Building the New Private Rented Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

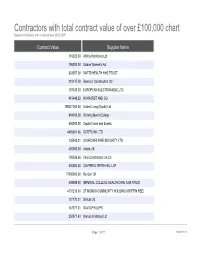

Contractors with Total Contract Value of Over £100,000 Chart Based on Contracts with a Value of Over 5000 GBP

Contractors with total contract value of over £100,000 chart Based on Contracts with a value of over 5000 GBP Contract Value Supplier Name 116325.00 Affinity Workforce Ltd 796000.00 Solace Women's Aid 323557.00 BARTS HEALTH NHS TRUST 210147.00 Boxmoor Construction Ltd 107420.30 EUROPEAN ELECTRONIQUE LTD 415448.22 HAYHURST AND CO 198221000.00 United Living (South) Ltd 894000.00 Working Men's College 450000.00 Capita Travel and Events 4405561.66 CATERLINK LTD 135545.21 CHURCHES FIRE SECURITY LTD 400000.00 Artelia UK 105036.66 Vinci Construction Uk Ltd 500000.00 CAMPBELL REITH HILL LLP 17000000.00 Re-Gen UK 408098.00 IMPERIAL COLLEGE HEALTHCARE NHS TRUST 4707213.00 ST MUNGO COMMUNITY HOUSING (GRIFFIN HSE) 131176.21 Softcat Ltd 147371.31 DAVID PHILLIPS 250971.43 Marcus & Marcus Ltd Page 1 of 22 10/02/2021 Contractors with total contract value of over £100,000 chart Based on Contracts with a value of over 5000 GBP 136044.00 CENTRAL & CECIL 198667.55 GODWIN & CROWNDALE TMC LTD 288142.90 PRICEWATERHOUSECOOPERS 494918.96 APEX HOUSING SOLUTIONS 425000.00 Rick Mather Architects LLP 148855.40 Alderwood LLA Ltd - Irchester 2 821312.26 Falcon Structural Repairs 1169203.00 Ark Build PLC 103675.37 MANOR HOSTELS (LONDON) LTD 319608347.72 VEOLIA ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES (UK) PLC 299532.76 CASTLEHAVEN COMMUNITY ASSOC. 207757.50 PERSONALISATION SUPPORT IN CAMDEN 12000000.00 AD Construction Group 678874.77 St Johns Wood - Lifestyle Care (2011) PLC 424893.63 INSIGHT DIRECT (UK) LTD 150366.19 HOLLY LODGE ESTATE COMMITTEE 114136.63 SPECIALIST COMPUTER CENTRES 943735.13 Mihomecare 4800000.00 Turner & Townsend Project Management Ltd 140000000.00 Volkerhighways 233048.00 KPMG 1150000.00 LONDON DIOCESAN BOARD FOR SCHOOLS Page 2 of 22 10/02/2021 Contractors with total contract value of over £100,000 chart Based on Contracts with a value of over 5000 GBP 302480.00 DAISY DATA CENTRE SOLUTIONS LTD 30000000.00 Eurovia Infrastructure 140126.15 DAWSONRENTALS BUS & COACH LTD 261847.08 ST MARTIN OF TOURS HOUSING ASSOC. -

South East Maidstone Urban Extension Review of Cashflow Model and Viability

South East Maidstone Urban Extension Review of cashflow model and viability Prepared on behalf of Golding Homes 20 April 2012 Final DTZ 125 Old Broad Street London EC2N 2BQ PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL www.dtz.com Review of cashflow model and viability | Golding Homes Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Basis of Instruction 4 2 Golding Homes Financial Model Structure 5 2.1 Key Scheme Details 5 2.2 The Financial Model 6 3 Review of Revenue Assumptions 8 3.1 Revenue 8 3.1.1 Market Sale Housing 8 3.1.2 Affordable Housing 9 3.2 Future House Prices, Absorption and Sales Rates 10 3.2.1 Assumptions about Sales/ Build Out Rates 11 3.3 New Homes Bonus 12 3.4 Current Housing Land Supply 12 4 Review of Cost Assumptions 14 4.1 Cost 14 4.1.1 Unit Sizes 14 4.1.2 Build Costs 14 4.1.3 Code for Sustainable Homes 15 4.1.4 Cost Inflation 15 4.2 On Costs 16 4.3 Planning Contributions (CIL & s106) 17 4.4 Finance Rate 18 4.5 Infrastructure Costs 19 4.6 Land Value 20 4.7 Profit 20 5 Scenario Analysis 22 6 Summary 24 6.1 Delivery Structure 24 6.2 Financial Returns 24 Final 2 Review of cashflow model and viability | Golding Homes Status of Report and Limitations This report contains information which may be commercially sensitive if released. Circulation should be limited to appropriate individuals within Golding Homes. The contents of this report are confidential to Golding Homes in the context in which the report is supplied and DTZ expressly disclaims any responsibility towards third parties in respect of the whole or any part of its contents. -

