Toll Roads and Airport Projects As Their Request for Proposal (RFP) Processes Are in a More Advanced Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Advanced Manufacturing and Sustainable Innovation: the Third

Advanced Manufacturing and Sustainable Innovation: The Third Wave of Industrial and Urban Economic Growth for Minas Gerais A Report to the Federation of Industries of Minas Gerais (FIEMG) by Global Urban Development (GUD) October 2012 Executive Summary Minas Gerais has succeeded in its first century‐long wave of economic growth through industrialization and urbanization, made great strides over the past decade in the second wave of economic growth through rising incomes and growing consumer demand, and is now poised for a third wave of globally competitive prosperity and productivity driven by Sustainable Innovation. Minas Gerais already has developed several new Sustainable Innovation Pipelines, from biomedical to information technology. The next great surge for the Third Wave, the newest and most dynamic and productive Sustainable Innovation Pipeline for Minas Gerais, will be in Advanced Manufacturing. Brazil can compete directly with Advanced Manufacturing public policies and private companies throughout the world; and Minas Gerais can become one of Brazil’s national leaders in this rapidly growing industrial technology field. 1 GUD recommends that FIEMG collaborate with CETEC and SENAI, focusing on the CETEC and its surrounding area, including Carlos Prates Airport, as a key anchor for a statewide Advanced Manufacturing Sustainable Innovation Strategy, to be implemented through the six key initiatives: 1) Advanced Manufacturing Sustainable Innovation Center 2) Advanced Manufacturing Business Accelerator 3) Advanced Manufacturing Technology Industrial Park 4) Advanced Manufacturing Business Advisory Services 5) Advanced Manufacturing Skills Training 6) Advanced Manufacturing Sustainable Innovation Zone In the following pages, GUD provides a detailed explanation of the possibilities and opportunities of an Advanced Manufacturing Sustainable Innovation Strategy; an overview of the strategic implementation framework for each of the six key initiatives; and numerous international best practices and other major examples. -

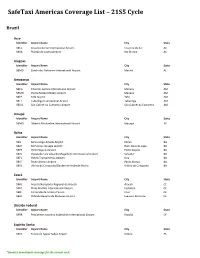

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

Relatório Social Infraero | 2004 Infraero Social Report

Relatório Social Infraero | 2004 Infraero Social Report 1 MENSAGEM DO PRESIDENTE Infraero atingiu, em 2004, sua meta social de desenvolver A pelo menos um projeto em todos os aeroportos que adminis- tra, um marco histórico para a empresa que registramos neste relatório. São 67 ações que atendem a mais de 21 mil pessoas em todo o Brasil. Números inexpressivos em relação ao que gostarí- amos de fazer e às necessidades do país, mas bastante relevantes ao refletirem o engajamento dos funcionários da empresa, aos quais gostaria de agradecer e dedicar este feito. Por trás de cada ação, há a atuação obstinada de funcionários da Infraero, que se dispõem a estender suas jornadas de trabalho num terceiro expediente, em sábados e domingos para ajudar pessoas que sequer conhecem. Abstêm-se do convívio com as suas famílias para se dedicarem a outras, cujas vidas de priva- ção acompanham da janela do escritório sem nunca se acostu- marem ou se conformarem. Um trabalho desinteressado, cuja única gratificação está na esperança de poder contribuir para a construção de uma sociedade mais justa e igualitária. Esta é a principal semente do Programa Infraero Social, desen- volver a solidariedade e fomentar o inconformismo com qual- quer tipo de pobreza e desigualdade. É mostrar que a Infraero não é feita apenas de concreto. É feita de pessoas e, principal- mente, de corações. Carlos Wilson Campos MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT nfraero achieved, in 2004, its social goal of developing at Ileast one project in all the airports that it manages, a historic landmark for the company that we record in this report. -

Gen 0.1-1 Brasil 25 Jun 15

AIP GEN 0.1-1 BRASIL 25 JUN 15 PART 1 – GENERAL (GEN) GEN 0.1 PREFACE 1. NAME OF PUBLISHING AUTHORITY The Director of the Department of Airspace Control (DECEA) is responsible for the publication of the AIP Brasil. 2. APPLICABLE ICAO DOCUMENTS The AIP is prepared in accordance with the Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPS) of Annex 15 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation and the Aeronautical Information Services Manual (ICAO Doc. 8126). Charts included in the AIP are produced in accordance with Annex 4 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation and the Aeronautical Chart Manual (ICAO Doc. 8697). Differences from ICAO Standards, Recommended Practices and Procedures are given in subsection GEN 1.7 3. PUBLICATION MEDIA Printed and online 4. THE AIP STRUCTURE AND ESTABLISHED REGULAR AMENDMENT INTERVAL 4.1 The AIP structure The AIP forms part of the integrated aeronautical package, details of which are given in subsection GEN 3.1. The principal AIP structure is shown in graphic form on page GEN 0.1-3. The AIP is made up of three parts, General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD), each divided into sections and subsections as applicable, containing various types of information subjects. 4.1.1 Part 1 - General (GEN) Part 1 consists of five sections containing information as briefly described hereafter: GEN 0. Preface, record of AIP amendments, record of AIP supplements, checklist, list of hand amendments and the table of contents to Part 1. GEN 1. National regulations and requirements – Designated authorities; entry, transit and departure of aircraft; entry, transit and departure of passengers and crew; entry, transit and departure of cargo; aircraft instruments, equipment and flight documents; summary of national regulations and international agreements/conventions; and differences from ICAO standards, recommended practices and procedures. -

