Meteoritics and Cosmology Among the Aboriginal Cultures of Central Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal History Journal

ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume 38, 2014 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume 38, 2014 Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://press.anu.edu.au All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Editor Shino Konishi, Book Review Editor Luise Hercus, Copy Editor Geoff Hunt. About Aboriginal History Aboriginal History is a refereed journal that presents articles and information in Australian ethnohistory and contact and post-contact history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia, are welcomed. Subjects include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, archival and bibliographic articles, and book reviews. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, Coombs Building (9) ANU, ACT, 0200, or [email protected]. -

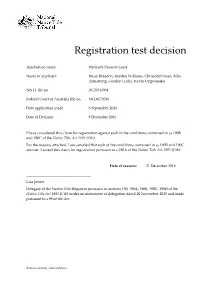

Registration Test Decision

Registration test decision Application name Henbury Pastoral Lease Name of applicant Bruce Breadon, Baydon Williams, Christobel Swan, Felix Armstrong, Gordon Lucky, Kevin Ungwanaka NNTT file no. DC2016/004 Federal Court of Australia file no. NTD47/2016 Date application made 6 September 2016 Date of Decision 9 December 2016 I have considered this claim for registration against each of the conditions contained in ss 190B and 190C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). For the reasons attached, I am satisfied that each of the conditions contained in ss 190B and 190C are met. I accept this claim for registration pursuant to s 190A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). Date of reasons: 21 December 2016 ___________________________________ Lisa Jowett Delegate of the Native Title Registrar pursuant to sections 190, 190A, 190B, 190C, 190D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) under an instrument of delegation dated 20 November 2015 and made pursuant to s 99 of the Act. Shared country, shared future. Reasons for decision Introduction [1] The Registrar of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) gave a copy of the Henbury Pastoral Lease native title determination application (NTD44/2016) to the Native Title Registrar (the Registrar) on 1 September 2016 pursuant to s 63 of the Act1. This has triggered the Registrar’s duty to consider the claim made in the application for registration in accordance with s 190A: see subsection 190A(1). [2] Sections 190A(1A), (6), (6A) and (6B) set out the decisions available to the Registrar under s 190A. Subsection 190A(1A) provides for exemption from the registration test for certain amended applications and s 190A(6A) provides that the Registrar must accept a claim (in an amended application) when it meets certain conditions. -

Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians

Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, 2014. Edited by Helaine Selin. Springer Netherlands, preprint. Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians Duane W. Hamacher Nura Gili Centre for Indigenous Programs, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia Email: [email protected] Of the hundreds of distinct Aboriginal cultures of Australia, many have oral traditions rich in descriptions and explanations of comets, meteors, meteorites, airbursts, impact events, and impact craters. These views generally attribute these phenomena to spirits, death, and bad omens. There are also many traditions that describe the formation of meteorite craters as well as impact events that are not known to Western science. Comets Bright comets appear in the sky roughly once every five years. These celestial visitors were commonly seen as harbingers of death and disease by Aboriginal cultures of Australia. In an ordered and predictable cosmos, rare transient events were typically viewed negatively – a view shared by most cultures of the world (Hamacher & Norris, 2011). In some cases, the appearance of a comet would coincide with a battle, a disease outbreak, or a drought. The comet was then seen as the cause and attributed to the deeds of evil spirits. The Tanganekald people of South Australia (SA) believed comets were omens of sickness and death and were met with great fear. The Gunditjmara people of western Victoria (VIC) similarly believed the comet to be an omen that many people would die. In communities near Townsville, Queensland (QLD), comets represented the spirits of the dead returning home. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

Than One Way to Catch a Frog: a Study of Children's

More than one way to catch a frog: A study of children’s discourse in an Australian contact language Samantha Disbray Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics University of Melbourne December, 2008 Declaration This is to certify that: a. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD b. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all material used c. the text is less than 100,000 words, exclusive of tables, figures, maps, examples, appendices and bibliography ____________________________ Samantha Disbray Abstract Children everywhere learn to tell stories. One important aspect of story telling is the way characters are introduced and then moved through the story. Telling a story to a naïve listener places varied demands on a speaker. As the story plot develops, the speaker must set and re-set these parameters for referring to characters, as well as the temporal and spatial parameters of the story. To these cognitive and linguistic tasks is the added social and pragmatic task of monitoring the knowledge and attention states of their listener. The speaker must ensure that the listener can identify the characters, and so must anticipate their listener’s knowledge and on-going mental image of the story. How speakers do this depends on cultural conventions and on the resources of the language(s) they speak. For the child speaker the development narrative competence involves an integration, on-line, of a number of skills, some of which are not fully established until the later childhood years. -

STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2019 Contents

TOURISM CENTRAL AUSTRALIA STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2019 Contents Introduction from the Chair ..........................................................................3 Our Mission ........................................................................................................4 Our Vision ............................................................................................................4 Our Objectives ...................................................................................................4 Key Challenges ...................................................................................................4 Background .........................................................................................................4 The Facts ..............................................................................................................6 Our Organisation ..............................................................................................8 Our Strengths and Weaknesses ...................................................................8 Our Aspirations ................................................................................................10 Tourism Central Australia - Strategic Focus Areas ...............................11 Improving Visitor Services and Conversion Opportunities ...............11 Strengthening Governance and Planning ..............................................12 Enhancing Membership Services ..............................................................13 Partnering in Product -

The Status of Degrees in Warlpiri

The status of degrees in Warlpiri Margit Bowler, UCLA Stanford Fieldwork Group: November 4, 2015 Stanford University Margit Bowler, UCLA The status of degrees in Warlpiri Roadmap Overview of Australian languages & my fieldwork site My methodologies for collecting degree data −! Methodological issues Background on degrees and degree constructions Presentation of Warlpiri data −! Degree data roughly following Beck, et al. (2009) −! Potentially problematic morphemes/constructions What can this tell us about: −! Degrees in Warlpiri? (They do not exist!) Wrap-up Margit Bowler, UCLA The status of degrees in Warlpiri Australian languages 250-300 languages were spoken when Australia was colonized in the late 1700s; ∼100 languages are spoken today (Dixon 2002) −! Of these, only approximately 20 languages have a robust speaker population; Warlpiri has 3,000 speakers Divided into Pama-Nyungan (90% of languages in Australia) versus non-Pama-Nyungan Margit Bowler, UCLA The status of degrees in Warlpiri Common features of Australian languages (Split-)ergativity −! Warlpiri has ergative case marking, roughly accusative agreement marking Highly flexible word order Extensive pro-drop Adjectives pattern morphosyntactically like nouns −! Host case marking, trigger agreement marking, and so on Margit Bowler, UCLA The status of degrees in Warlpiri Yuendumu, NT ∼300km northwest of Alice Springs, NT Population ∼800, around 90% Aboriginal 95% of children at the Yuendumu school speak Warlpiri as a first language Languages spoken include Warlpiri, Pintupi/Luritja, -

Widespread Excess Ice in Arcadia Planitia, Mars

Widespread Excess Ice in Arcadia Planitia, Mars Ali M. Bramson1, Shane Byrne1, Nathaniel E. Putzig2, Sarah Sutton1, Jeffrey J. Plaut3, T. Charles Brothers4 and John W. Holt4 Corresponding author: A. M. Bramson, Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Kuiper Space Science Building, 1629 E. University Blvd. Tucson, AZ, 85721, USA. ([email protected]) Affiliations: 1Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA. 2Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado, USA. 3Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, USA. 4Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA. Accepted for publication July 18, 2015 in Geophysical Research Letters. An edited version of this paper was published by AGU on August 26, 2015. Copyright 2015 American Geophysical Union. Citation: Bramson, A. M., S. Byrne, N. E. Putzig, S. Sutton, J. J. Plaut, T. C. Brothers, and J. W. Holt (2015), Widespread excess ice in Arcadia Planitia, Mars, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, doi:10.1002/2015GL064844. Key points: • Terraced craters: abundant in Arcadia Planitia, indicate subsurface layering • A widespread subsurface interface is also detected by SHARAD • Combining data sets yields dielectric constants consistent with decameters of excess water ice Abstract: The distribution of subsurface water ice on Mars is a key constraint on past climate, while the volumetric concentration of buried ice (pore-filling versus excess) provides information about the process that led to its deposition. We investigate the subsurface of Arcadia Planitia by measuring the depth of terraces in simple impact craters and mapping a widespread subsurface reflection in radar sounding data. Assuming that the contrast in material strengths responsible for the terracing is the same dielectric interface that causes the radar reflection, we can combine these data to estimate the dielectric constant of the overlying material. -

