The Shift in Discourses of Identity in the Eu-Turkey Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast

Briefing May 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 6 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 5 seats 1 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener Karin Feldinger 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Petra Steger Monika Vana* Stefan Windberger 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath Roman Haider Thomas Waitz* Stefan Zotti 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide Vesna Schuster Olga Voglauer Nini Tsiklauri 6. Wolfram Pirchner Julia Elisabeth Herr Elisabeth Dieringer-Granza Thomas Schobesberger Johannes Margreiter 7. Christian Sagartz Christian Alexander Dax Josef Graf Teresa Reiter 8. Barbara Thaler Stefanie Mösl Maximilian Kurz Isak Schneider 9. Christian Zoll Luca Peter Marco Kaiser Andrea Kerbleder Peter Berry 10. Claudia Wolf-Schöffmann Theresa Muigg Karin Berger Julia Reichenhauser NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. Likely to be elected Unlikely to be elected or *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. and/or take seat to take seat, if elected European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Paul Magnette 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 2. Maria Arena* 2. -

Summary Report on AERAP Events on 18 and 19 June

10/07/2013 Working Breakfast of the European Parliament’s AERAP Group (18 June 2013) and 1st Workshop on the Implementation of the AERAP Framework Programme for Cooperation (18/19 June 2013) Summary Report Several Members of the European Parliament, during a working breakfast on 18 June, expressed their support for the objectives of the AERAP Framework Programme for Cooperation. Host of the event, Irish MEP Emer Costello, declared, "This is a very exciting project with enormous potential and it is important that Europe and the EU are at the heart of all this. This is a significant step towards developing closer EU-Africa relations." Italian MEP Vittorio Prodi expressed his excitement about the innovation potential of radio astronomy and the potential for synergies with other science and technology application areas such as satellite navigation. Emer Costello MEP and Spanish MEP Miguel Angel Martinez Martinez were awarded certificates of appreciation in recognition of their on-going engagement for AERAP. Martinez Martinez was a sponsor of the Written Declaration 45/2011 on science capacity building in Africa which led to the establishment of AERAP. Other MEPs present at the workshop included Antonio Fernando Correia de Campos (Portugal), Michael Gahler (Germany), Jan Mulder (Netherlands), Wim van de Camp (Netherlands) and Auke Zijlstra (Netherlands). During the 1st Workshop on the Implementation of the AERAP Framework Programme for Cooperation (18 and 19 June), the participants reviewed the key actions (cooperation initiatives) proposed for each thematic priority of the framework programme in order to evaluate how mature for implementation the actions are. The workshop also undertook an initial survey of potential participants in these actions. -

List of LIBE-Members

Sheet1 Heinz K. BECKER Member Austria epp Harald VILIMSKY Member Austria enf @vilimsky Josef WEIDENHOLZER Member Austria sd @Weidenholzer Ulrike LUNACEK Substitute Austria greensefa @UlrikeLunacek Angelika MLINAR Substitute Austria aldeadle @AngelikaMlinar Louis MICHEL Member Belgium aldeadle @LouisMichel Helga STEVENS Member Belgium ecr @StevensHelga Gérard DEPREZ Substitute Belgium aldeadle @gerardeprez Sander LOONES Substitute Belgium ecr @SanderLoones Sergei STANISHEV Vice-Chair Bulgaria sd @SergeiStanishev Asim Ahmedov ADEMOV Member Bulgaria epp Filiz HYUSMENOVA Member Bulgaria aldeadle Emil RADEV Substitute Bulgaria epp @Emil_Radev Tomáš ZDECHOVSKÝ Member Czech Republic epp @TomZdechovsky Petr JEŽEK Substitute Czech Republic aldeadle @JezekCZ Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Substitute Czech Republic epp @StetinaEP Morten Helveg PETERSEN Substitute Denmark aldeadle @mortenhelveg Anders Primdahl VISTISEN Substitute Denmark ecr @AndersVistisen Marju LAURISTIN Member Estonia sd @LauristinMarju Jussi HALLA-AHO Member Finland ecr @Halla_aho Petri SARVAMAA Substitute Finland epp @petrisarvamaa Rachida DATI Member France epp @datirachida Nathalie GRIESBECK Member France aldeadle Sylvie GUILLAUME Member France sd @sylvieguillaume Brice HORTEFEUX Member France epp @BriceHortefeux Eva JOLY Member France greensefa @EvaJoly Marie-Christine VERGIAT Member France guengl @MCVergiat Nicolas BAY Substitute France enf @nicolasbayfn Joëlle BERGERON Substitute France efd Gilles LEBRETON Substitute France enf @Gilles_Lebreton Nadine MORANO Substitute France epp @nadine__morano -

