G. Resink from the Old Mahabharata - to the New Ramayana-Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kakawin Ramayana

KAKAWIN RAMAYANA Oleh I Ketut Nuarca PROGRAM STUDI SASTRA JAWA KUNO FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS UDAYANA APRIL 2017 Pengantar Peninggalan naskah-naskah lontar (manuscript) baik yang berbahasa Jawa Kuna maupun Bali yang ada di masyarakat Bali telah lama menjadi perhatian para peneliti baik peneliti nusantara maupun asing. Mereka utamanya peneliti asing bukan secara kebetulan tertarik pada naskah-naskah ini tetapi mereka sudah lama menjadikan naskah-naskah tersebut sebagai fokus garapan di beberapa pusat studi kawasan Asia Tenggara utamanya di eropa. Publikasi-publikasi yang ada selama ini telah membuktikan tingginya kepedulian mereka pada bidang yang satu ini. Hal ini berbeda keadaannya dibandingkan dengan di Indonesia. Luasnya garapan tentang bidang ini menuntut adanya komitmen pentingnya digagas upaya-upaya antisipasi untuk menghindari punahnya naskah-naskah dimaksud. Hal ini penting mengingat masyarakat khususnya di Bali sampai sekarang masih mempercayai bahwa naskah- naskah tersebut adalah sebagai bagian dari khasanah budaya bangsa yang di dalamnya mengandung nilai-nilai budaya yang adi luhung. Di Bali keberadaan naskah-naskah klasik ini sudah dianggap sebagai miliknya sendiri yang pelajari, ditekuni serta dihayati isinya baik secara perorangan maupun secara berkelompok seperti sering dilakukan melalui suatu tradisi sastra yang sangat luhur yang selama ini dikenal sebagai tradisi mabebasan. Dalam tradisi ini teks-teks klasik yang tergolong sastra Jawa Kuna dan Bali dibaca, ditafsirkan serta diberikan ulasan isinya sehingga terjadi diskusi budaya yang cukup menarik banyak kalangan. Tradisi seperti ini dapat dianggap sebagai salah satu upaya bagaimana masyarakat Bali melestarikan warisan kebudayaan nenek moyangnya, serta sedapat mungkin berusaha menghayati nilai-nilai yang terkandung di dalam naskah-naskah tersebut. Dalam tradisi ini teks-teks sastra Jawa Kuna menempati posisi paling unggul yang paling banyak dijadikan bahan diskusi. -

Gagal Paham Memaknai Kakawin Sebagai Pengiring Upacara Yadnya Dan Dalam Menembangkannya: Sebuah Kasus Di Desa Susut, Bangli

GAGAL PAHAM MEMAKNAI KAKAWIN SEBAGAI PENGIRING UPACARA YADNYA DAN DALAM MENEMBANGKANNYA: SEBUAH KASUS DI DESA SUSUT, BANGLI. I Ketut Jirnaya, Komang Paramartha, I Made wijana, I Ketut Nuarca Program tudi Sastra Jawa Kuno, akultas Ilmu Budaya, Universitas Udayana E-mail: [email protected] Abstrak Karya sastra kakawin di Bali sering dipakai untuk mengiringi upacara yadnya. Dari itu banyak terbit dan beredar di masyarakat buku saku Kidung Pancayadnya. Isi setiap buku tersebut nyaris sama. Buku-buku ini membangun pemahaman masyarakat bahwa kakawin yang dipakai untuk mengiringi upacara yadnya telah baku tanpa melihat substansi makna filosofi bait-bait tersebut. Masalahnya beberapa anggota masyarakat berpendapat ada bait-bait kakawin yang biasa dipakai mengiringi upacara kematian, tidak boleh dinyanyikan di pura. Di samping itu juga cara menembangkan kakawin belum baik dan benar. Hal ini juga terjadi di desa Susut, Bangli. Setelah dikaji, ternyata mereka salah memahami makna filosofis bait-bait kakawin tersebut. Hasilnya, semua bait kakawin bisa dinyanyikan di pura karena salah satu fungsinya sebagai sarana berdoa. Setiap upacara yadnya diiringi dengan melantunkan bait-bait kakawin yang telah disesuaikan substansi makna dari bait-bait tersebut dengan yadnya yang diiringi. Demikian pula mereka baru tahu bahwa menembangkan kakawin ada aturannya. Kata kunci: kakawin, yadnya, doa, guru-lagu. 1.Pendahuluan Kakawin dan parwa merupakan karya sastra Jawa Kuna yang hidup subur pada zaman Majapahit. Ketika Majapahit jatuh dan masuknya agama Islam, maka karya sastra kakawin banyak yang diselamatkan di Bali yang masih satu kepercayaan dengan Majapahit yaitu Hindu (Zoetmulder, 1983). Dari segi bentuk, kakawin berbentuk puisi dengan persyaratan (prosodi) satu bait terdiri dari empat baris yang diikat dengan guru-lagu. -

