Report of the Select Committee on Native Title Rights in Western Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional Recognition Relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Submission 394 - Attachment 1

Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Submission 394 - Attachment 1 Attachment 1 - Timeline and Overview of findings Australian Human Rights Commission Submission to the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples – July 2018 Event Summary of event / response of Social Justice Commissioner 1991 The Royal Commission Both reports state an ongoing historical connection between past racist into Aboriginal Deaths in policies and legislation and current systemic discrimination and intersecting Custody (RCIADIC) issues of disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal and Torre Strait Islander releases its report peoples. Human Rights and Equal NIRV states that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience an Opportunity Commission's endemic racism, causing serious racial violence associated with structural (HREOC) National Inquiry discrimination across Australian society. into Racist Violence (NIRV) releases its report The RCIADIC puts forward 339 recommendations. This includes developing pathways to achieving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander self- determination, and the critical need to progress reconciliation to achieve the systemic changes recommended in the report.1 The Council of Aboriginal The Act states that CAR has been established because: Reconciliation (CAR) is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples occupied Australia before established under the British settlement at Sydney Cove -

Native Title Act 1993

Legal Compliance Education and Awareness Native Title Act 1993 (Commonwealth) Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) How does the Act apply to the University? • On occasion, the University assists with Native Title claims, by undertaking research & producing reports • Work is undertaken in conjunction with ARI, Native Title representative bodies & claims groups • Representative bodies define the University’s obligations & responsibilities with respect to Intellectual Property, ethics, confidentiality & cultural respect • While these obligations are contractual, as opposed to legislative, the University would be prudent to have an understanding of the Native Title Act, how a determination of Native Title is made & the role that the Federal Court has in the management of all applications made under the Act University of Adelaide 2 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) A brief history of Native Title: Pre -colonisation • Aboriginal people & Torres Strait Islanders occupied Australia for at least 40,000 to 60,000 years before the first British colony was established in Australia • Traditional laws & customs were characterised by a strong spiritual connection to 'country' & covered things like: – caring for the natural environment and for places of significance – performing ceremonies & rituals – collecting food by hunting, fishing & gathering – providing education & passing on law & custom through stories, art, song & dance • In 1788 the British claimed sovereignty over part of Australia & established a colony University of Adelaide 3 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) A brief history of Native Title: Post-colonisation • In 1889, the British courts applied the doctrine of terra nullius to Australia, finding that as a territory that was “practically unoccupied” • In 1979, the High Court of Australia determined that Australia was indeed a territory which, “by European standards, had no civilised inhabitants or settled law” 1992 – The Mabo decision • The Mabo v Queensland (No. -

Western Australia

115°0'E 120°0'E 125°0'E Application/Determination boundaries compiled by NNTT based on data Native Title Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 sourced from and used with the permission of DLP (NT), The applications shown on the map include: While the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) and the Native Title Registrar DoR (NT), DNRM (Qld) and Landgate (WA). © The State of Queensland - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration (Registrar) have exercised due care in ensuring the accuracy of the information (DNRM) for that portion where their data has been used. test), provided, it is provided for general information only and on the understanding Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, that neither the NNTT, the Registrar nor the Commonwealth of Australia is Australia) 2003. - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for providing professional advice. Appropriate professional advice relevant to your Coastline/state borders (1998) data and Towns (1997) sourced from registration), circumstances should be sought rather than relying on the information Geoscience Australia (1998). - non-claimant and compensation applications. provided. In addition, you must exercise your own judgment and carefully Western Australia As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all Determinations shown on the map include: evaluate the information provided for accuracy, currency, completeness and applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. - registered determinations as per the National Native Title Register (NNTR), relevance for the purpose for which it is to be used. -