EMPIRIC STUDENT PROPERTY PLC September 2016 AGENDA and PRESENTATION TEAM

EMPIRIC STUDENT PROPERTY PLC September 2016 AGENDA AND PRESENTATION TEAM Section Page Tim Attlee, MRICS – Founder and CIO Focus on student residential sector since 2009 The UK Student Jointly responsible for the acquisition, development 3 and investment management activities Accommodation Market Held senior roles at Knight Frank Qualified chartered surveyor Company Overview and 6 Highlights THE UK STUDENT ACCOMMODATION MARKET THE UK STUDENT ACCOMMODATION MARKET There are four key trends driving the growth in the purpose built student accommodation (“PBSA”) market The UK population is increasing, putting pressure on housing UK Population Projections (m) 75 70 65 60 55 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020 2024 2028 2032 2036 2040 Source: ONS Local authorities are cutting back on HMOs Given the pressure on housing throughout the UK, local authorities have been attempting to move students out of the traditional “House in multiple occupation” (“HMO”) into PBSAs to provide more housing space for families and workers Source: Arcadis/EC Harris THE UK STUDENT ACCOMMODATION MARKET (CONT’D) Student numbers in the UK are growing at a strong rates Growth in student acceptances for Sept 2015 over Sept 2014 11.0% 3.9% 3.6% 1.9% All Students UK Students EU Students International Students Source: ONS (Non-EU) University owned housing stock is of poor quality "As New" Refurbishment Current university owned PBSA stock is of poor 57,122 quality. Of the 324,532 student beds owned by needed 267,410 universities, only 57,122 are “as new” with the remainder in need of refurbishment or replacement THE UK STUDENT ACCOMMODATION MARKET Demand for UK Higher Education to UK Higher Education keep rising Applicants vs. -

Marketplace Sponsorship Opportunities Information Pack 2017

MarketPlace Sponsorship Opportunities Information Pack 2017 www.airmic.com/marketplace £ Sponsorship 950 plus VAT Annual Conference Website * 1 complimentary delegate pass for Monday www.airmic.com/marketplace only (worth £695)* A designated web page on the MarketPlace Advanced notification of the exhibition floor plan section of the website which will include your logo, contact details and opportunity to upload 20% discount off delegate places any PDF service information documents Advanced notification to book on-site meeting rooms Airmic Dinner Logo on conference banner Advanced notification to buy tickets for the Annual Dinner, 12th December 2017 Logo in conference brochure Access to pre-dinner hospitality tables Opportunity to receive venue branding opportunities Additional Opportunities * This discount is only valid for someone who have never attended an Airmic Conference Airmic can post updates/events for you on before Linked in/Twitter ERM Forum Opportunity to submit articles on technical subjects in Airmic News (subject to editor’s discretion) Opportunity to purchase a table stand at the ERM Forum Opportunity to promote MP content online via @ Airmic Twitter or the Airmic Linked In Group About Airmic Membership Airmic has a membership of about 1200 from about 480 companies. It represents the Insurance buyers for about 70% of the FTSE 100, as well as a very substantial representation in the mid-250 and other smaller companies. Membership continues to grow, and retention remains at 90%. Airmic members’ controls about £5 billion of annual insurance premium spend. A further £2 billion of premium spend is allocated to captive insurance companies within member organisations. Additionally, members are responsible for the payment of insurance claims from their business finances to the value of at least £2 billion per year. -