Coober Pedy, South Australia

The etymology of Coober Pedy, South Australia Petter Naessan The aim of this paper is to outline and assess the diverging etymologies of ‘Coober Pedy’ in northern South Australia, in the search for original and post-contact local Indigenous significance associated with the name and the region. At the interface of contemporary Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara opinion (mainly in the Coober Pedy region, where I have conducted fieldwork since 1999) and other sources, an interesting picture emerges: in the current use by Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people as well as non-Indigenous people in Coober Pedy, the name ‘Coober Pedy’ – as ‘white man’s hole (in the ground)’ – does not seem to reflect or point toward a pre-contact Indigenous presence. Coober Pedy is an opal mining and tourist town with a total population of about 3500, situated near the Stuart Highway, about 850 kilometres north of Adelaide, South Australia. Coober Pedy is close to the Stuart Range, lies within the Arckaringa Basin and is near the border of the Great Victoria Desert. Low spinifex grasslands amounts for most of the sparse vegetation. The Coober Pedy and Oodnadatta region is characterised by dwarf shrubland and tussock grassland. Further north and northwest, low open shrub savanna and open shrub woodland dominates.1 Coober Pedy and surrounding regions are arid and exhibit very unpredictable rainfall. Much of the economic activity in the region (as well as the initial settlement of Euro-Australian invaders) is directly related to the geology, namely quite large deposits of opal. The area was only settled by non-Indigenous people after 1915 when opal was uncovered but traditionally the Indigenous population was western Arabana (Midlaliri). -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

A Preliminary Study of Pitch and Rhythm in Pitjantjatjara

A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF PITCH AND RHYTHM IN PITJANTJATJARA. Marija Tabain (La Trobe University, Melbourne), Janet Fletcher (University of Melbourne), Christian Heinrich (Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich) Pitjantjatjara is a dialect of the greater Western Desert language, spoken mainly in the north-west of South Australia, but extending north into the Northern Territory, and west into Western Australia (Douglas 1964). Like most Australian languages, Pitjantjatjara has been analysed as a stress language (trochaic); however relatively little is known about the intonational system of this language. We present a preliminary analysis of the prosodic structure of Pitjantjatjara based on three female speakers reading two different texts – the Walpa Ulpariranya munu Tjintunya (South Wind and the Sun) passage, and the Nanikuta (Three Billy Goats) text. Our first result suggests that the shape and temporal alignment of major pitch movements perform a largely demarcative function, aligning with the metrically strong first syllable in a word. There is mixed evidence, however, that strong syllables are longer or have more "peripheral" vowels: differences in strong vs. weak syllable duration are text- dependent, while the formant patterns for the three vowel phonemes /i, a, u/ suggest subtle formant differences, rather than categorical changes in vowel quality, according to strong vs. weak syllable. We also consider the traditional rhythm metrics (e.g. vocalic nPVI and intervocalic rPVI). These suggest that Pitjantjatjara is a stress-based language. However, as noted above, Pitjantjatjara does not have vowel reduction in weak syllables, and in addition, it has a predominantly CV syllable structure. Moreover, Australian languages such as Pitjantjatjara have a high proportion of sonorants in their phoneme inventory (Butcher 2006), and despite the mainly CV syllable structure, sonorant coda consonants are possible and not infrequent. -

Australian Aborigines and Meteorites

Records of the Western Australian Museum 18: 93-101 (1996). Australian Aborigines and meteorites A.W.R. Bevan! and P. Bindon2 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 2 Department of Anthropology, Western Australian Museum, Francis Street, Perth, Western Australia 6000 Abstract - Numerous mythological references to meteoritic events by Aboriginal people in Australia contrast with the scant physical evidence of their interaction with meteoritic materials. Possible reasons for this are the unsuitability of some meteorites for tool making and the apparent inability of early Aborigines to work metallic materials. However, there is a strong possibility that Aborigines witnessed one or more of the several recent « 5000 yrs BP) meteorite impact events in Australia. Evidence for Aboriginal use of meteorites and the recognition of meteoritic events is critically evaluated. INTRODUCTION Australia, although for climatic and physiographic The ceremonial and practical significance of reasons they are rarely found in tropical Australia. Australian tektites (australites) in Aboriginal life is The history of the recovery of meteorites in extensively documented (Baker 1957 and Australia has been reviewed by Bevan (1992). references therein; Edwards 1966). However, Within the continent there are two significant areas despite abundant evidence throughout the world for the recovery of meteorites: the Nullarbor that many other ancient civilizations recognised, Region, and the area around the Menindee Lakes utilized and even revered meteorites (particularly of western New South Wales. These accumulations meteoritic iron) (e.g., see Buchwald 1975 and have resulted from prolonged aridity that has references therein), there is very little physical or allowed the preservation of meteorites for documentary evidence of Aboriginal acknowledge thousands of years after their fall, and the large ment or use of meteoritic materials.