FIGHTING OVER COUNTRY: Anthropological Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

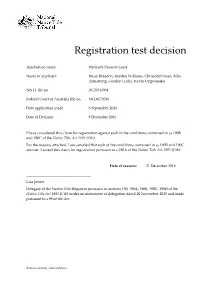

Registration Test Decision

Registration test decision Application name Henbury Pastoral Lease Name of applicant Bruce Breadon, Baydon Williams, Christobel Swan, Felix Armstrong, Gordon Lucky, Kevin Ungwanaka NNTT file no. DC2016/004 Federal Court of Australia file no. NTD47/2016 Date application made 6 September 2016 Date of Decision 9 December 2016 I have considered this claim for registration against each of the conditions contained in ss 190B and 190C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). For the reasons attached, I am satisfied that each of the conditions contained in ss 190B and 190C are met. I accept this claim for registration pursuant to s 190A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). Date of reasons: 21 December 2016 ___________________________________ Lisa Jowett Delegate of the Native Title Registrar pursuant to sections 190, 190A, 190B, 190C, 190D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) under an instrument of delegation dated 20 November 2015 and made pursuant to s 99 of the Act. Shared country, shared future. Reasons for decision Introduction [1] The Registrar of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) gave a copy of the Henbury Pastoral Lease native title determination application (NTD44/2016) to the Native Title Registrar (the Registrar) on 1 September 2016 pursuant to s 63 of the Act1. This has triggered the Registrar’s duty to consider the claim made in the application for registration in accordance with s 190A: see subsection 190A(1). [2] Sections 190A(1A), (6), (6A) and (6B) set out the decisions available to the Registrar under s 190A. Subsection 190A(1A) provides for exemption from the registration test for certain amended applications and s 190A(6A) provides that the Registrar must accept a claim (in an amended application) when it meets certain conditions. -

Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians

Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, 2014. Edited by Helaine Selin. Springer Netherlands, preprint. Comet and Meteorite Traditions of Aboriginal Australians Duane W. Hamacher Nura Gili Centre for Indigenous Programs, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia Email: [email protected] Of the hundreds of distinct Aboriginal cultures of Australia, many have oral traditions rich in descriptions and explanations of comets, meteors, meteorites, airbursts, impact events, and impact craters. These views generally attribute these phenomena to spirits, death, and bad omens. There are also many traditions that describe the formation of meteorite craters as well as impact events that are not known to Western science. Comets Bright comets appear in the sky roughly once every five years. These celestial visitors were commonly seen as harbingers of death and disease by Aboriginal cultures of Australia. In an ordered and predictable cosmos, rare transient events were typically viewed negatively – a view shared by most cultures of the world (Hamacher & Norris, 2011). In some cases, the appearance of a comet would coincide with a battle, a disease outbreak, or a drought. The comet was then seen as the cause and attributed to the deeds of evil spirits. The Tanganekald people of South Australia (SA) believed comets were omens of sickness and death and were met with great fear. The Gunditjmara people of western Victoria (VIC) similarly believed the comet to be an omen that many people would die. In communities near Townsville, Queensland (QLD), comets represented the spirits of the dead returning home. -