A Comparative Study of Construction Cost and Commercial Management Services in the UK and China

PERERA, S., ZHOU, L., UDEAJA, C., VICTORIA, M. and CHEN, Q. 2016. A comparative study of construction cost and commercial management services in the UK and China. London: RICS. A comparative study of construction cost and commercial management services in the UK and China. PERERA, S., ZHOU, L., UDEAJA, C., VICTORIA, M. and CHEN, Q. 2016 © 2016 Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. This document was downloaded from https://openair.rgu.ac.uk Research May 2016 A Comparative Study of Construction Cost and Commercial Management Services in the UK and China 中英工程造价管理产业比较研究 GLOBAL/APRIL 2016/DML/20603/RESEARCH GLOBAL/APRIL rics.org/research A Comparative Study of Construction Cost and Commercial Management Services in the UK and China 中英工程造价管理产业比较研究 rics.org/research Report for Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors Report written by: Prof. Srinath Perera PhD MSc IT BSc (Hons) QS MRICS AAIQS Chair in Construction Economics [email protected] kimtag.com/srinath Dr. Lei Zhou Senior Lecturer Dr. Chika Udeaja Senior Lecturer Michele Victoria Researcher Northumbria University northumbria-qs.org Prof. Qijun Chen Director of Human Resource Department, Shandong Jianzhu University RICS Research team Dr. Clare Eriksson FRICS Director of Global Research & Policy [email protected] Amanprit Johal Funded by: Global Research and Policy Manager [email protected] Published by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) RICS, Parliament Square, London SW1P 3AD www.rics.org The views expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of RICS nor any body connected with RICS. Neither the authors, nor RICS accept any liability arising from the use of this publication. -

Global Construction Disputes: a Longer Resolution

Global Construction Disputes Report 2013 Global Construction Disputes: A Longer Resolution echarris.com/contractsolutions Introduction Executive summary This is our third annual report into the construction The key finding of this year’s report into global disputes market. I hope that you will find it to be a construction disputes is that disputes are taking helpful commentary into the regional trends and longer to resolve. insights into a global industry that is often difficult to quantify. Overall, they are now taking over a year to resolve, with the average length of time for a dispute to last in 2012 Overall, this year’s report finds that disputes are taking being 12.8 months, compared to 10.6 months in 2011. longer to resolve and the causes are linked to many different This continues the trends for longer disputes - in 2010 factors, including: disputes were taking 9.1 months to resolve. ■ Disputes that are not settled through negotiation tend Whilst dispute durations are getting longer, the value of to indicate a polarisation of interests, and are likely to disputes was broadly stable in 2012. The average value only contain the most complex of issues; of global construction disputes in 2012 was US$31.7 million, down slightly from US$32.2 million in 2011. ■ Multi-geography, mixed cultures and the need to consult and engage with head offices can prolong the time it takes Longer disputes times – a global trend for a dispute to be concluded; The average length of disputes rose across Asia, the ■ Projects are increasing in complexity and so the issues Middle East and the UK. -

Geographical Distribution and Selection of European Honey Bees Resistant to Varroa Destructor

insects Review Geographical Distribution and Selection of European Honey Bees Resistant to Varroa destructor Yves Le Conte 1,* , Marina D. Meixner 2, Annely Brandt 2, Norman L. Carreck 3,4 , Cecilia Costa 5, Fanny Mondet 1 and Ralph Büchler 2 1 INRAE, Abeilles et Environnement, 84914 Avignon, France; [email protected] 2 Landesbetrieb Landwirtschaft Hessen, Bee Institute, Erlenstrasse 9, 35274 Kirchhain, Germany; [email protected] (M.D.M.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (R.B.) 3 Carreck Consultancy Ltd., Woodside Cottage, Dragons Lane, Shipley RH13 8GD, West Sussex, UK; [email protected] 4 Laboratory of Apiculture and Social Insects, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton BN1 9QG, East Sussex, UK 5 CREA Research Centre for Agriculture and Environment, via di Saliceto 80, 40128 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 3 December 2020; Published: 8 December 2020 Simple Summary: The parasitic mite Varroa destructor is a major challenge to honey bee populations worldwide. Some honey bee populations are resistant to the mite, but most of the commercially used stocks are not and rely on chemical treatment. In this article, we describe known varroa-resistant populations and the mechanisms which have been identified as responsible for survival of colonies without beekeeper intervention to control the mite. We review traits that have potential in breeding programs, discuss the role played by V. destructor as a vector for virus infections, and the changes in mite and virus virulence which could play a role in colony resistance. -

