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Editorial board: Jean-Albert CHEVILLON, Independent Scientist (France) Eduardo DARGENT CHAMOT, Universidad de San Martín de Porres (Peru) Georges DEPEYROT, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (France) Jean-Marc DOYEN, Laboratoire Halma-Ipel, UMR 8164, Université de Lille 3 (France) Alejandro LASCANO, Independent Scientist (Spain) Serge LE GALL, Independent Scientist (France) Claudio LOVALLO, Tuttonumismatica.com (Italy) David FRANCES VAÑÓ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Ginés GOMARIZ CEREZO, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Michel LHERMET, Independent Scientist (France) Jean-Louis MIRMAND, Independent Scientist (France) Pere Pau RIPOLLÈS, Universidad de Valencia (Spain) Ramón RODRÍGUEZ PEREZ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Pablo Rueda RODRÍGUEZ-VILa, Independent Scientist (Spain) Scientific Committee: Luis AMELA VALVERDE, Universidad de Barcelona (Spain) Almudena ARIZA ARMADA, New York University (USA/Madrid Center) Ermanno A. ARSLAN, Università Popolare di Milano (Italy) Gilles BRANSBOURG, Universidad de New-York (USA) Pedro CANO, Universidad de Sevilla (Spain) Alberto CANTO GARCÍA, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) Francisco CEBREIRO ARES, Universidade de Santiago -

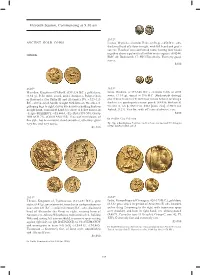

Ancient Coins

ANCIENT COINS 5. Trajan (AD 98-117) silver denarius 3.02gm., AD 108-109, IMP TRAIANO AVG GER DAC P M TR P, laureate bust right, slight drapery on 1. Group of Roman Republican and far shoulder. Rev. COS V P P SPQR OPTIMO Imperatorial silver denarii, various types and PRINC, Roma seated left, holding Victory and issuers including Sulla, Julius Caesar and Sextus spear. (RIC 116), very fine £40-50 Pomepey (21), varying grades from fine to good very fine or better, some with damage and banker’s marks, lot sold as seen, no returns £50-70 *ex Derek Aldred Collection 6. Ancient Rome, Hadrian (117-138), den, laur. head r., differing reverse types, each COS III, 2. Augustus (27 BC - AD 14), Æ 23mm, minted fine or better (3) £200-250 at Antioch, struck 5/4 BC, laureate head facing right, rev S C within a laurel-wreath, 8.45g, 12h (RPC 4248), attractive dark green patina, nearly extremely fine £80-120 3. Tiberius (AD 14-37), Æ As, minted at Romula, 7. Antoninus Pius (AD 138-161), Æ 25mm, Spain, struck c. AD 14-19, PERM DIVI AVG minted at Tripolis, Phoenicia, laureate and COL ROM, laureate head of Tiberius facing left, draped bust facing right, rev Astarte standing rev GERMANICVS CAESAR DRVSVS CAESAR, right, foot on prow, holding a standard (BMC busts of Germanicus and Drusus facing each 59); with Æ 24mm, Berytus, laureate head right, other, 13.22g, 3h (RPC 74), brown patina, good rev Neptune standing left, holding a dolphin and fine £60-80 a trident (SNG Copenhagen 102), dark patina, very fine (2) £60-80 8. -