STOLEN GENERATIONS’ REPORT by RON BRUNTON

BETRAYING Backgrounder THE VICTIMS THE ‘STOLEN GENERATIONS’ REPORT by RON BRUNTON The seriousness of the ‘stolen generations’ issue should not be underestimated, and Aborigines are fully entitled to demand an acknowledgement of the wrongs that many of them suffered at the hands of various authorities. But both those who were wronged and the nation as a whole are also entitled to an honest and rigorous assessment of the past. This should have been the task of the ‘stolen generations’ inquiry. Unfortunately, however, the Inquiry’s report, Bringing Them Home, is one of the most intellectually and morally irresponsible official documents produced in recent years. In this Backgrounder, Ron Brunton carefully examines a number of matters covered by the report, such as the representativeness of the cases it discussed, its comparison of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal child removals, and its claim that the removal of Aboriginal children constituted ‘genocide’. He shows how the report is fatally compromised by serious failings. Amongst many others, these failings include omitting crucial evidence, misrepresenting important sources, making assertions that are factually wrong or highly questionable, applying contradictory principles at different times so as to make the worst possible case against Australia, and confusing different circumstances under which removals occurred in order to give the impression that nearly all separations were ‘forced’. February 1998, Vol. 10/1, rrp $10.00 BETRAYING THE VICTIMS: THE ‘STOLEN GENERATIONS’ REPORT bitterness that other Australians need to comprehend INTRODUCTION and overcome. A proper recognition of the injustices that Aborigi- nes suffered is not just a matter of creating opportuni- ties for reparations, despite the emphasis that the Bring- The Inquiry and its background ing Them Home report places on monetary compensa- Bringing Them Home, the report of the National Inquiry tion (for example, pages 302–313; Recommendations into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Is- 14–20). -

Tatz MIC Castan Essay Dec 2011

Indigenous Human Rights and History: occasional papers Series Editors: Lynette Russell, Melissa Castan The editors welcome written submissions writing on issues of Indigenous human rights and history. Please send enquiries including an abstract to arts- [email protected]. ISBN 978-0-9872391-0-5 Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Indigenous Human Rights and History Vol 1(1). The essays in this series are fully refereed. Editorial committee: John Bradley, Melissa Castan, Stephen Gray, Zane Ma Rhea and Lynette Russell. Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Colin Tatz 1 CONTENTS Editor’s Acknowledgements …… 3 Editor’s introduction …… 4 The Context …… 11 Australia and the Genocide Convention …… 12 Perceptions of the Victims …… 18 Killing Members of the Group …… 22 Protection by Segregation …… 29 Forcible Child Removals — the Stolen Generations …… 36 The Politics of Amnesia — Denialism …… 44 The Politics of Apology — Admissions, Regrets and Law Suits …… 53 Eyewitness Accounts — the Killings …… 58 Eyewitness Accounts — the Child Removals …… 68 Moving On, Moving From …… 76 References …… 84 Appendix — Some Known Massacre Sites and Dates …… 100 2 Acknowledgements The Editors would like to thank Dr Stephen Gray, Associate Professor John Bradley and Dr Zane Ma Rhea for their feedback on earlier versions of this essay. Myles Russell-Cook created the design layout and desk-top publishing. Financial assistance was generously provided by the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law and the School of Journalism, Australian and Indigenous Studies. 3 Editor’s introduction This essay is the first in a new series of scholarly discussion papers published jointly by the Monash Indigenous Centre and the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law. -

Presentation Tile

Authentic and engaging artist-led Education Programs with Thomas Readett Ngarrindjeri, Arrernte peoples 1 Acknowledgement 2 Warm up: Round Robin 3 4 See image caption from slide 2. installation view: TARNANTHI featuring Mumu by Pepai Jangala Carroll, 2015, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; photo: Saul Steed. 5 What is TARNANTHI? TARNANTHI is a platform for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists from across the country to share important stories through contemporary art. TARNANTHI is a national event held annually by the Art Gallery of South Australia. Although TARNANTHI at AGSA is annual, biannually TARNANTHI turns into a city-wide festival and hosts hundreds of artists across multiple venues across Adelaide. On the year that the festival isn’t on, TARNANTHI focuses on only one feature artist or artist collective at AGSA. Jimmy Donegan, born 1940, Roma Young, born 1952, Ngaanyatjarra people, Western Australia/Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Kunmanara (Ray) Ken, 1940–2018, Brenton Ken, born 1944, Witjiti George, born 1938, Sammy Dodd, born 1946, Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara people, South Australia; Freddy Ken, born 1951, Naomi Kantjuriny, born 1944, Nyurpaya Kaika Burton, born 1940, Willy Kaika Burton, born 1941, Rupert Jack, born 1951, Adrian Intjalki, born 1943, Kunmanara (Gordon) Ingkatji, c.1930–2016, Arnie Frank, born 1960, Stanley Douglas, born 1944, Maureen Douglas, born 1966, Willy Muntjantji Martin, born 1950, Taylor Wanyima Cooper, born 1940, Noel Burton, born 1994, Kunmanara (Hector) Burton, 1937–2017, -