Glenigan Breakfast Briefing: 20 November 2014 Delegate List

Glenigan Breakfast Briefing: 20 November 2014 Delegate List First Name Last Name Title Company Nigel Thomas National Specification & Projects Manager ABB Ltd Carl Turbitt HVAC Sales Manager ABB Ltd Steve Bailey Senior CDM Co-ordinator Academy Consulting Solutions James Williams Associate Academy Consulting Solutions Wayne Allison Project Director Aecom Plc Bradley Edwards Sales Engineer Aggreko UK Ltd Michael Treacy CEO AIC Steel (Rowecord Engineering) Margaret O'Donoghue Manager Corporate Business Allied Irish Bank (GB) Annabelle Wilson Marketing Manager Ancon Ltd Holly Gardiner Land Consultant Arun Estate Agencies Ltd Stephen Naish Land Manager Arun Estate Agencies Ltd Robert Turner Regional Land Manager Arun Estate Agencies Ltd Jason Willetts Director Arun Estate Agencies Ltd Jacqueline Lynch Inside Sales Representative Asite Solutions Ltd Dan Tubby Business Development Director ASM Engineering Ltd Laura Clutton Marketing Executive Astins Ltd John Collins Commercial Director B & M McHugh Ltd Michelle Hall-Hussain Insight & Analytics Manager B B C - TV Licensing Bill Merry Business Development Director Balfour Beatty Engineering Services Ltd Phil Aust National Commercial Manager Ballast Phoenix Ltd Martin Blower Managing Director Bauer Technologies Ltd Rob Hales Land Manager Bellway Homes Ltd John Casey Bennett Construction Ltd Neil Callanan Real Estate Reporter Bloomberg Diego Bonamin Managing Director Bonamin Diego Simon Jones Business Development Manager Bourne Construction Engineering Ltd Oliver Harman Bid Coordinator Bouygues (UK) -

Sustainable Solutions | Digital Leadership | Focus And

Annual Integrated Report 2020 Maximizing Sustainable solutions | Digital Leadership | Focus and Scale Executive Supervisory Financial Other Introduction Board report Board report statements information Arcadis Annual Integrated Report 2020 Maximizing impact “ Climate change, inequality, a growing global population and resulting demand on natural resources put increasingly more strain on societies. We are making the right choices in addressing these challenges by delivering sustainable people-centric solutions, focus where we can win and to maintain a resilient business. We are maximizing our impact in our projects, driven by our passion to improve quality of life, making the world we live in a better place for our people, clients and communities.” Peter Oosterveer, CEO Company fi nancial statements Executive Supervisory Financial Other Introduction Board report Board report statements information Arcadis Annual Integrated Report 2020 New York City Economic Development Corporation and Mayor’s Offi ce of Resiliency | New York, United States Sustainable Protecting Lower Manhattan solutions Strengthening climate Soaring skyscrapers flank historic cobblestone streets. Wall Street borders quaint storefronts. resilience Bustling days are balanced with easy going weekends along the water. As next-door neighbors, Challenge the Financial and Seaport Districts make a dynamic duo. But the distinct and vibrant character Our resilience specialists are of these two neighborhoods also make them particularly susceptible to flooding. The density helping city leaders create a of buildings, low-lying streets, an active waterfront and complex transportation infrastructure comprehensive action plan to present unique challenges. Realizing traditional flood protection measures would not be 62,000 residents protected protect the Financial District feasible, New York City leaders turned to Arcadis to design a bold, new climate resilience plan. -

Investors Drive Sustainability Ed Hammond Notes Uncertainty About When, Or Even Whether, Green Technologies Will Pay Back the Money Invested in Them

