Women's Mourning in the Striparvan of the Mahabharata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

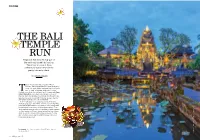

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Dharma As a Consequentialism the Threat of Hridayananda Das Goswami’S Consequentialist Moral Philosophy to ISKCON’S Spiritual Identity

Dharma as a Consequentialism The threat of Hridayananda das Goswami’s consequentialist moral philosophy to ISKCON’s spiritual identity. Krishna-kirti das 3/24/2014 This paper shows that Hridayananda Das Goswami’s recent statements that question the validity of certain narrations in authorized Vedic scriptures, and which have been accepted by Srila Prabhupada and other acharyas, arise from a moral philosophy called consequentialism. In a 2005 paper titled “Vaisnava Moral Theology and Homosexuality,” Maharaja explains his conception consequentialist moral reasoning in detail. His application of it results in a total repudiation of Srila Prabhupada’s authority, a repudiation of several acharyas in ISKCON’s parampara, and an increase in the numbers of devotees whose Krishna consciousness depends on the repudiation of these acharyas’ authority. A non- consequentialist defense of Śrīla Prabhupāda is presented along with recommendations for resolving the existential threat Maharaja’s moral reasoning poses to the spiritual well-being of ISKCON’s members, the integrity of ISKCON itself, and the authenticity of Srila Prabhupada’s spiritual legacy. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Dharma as a Consequentialism ..................................................................................................................... 1 Maharaja’s application of consequentialism to Krishna Consciousness ..................................................... -

Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

S International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India Volume: 7 Abstract Disability has been the inescapable part of human society from ancient times. With the thrust of Issue: 1 disability right movements and development in eld of disability studies, the mythical past of dis- ability is worthy to study. Classic Indian Scriptures mention differently able character in prominent positions. There is a faulty opinion about Indian mythology is that they associate disability chie y Month: July with evil characters. Hunch backed Manthara from Ramayana and limping legged Shakuni from Mahabharata are negatively stereotyped characters. This paper tries to analyze that these charac- ters were guided by their motives of revenge, loyalty and acted more as dramatic devices to bring Year: 2019 crucial changes in plot. The deities of lord Jagannath in Puri is worshipped , without limbs, neck and eye lids which ISSN: 2321-788X strengthens the notion that disability is an occasional but all binding phenomena in human civiliza- tion. The social model of disability brings forward the idea that the only disability is a bad attitude for the disabled as well as the society. In spite of his abilities Dhritrashtra did face discrimination Received: 31.05.2019 because of his blindness. The presence of characters like sage Ashtavakra and Vamanavtar of Lord Vishnu indicate that by efforts, bodily limitations can be transcended. Accepted: 25.06.2019 Keywords: Karma, Medical model, Social model, Ability, Gender, Charity, Rights. -

About Yajna, Yaga & Homa

Mahabharata Series About Yajna, Yaga & Homa Compiled by: G H Visweswara PREFACE I have extracted these contents from my other comprehensive & unique work on Mahabharata called Mahabharata-Spectroscope. (See http://www.ghvisweswara.com/mahabharata-2/mahabharata-spectroscope-a-unique- resource/). Whereas the material in that was included in the order in which it appears in the original epic, in this compilation I have grouped them by meaningful Topics & Sub- topics thus making it much more useful to the student/scholar of this subject. This is a brief compilation of the contents appearing in the great epic Mahabharata on the topics of Yajna, Yaga & Homa. The compilation is not exhaustive in the sense that every para appearing in the great epic is not included here for the sake of limiting the size of this document. Some of the topics like japa-yajna have already been compiled in another document called Japa-Dhayana-Pranayama. But still most of the key or representative passages have been compiled here. The contents are from Mahabharata excluding Bhagavad Gita. I hope the readers will find the document of some use in their study on these topics. Please see http://www.ghvisweswara.com/mahabharata-2 for my other topic based compilations based on Mahabharata. G H Visweswara [email protected] www.ghvisweswara.com March 2017 About Yajna, Yaga & Homa in Mahabharata: G H Visweswara Page 1 Table of Contents About Yajna, Yaga & Homa in Mahabharata .......................................................................................... 4 Eligibility, -

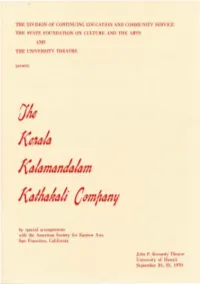

THE DIVISION of CONTINUING EDUCATION and COMMUNITY SERVICE the STATE FOUNDATION on CULTURE and the ARTS and the UNIVERSITY THEATRE Present