IPA REVIEW ESTABLISHED in 1947 by CHARLES KEMP, FOUNDING DIRECTOR of the INSTITUTE of PUBLIC AFFAIRS Vol

IPA REVIEW ESTABLISHED IN 1947 BY CHARLES KEMP, FOUNDING DIRECTOR OF THE INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS Vol. 45 No. 4,1992 Business Must Defend Itself 6 Australia, Vanuatu and the British Connection 48 Richard Craig Mark Uhlmann The current campaign against foreign-owned The view that Australia has been the pawn of British companies in Australia is misguided. foreign policy in the South Pacific is false. Bounties or Tariffs, Someone Pays 12 Millennium: Getting Tribal Rites Wrong 51 Bert Kelly Ron Brunton The cost of protection — whatever its form — must A lavish production, with a vacuous message. be borne by somebody. Menzies and the Middle Class 53 The New Constitutionalism 13 C.D. Kemp Kenneth Minogue Menzies embodied the best and the worst of his Changing constitutions is a fashionable, but `forgotten people. unreliable way of achieving political objectives. Catholicisms Condition 56 The Constitution and its Confused Critics 15 T.C. de Lacey S.E.K Hulme All is not well in the Catholic Church, but Paul Calls to update The Constitution are ill-informed. Collinss `remedies would only make things worse. Blowing the Police Whistle 20 Eric Home Whistleblowers need legislative protection. Genesis Revisited 26 From the Editor Brian J. OBrien Revolution and restraint in capitalism. In the beginning the earth was formless — then there were forms in triplicate. Moore Economics 4 Des Moore Reforming Public Sector Enterprises 30 How Victoria found itself in such a mess. Bill Scales Why its urgent and how to approach it. IPA Indicators 8 Social class figures hardly at all in Australians Delivery Postponed ^" J 34 definition of themselves. -

Early Texts and Other Sources

7 Early texts and other sources Introduction In order to demonstrate that native title has survived, the court will require that the laws and customs of the claimant society be shown not only to have survived substantially uninterrupted but also to have remained ‘traditional’1 in their content. What exactly is to be understood by the use of the term ‘traditional’ has been subject to extensive debate.2 Most, if not all, of the ethnography relevant to a native title inquiry will demonstrate the fact of some form of change. This is unsurprising since few anthropologists would argue for an unchanging society. It is the degree and measure of the change against customary systems that is subject to contestation. In short, 1 ‘A traditional law or custom is one which has been passed from generation to generation of a society, usually by word of mouth and common practice. But in the context of the Native Title Act, “traditional” carries with it two other elements in its meaning. First, it conveys an understanding of the age of the traditions: the origins of the content of the law or custom concerned are to be found in the normative rules of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies that existed before the assertion of sovereignty by the British Crown. It is only those normative rules that are “traditional” laws and customs. Second, and no less important, the reference to rights or interests in land or waters being possessed under traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the peoples concerned, requires that the normative system under which the rights and interests are possessed (the traditional laws and customs) is a system that has had a continuous existence and vitality since sovereignty. -

Black and White Children in Welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1940