Minha Historia Do Brasil (My Story of Brazil)

Minha Historia do Brasil (My Story of Brazil) 1 Table of Contents • Prologue -- 3 • Introduction -- 4 • The Brazil Experience -- 5 • The Biotechnology Lab and Embrapa Soja – 8 • The Supervised Practical Training -- 10 • Brazil and World Food Security -- 17 • Epilogue -- 19 • Acknowledgments -- 21 • Appendix 1 – 22 • Appendix 2 -- 23 • References – 24 • Photos -- 25 2 Prologue “Is that all? Can we just leave now?” “I think so...” came the reply. I was asking two Mormon missionaries just outside the customs inspection in the São Paulo International Airport, engaging in what would be my final conversation with Americans for eight weeks. I had just gotten off the plane after a sleepless night and felt tired, excited, and very confused at the same time as I just passed inspection. From what my parents and other sources told me, long lines and intensive baggage verification was routine; however, I was able to pass through in about a minute without a second glance. “But isn't Customs supposed to be a bit more careful and need to inspect my luggage?” I asked the missionaries again. One of the missionaries put his hand on chin in the thinker pose. “hmmm... you're right.” He said thoughtfully, “But after all, this is Brazil...” This is Brazil... all of the sudden it hit me. For the next two months, this was home. Unlike home though, I did not have the slightest idea what or who I would find in this place. I immediately had second thoughts. What am I doing in this country? I had an internship here in an unknown lab, but I didn't have any lab experience or communication skills in a different language. -

Iowa's Parallel to Brazil

Soja: Iowa’s Parallel to Brazil Alyssa Beatty Chariton, Iowa 2006 Borlaug-Ruan Intern: June 13th – August 10th, 2006 Embrapa Soja Londrina, Brazil A. Beatty 2 OUTLINE I. Acknowledgments II. Background Information A. Brazil B. Embrapa Soja III. Introduction A. Me & WFP Foundation B. Getting to Brazil C. First Impressions IV. Procedures and Methodology A. Biological Control B. DNA Extraction C. PCR & Agarose Gels V. Observations A. Biological Control B. DNA Extraction C. PCR & Agarose Gels VI. Conclusion VII. Works Cited VIII. Appendix A. Beatty 3 I. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank Norman E. Borlaug and John Ruan for making the Internship Program a reality; it makes incredible experiences available for students. The things I have learned and people I have met will forever be instilled in my memory. Secondly, Lisa Fleming’s personal, motivational, and organizational skills helped me to live in Brazil for two months. If not for her constant devotion to the Youth Programs of the World Food Prize Foundation, the Youth Institute and Internship Program would be missing out on a truly amazing person. Dr. Daniel Ricardo Sosa-Gómez acted as my supervisor during my internship at Embrapa Soja. I am eternally grateful for his vast scientific knowledge and guidance. The Laboratory of Biotechnology and Bioinformatics and its employees were a second family and allowed me to learn and work with them for two months. I especially thank Danielle Cristina Gregório Da Silva for her friendship and direction; she will always remain my friend. The opportunity to live with a Brazilian family allowed me to experience the culture first-hand. -

TERRADERIQUEZAS3 Rq7xxtb

LONDRINA TERRA DE RIQUEZAS III LAND OF WEALTH III P E R F I L I N S T I T U C I O N A L Apresentação.........................................................................................................................................09 Londrina em Desenvolvimento..........................................................................................................10 Desenvolvimento Humano.................................................................................................................12 Entre as melhores do País...................................................................................................................15 Qualidade de Vida.................................................................................................................................16 Educação.................................................................................................................................................18 Saúde.......................................................................................................................................................22 Parque Industrial...................................................................................................................................26 Parque Tecnológico..............................................................................................................................29 Atividades Instaladas em Londrina...................................................................................................30 Indústria..................................................................................................................................................32 -

AUCTION No. 01/2020 CONCESSION for the EXPANSION

AUCTION No. 01/2020 CONCESSION FOR THE EXPANSION, MAINTENANCE AND EXPLORATION OF AIRPORTS INTEGRATING IN THE SOUTH, CENTRAL AND NORTHERN BLOCKS 1 Sumário PREAMBLE ..................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER I - INITIAL PROVISIONS .................................................................................................. 5 Section I - Definitions ................................................................................................................ 5 Section II - Object .................................................................................................................... 11 Section III - Access to the Public Notice .................................................................................. 13 Section IV - Clarifications on the Notice .................................................................................. 14 Section V - Technical Visits ...................................................................................................... 14 Section VI - From the Challenge to the Notice ........................................................................ 15 Section VII - General Provisions .............................................................................................. 15 CHAPTER II - THE SPECIAL BIDDING COMMITTEE ....................................................................... 17 CHAPTER III - PARTICIPATION IN THE AUCTION ......................................................................... -