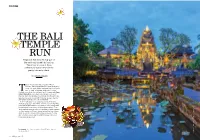

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Of Manuscripts and Charters Which Are Mentioned In

INDEX OF MANUSCRIPTS AND CHARTERS WHICH ARE MENTIONED IN TABLES A AND B 1 Page Page Adip. - Adiparwa . 94 Dj.pur. - Jayapural}.a . 106 Ag. - Agastyaparwa . 103 Dpt. - VangQang petak . 106 A.N. - Afiang Nilartha . 1(}3 A.P. - Arjuna Pralabda 103 E46 91 A.W. - Arjunawijaya 100 Gh. - Ghatotkaca.\;raya 97 Babi Ch. A . 94 G.O. - GeQangan Ch. 90 BarabuQur (inscription) 90 Gob1eg Ch. (Pura Batur) B . 95 Batuan Ch.. 94 Batunya Ch. A I . 93 H. - Hari\;raya Kakawin 106 Batur P. Abang Ch. A 94 Hr. - Hariwijaya 106 B.B. - Babad Bla-Batuh 103 Hrsw. - Kidung Har~awijaya . 107 Bebetin Ch. A I . 91 H.W. - Hariwang\;a 95 B.K. - Bhoma.lcawya . 104 J.D. - Mausalaparwa . 110 B.P. - Bhi~maparwa . 104 Br. I pp. 607 ff. 95 K.A. - Kembang Arum Ch. 92 pp. 613 ff.. 95 Kid. Adip. - Kidung Adiparwa 106 pp. 619 ff.. 95 K.K. - KufijarakarQ.a . 108 Br. II pp. 49 if. 95 K.O. I . 92 Brh. - Brahmal}.Qa-pural}.a . 105 II 90 Bs. - Bhimaswarga 104 V 94 B.T. - Bagus Turunan 104 VII . 93 Bulihan Ch.. 97 VIII 92 Buwahan Ch. A 93 XI 91 Buwahan Ch. E 97 XIV 91 B.Y. - Bharatayuddha 96 XV. 91 XVII 92 C. - Cupak 106 XXII 93 c.A. - Calon Arang 105 Kor. - Korawa\;rama . 108 Campaga Ch. A 97 Kr. - Krtabasa 108 Campaga Ch. C 99 Kr.B. - Chronicle of Bayu . 106 Catur. - Caturyuga 106 Krsn. - Kr~l}.iintaka 108 Charter Frankfurt N.S. K.S. - Kidung Sunda . 101 No. -

Dharma As a Consequentialism the Threat of Hridayananda Das Goswami’S Consequentialist Moral Philosophy to ISKCON’S Spiritual Identity

Dharma as a Consequentialism The threat of Hridayananda das Goswami’s consequentialist moral philosophy to ISKCON’s spiritual identity. Krishna-kirti das 3/24/2014 This paper shows that Hridayananda Das Goswami’s recent statements that question the validity of certain narrations in authorized Vedic scriptures, and which have been accepted by Srila Prabhupada and other acharyas, arise from a moral philosophy called consequentialism. In a 2005 paper titled “Vaisnava Moral Theology and Homosexuality,” Maharaja explains his conception consequentialist moral reasoning in detail. His application of it results in a total repudiation of Srila Prabhupada’s authority, a repudiation of several acharyas in ISKCON’s parampara, and an increase in the numbers of devotees whose Krishna consciousness depends on the repudiation of these acharyas’ authority. A non- consequentialist defense of Śrīla Prabhupāda is presented along with recommendations for resolving the existential threat Maharaja’s moral reasoning poses to the spiritual well-being of ISKCON’s members, the integrity of ISKCON itself, and the authenticity of Srila Prabhupada’s spiritual legacy. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Dharma as a Consequentialism ..................................................................................................................... 1 Maharaja’s application of consequentialism to Krishna Consciousness ..................................................... -

Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

S International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India Volume: 7 Abstract Disability has been the inescapable part of human society from ancient times. With the thrust of Issue: 1 disability right movements and development in eld of disability studies, the mythical past of dis- ability is worthy to study. Classic Indian Scriptures mention differently able character in prominent positions. There is a faulty opinion about Indian mythology is that they associate disability chie y Month: July with evil characters. Hunch backed Manthara from Ramayana and limping legged Shakuni from Mahabharata are negatively stereotyped characters. This paper tries to analyze that these charac- ters were guided by their motives of revenge, loyalty and acted more as dramatic devices to bring Year: 2019 crucial changes in plot. The deities of lord Jagannath in Puri is worshipped , without limbs, neck and eye lids which ISSN: 2321-788X strengthens the notion that disability is an occasional but all binding phenomena in human civiliza- tion. The social model of disability brings forward the idea that the only disability is a bad attitude for the disabled as well as the society. In spite of his abilities Dhritrashtra did face discrimination Received: 31.05.2019 because of his blindness. The presence of characters like sage Ashtavakra and Vamanavtar of Lord Vishnu indicate that by efforts, bodily limitations can be transcended. Accepted: 25.06.2019 Keywords: Karma, Medical model, Social model, Ability, Gender, Charity, Rights. -

About Yajna, Yaga & Homa

Mahabharata Series About Yajna, Yaga & Homa Compiled by: G H Visweswara PREFACE I have extracted these contents from my other comprehensive & unique work on Mahabharata called Mahabharata-Spectroscope. (See http://www.ghvisweswara.com/mahabharata-2/mahabharata-spectroscope-a-unique- resource/). Whereas the material in that was included in the order in which it appears in the original epic, in this compilation I have grouped them by meaningful Topics & Sub- topics thus making it much more useful to the student/scholar of this subject. This is a brief compilation of the contents appearing in the great epic Mahabharata on the topics of Yajna, Yaga & Homa. The compilation is not exhaustive in the sense that every para appearing in the great epic is not included here for the sake of limiting the size of this document. Some of the topics like japa-yajna have already been compiled in another document called Japa-Dhayana-Pranayama. But still most of the key or representative passages have been compiled here. The contents are from Mahabharata excluding Bhagavad Gita. I hope the readers will find the document of some use in their study on these topics. Please see http://www.ghvisweswara.com/mahabharata-2 for my other topic based compilations based on Mahabharata. G H Visweswara [email protected] www.ghvisweswara.com March 2017 About Yajna, Yaga & Homa in Mahabharata: G H Visweswara Page 1 Table of Contents About Yajna, Yaga & Homa in Mahabharata .......................................................................................... 4 Eligibility, -

THE DIVISION of CONTINUING EDUCATION and COMMUNITY SERVICE the STATE FOUNDATION on CULTURE and the ARTS and the UNIVERSITY THEATRE Present

THE DIVISION OF CONTINUING EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY SERVICE THE STATE FOUNDATION ON CULTURE AND THE ARTS AND THE UNIVERSITY THEATRE present by special arrangements with the American Society for Eastern Arts San Francisco, California John F. Kennedy Theatre University of Hawaii September 24, 25, 1970 /(ala mania/am /(aiAahali Company The Kerala Kalamandalam (the Kerala State Academy of the Arts) was founded in 1930 by ~lahaka vi Vallathol, poet laureate of Kerala, to ensure the continuance of the best tradi tions in Kathakali. The institution is nO\\ supported by both State and Central Governments and trains most of the present-day Kathakali actors, musicians and make-up artists. The Kerala Kalamandalam Kathakali company i::; the finest in India. Such is the demand for its performances that there is seldom a "night off" during the performing season . Most of the principal actors are asatts (teachers) at the in::;titution. In 1967 the com pany first toured Europe, appearing at most of the summer festi vals, including Jean-Louis Barrault's Theatre des Nations and 15 performances at London's Saville Theatre, as well as at Expo '67 in Montreal. The next year, they we re featured at the Shiraz-Persepolis International Festival of the Arts in I ran. This August the Kerala Kalamandalam company performed at Expo '70 in Osaka and subsequently toured Indonesia, Australia and Fiji. This. their first visit to the Cnited States, is presented by the American Society for Eastern Arts. ACCOMPANISTS FOR BOTH PROGRAMS Singers: Neelakantan Nambissan S. Cangadharan -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