The Communication of the Emperor's Virtues Author(S): Carlos F

The Communication of the Emperor's Virtues Author(s): Carlos F. Noreña Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 91 (2001), pp. 146-168 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3184774 . Accessed: 01/09/2012 16:45 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Roman Studies. http://www.jstor.org THE COMMUNICATION OF THE EMPEROR'S VIRTUES* By CARLOS F. NORENA The Roman emperor served a number of functions within the Roman state. The emperor's public image reflected this diversity. Triumphal processions and imposing state monuments such as Trajan's Column or the Arch of Septimius Severus celebrated the military exploits and martial glory of the emperor. Distributions of grain and coin, public buildings, and spectacle entertainments in the city of Rome all advertised the emperor's patronage of the urban plebs, while imperial rescripts posted in every corner of the Empire stood as so many witnesses to the emperor's conscientious administration of law and justice. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76423-0 - Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age Jonathan Bardill Index More information INDEX S Abednego, 333 aniketos¯ , 87 Ambrose, bishop of Milan Ablabius, Flavius, praetorian prefect (329–337), Constantine’s affinity with, 87, 293, 397 baptism delayed, 305 220, 275, 278, 303 divinity of, 359–60 Ammianus Marcellinus jealous of Sopater, 304 hailed as “unconquered” by Pythian oracle, Constantius II’s entry into Rome (357), 21 Abraham 16–17 obelisk of Constantius II, 154–55 and Mamre, 259, 265 heavenward gaze, 19 Res Gestae, 3 Acanthus imitates Hercules, 65, 359–60 on sacrifice in Ostia (359), 285 associated with Helios, 46 lion’s mane of hair, 19 Ammon, 359 Achilles, 108 modelled rule on Zeus’ rule, 19 Amnius Manius Caesonius Nicomachus Anicius Actian wreath, 48–49, 397 Octavian and, 17 Paulinus, city prefect (334–335), 302 Actium, battle of (31 B.C.), 128 portraits, 21 Anastasia, daughter of Constantius, 89 Adonis statue of, 152 Anastasius, emperor (491–518) cult of, at Bethlehem, 258 statue of, by Lysippus, 19 burial place in Constantinople, 370 adoratio purpurae statue of, in hippodrome at Constantinople, Anatolius, praetorian prefect of Illyricum and Constantine, 340 20 sacrifices in Athens, 287 and Diocletian, 339 statue of, in Strategion at Constantinople, Anaxagoras, 134 adoratio, 339 26n.64 anchor, 166, 180–81 Adrianople. See Hadrianopolis and Troy, 251 Seleucus’ birthmark, 343 Aelafius worship of, 43 Andrade, E. N. da C. Constantine’s letter to (314), 101, 305, 272, Alexandria, -

234 the FINDS Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-161. Sestertius. Rev. Anona

234 SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY THE FINDS THE COINS Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-161. Sestertius. Rev. Anona. B.M.C. 1654. From mediaeval pit. Julia Domna (wife of Septimius Severus), A.D. 193-211. Denarius. Rev. Juno. R.I.C. 560, B.M.C. 42. From primary silt of Ditch A south section. SeverusAlexander, A.D. 222-235. As. Rev. Sol. R.I.C. 543, B.M.C. 961. From fill of Ditch A west section at depth of one foot seveninches. Gallienus, A.D. 253-268. Antoninianus. Rev. Laetitia Aug. R.I.C. 226. From mediaevalpit. Claudius II, A.D. 268-270. Antoninianus. Rev. Fides Exerci. R.I.C. 36. From mediaeval pit. Tetricus I, A.D. 270-273. Antoninianus. Rev.Virtus Aug. R.I.C. 145. From mediaevalpit. Tetricus I, A.D. 270-273. Antoninianus. Rev. uncertain. From west stoke-hole. 33.—Fragment of stone roofing tile (i). STONE (Fig. 33) By F. W. ANDERSON, D.SC., F.R.S.E. Fragment of stone roofing tile. This has split off parallel to the bedding: only half the depth of the hole is left, assumingthat, as is usual, the hole was bored from both sides. The rock appears to be a limestoneofLowerCarboniferousage. It isthus a foreigner to the area. It was probably made from a glacial erratic boulder in the drift, or else was imported from north England, south Scotland or possiblyBelgium, but it is impossibleto say which is the right answer. One can, however,say that the stone is not that normally usedby the Romans—i.e.it is not Purbeckor Collyweston A ROMANO-BRITISH BATH-HOUSE 235 or Stansfield Slate, nor any of the sandy flagstones used in the West Country.1° 34.—Lead drain pipe (i). -