De 26 Nederlanders in Het Europees Parlement 2

De 26 Nederlanders in het Europees Parlement 2 Verklaring symbolen Telefoonnummer Brussel Telefoonnummers in Nederland en andere lidstaten GSM GSM Brussel Informatie in deze brochure is bijgewerkt tot februari 2013 DE 26 NEDERLANDERS IN HET EUROPEES PARLEMENT 3 Inhoudsopgave Biografieën 4 Contactgegevens Europarlementariërs 17 Voorlichters 21 Parlementaire commissies 23 Hoe werkt het Europees Parlement? 25 Zetelverdeling 26 Bezoeken 27 Adressen 28 Vergaderdata 29 DE 26 NEDERLANDERS IN HET EUROPEES PARLEMENT 4 In dit boekje vindt u de namen en contactgegevens van de 26 Nederlandse leden van het Europees Parlement. De Europarlementariërs van het CDA maken deel uit CDA van de fractie van de Europese Volkspartij (Christen- Democraten) (EVP) Wim van de Camp (delegatieleider) Geboren 27-07-1953 te Oss. Hogere Landbouwschool voor Tropische Landbouw en studie Rechten aan de Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen. Juridisch beleidsmedewerker bij de VNG (1982-1986). Lid van de Tweede Kamer (1986 -2009). Lid van het EP sinds 2009. Lid van de Commissie burgerlijke vrijheden, justitie en binnenlandse zaken. Plv. lid van de Commissie interne markt en consumentenbescherming. Plv. lid van de Bijzondere Commissie georganiseerde misdaad, corruptie en witwassen. Plv. lid van de Subcommissie mensenrechten. Lid van de delegatie voor de betrekkingen met de Volksrepubliek China. Plv. lid van de delegatie voor de betrekkingen met Albanië, Bosnië-Herzegovina, Servië, Montenegro en Kosovo. Esther de Lange Geboren 19-02-1975 te Spaubeek. Studie Hogere Europese Beroepsopleiding en Internationale Betrekkingen. Projectmedewerker FEANTSA (Europese federatie van dak- en thuislozenorganisaties) (1997). Medewerker Europese zaken twee Duitse brancheverenigingen (1998-1999). Beleidsmedewerker Europarlementariër (1999-2007). Voorzitter werkveldcommissie Hogere Europese Beroepen Opleiding, Hogeschool Zuyd, Maastricht (sinds 2003). -

Language, Values and Populist Frames

Paradise lost: Language, values and populist frames September 21, 2017 Metropolis Symposium, The Hague CULTURAL INTELLIGENCE FOR DECISION MAKERS 1 | Counterpoint on Framing Ulrike Grassinger is a social-psychologist by background who brings together insights on human behaviour, sentiment and choice with her experience in managing large-scale consultancy projects for business and political leaders. She regularly facilitates high-level workshops to advise decision-makers on how to make use of these insights. Before joining Counterpoint, Ulrike worked as a management consultant where she advised senior-level management and led large-scale change projects. Trained as a systemic consultant and therapist, she has experience in working with systems, organisations and groups to foster shifts in perspectives. 2 | Counterpoint on Framing Kick Burden Relief Hammer 3 | Counterpoint on Framing BurdenTaxes TaxesRelief 4 | Counterpoint on Framing 98 % of our thoughts are associative and automatic. It takes a lot to overcome this. System 1 System 2 Fast Slow Automatic Considered Associative Deliberative Emotional Logical Engage Encourage Daniel Kahneman, ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ 5 | Counterpoint on Framing We see the world differently. 6 | Counterpoint on Framing 6 7 | Counterpoint on Framing Are they hotdogs or legs? 8 | Counterpoint on Framing We all have mental frames. We use them to filter information and arguments. 9 | Counterpoint on Framing Communication frames trigger certain mental frames. Hotdog frame 10 | Counterpoint on Framing Mental frames consist of visible attitudes and often invisible values. Attitudes Values 11 | Counterpoint on Framing Mental frames consist of visible attitudes and often invisible values. “Migrants are “We should be proud taking our job” of taking in migrants” “We are too small a “Migration is good country to take any for our country” more migrants” Values 12 | Counterpoint on Framing Mental frames consist of visible attitudes and often invisible values. -