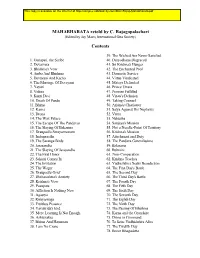

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

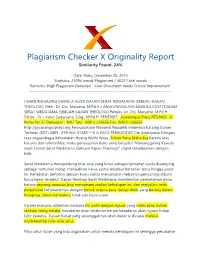

Plagiarism Checker X Originality Report Similarity Found: 24%

Plagiarism Checker X Originality Report Similarity Found: 24% Date: Rabu, Desember 30, 2019 Statistics: 25094 words Plagiarized / 6022 Total words Remarks: High Plagiarism Detected - Your Document needs Critical Improvement. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- i MANUNGGALING KAWULA GUSTI DALAM SERAT WEDATAMA (SEBUAH KAJIAN THEOLOGI) Oleh : Dr. Drs. Marsono, M.Pd.H ii MANUNGGALING KAWULA GUSTI DALAM SERAT WEDATAMA (SEBUAH KAJIAN THEOLOGI) Penulis: Dr. Drs. Marsono, M.Pd.H Editor : Dr. I Ketut Sudarsana, S.Ag., M.Pd.H. PENERBIT : Jayapangus Press REDAKSI : Jl. Ratna No.51 Denpasar - BALI Telp. (0361) 226656 Fax. (0361) 226656 http://jayapanguspress.org Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT) ISBN : 978-602-51483-1-6 iii KATA PENGANTAR Om Swastyastu Dengan rasa angayubagia kehadapan Hyang Widhi Wasa, Tuhan Yang Maha Esa karena atas karunia dan rahmatNya, maka penyusunan buku yang berjudul “Manunggaling Kawula Gusti Dalam Serat Wedatama (Sebuah Kajian Theologi)” dapat terselesaikan dengan baik. Serat Wedatama mengandung nilai-nilai yang luhur sebagai tuntunan susila disamping sebagai tuntunan hidup, menjadikan karya sastra tersebut bertahan terus hingga saaat ini. Kehebatan bertahan sebuah karya sastra menunjukan hebatnya pengarang dibalik karya besar tersebut. Kajian theologi Serat Wedatama memberikan pemahaman dasar bahwa seorang manusia bisa memahami makna kehidupan ini, dan menjalani roda perputaran kehidupannya dengan penuh makna pula. Setiap detik yang berlalu dalam hidupnya, selalu bermakna, tidak ada kesia-siaan. Karena manusia dilahirkan kedunia ini, pasti dengan tujuan yang mulia pula, bukan sekedar iseng belaka. Kesadaran akan kelahiran berarti kesadaran akan tujuan hidup lahir kedunia. Tujuan hidup yang sesungguhnya akan dapat iv dicapai melalui implementasi nilai-nilai luhur. Nilai luhur itulah yang bias digunakan untuk menata kehidupan ini sehingga perubahan menuju penyeimbangan antara pemenuhan spiritual dan jasmani tercapai. -

H. Creese Ultimate Loyalties. the Self-Immolation of Women in Java and Bali

H. Creese Ultimate loyalties. The self-immolation of women in Java and Bali In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Old Javanese texts and culture 157 (2001), no: 1, Leiden, 131-166 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl HELEN CREESE Ultimate Loyalties The Self-immolation of Women in Java and Bali Her deep sorrow became intolerable) and as there seemed nothing else to wait for, she. hurriedly prepared herself for death. She drew the dagger she had been holding all the while, which sparkled now taken from its sheath. She then threw herself fearlessly on it,.and her blood gushed forth like red mineral. (Bharatayuddha.45.1-45.2, Supomo 1993:242.1) With this, Satyawati, the wife of the hero Salya, cruelly slain in the battle between the Pandawas and Korawas, ends her life in the ultimate display of love and fidelity, choosing to follow her husband to the next world rather • than remain in this one without him. On hearing the news of Salya's death, Satyawati sets out to join him, firm in the knowledge that 'her life began to end the moment she fell asleep the night before', when &alya slipped from her bed and left her, and although she 'still had a body [...] it was just like a casket, for her spirit had gone when the king went into battle' {Bharatayuddha 42.4). Accompanied by her maid, Sugandhika, she wanders the battlefield, slip- ping in its 'river of blood' and stumbling over 'stinking corpses' as she search- es in vain for Salyas body.