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

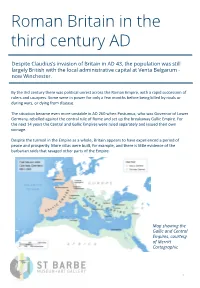

Roman Britain in the Third Century AD

Roman Britain in the third century AD Despite Claudius’s invasion of Britain in AD 43, the population was still largely British with the local administrative capital at Venta Belgarum - now Winchester. By the 3rd century there was political unrest across the Roman Empire, with a rapid succession of rulers and usurpers. Some were in power for only a few months before being killed by rivals or during wars, or dying from disease. The situation became even more unstable in AD 260 when Postumus, who was Governor of Lower Germany, rebelled against the central rule of Rome and set up the breakaway Gallic Empire. For the next 14 years the Central and Gallic Empires were ruled separately and issued their own coinage. Despite the turmoil in the Empire as a whole, Britain appears to have experienced a period of peace and prosperity. More villas were built, for example, and there is little evidence of the barbarian raids that ravaged other parts of the Empire. Map showing the Gallic and Central Empires, courtesy of Merritt Cartographic 1 The Boldre Hoard The Boldre Hoard contains 1,608 coins, dating from AD 249 to 276 and issued by 12 different emperors. The coins are all radiates, so-called because of the radiate crown worn by the emperors they depict. Although silver, the coins contain so little of that metal (sometimes only 1%) that they appear bronze. Many of the coins in the Boldre Hoard are extremely common, but some unusual examples are also present. There are three coins of Marius, for example, which are scarce in Britain as he ruled the Gallic Empire for just 12 weeks in AD 269. -

Currency, Bullion and Accounts. Monetary Modes in the Roman World

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography 1 Currency, bullion and accounts. Monetary modes in the Roman world Koenraad Verboven in Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Numismatiek en Zegelkunde/ Revue Belge de Numismatique et de Sigillographie 155 (2009) 91-121 Finley‟s assertion that “money was essentially coined metal and nothing else” still enjoys wide support from scholars1. The problems with this view have often been noted. Coins were only available in a limited supply and large payments could not be carried out with any convenience. Travelling with large sums in coins posed both practical and security problems. To quote just one often cited example, Cicero‟s purchase of his house on the Palatine Hill for 3.5 million sesterces would have required 3.4 tons of silver denarii2. Various solutions have been proposed : payments in kind or by means of bullion, bank money, transfer of debt notes or sale credit. Most of these combine a functional view of money („money is what money does‟) with the basic belief that coinage in the ancient world was the sole dominant monetary instrument, with others remaining „second-best‟ alternatives3. Starting from such premises, research has focused on identifying and assessing the possible alternative instruments to effectuate payments. Typical research questions are for instance the commonness (or not) of giro payments, the development (or underdevelopment) of financial instruments, the monetary nature (or not) of ancient debt notes, the commonness (or not) of payments in kind, and so forth. Despite Ghent University, Department of History 1 M. -

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6 Ancient Rome Table of Measures of Length/Distance Name of Unit (Greek) Digitus Meters 01-Digitus (Daktylos) 1 0.0185 02-Uncia - Polex 1.33 0.0246 03-Duorum Digitorum (Condylos) 2 0.037 04-Palmus (Pala(i)ste) 4 0.074 05-Pes Dimidius (Dihas) 8 0.148 06-Palma Porrecta (Orthodoron) 11 0.2035 07-Palmus Major (Spithame) 12 0.222 08-Pes (Pous) 16 0.296 09-Pugnus (Pygme) 18 0.333 10-Palmipes (Pygon) 20 0.370 11-Cubitus - Ulna (pechus) 24 0.444 12-Gradus – Pes Sestertius (bema aploun) 40 0.74 13-Passus (bema diploun) 80 1.48 14-Ulna Extenda (Orguia) 96 1.776 15-Acnua -Dekempeda - Pertica (Akaina) 160 2.96 16-Actus 1920 35.52 17-Actus Stadium 10000 185 18-Stadium (Stadion Attic) 10000 185 19-Milliarium - Mille passuum 80000 1480 20-Leuka - Leuga 120000 2220 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 2 of 6 Table of Measures of Area Name of Unit Pes Quadratus Meters2 01-Pes Quadratus 1 0.0876 02-Dimidium scrupulum 50 4.38 03-Scripulum - scrupulum 100 8.76 04-Actus minimus 480 42.048 05-Uncia 2400 210.24 06-Clima 3600 315.36 07-Sextans 4800 420.48 08-Actus quadratus 14400 1261.44 09-Arvum - Arura 22500 1971 10-Jugerum 28800 2522.88 11-Heredium 57600 5045.76 12-Centuria 5760000 504576 13-Saltus 23040000 2018304 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 3 of 6 Table of Measures of Liquids Name of Unit Ligula Liters 01-Ligula 1 0.0114 02-Uncia (metric) 2 0.0228 03-Cyathus 4 0.0456 04-Acetabulum 6 0.0684 05-Sextans 8 0.0912 06-Quartarius – Quadrans 12 0.1368