Official Directory of the European Union

ISSN 1831-6271 Regularly updated electronic version FY-WW-12-001-EN-C in 23 languages whoiswho.europa.eu EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN UNION Online services offered by the Publications Office eur-lex.europa.eu • EU law bookshop.europa.eu • EU publications OFFICIAL DIRECTORY ted.europa.eu • Public procurement 2012 cordis.europa.eu • Research and development EN OF THE EUROPEAN UNION BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑ∆Α • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND -

European Parliament

27.10.2016 EN Off icial Jour nal of the European Union C 397/1 Wednesday 16 September 2015 IV (Notices) NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2015-2016 SESSION Sittings of 16 to 17 September 2015 BRUSSELS MINUTES OF THE SITTING OF 16 SEPTEMBER 2015 (2016/C 397/01) Contents Page 1. Resumption of the session . 7 2. Approval of the minutes of the previous sitting . 7 3. Verification of credentials . 7 4. Request for the waiver of parliamentary immunity . 7 5. Action taken following a request for waiver of immunity . 7 6. Composition of committees and delegations . 8 7. Decisions concerning certain documents . 8 8. Documents received . 8 9. Order of business . 9 10. Conclusions of the Justice and Home Affairs Council on migration (14 September 2015) (debate) . 10 C 397/2 EN Off icial Jour nal of the European Union 27.10.2016 Wednesday 16 September 2015 Contents Page 11. UN Sustainable Development summit (25-27 September 2015) and development-related aspects of the 11 COP 21 (debate) . 12. Composition of committees . 12 13. Voting time . 12 13.1. Preparation of the Commission Work Programme 2016 (vote) . 12 14. Corrections to votes and voting intentions . 12 15. Decision adopted on 15 July 2015 on the energy summer package (debate) . 13 16. Ongoing crisis in the agriculture sector (debate) . 13 17. One-minute speeches on matters of political importance . 14 18. Explanations of vote . 14 19. Agenda of the next sitting . 14 20. Closure of the sitting . 14 ATTENDANCE REGISTER . 15 ANNEX I RESULT OF VOTES . -

Energy Policy Dynamics in the European Parliament and in the Lithuanian Seimas

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 Energy Policy Dynamics in the European Parliament and in the Lithuanian Seimas Vaida Lilionyte Manthos West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Manthos, Vaida Lilionyte, "Energy Policy Dynamics in the European Parliament and in the Lithuanian Seimas" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8290. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8290 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Energy Policy Dynamics in the European Parliament and in the Lithuanian Seimas Vaida Lilionyte Manthos Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Science at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science John Kilwein, Ph.D., Chair Shauna Fisher, Ph.D. Erik S. Herron, Ph.D. Daniel Renfrew, Ph.D. -

Ranking European Parliamentarians on Climate Action

Ranking European Parliamentarians on Climate Action EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CONTENTS With the European elections approaching, CAN The scores were based on the votes of all MEPs on Austria 2 Europe wanted to provide people with some these ten issues. For each vote, MEPs were either Belgium 3 background information on how Members of the given a point for voting positively (i.e. either ‘for’ Bulgaria 4 European Parliament (MEPs) and political parties or ‘against’, depending on if the text furthered or Cyprus 5 represented in the European Parliament – both hindered the development of climate and energy Czech Republic 6 national and Europe-wide – have supported or re- policies) or no points for any of the other voting Denmark 7 jected climate and energy policy development in behaviours (i.e. ‘against’, ‘abstain’, ‘absent’, ‘didn’t Estonia 8 the last five years. With this information in hand, vote’). Overall scores were assigned to each MEP Finland 9 European citizens now have the opportunity to act by averaging out their points. The same was done France 10 on their desire for increased climate action in the for the European Parliament’s political groups and Germany 12 upcoming election by voting for MEPs who sup- all national political parties represented at the Greece 14 ported stronger climate policies and are running European Parliament, based on the points of their Hungary 15 for re-election or by casting their votes for the respective MEPs. Finally, scores were grouped into Ireland 16 most supportive parties. CAN Europe’s European four bands that we named for ease of use: very Italy 17 Parliament scorecards provide a ranking of both good (75-100%), good (50-74%), bad (25-49%) Latvia 19 political parties and individual MEPs based on ten and very bad (0-24%). -

