Report on Samoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Resolution Bathymetric Survey of Samoa

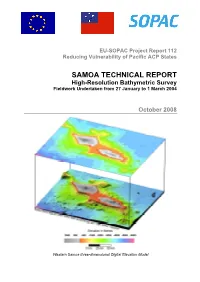

EU-SOPAC Project Report 112 Reducing Vulnerability of Pacific ACP States SAMOA TECHNICAL REPORT High-Resolution Bathymetric Survey Fieldwork Undertaken from 27 January to 1 March 2004 October 2008 Western Samoa three-dimensional Digital Elevation Model Prepared by: Jens Krüger and Salesh Kumar SOPAC Secretariat May 2008 PACIFIC ISLANDS APPLIED GEOSCIENCE COMMISSION c/o SOPAC Secretariat Private Mail Bag GPO, Suva FIJI ISLANDS http://www.sopac.org Phone: +679 338 1377 Fax: +679 337 0040 www.sopac.org [email protected] Important Notice This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Community; however, the views expressed herein must never be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Community. Samoa: High-Resolution Bathymetry EU EDF-SOPAC Reducing Vulnerability of Pacific ACP States – iii TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Geographic Situation .................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Geological Setting ...................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Previous Bathymetry Compilations............................................................................ -

Apolima Strait −13˚12' Samoa

Apolima Strait −13˚12' Samoa −13˚24' Fagamalo Asau Harbour Entrance Cape Mulinu’u −13˚36' Faga Sala’ilua Salelologa Passage Satupaitea Aganoa −13˚48' Apolima Strait Apia Harbour Entrance Mulifanua Warf Fugro Wave Buoy 1 −14˚00' Safata Bay Salani Fugro Wave Buoy 2 Nu’usafe’e Bay Cape Tapaga −14˚12' −173˚00' −172˚48' −172˚36' −172˚24' −172˚12' −172˚00' −171˚48' −171˚36' −171˚24' −171˚12' Figure 1. Location maps of the site. The map on the left shows the region. The map on the right shows the island and its surroundings. The red point shows to the actual site and green points (if present) indicate other available wave climate reports in the region. A copy of this report is available at http://gsd.spc.int/wacop/ I. General Wave Climate I.1 General Introduction This wave climate report presents wave information for Apolima Strait in Samoa. This report contains information about wind−generated surface gravity waves, often called wind waves and swell. The wave climate is defined here as the statistics of waves conditions over a 30 year period. The report details the average wave condition (page 2 and 3), the variability of wave conditions (page 4 and 5), severe and extreme waves (page 6 to 9) and characterises the wave energy resource(Page 10). Similar wave climate reports are available for more than 80 locations around the Pacific, near important ports, large settlements, tide gauge locations and areas where the wave climate is of particular interest. Other locations in Samoa are shown in Figure 1 (Previous page). -

Mavae and Tofiga

Mavae and Tofiga Spatial Exposition of the Samoan Cosmogony and Architecture Albert L. Refiti A thesis submitted to� The Auckland University of Technology �In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art & Design� Faculty of Design & Creative Technologies 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... i Attestation of Authorship ...................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ viii Abstract .................................................................................................................................... ix Preface ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Leai ni tusiga ata: There are to be no drawings ............................................................. 1 2. Tautuanaga: Rememberance and service ....................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6 Spacing .................................................................................................................................. -

2.1.4 Samoa Port of Mulifanua

2.1.4 Samoa Port of Mulifanua Port Overview Mulifanua is a village on the north-western tip of the island of Upolu. Mulifanua wharf is the main ferry terminal for inter-island vehicle and passenger travel across the Apolima Strait between Upolu and the island of Savai'i. The government's joint venture company Samoa Shipping Corporation (SSC) operates the ferry service, seven days a week, between Mulifanua and Salelologa at the east end of Savai'i Island. A one-way trip between the two islands takes about 90 minutes. The ferry usually runs every two hours during the day. SSC is also responsible for management of the port . The port is utilised solely as a ferry terminal, and as such there are no facilities at the port other than a passenger terminal, ticket office and roll on roll off wharf. In 2018 Mulifanau had an upgrade completed on the passenger and bus terminal. As a result of drifting sand, dredging operation is being planned to maintain channel width and depth. Port website: http://www.samoashipping.com/destinations/mulifanua Key port information may also be found at: http://www.maritime-database.com Port Location and Contact Country Samoa Province or District Upolu Island, Aiga-i-le-Tai district Nearest Town or City Mulifanau with Distance from Port (Village at the port) Port's Complete Name Port of Mulifanau Latitude -13.830154 Longitude -172.036398 Managing Company or Port Authority Samoa Shipping Company Management Contact Person Pipi Ioane Fomai ([email protected]) Nearest Airport and Airlines with Frequent International Arrivals/Departures Faleolo International Airport Air NZ, Virgin Australia, Samoa Airlines. -