NDP Recall Defence Faces Probe Busy Lin Es Block Ambulance Calls

Free speech Time to celebrate The champions What do pepper sprayed protes- North Coast Distance Education A penalty shot and a couple of ters have to do with a Terrace School marks 10 years with an yellow cards prove decisive in aviation company?\NEWS A:I.3 open housekCOMMUNrrY B1 men's soccer finals\SPORTS B6 93¢ PLUS 7¢ GST WEDNESDAY SEPTEMBE.R 23, 1998 TANDA.RD VOL. 11 NO. 24 NDP recall defence faces probe A 'covert operation' including 'dirty tricks'? Or a textbook well-organized political campaign? By JEFF NAGEL "fake" "letters to the editors prepared for "It was a campaign just like any other ray confirmed. SKEENA MLA Helmut Giesbrecht~is distribution to local papers as part of a campaign," Murray said. "We tackled this McPhee's presence for two weeks was rejecting suggestions his supporters did "dirty tricks" campaign. just like we would an election. This is the reported in news stories by the Standard as anything wrong in defending him "It's a load of crap," Giesbrecht said only way we know how to do a political early as Dec. 23. Murray says had she been against a recall campaign last winter. Thursday. "It's the biggest crock of horse fight ~ an organized campaign." a secret, covert operative, an interview Elections B.C. on Friday appointed foren- manure I've heard in a long time." "But this time we didn't just out-organize would not have been granted. sic auditor Ron Parks to investigate recall "There was no covert operation. There them, they didn't have the support they Both workers were paid and their salaries campaigns here, in Prince George and were no dirty tricks. -

Seniors Housing Effort Revived THERE's RENEWED Optimism a Long-Sought Plan for a Crnment in 1991

Report card time He was a fighter Bring it onl We grade Terrace's city council on The city mourns the loss of one of how it rode out the ups and The Terrace Soirit Riders play hard its Iongtime activists for social downs of 2000\NEWS A5 and tough en route to the All- I change\COMMUNITYB1 Native\SPORTS B5 1 VOL. 13 NO. 41 WEDNESDAY m January 17, 2001 L- ,,,,v,,..~.,'~j~ t.~ilf~. K.t.m~ $1.00 PLUS 7¢ GST ($1.10 plus 8t GST outside of the Terracearea) TAN DARD ,| u Seniors housing effort revived THERE'S RENEWED optimism a long-sought plan for a crnment in 1991. construction. different kind of seniors housing here will actually hap- pen. Back then Dave Parker, the Social Credit MLA for The project collapsed at that point but did begin a re- Officials of the Terrace and Area Health Council Skeena, was able to have the land beside Terraceview Lodge tui'ned over by the provincial government to the vival when the health council got involved. have been meeting with provincial housing officials .to It already operates Terraceview Lodge so having it build 25 units of rental housing on land immediately ad- Terrace Health Care Society, the predecessor of the health council. also be responsible for supportive housing made sense, jacent to Terraceview Lodge. said Kelly. This type of accommodation is called supportive Several attempts to attract government support through the Dr. R.E.M. Lee Hospital Foundation failed. This time, all of the units will be rental ones, he housing in that while people can. -

MINUTES of the REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING HELD in the MUNICIPAL COUNCIL CHAMBERS on MONDAY, JANUARY 9Th, 1995, at 7:30 P.M

MINUTES OF THE REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING HELD IN THE MUNICIPAL COUNCIL CHAMBERS ON MONDAY, JANUARY 9th, 1995, AT 7:30 P.M. Mayor J. Talstra presided. Councillors present were E. Graydon, R. Hallock, V. George, D. Hull, G. Hull and R. McDaniel. Also in attendance were E.R. Hallsor, Clerk-Administrator and J. Wakaruk, Confidential Secretary. ADDENDUM: There was no Addendum. DELEGATIONS & GUESTS: Mr. Sullivan, representing Lockport Security Ltd., presented to Council a report by CANASA (Canadian Joe Sullivan - Alarm and Security Association) and Lockport Security Lockport Security Ltd. Ltd. entitled "Intrusion Alarm Systems and Bylaws". Mr. Sullivan expressed his concerns over the City's present Security Alarms Systems Regulation Bylaw, whereby alarm owners are fined for excessive false alarms, and requested that Council consider the proposal presented to them as an alternative form of addressing this issue. Mayor Talstra thanked Mr. Sullivan for his presentation, and advised that his matter would be dealt with as the last item under the "Correspondence" portion of this meeting's Agenda. PETITIONS & QUESTIONS: There were none. MINUTES: MOVED by Councillors G. Hull/D. Hull that the Regular Council Minutes, December 12, 1994, Regular Council Minutes be December 12, 1994 adopted as circulated. (No. 001) Carried. Special Council Meeting, MOVED by Councillors Graydon/McDaniel that the December 19, 1994 December 19, 1994, Special Council Minutes be adopted as circulated. (No. 002) Carried. Reg. Council, January 9, 1995 Page 2 BUSINESS ARISING FROM MOVED by Councillors Graydon/D. Hull that the City THE MINUTES (OLD BUSINESS): of Terrace study and implementation of a hiring freeze and, in light of privatization, Council take a more active Tabled Motion No. -