GLOBAL PROPERTY INSIGHT FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Tuesday April 17 2012 www.ft.com/property-april2012 | twitter.com/ftreports Investors drive sustainability Ed Hammond notes uncertainty about when, or even whether, green technologies will pay back the money invested in them hen the roof fell in on the international property industry in 2008, it would have Wbeen easy to suppose that envi- ronmental concerns would be put on the back burner. In reality, the relationship between the built environment and sustainability has flourished during the past four years. From landlords attempting to make their buildings as energy efficient as possible, to developers sourcing the most sustainable construction materials and fund managers retrofitting billions of dollars worth of buildings to attract an increasingly environ- mentally conscious investor base, sustainability is now an impor- tant concept in the property industry. And all this in spite of a down- turn that has crippled confidence and activity levels on both sides of the Atlantic. Legislators in Europe, the US developers or owners, is weighing whether this will happen at all. for many organisations, as they Analysts say that before the and Asia are already putting pres- up the benefits of fitting out Moreover, companies facing struggle to cut costs, maintain financial crisis, sustainability sure on owners to improve the buildings to be as environmen- spending cuts may see “green” operations and secure funding for often consisted only of token ges- environmental standards of their tally efficient as possible, against investment as a luxury and focus investment,” says Paul Brown, tures by property companies. buildings and this is expected to the capital needed to do it. -

Detailed Remediation Method Statement

Detailed Remediation Method Statement Land at Five Oaks Lane Chigwell Essex Countryside Properties PLC 514 R02: Issue 1 July 2015 Green Earth Management Co Ltd Title Detailed Remediation Method Statement Land at Five Oaks Lane, Chigwell, Essex Prepared for Countryside Properties Plc Countryside house The Drive Brentwood Essex CM13 3AT Confidentiality, Commercially Confidential copyright and reproduction This document has been prepared by Green Earth Management Company Limited in connection with a contract to supply goods and/or services and is submitted only on the basis of strict confidentiality. The contents must not be disclosed to third parties other than in accordance with the terms of the contract. File reference 514 Report number 514 R02: Issue 1 Date 8th July 2015 Prepared by Green Earth Management Co Ltd East Gores Farm East Gores Road Coggeshall Essex CO6 1RZ Name Signature Date D. Robson 08/07/2015 Author: Reviewed by: P. Taylor 08/07/2015 Authorised by: L. Jackson 08/07/2015 Issue Record Project No 514 Project Name Five Oaks Lane, Chigwell, Essex Client Jackson Civil Engineering on behalf of Countryside Properties Plc Report Title Detailed Remediation Method Statement Report Date of Issue Author Reviewer Details of Changes Distribution No. Issue No. Countryside Properties Plc Jackson Civil Engineering R02 DR PT 08/07/15 Issue 1 Issue 1 EC Harris Arcadis London Borough of Redbridge CONTENTS CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................I -

International Property Handbook: 2017 Trends and a Look Back at 2016 April 2017 Introduction

International Property Handbook: 2017 trends and a look back at 2016 April 2017 Introduction Dear Colleague, The International Property Handbook from Deloitte’s Global Real Estate & Construction group tracks the flows of real estate capital and provides an overview of investment trends and key deals in the most active global real estate investment markets. This handbook reflects back on 2016 analyzing economic data and real estate investment in 21 countries around the world to provide insights on potential trends in 2017. With a strong economic outlook, we saw increases in cross-border investment, yet the overall global transaction volume was around the same as it was in 2015. Private and unlisted funds were the most active investors followed by institutional funds, indicating the large amount of private capital available to be deployed to real estate investment. Given many of the investors still have significant amounts of capital to deploy, and the fundraising market for real estate investment remains strong, we believe that these trends indicate strong growth in the industry moving forward. Large institutional investors and sovereign wealth funds have been initiating or increasing capital allocations to global real estate investments, and we believe that will help sustain real estate investment activity into 2017 and beyond. Our analysis also indicates that while many of the largest real estate investment markets have fully (or nearly fully) recovered from the global financial crisis, other markets are in earlier stages of recovery, indicating potential opportunities for 2017 and beyond. We hope you find this report interesting. We would be delighted to discuss the details of this research with you and how it may impact your business.