THE DIVISION OF CONTINUING EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY SERVICE THE STATE FOUNDATION ON CULTURE AND THE ARTS AND THE UNIVERSITY THEATRE present by special arrangements with the American Society for Eastern Arts San Francisco, California John F. Kennedy Theatre University of Hawaii September 24, 25, 1970 /(ala mania/am /(aiAahali Company The Kerala Kalamandalam (the Kerala State Academy of the Arts) was founded in 1930 by ~lahaka vi Vallathol, poet laureate of Kerala, to ensure the continuance of the best tradi tions in Kathakali. The institution is nO\\ supported by both State and Central Governments and trains most of the present-day Kathakali actors, musicians and make-up artists. The Kerala Kalamandalam Kathakali company i::; the finest in India. Such is the demand for its performances that there is seldom a "night off" during the performing season . Most of the principal actors are asatts (teachers) at the in::;titution. In 1967 the com pany first toured Europe, appearing at most of the summer festi vals, including Jean-Louis Barrault's Theatre des Nations and 15 performances at London's Saville Theatre, as well as at Expo '67 in Montreal. The next year, they we re featured at the Shiraz-Persepolis International Festival of the Arts in I ran. This August the Kerala Kalamandalam company performed at Expo '70 in Osaka and subsequently toured Indonesia, Australia and Fiji. This. their first visit to the Cnited States, is presented by the American Society for Eastern Arts. ACCOMPANISTS FOR BOTH PROGRAMS Singers: Neelakantan Nambissan S. Cangadharan -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

G. Resink from the Old Mahabharata - to the New Ramayana-Order

G. Resink From the old Mahabharata - to the new Ramayana-order In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 131 (1975), no: 2/3, Leiden, 214-235 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 04:10:30AM via free access G. J. RESINK FROM THE OLD MAHABHARATA- TO THE NEW RAMAYANA-ORDER* ". the Bharata Judha can be performed again — when Java will again be free . ." Pronouncement of a nineteenth century dalang. Some people not only live, but also die and kill by myths. So the well-known Darul Islam leader S. M. Kartosoewirjo wrote in a secret note to President Soekarno in 1951, prophesying entirely from the myth of a Javanese version of the Mahabharata epic, that a "Perang Brata Juda Djaja Binangun" was imminent. This conflict would lead to a confrontation with Communism — to which the expression "Lautan Merah" alluded —- and world revolution.1 The Javanese santri who was to advocate and lead the jihad or holy war in defence of an Islamic Indonesian state was writing to the Javanese abangan here in terms which both understood perfectly well. For it was precisely this wayang story that was usually staged as a bersih desa rite or a ngruwat ceremony for purposes of "purification" or the exorcism of all evil and misfortune that had ever struck or threatened still to befall the community. As a student I once witnessed such a performance together with my mother in the village of Karang Asem, to the north of Yogya. She wrote about it in the journal Djdwd, referring in particular to how the women fled the scène towards mid- * I feel most indebted to Dr. -

Maharshi Vyasa, Sage Yajnavalkya, Yogi Bhusanda, Dattatreya, Yogi Jaigisavya, Thirumula Nayanar

LIVES OF INDIAN SAINTS I read a bit about the saints of India in a school. We were not taught in a manner whereby one could get composite knowledge about Indian saints, the sole purpose was to mug up and get through the exams. Ever since I left school, in my subconscious mind, there was a desire to find a book that told me about Indian saints. This desire was fulfilled 23 years later when I found a book “Lives of Saints” by Swami Sivananda. What is happiness or knowledge if not shared? So I am reproducing the book for you. My comments are in brackets. You are reading this essay due to the superlative efforts of my assistant Ajay who has typed some eighty pages. This essay is dedicated to all Indian saints particularly Veda Vyasa, Sankara, Samartha Ramdas, Namdev, Mirabai, Guru Govind Singh, Swami Dayananda Saraswati, Narayan Guru, Sri Aurobindo, Sri Ramana Maharshi and all Bharityas who have sacrificed their lives for the protection of Bharat. Before you go ahead I must say that no civilization, culture can survive if its people adopt the path of non-violence read to mean not retaliating even when you are attacked. Quoting Swami Sivananda “Who is a saint? He who lives in God or the Eternal, who is free from egoism, likes and dislikes, selfishness, vanity, mine-ness, lust, greed and anger, who is endowed with equal vision, balanced mind, mercy, tolerance, righteousness and cosmic love, and who has divine knowledge is a saint. Saints and sages only can become real advisors to the kings, because they are selfless and possess the highest wisdom. -