Sustainable Urban Mobility in South-Eastern Asia and the Pacific

Sustainable Urban Mobility in South-Eastern Asia and the Pacific Hoong-Chor Chin Regional study prepared for Global Report on Human Settlements 2013 Available from http://www.unhabitat.org/grhs/2013 Hoong-Chor Chin is an Associate Professor and Director of Safety Studies Initiative at the Dept of Civil and Environmental Engineering, National University of Singapore. A Professional Engineer, he has undertaken numerous consultancy and research work on Transportation Planning, Traffic Modelling and Road Safety Studies for local authorities and developers as well as organizations such as Asian Development Bank and Cities Development Initiative for Asia. Comments can be sent to: [email protected]. Disclaimer: This case study is published as submitted by the consultant, and it has not been edited by the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the Governing Council of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme or its Member States. Nairobi, 2011 Contents 1. The Crisis of Sustainability in Urban Mobility: The Case of South-Eastern -

Climate of Samoa

DaDatata CCoollecllectiotionn aanndd mmodeodellillinnggffoor ar adadaptaptationtion Nusipepa Lepale Samoa Presentation OutlinePresentation Outline Background info Geography Climate of Samoa Impacts of Climate Change (CC) in Samoa CC Adaptation in Samoa Data Observation Network (Data collection) Modeling used in Samoa Responses to Climate Change in Samoa Samoa Climate Early Warning System (CLEWS) Background InformationBackground Information Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa (formerly known as Western Samoa and German Samoa), is a country governing the western part of the Samoan Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. It became independent from New Zealand in 1962. The two main islands of Samoa are Upolu and one of the biggest islands in Polynesia Savai'i. The capital city Apia and Faleolo International Airport are situated on the island of Upolu. The 1960 Constitution, which formally came into force with independence from New Zealand in 1962, is based on the British pattern of parliamentary democracy, modified to take account of Samoan customs The unicameral legislature (Fono) consists of 49 members serving 5-year terms. Forty-seven are elected from territorial districts by ethnic Samoans; the other two are chosen by non-Samoans with no chiefly affiliation on separate electoral rolls GeographyGeography The country is located east of the international date line and south of the equator, about halfway between Hawai‘i and New Zealand in the Polynesian region of the Pacific Ocean. The total land area is 2934 km² -

Samoa— Polynesian Diving in Upolu Text and Photos by Brandi Mueller

Samoa— Polynesian Diving in Upolu Text and photos by Brandi Mueller 22 X-RAY MAG : 98 : 2020 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO travel Samoa Looking out from the shore past To-Sua Ocean Trench on Upolu Island in Samoa. PREVIOUS PAGE: Seafan and soft coral in Samoa Located in the Polynesian region The small, nine-passenger, turboprop Apia of the South Pacific Ocean, the airplane violently shook us up and down Our destination was Apia, Samoa, and like an amusement park ride. Out of the I was three days late coming in from idyllic paradise of Samoa, which windows, all I could see were the gray Pago Pago, American Samoa because comprises the two main islands clouds of the seemingly endless succes- the airport had been closed due to a of Savai'i and Upolu and sev- sion of storms that had been ravaging line of tropical storms and cyclones that eral smaller islands, is part of the area. just did not seem to stop. Several days Those of us in the back of the small earlier, my original flight from Honolulu the Commonwealth of Nations. plane could see into the cockpit and to Pago Pago had also been delayed Brandi Mueller managed to past the single pilot’s vision and his view for 24 hours due to unsafe weather venture to Upolu Island before was just as impenetrable with thick, dark conditions, and when it was time to the coronavirus pandemic clouds as what we saw through our win- make this short hop, the storms just kept dows. -