‘Such a Longing’ Black and white children in welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1940 Naomi Parry PhD August 2007 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Parry First name: Naomi Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: History Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: ‘Such a longing’: Black and white children in welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1940 Abstract 350 words maximum: When the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission tabled Bringing them home, its report into the separation of indigenous children from their families, it was criticised for failing to consider Indigenous child welfare within the context of contemporary standards. Non-Indigenous people who had experienced out-of-home care also questioned why their stories were not recognised. This thesis addresses those concerns, examining the origins and history of the welfare systems of NSW and Tasmania between 1880 and 1940. Tasmania, which had no specific policies on race or Indigenous children, provides fruitful ground for comparison with NSW, which had separate welfare systems for children defined as Indigenous and non-Indigenous. This thesis draws on the records of these systems to examine the gaps between ideology and policy and practice. The development of welfare systems was uneven, but there are clear trends. In the years 1880 to 1940 non-Indigenous welfare systems placed their faith in boarding-out (fostering) as the most humane method of caring for neglected and destitute children, although institutions and juvenile apprenticeship were never supplanted by fostering. Concepts of child welfare shifted from charity to welfare; that is, from simple removal to social interventions that would assist children's reform. -

Contents 183

contents 183 Appendices 1. ABC Television Program Analysis 184 2. ABC Radio Networks Content Analysis 186 3. ABC Organisation, as at 30 June 2007 187 4. ABC Board and Board Committees 188 5. ABC Audit and Risk Committee 189 6. ABC Commercial Tax Equivalent Calculation 190 7. Consultants 191 8. Overseas Travel Costs 192 9. Reports Required Under s80 of the ABC Act 192 10. Other Required Reports 192 11. Advertising and Market Research 193 12. Occupational Health and Safety 193 13. Commonwealth Disability Strategy 196 14. Performance Pay 198 15. Staff Profile 198 16. Ecologically Sustainable Development and Environmental Performance 199 17. ABC Advisory Council 199 18. Independent Complaints Review Panel 202 19. Freedom of Information 203 20. ABC Code of Practice 2007 203 21. Performance Against Service Commitment 209 22. ABC Awards 2006–07 210 23. ABC Television Transmission Frequencies 215 APPENDICES 24. ABC Radio Transmission Frequencies 221 25. Radio Australia Frequencies 227 06–07 26. ABC Offices 228 27. ABC Shops 233 ANNUAL REPORT 20 184 Appendices for the year ended 30 June 2007 Appendix 1—ABC Television Program Analysis ABC Television Main Channel Program Hours Transmitted—24 hours Australian Overseas Total First Total First Total 2006 2005 Release Repeat Australian Release Repeat Overseas –07 –06 Arts and Culture 98 112 209 67 40 107 316 254 Children’s 76 432 508 352 1 080 1 432 1 941 2 033 Comedy 1 20 21 33 85 118 139 149 Current Affairs 807 287 1 094 0 1 1 1 095 895 Documentary 57 120 177 213 198 411 588 476 Drama 7 40 46 370 -

Report of the Select Committee on Native Title Rights in Western Australia

REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON NATIVE TITLE RIGHTS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA Presented by the Hon Tom Stephens MLC (Chairman) Report SELECT COMMITTEE ON NATIVE TITLE RIGHTS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA Date first appointed: 17 September 1997 Terms of Reference: (1) A Select Committee of five members is hereby appointed. Three members of the committee shall be appointed from among those members supporting the Government. (2) The mover be the Chairperson of the Committee. (3) The Committee be appointed to inquire into and report on — (a) the Federal Government’s proposed 10 Point Plan on native title rights and interests, and its impact and effect on land management in Western Australia; (b) the efficacy of current processes by which conflicts or disputes over access or use of land are resolved or determined; (c) alternative and improved methods by which these conflicts or disputes can be resolved, with particular reference to the relevance of the regional and local agreement model as a method for the resolution of conflict; and (d) the role that the Western Australian Government should play in resolution of conflict between parties over disputes in relation to access or use of land. (4) The Committee have the power to send for persons, papers and records and to move from place to place. (5) The Committee report to the House not later than November 27, 1997, and if the House do then stand adjourned the Committee do deliver its report to the President who shall cause the same to be printed by authority of this order. (6) Subject to the right of the Committee to hear evidence in private session where the nature of the evidence or the identity of the witness renders it desirable, the proceedings of the Committee during the hearing of evidence are open to accredited news media representatives and the public. -