From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 19 Access to Justice: The Social Responsibility of Lawyers | Contemporary and Comparative Perspectives on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples January 2005 From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia Lisa Strelein Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa Strelein, From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia, 19 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 225 (2005), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol19/iss1/14 This Rights of Indigenous Peoples - Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia Dr. Lisa Strelein* INTRODUCTION In more than a decade since Mabo v. Queensland II’s1 recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights to their traditional lands, the jurisprudence of native title has undergone significant development. The High Court of Australia decisions in Ward2 and Yorta Yorta3 in 2002 sought to clarify the nature of native title and its place within Australian property law, and within the legal system more generally. Since these decisions, lower courts have had time to apply them to native title issues across the country. This Article briefly examines the history of the doctrine of discovery in Australia as a background to the delayed recognition of Indigenous rights in lands and resources. -

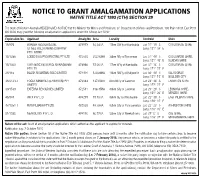

Notice to Grant Amalgamation Applications 5

attendance and improve peer relationships • Engage with families of young people involved in workshops • Maintain statistical records and data on service delivery Applications can be lodged online at • Program runs for up to 12 months Applications Now Open liveandworkhnehealth.com.au/work/ POSITION VACANT Desirable Criteria: Apply now to be part of the exciting first NSW Public opportunities-for-aboriginal-torres-strait-islander-people/ • Ability to connect and engage with young Application Information Packages are available Aboriginal and Torres Strait Service Talent Pools. people at this web address or by contacting Islander Workshop Successfully applying for a talent pool is a great way to the application kit line on (02) 4985 3150. • Experience in conducting workshops namely in be considered for a large number of roles across the Facilitator school settings • Recognised tertiary qualifications in working NSW Public Service by submitting only one application. Ward Clerk Part-Time (3 days a week, 6 hours a day) The role: with young people Administrative Support Officer Muswellbrook • Skills in delivering innovative and artistic • To provide cultural workshops with one other – Open 16 to 29 September 2015 Enquires: Dianne Prangley, (02) 6542 2042 workshops through diverse cultural and artistic Policy Officer facilitator in local schools (Mt Druitt) expression Reference ID: 279881 • Workshops aim are to engage with students – Open 28 September to 12 October 2015 To apply please send your resume by Sunday 20th Applications may close early should 500 applications and improve identification with Aboriginal Closing Date: 14 October 2015 September to: [email protected] phone Julie be received culture; involve young people in NAIDOC week celebrations, increase school retention Dubuc on 0404 087 416. -