April 07 1. Executive Summary. Representatives from the SWPHC

SWPHC8-6 Report on CBC Technical Visit Samoa : April 07 1. Executive Summary. Representatives from the SWPHC and the IHB were pleased to attend the 11th PacMA and 1st Meeting of Ministers for Maritime Transport in Samoa. These meetings deliberated on the application of a range of IMO based policies, programmes, standards and procedures for the Pacific. The hydrographic presentation was well received and a paper was submitted to PacMA with the recommendation adopted by the Ministers of Transport. A number of opportunities were found to improve capacity building in the Pacific. Improving communication on hydrography is relatively straight forward and easily achieved. Linking local hydrographers with other maritime administrators and the sharing of in-country resources such as vessels has considerable merit. Further technical visits to specific countries with operational National Maritime Coordination Committees are recommended. Longer term value is likely to be gained from assessing the most critical capacity building needs and matching them against internal resources, training opportunities, the availability of local vessels and equipment and the services major Hydrographic Authorities are able to supply. Training opportunities described in IHO S-47 are not well known at this prevents countries from seeking access to teaching institutes through either scholarships or aid funding. 2. Background The 2nd meeting of the Capacity Building Committee, held in Fiji in November 2004, determined that support, in the form of a technical visit, was to be provided to the small Island States in the SWPHC. The original intent was to schedule a separate visit for each country however this proved to be logistically difficult. -

Coastal Management Profiles : a Directory of Pacific Island Governments and Non-Government Agencies with Coastal Management Related Responsibilities

A Directory of COASTAL Pacific Island MANAGEMENT Governments and non Government PROFILES Agencies with Coastal Management related Responsibilities henfeld ac W vid Da Photo: SPREP South Pacific Regional Environment Programme SPREP Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Coastal Management Profiles : A Directory of Pacific Island Governments and non-Government Agencies with Coastal Management Related Responsibilities. – Apia, Samoa : SPREP, 1999. vi, 205 p. ; 29 cm ISBN: 982-04-0198-4 1. Coastal zone management – Oceania – Directories. 2. Coastal engineering - Oceania – Directories. I. South Pacific Regional Environment Programme. 025.1641 Published in June 1999 by the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme PO Box 240 Apia, Samoa Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.sprep.org.ws/ Produced by SPREP Edited by Carole Hunter Layout and design by Andreas Wagner (WWd, Australia) email: [email protected] Cover photo: David Wachenfeld (Triggerfish Images, Australia) email: [email protected] Typeset in 9.5/12 (New Century Schoolbook) Printed on recycled paper 90gsm Savannah Matt Art (60%) by Quality Print Ltd, Fiji © South Pacific Regional Environment Programme, 1999. The South Pacific Regional Environment Programme authorises the reproduction of this material, whole or in part, in any form provided appropriate acknowledgement is given. Original Text: English SPREP’s Climate Change and Integrated Coastal Management Programme COASTAL MANAGEMENT PROFILES A DIRECTORY OF PACIFIC ISLAND GOVERNMENTS AND NON GOVERNMENT AGENCIES WITH COASTAL MANAGEMENT RELATED RESPONSIBILITIES South Pacific Regional Environment Programme FOREWORD hese Coastal Management Profiles are a direct response to country requests for a directory containing guidance on who is doing what Tin coastal management within the Pacific islands region. -