Ampe-Kenhe Ahelhe

Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe COMMUNITY REPORT 2018 A Photography by Children’s Ground staff and families © All photographs, filming and recordings of Arrernte people and country is owned by Arrernte people and used by Children’s Ground with their permission. Painting ‘The Children’s Ground’ by Rod Moss, 2018 Contents Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe is the Arrernte translation for Children’s Ground. This is the name we use for 03 From our Director: MK Turner Children’s Ground in Central Australia. Mparntwe is the Arrernte word for the area in and around Alice Springs. 04 Ingkerrekele Arntarnte-areme | Everyone Being Responsible (Governance) 05 Anwerne-kenhe Angkentye, Iterrentye | Our Principles 07 From our Chairperson: William Tilmouth 08 From our Directors: The Story So Far 10 Ampe Mape Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe | Children’s Ground Children 2018 12 Ampe Akweke Mape-kenhe Ayeye | Children’s Stories 18 Akaltye-irreme Unte Mwerre Anetyeke | Learning and Wellbeing 20 Anwerne Ingkerreke Apurte Urrkapeme | Working Side by Side 22 Arrernte-kenhe Angkentye | Arrernte Curriculum 23–29 Akaltye-irreme Apmerele | Learning on Country 30 Tyerrtye Mwerre Anetyeke | Health and Wellbeing 32 Mwerrentye Warrke Irretyeke | Economic Development and Wellbeing 36 Arne Mpwaretyeke, Mwantyele Antirrkwetyke | Creative Development and Wellbeing 42 Tyerrtye Areye Mwerre Anetyeke | Community Development and Wellbeing 44 Ayeye Anwerne-kenhe ileme | Sharing Our Story 46 Anwerne ingkerreke Apurte Irretyeke | Reconciliation Week 2018: We All Get Together 50 Ampe Anwernekenhe Rlterrke Ingkerre Atnyenetyeke | Keeping All Our Children Strong 51 Kele Mwerre | Thank you 52 Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe Staff 2018 1 “Anwerne Ampe-kenhe Ahelhe-nge warrke mwerre anthurre mpwareke year- nhengenge. -

Meteoritics and Cosmology Among the Aboriginal Cultures of Central Australia

Journal of Cosmology, Volume 13, pp. 3743-3753 (2011) Meteoritics and Cosmology Among the Aboriginal Cultures of Central Australia Duane W. Hamacher Department of Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University, NSW, 2109, Australia [email protected] Abstract The night sky played an important role in the social structure, oral traditions, and cosmology of the Arrernte and Luritja Aboriginal cultures of Central Australia. A component of this cosmology relates to meteors, meteorites, and impact craters. This paper discusses the role of meteoritic phenomena in Arrernte and Luritja cosmology, showing not only that these groups incorporated this phenomenon in their cultural traditions, but that their oral traditions regarding the relationship between meteors, meteorites and impact structures suggests the Arrernte and Luritja understood that they are directly related. Note to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Readers This paper contains the names of, and references to, people that have passed away and references the book “Nomads of the Australian Desert” by Charles P. Mountford (1976), which was banned for sale in the Northern Territory as it contained secret information about the Pitjantjatjara. No information from the Pitjantjatjara in that book is contained in this paper. 1.0 Introduction Creation stories are the core of cosmological knowledge of cultures around the globe. To most groups of people, the origins of the land, sea, sky, flora, fauna, and people are formed by various mechanisms from deities or beings at some point in the distant past. Among the more than 400 Aboriginal language groups of Australia (Walsh, 1991) that have inhabited the continent for at least 45,000 years (O’Connell & Allen, 2004) thread strong oral traditions that describe the origins of the world, the people, and the laws and social structure on which the community is founded, commonly referred to as “The Dreaming” (Dean, 1996).