The Ur-Mahabharata

Approaches to the Ur-Mahabharata Zdenko Zlatar 1 The· problem of the Vr-Mahabharata There is a sloka in The Mahabharata which can be translated like this: 'Whatever is found here can be found elsewhere; what is not found here cannot be found anywhere else'. 1 This illustrates very well the variety of approaches to, and interpretations of, the epic for over a hundred and fifty years. Yet, when all of them are taken into account, it can be seen that they fall into a combination of one or two of four categories: 1) The Mahabharata as a unitary epic; 2) The Mahabharata as a composite epic; 3) The Mahabharata as a symbolic representation; 4) The Mahabharata as a real event. Of course, it is possible to combine (1) or (2) with (3) or (4), but it is not possible to hold (1) and (2) at the same time. Holding both (3) and (4) together is possible, but has not so far been put forward. In the nineteenth century Max Muller stated that all the gods of the Rig Veda were aspects of the sun. If, as Mary Carroll Smith argues, the key to The Mahabharata lies in the Rig Veda, then this proposition must be looked at. It was Adolf Holtzmann, Sr, who first intimated it, and his nephew, Adolf Holtzmann, Jr, who argued in 1895 that The Mahabharata contained various layers and reworkings, and that the present version is both an expanded and a re-worked epic (an 'analytic' approach). This thesis was rejected by Joseph Dahlmann who in the same year 1895 defended The Mahabharata as a unitary epic (a 'synthetic' approach). -

Did Lord Krishna Exist?

Raj Nambisan: Did Lord Krishna exist? Most certainly, says Dr Manish Pandit, a nuclear medicine physician who teaches in the United Kingdom , proffering astronomical, archaeological, linguistic and oral evidences to make his case. "I used to think of Krishna is a part of Hindu myth and mythology. Imagine my surprise when I came across Dr Narhari Achar (a professor of physics at the University of Memphis, Tennessee, in the US ) and his research in 2004 and 2005. He had done the dating of the Mahabharata war using astronomy. I immediately tried to corroborate all his research using the regular Planetarium software and I came to the same conclusions [as him]," Pandit says. Which meant, he says, that what is taught in schools about Indian history is not correct? The Great War between the Pandavas and the Kauravas took place in 3067 BC, the Pune-born Pandit, who did his MBBS from BJ Medical College there, says in his first documentary, Krishna: History or Myth?. Pandit's calculations say Krishna was born in 3112 BC, so must have been 54-55 years old at the time of the battle of Kurukshetra. Pandit is also a distinguished astrologer, having written several books on the subject.Pandit, as the sutradhar of the documentary Krishna: History or Myth?, uses four pillars -- archaeology, linguistics, what he calls the living tradition of India and astronomy to arrive at the circumstantial verdict that Krishna was indeed a living being, because Mahabharata and the battle of Kurukshetra indeed happened, and since Krishna was the pivot of the Armageddon, it is all true. -

Pan Indian Presence of RISHI MARKANDEY --- Glimpses Into His Life, Victory Over Death, Sites Associated with Him, and Tips for Longevity and Well Being Dr

Scholars Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: Sch J Arts Humanit Soc Sci ISSN 2347-9493 (Print) | ISSN 2347-5374 (Online) Journal homepage: https://saspublishers.com Pan Indian Presence of RISHI MARKANDEY --- Glimpses into his Life, Victory over Death, Sites Associated with him, and Tips for Longevity and well being Dr. Sharadendu Bali1* 1Professor General Surgery, MMIMSR, Mullana, Ambala, Haryana, India DOI: 10.36347/sjahss.2021.v09i05.004 | Received: 07.04.2020 | Accepted: 11.05.2021 | Published: 15.05.2021 *Corresponding author: Dr. Sharadendu Bali Abstract Review Article The concept of One Nation in the vastly diverse population that inhabits the Indian sub-continent, is unique among world civilizations. This feeling of nationalism is as old as the Vedas, and was inculcated and nurtured by some ancient seers and saints. Foremost among them is Rishi Markandeya, whose imprint is not just found all over the Indian landmass, but also traverses all the way to Indonesia and Bali. Markandey is also unique among seers because he is venerated among all the mainstream Indian religious traditions, namely Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Devi cults and ascetic orders. From his birth in the Himalayas, to his severe penance in the dense jungles of the Western Ghats of peninsular India, to the ashrams along the Narmada and Ganges, and going upto the Eastern coast at Jagannath Puri, the Indian sub-continent is strewn with sites named after the great Rishi. The present paper attempts to list out some of these sites, and the accompanying geographical features, in an effort to highlight the immense accomplishments of the Rishi, encompassing fields as diverse as geology, hydrology, philosophy, herbal medicine, music, sacred chanting, goddess worship, astrology and horticulture.