Draft Recovery Plan for Five Species from American Sāmoa

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Draft Recovery Plan for Five Species From American Sāmoa J. Malotaux R. Stirnemann Pe'ape'a Vai or Pacific Sheath-tailed BatBatBat Ma'oma'o Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata Gymnomyza samoensis Tu'aimeo or Friendly Ground-Dove J. Malotaux Gallicolumba stairi R. RundellRundellR. Rundell Eua zebrina R. Rundell Ostodes strigatus Draft Recovery Plan for Five Species from American Sāmoa Peʻapeʻa Vai or Pacific Sheath-tailed Bat, South Pacific Subspecies (Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata) Maʻomaʻo or Mao (Gymnomyza samoensis) Tuʻaimeo or Friendly Ground-Dove (Gallicolumba [=Alopecoenas] stairi) American Sāmoa Distinct Population Segment Eua zebrina Ostodes strigatus June 2020 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon Approved: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions needed to recover and/or protect listed species. We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), publish recovery plans, sometimes preparing them with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives of the recovery plan are accomplished, and funds made available, subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities with the same funds. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than our own. They represent our official position only after signed by the Director or Regional Director. Draft recovery plans are reviewed by the public and may be subject to additional peer review before the Service adopts them as final. Recovery objectives may be attained and funds expended contingent upon appropriations, priorities, and other budgetary constraints. -

Polynesian Oral Traditions RAWIRI TAONUI1

Polynesian Oral Traditions RAWIRI TAONUI1 CREATION Creation traditions explain the origins of all things, including the universe, heavens and earth, the gods of nature, all things animate and inanimate in the phenomenological world, male and female forms, and life and death. These mythologies reflect deep-seated philosophical, religious, cultural and social beliefs about the nature of reality and the unknown, being and non- being and the relationship between all things; hence they are regarded as the most sacred of all traditions. MAORI SPEECHMAKING New Zealand Maori celebrated Rangi (Skyfather) and Papa (Earthmother) in whakatauki (aphorisms), waiata (songs) and whaikorero(formal speechmaking) as the following example shows: E mihi atu ki Te Matua, ki a Ranginui, ki a Rangiroa, Greetings to the Skyfather, the Great Heavens, Tawhirirangi, Te Hauwhakaora, the Expansive Heavens Te Hau e pangia nga kiri o te tangata. The Heavenly Winds, the Life Giving Winds, E mihi atu ki a Papatuanuku, ki a Papatuarangi the Winds that caress the skin of all people. Te Papa i takatakahia e nga matua tupuna, Greetings to the Earthmother, Te Papa i waihotia e ratou ma extending beyond the visible land, Te Papa e maroro ki te itinga, e maroro ki te opunga extending beyond the visible heavens Te Papaawhi, e awhi ana i a tatou, o tena, o tena, The Earthmother trampled by our ancestors, o tena o nga whakatupuranga e tupu ake nei the Earthmother left in heritage by them Te Ukaipo, Te Ukaiao mo tatou katoa. The Earthmother that stretches unto the sunrise, that stretches unto the sunset The Embracing Earthmother that embraces each of us from all generations She that sustains us in the night, that sustains us in the day.2 Skyfather And Earthmother The ancestors of the Polynesians transported and relocated their oral traditions as they migrated across the Pacific Ocean. -

BASIC DESIGN STUDY REPORT on the PROJECT for CONSTRUCTION of INTER-ISLAND FERRY in the INDEPENDENT STATE of SAMOA May 2008

MINISTRY OF WORKS, TRANSPORT AND INFRASTRUCTURE No. THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF SAMOA BASIC DESIGN STUDY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION OF INTER-ISLAND FERRY IN THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF SAMOA May 2008 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY FISHERIES ENGINEERING CO., LTD. GL JR 08-066 MINISTRY OF WORKS, TRANSPORT AND INFRASTRUCTURE THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF SAMOA BASIC DESIGN STUDY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION OF INTER-ISLAND FERRY IN THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF SAMOA May 2008 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY FISHERIES ENGINEERING CO., LTD. PREFACE In response to a request from the Government of the Independent State of Samoa, the Government of Japan decided to conduct a basic design study on the Project for Construction of Inter-Island Ferry and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA sent to Samoa a study team from November 13 to December 1, 2007. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Samoa, and conducted a field study at the study area. After the team returned to Japan, further studies were made. Then, a mission was sent to Samoa in order to discuss a draft basic design, and as this result, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Independent State of Samoa for their close cooperation extended to the teams. May 2008 Masafumi Kuroki Vice-President Japan International Cooperation Agency May 2008 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL We are pleased to submit to you the basic design study report on the Project for Construction of Inter-Island Ferry in the independent State of Sama.