The Ur-Mahabharata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Peacock Cult in Asia

The Peacock Cult in Asia By P. T h a n k a p p a n N a ir Contents Introduction ( 1 ) Origin of the first Peacock (2) Grand Moghul of the Bird Kingdom (3) How did the Peacock get hundred eye-designs (4) Peacock meat~a table delicacy (5) Peacock in Sculptures & Numismatics (6) Peacock’s place in history (7) Peacock in Sanskrit literature (8) Peacock in Aesthetics & Fine Art (9) Peacock’s place in Indian Folklore (10) Peacock worship in India (11) Peacock worship in Persia & other lands Conclusion Introduction Doubts were entertained about India’s wisdom when Peacock was adopted as her National Bird. There is no difference of opinion among scholars that the original habitat of the peacock is India,or more pre cisely Southern India. We have the authority of the Bible* to show that the peacock was one of the Commodities5 that India exported to the Holy Land in ancient times. This splendid bird had reached Athens by 450 B.C. and had been kept in the island of Samos earlier still. The peacock bridged the cultural gap between the Aryans who were * I Kings 10:22 For the king had at sea a navy of Thar,-shish with the navy of Hiram: once in three years came the navy of Thar’-shish bringing gold, and silver,ivory, and apes,and peacocks. II Chronicles 9: 21 For the King’s ships went to Tarshish with the servants of Hu,-ram: every three years once came the ships of Tarshish bringing gold, and silver,ivory,and apes,and peacocks. -

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Väkivallan Muodot Ja Sen Kuvaamisen Keinot Arundhati Royn Teoksessa the God of Small Things Ja Bernardine Evariston Runoromaanissa the Emperor’S Babe

TAMPEREEN YLIOPISTO Raisa Aho Miten kertoa kivusta? Väkivallan muodot ja sen kuvaamisen keinot Arundhati Royn teoksessa The God of Small Things ja Bernardine Evariston runoromaanissa The Emperor’s Babe Yleisen kirjallisuustieteen pro gradu -tutkielma Tampere 2011 Tampereen yliopisto, Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö AHO, Raisa: Miten kertoa kivusta? Väkivallan muodot ja sen kuvaamisen keinot Arundhati Royn romaanissa The God of Small Things ja Bernardine Evariston runoteoksessa The Emperor’s Babe Pro Gradu -tutkielma, 128 s. Yleinen kirjallisuustiede Huhtikuu 2011 Yleisen kirjallisuustieteen pro gradu -tutkielmassani tarkastelen erilaisia väkivallan ilmenemismuotoja ja niiden kuvaamisen keinoja kahdessa kaunokirjallisessa teoksessa, eli Arundhati Royn romaanissa The God of Small Things (1997) ja Bernardine Evariston runoromaanissa The Emperor’s Babe (2001). Päädyin tarkastelemaan juuri näitä kahta teosta rinnakkain sekä sisällöllisistä, temaattisista, kirjallisuushistoriallisista että kerronnallisista syistä. Ne molemmat kuuluvat niin sanotun postkoloniaalisen kirjallisuuden traditioon, mutta eri tavoilla. Molemmissa käsitellään väkivaltaa ja sen traumatisoivaa luonnetta, mutta kertojaratkaisujen erot tuovat väkivallan kuvauksiin erilaisia painotuksia. Tutkimukseni lähtee liikkeelle sekä ruumiillisen kivun että traumaattisen kokemuksen kieltä pakenevasta luonteesta. Molempia ilmiöitä on tarkasteltu siitä lähtökohdasta, että ne ovat symboloimattomia, ja niiden sanoiksi pukeminen on vaikeaa, ellei peräti mahdotonta. Kivun -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

Introduction to BI-Tagavad-Gita

TEAcI-tER'S GuidE TO INTROduCTioN TO BI-tAGAVAd-GiTA (DAModAR CLASS) INTROduCTioN TO BHAqAVAd-qiTA Compiled by: Tapasvini devi dasi Hare Krishna Sunday School Program is sponsored by: ISKCON Foundation Contents Chapter Page Introduction 1 1. History ofthe Kuru Dynasty 3 2. Birth ofthe Pandavas 10 3. The Pandavas Move to Hastinapura 16 4. Indraprastha 22 5. Life in Exile 29 6. Preparing for Battle 34 7. Quiz 41 Crossword Puzzle Answer Key 45 Worksheets 46 9ntroduction "Introduction to Bhagavad Gita" is a session that deals with the history ofthe Pandavas. It is not meant to be a study ofthe Mahabharat. That could be studied for an entire year or more. This booklet is limited to the important events which led up to the battle ofKurlLkshetra. We speak often in our classes ofKrishna and the Bhagavad Gita and the Battle ofKurukshetra. But for the new student, or student llnfamiliar with the history ofthe Pandavas, these topics don't have much significance ifthey fail to understand the reasons behind the Bhagavad Gita being spoken (on a battlefield, yet!). This session will provide the background needed for children to go on to explore the teachulgs ofBhagavad Gita. You may have a classroonl filled with childrel1 who know these events well. Or you may have a class who has never heard ofthe Pandavas. You will likely have some ofeach. The way you teach your class should be determined from what the children already know. Students familiar with Mahabharat can absorb many more details and adventures. Young children and children new to the subject should learn the basics well. -