Liste Des Membres

Commission des affaires économiques et monétaires Membres Sharon BOWLES Présidente Groupe Alliance des démocrates et des libéraux pour l'Europe Royaume-Uni Liberal Democrats Party Pablo ZALBA BIDEGAIN Vice-président Groupe du Parti Populaire Européen (Démocrates-Chrétiens) Espagne Partido Popular Arlene McCARTHY Vice-présidente Groupe de l'Alliance Progressiste des Socialistes et Démocrates au Parlement européen Royaume-Uni Labour Party Theodor Dumitru STOLOJAN Vice-président Groupe du Parti Populaire Européen (Démocrates-Chrétiens) Roumanie Partidul Democrat-Liberal Marlene MIZZI Vice-présidente Groupe de l'Alliance Progressiste des Socialistes et Démocrates au Parlement européen Malte Partit Laburista Marino BALDINI Membre Groupe de l'Alliance Progressiste des Socialistes et Démocrates au Parlement européen Croatie Socijaldemokratska partija Hrvatske Burkhard BALZ Membre Groupe du Parti Populaire Européen (Démocrates-Chrétiens) Allemagne Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Elena BĂSESCU Membre Groupe du Parti Populaire Européen (Démocrates-Chrétiens) Roumanie Partidul Democrat-Liberal Jean-Paul BESSET Membre Groupe des Verts/Alliance libre européenne France Europe Écologie Slavi BINEV Membre Groupe Europe libertés démocratie Bulgarie National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria 29/09/2021 1 Godfrey BLOOM Membre Non-inscrits Royaume-Uni United Kingdom Independence Party Udo BULLMANN Membre Groupe de l'Alliance Progressiste des Socialistes et Démocrates au Parlement européen Allemagne Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands Nikolaos -

Minutes of the Sitting of 26 September 2011

27.1.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 22 E/1 Monday 26 September 2011 IV (Notices) NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2011-2012 SESSION Sittings of 26 to 29 September 2011 STRASBOURG MINUTES OF THE SITTING OF 26 SEPTEMBER 2011 (2012/C 22 E/01) Contents Page 1. Resumption of the session . 2 2. Approval of the minutes of the previous sitting . 2 3. Composition of committees and delegations . 3 4. Composition of Parliament . 3 5. Signature of acts adopted under the ordinary legislative procedure . 3 6. Corrigendum (Rule 216) . 4 7. Statements by the President . 4 8. Lapsed written declarations . 4 9. Oral questions and written declarations (submission) . 4 10. Texts of agreements forwarded by the Council . 5 11. Action taken on Parliament's resolutions . 5 12. Petitions . 5 13. Transfers of appropriations . 6 C 22 E/2 EN Official Journal of the European Union 27.1.2012 Monday 26 September 2011 Contents (continued) Page 14. Documents received . 7 15. Order of business . 9 16. EU research and innovation funding (debate) . 9 17. Trade in agricultural and fishery products between the EU and Palestine *** (debate) . 10 18. EU-Taiwan trade (debate) . 10 19. Tourism in Europe (debate) . 11 20. One-minute speeches on matters of political importance . 12 21. European road safety (short presentation) . 12 22. Dam infrastructure in developing countries (short presentation) . 12 23. Assisting developing countries in addressing food security challenges (short presentation) 13 24. European Schools system (short presentation) . 13 25. Future EU cohesion policy (short presentation) . -

List of Members

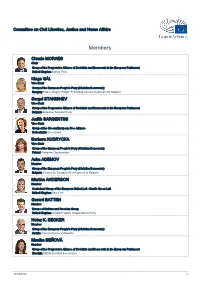

Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Members Claude MORAES Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Kinga GÁL Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Hungary Fidesz-Magyar Polgári Szövetség-Kereszténydemokrata Néppárt Sergei STANISHEV Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Bulgaria Bulgarian Socialist Party Judith SARGENTINI Vice-Chair Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Netherlands GroenLinks Barbara KUDRYCKA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska Asim ADEMOV Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Bulgaria Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria Martina ANDERSON Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left United Kingdom Sinn Fein Gerard BATTEN Member Europe of Nations and Freedom Group United Kingdom United Kingdom Independence Party Heinz K. BECKER Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Austria Österreichische Volkspartei Monika BEŇOVÁ Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Slovakia SMER-Sociálna demokracia 27/09/2021 1 Malin BJÖRK Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Sweden Vänsterpartiet Michał BONI Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska Caterina