20-F 1 Tamform20f2010.Htm FORM 20-F

20-F 1 tamform20f2010.htm FORM 20-F As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on May 13, 2011 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ⌧ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2010 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number 333-131938 Commission file number Commission file number 333-145838-02 333-145838-01 TAM S.A. TAM Capital Inc. TAM Linhas Aéreas S.A. (Exact name of registrant as specified (Exact name of registrant as (Exact name of registrant as in its charter) specified in its charter) specified in its charter) Not applicable Not applicable TAM Airlines S.A. (Translation of registrant name into (Translation of registrant name into (Translation of registrant name into English) English) English) The Federative Republic of Brazil Cayman Islands The Federative Republic of Brazil (State or other jurisdiction of (State or other jurisdiction of (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) incorporation or organization) incorporation or organization) 4512 4512 4512 (Primary Standard Industrial (Primary Standard Industrial (Primary Standard Industrial Classification Code Number) Classification Code Number) Classification Code Number) Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable (I.R.S. Employer Identification (I.R.S. -

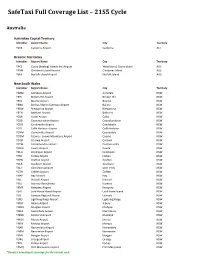

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

BRAZIL Study 1

SOUND DIPLOMACY IS THE LEADING GLOBAL MUSIC EXPORT AGENCY Sound Diplomacy is a multi‑lingual export, research and event production consultancy based in CONSULTING London, Barcelona and Berlin. Export Strategizing We draw on over thirty years of Planning & Development creative industries experience Brand Management to deliver event and conference Workshop Coordination coordination, world‑class research, Market Research export strategy and market & Analysis intelligence to both the public and Teaching & Strategic private sector. Consulting We have over 30 clients in 4 continents, including government ministries, music and cultural EVENT export offices, music festivals and SERVICES conferences, universities and more. Conference We work simultaneously in seven Management languages (English, Spanish, Event Production Catalan, German, French, Greek, Coordination Danish). & Logistics SOUND DIPLOMACY ACTIVE EVENTS BRAZIL STUDY 1. INTRODUCTION THIS RESEARCH AIMS TO IDENTIFY HOW THE 1.1. WORLD MUSIC CONCEPT MUSIC BUSINESS AND MARKET WORKS IN BRAZIL, SPECIFICALLY IN THE CASE OF WORLD MUSIC. THIS IS IN ORDER TO UNDERSTAND AND LEARN ABOUT The complexity starts with the very concept of “World THE EXISTENCE OF MUSIC FESTIVALS, VENUES AND Music” (Música do Mundo - in Portuguese). There is no CULTURAL CENTRES THAT MIGHT BE SUITABLE clear definition, even among music professionals, about FOR INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS, AS WELL AS PUBLIC what is actually considered world music in Brazil. For OPENNESS AND INTEREST, AND THE SPACE AND some, it represents everything that is not sung in English, ATTENTION GIVEN BY THE MEDIA TO THESE FORMS OF or which comes from the United States or the UK, or is MUSIC FROM ABROAD. not rock, pop or jazz; but overall, it is felt that the term does not help to understand what kind of music is being talked about, and some find that it can carry even a Programmers, producers, journalists and consultants prejudiced perspective. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Alter-Worlds Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Alter-Worlds of Lispector and Saer and the End(s) of Latin American literature A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature By Peter James Lehman 2013 © Copyright 2013 Peter James Lehman ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Alter-Worlds of Lispector and Saer and the End(s) of Latin American Literature By Peter James Lehman Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Randal Johnson, Co-chair Professor Kirstie McClure, Co-chair My dissertation seeks to intervene in current debates about both comparative perspectives within Latin American literatures and the place of Latin America within new models of world literature. Despite the importance of this call to a more planetary approach to literature, the turn to a world scope often recapitulates problems associated with the nineteenth century emergence of the term “world literature”: local concerns and traditions dissolve into the search for general patterns or persistent dependencies. If these new comparative models tend to separate the local from the construction of literature’s “world,” significant strains of Latin Americanist criticism have also sought to distance the local from literature and the literary, often identifying the latter alternatively with either the collapse of previous emancipatory dreams or a complicity with power and domination. Focusing on several central narrative texts of the Brazilian Clarice ! ii! Lispector and the Argentine Juan José Saer, I argue for a more contested notion of both the literary and the world. Both Lispector’s and Saer’s pairs of narrative texts in this dissertation make it difficult to untangle the literary construction of their respective worlds from local forms of alterity and otherness.