PDF Format of This Book

COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD SWAMI KRISHNANANDA Published by THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India www.sivanandaonline.org, www.dlshq.org First Edition: 2017 [1,000 copies] ©The Divine Life Trust Society EK 56 PRICE: ` 95/- Published by Swami Padmanabhananda for The Divine Life Society, Shivanandanagar, and printed by him at the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy Press, P.O. Shivanandanagar, Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India For online orders and catalogue visit: www.dlsbooks.org puBLishers’ note We are delighted to bring our new publication ‘Commentary on the Mundaka Upanishad’ by Worshipful Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj. Saunaka, the great householder, questioned Rishi Angiras. Kasmin Bhagavo vijnaate sarvamidam vijnaatam bhavati iti: O Bhagavan, what is that which being known, all this—the entire phenomena, experienced through the mind and the senses—becomes known or really understood? The Mundaka Upanishad presents an elaborate answer to this important philosophical question, and also to all possible questions implied in the one original essential question. Worshipful Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj gave a verse-by-verse commentary on this most significant and sacred Upanishad in August 1989. The insightful analysis of each verse in Sri Swamiji Maharaj’s inimitable style makes the book a precious treasure for all spiritual seekers. —THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY 5 TABLE OF Contents Publisher’s Note . 5 CHAPTER 1: Section 1 . 11 Section 2 . 28 CHAPTER 2: Section 1 . 50 Section 2 . 68 CHAPTER 3: Section 1 . 85 Section 2 . 101 7 COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD Chapter 1 SECTION 1 Brahmā devānām prathamaḥ sambabhūva viśvasya kartā bhuvanasya goptā, sa brahma-vidyāṁ sarva-vidyā-pratiṣṭhām arthavāya jyeṣṭha-putrāya prāha; artharvaṇe yām pravadeta brahmātharvā tām purovācāṅgire brahma-vidyām, sa bhāradvājāya satyavāhāya prāha bhāradvājo’ṇgirase parāvarām (1.1.1-2). -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

Dr Anupama.Pdf

NJESR/July 2021/ Vol-2/Issue-7 E-ISSN-2582-5836 DOI - 10.53571/NJESR.2021.2.7.81-91 WOMEN AND SAMSKRIT LITERATURE DR. ANUPAMA B ASSISTANT PROFESSOR (VYAKARNA SHASTRA) KARNATAKA SAMSKRIT UNIVERSITY BENGALURU-560018 THE FIVE FEMALE SOULS OF " MAHABHARATA" The Mahabharata which has The epics which talks about tradition, culture, laws more than it talks about the human life and the characteristics of male and female which most relevant to this modern period. In Indian literature tradition the Ramayana and the Mahabharata authors talks not only about male characters they designed each and every Female characters with most Beautiful feminine characters which talk about their importance and dutiful nature and they are all well in decision takers and live their lives according to their decisions. They are the most powerful and strong and also reason for the whole Mahabharata which Occur. The five women in particular who's decision makes the whole Mahabharata to happen are The GANGA, SATYAVATI, AMBA, KUNTI and DRUPADI. GANGA: When king shantanu saw Ganga he totally fell for her and said "You must certainly become my wife, whoever you may be." Thus said the great King Santanu to the goddess Ganga who stood before him in human form, intoxicating his senses with her superhuman loveliness 81 www.njesr.com The king earnestly offered for her love his kingdom, his wealth, his all, his very life. Ganga replied: "O king, I shall become your wife. But on certain conditions that neither you nor anyone else should ever ask me who I am, or whence I come. -

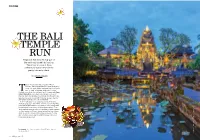

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Bovine Benefactories: an Examination of the Role of Religion in Cow Sanctuaries Across the United States

BOVINE BENEFACTORIES: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN COW SANCTUARIES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES _______________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ________________________________________________________________ by Thomas Hellmuth Berendt August, 2018 Examing Committee Members: Sydney White, Advisory Chair, TU Department of Religion Terry Rey, TU Department of Religion Laura Levitt, TU Department of Religion Tom Waidzunas, External Member, TU Deparment of Sociology ABSTRACT This study examines the growing phenomenon to protect the bovine in the United States and will question to what extent religion plays a role in the formation of bovine sanctuaries. My research has unearthed that there are approximately 454 animal sanctuaries in the United States, of which 146 are dedicated to farm animals. However, of this 166 only 4 are dedicated to pigs, while 17 are specifically dedicated to the bovine. Furthermore, another 50, though not specifically dedicated to cows, do use the cow as the main symbol for their logo. Therefore the bovine is seemingly more represented and protected than any other farm animal in sanctuaries across the United States. The question is why the bovine, and how much has religion played a role in elevating this particular animal above all others. Furthermore, what constitutes a sanctuary? Does -

The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen

The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen To cite this version: Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen. The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and philological papers on a Vedic tradition. Arlo Griffiths; Annette Schmiedchen. 11, Shaker, 2007, Indologica Halensis, 978-3-8322-6255-6. halshs-01929253 HAL Id: halshs-01929253 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01929253 Submitted on 5 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Griffiths, Arlo, and Annette Schmiedchen, eds. 2007. The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and Philological Papers on a Vedic Tradition. Indologica Halensis 11. Aachen: Shaker. Contents Arlo Griffiths Prefatory Remarks . III Philipp Kubisch The Metrical and Prosodical Structures of Books I–VII of the Vulgate Atharvavedasam. hita¯ .....................................................1 Alexander Lubotsky PS 8.15. Offense against a Brahmin . 23 Werner Knobl Zwei Studien zum Wortschatz der Paippalada-Sam¯ . hita¯ ..................35 Yasuhiro Tsuchiyama On the meaning of the word r¯as..tr´a: PS 10.4 . 71 Timothy Lubin The N¯ılarudropanis.ad and the Paippal¯adasam. hit¯a: A Critical Edition with Trans- lation of the Upanis.ad and Nar¯ ayan¯ . a’s D¯ıpik¯a ............................81 Arlo Griffiths The Ancillary Literature of the Paippalada¯ School: A Preliminary Survey with an Edition of the Caran.