Review of the Native Title Act 1993

Review of the Native Title Act 1993 DISCUSSION PAPER You are invited to provide a submission or comment on this Discussion Paper Discussion Paper 82 (DP 82) October 2014 This Discussion Paper reflects the law as at 1st October 2014 The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) was established on 1 January 1975 by the Law Reform Commission Act 1973 (Cth) and reconstituted by the Australian Law Reform Commission Act 1996 (Cth). The office of the ALRC is at Level 40 MLC Centre, 19 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000 Australia. Postal Address: GPO Box 3708 Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone: within Australia (02) 8238 6333 International: +61 2 8238 6333 Facsimile: within Australia (02) 8238 6363 International: +61 2 8238 6363 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.alrc.gov.au ALRC publications are available to view or download free of charge on the ALRC website: www.alrc.gov.au/publications. If you require assistance, please contact the ALRC. ISBN: 978-0-9924069-6-7 Commission Reference: ALRC Discussion Paper 82, 2014 © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in whole or part, subject to acknowledgement of the source, for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation. Requests for further authorisation should be directed to the ALRC. Making a submission Any public contribution to an inquiry is called a submission. The Australian Law Reform Commission seeks submissions from a broad cross-section of the community, as well as from those with a special interest in a particular inquiry. -

FIGHTING OVER COUNTRY: Anthropological Perspectives

FIGHTING OVER COUNTRY: Anthropological Perspectives Edited by D.E. Smith and J. Finlayson Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research The Australian National University, Canberra Research Monograph No. 12 1997 First published in Australia 1997. Printed by Instant Colour Press, Canberra, Australia. © Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University. This book is copyright Apart from any fair dealings for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia. National Library of Australia. Cataloguing-in-publication entry. Fighting over country: anthropological perspectives ISBN 07315 2561 2. 1. Aborigines, Australian - Land tenure. 2. Native title - Australia. 3. Torres Strait Islanders - Land tenure. 4. Land use - Australia. I. Finlayson, Julie, n. Smith, Diane (Diane Evelyn). ID. The Australian National University. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. (Series: Research monograph (The Australian National University. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research); no. 12). 306.320899915 Acknowledgments A number of people assisted in the organisation and conduct of the workshop Fighting Over Country: Anthropological Perspectives held in Canberra in late September 1996. The workshop was the latest in a series sponsored by the Australian Anthropological Society focusing on land rights and native title issues. Diane Smith, Julie Finlayson, Francesca Merlan, Mary Edmunds and David Trigger formed the organising committee, and ongoing administrative support was provided by the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR). The Native Titles Research Unit of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) provided modest but very helpful financial assistance towards catering for the workshop. -

SCOTUS and the Origins of Australia's Scabrous Constitutional Signature Benjamen Franklen Guss

Br. J. Am. Leg. Studies 10(1) (2021), DOI: 10.2478/bjals-2021-0001 The Engineers Case Centenary: SCOTUS and the Origins of Australia’s Scabrous Constitutional Signature Benjamen Franklen Gussen* Sahar Araghi** ABSTRACT Since the Engineers Case decision in 1920, the role of the United States Constitution in interpreting the Australian Constitution has been diminished, leading to inefficiencies in High Court of Australia (HCA) dealing with constitutional issues. To explain this thesis, the article looks at the 7,657 cases decided by the HCA, from the first case in 1903, to the 31st of August 2020, the centenary of the Engineers Case. The analysis identifies outliers that have much higher complexity (in terms of word- length) than the other judgments. This complexity has one common denominator: comparative analysis with the United States Constitution. The article explains why this common denominator has resulted in such complexity, and concludes with possible research extensions on the roles of the Australian judiciary in embracing SCOTUS jurisprudence when interpreting the Australian Constitution. KEYWORDS High Court of Australia (HCA), Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), The Engineers Case, Constitutional Signature, Complexity CONTENTS I. Introduction ....................................................................................... 29 II. Overview of High Court Cases 1903-2020 ...................................... 31 III. First Tier Outliers .......................................................................... 33 1 -

Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal Languages South of the Kimberley Region

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - 124 HANDBOOK OF WESTERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES SOUTH OF THE KIMBERLEY REGION Nicholas Thieberger Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Thieberger, N. Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley Region. C-124, viii + 416 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1993. DOI:10.15144/PL-C124.cover ©1993 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES c: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W.Bender KA. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics DavidBradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University University of Adelaide S.H. Elbert G.N. O'Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Franklin KL. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W.Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W.Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K T' sou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. Uhlenbeck Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Leiden L.A.