Energy Policy Dynamics in the European Parliament and in the Lithuanian Seimas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synopsis of the Meeting Held in Strasbourg on 21 January 2013

BUREAU OF THE ASSEMBLY AS/Bur/CB (2013) 01 21 January 2013 TO THE MEMBERS OF THE ASSEMBLY Synopsis of the meeting held in Strasbourg on 21 January 2013 The Bureau of the Assembly, meeting on 21 January 2013 in Strasbourg, with Mr Jean-Claude Mignon, President of the Assembly, in the Chair, as regards: - First part-session of 2013 (Strasbourg, 21-25 January 2013): i. Requests for debates under urgent procedure and current affairs debates: . decided to propose to the Assembly to hold a debate under urgent procedure on “Migration and asylum: mounting tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean” on Thursday 24 January 2013 and to refer this item to the Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced Persons for report; . decided to propose to the Assembly to hold the debate under urgent procedure on “Recent developments in Mali and Algeria and the threat to security and human rights in the Mediterranean region” on Thursday 24 January 2013 and to refer this item to the Committee on Political Affairs and Democracy for report; . decided not to hold a current affairs debate on “The deteriorating situation in Georgia”; . took note of the decision by the UEL Group to withdraw its request for a current affairs debate on “Political developments in Turkey regarding the human rights of the Kurds and other minorities”; ii. Draft agenda: updated the draft agenda; - Progress report of the Bureau of the Assembly and of the Standing Committee (5 October 2012 – 21 January 2013): (Rapporteur: Mr Kox, Netherlands, UEL): approved the Progress report; - Election observation: i. Presidential election in Armenia (18 February 2013): took note of the press release issued by the pre-electoral mission (Yerevan, 15-18 January 2013) and approved the final composition of the ad hoc committee to observe these elections (Appendix 1); ii. -

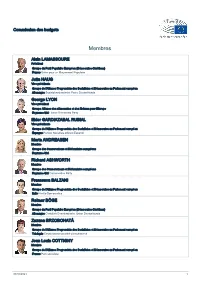

Liste Des Membres

Commission des budgets Membres Alain LAMASSOURE Président Groupe du Parti Populaire Européen (Démocrates-Chrétiens) France Union pour un Mouvement Populaire Jutta HAUG Vice-présidente Groupe de l'Alliance Progressiste des Socialistes et Démocrates au Parlement européen Allemagne Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands George LYON Vice-président Groupe Alliance des démocrates et des libéraux pour l'Europe Royaume-Uni Liberal Democrats Party Eider GARDIAZABAL RUBIAL Vice-présidente Groupe de l'Alliance Progressiste des Socialistes et Démocrates au Parlement européen Espagne Partido Socialista Obrero Español Marta ANDREASEN Membre Groupe des Conservateurs et Réformistes européens Royaume-Uni - Richard ASHWORTH Membre Groupe des Conservateurs et Réformistes européens Royaume-Uni Conservative Party Francesca BALZANI Membre Groupe de l'Alliance Progressiste des Socialistes et Démocrates au Parlement européen Italie Partito Democratico Reimer BÖGE Membre Groupe du Parti Populaire Européen (Démocrates-Chrétiens) Allemagne Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Zuzana BRZOBOHATÁ Membre Groupe de l'Alliance Progressiste des Socialistes et Démocrates au Parlement européen Tchéquie Česká strana sociálně demokratická Jean Louis COTTIGNY Membre Groupe de l'Alliance Progressiste des Socialistes et Démocrates au Parlement européen France Parti socialiste 01/10/2021 1 Isabelle DURANT Membre Groupe des Verts/Alliance libre européenne Belgique Ecologistes Confédérés pour l'Organisation de Luttes Originales James ELLES Membre Groupe des Conservateurs -

17. One-Minute Speeches on Matters of Political Importance 18. Passenger Car Related Taxes

C 305 E/14 Official Journal of the European Union EN 14.12.2006 Monday 4 September 2006 Thursday — Debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law (Rule 115): — Request from the PSE Group to replace the item on Zimbabwe (Item 56 on the final draft agenda) with an item on Transnistria. The following spoke: Hannes Swoboda, on behalf of the PSE Group, who moved the request, Marianne Mikko and Charles Tannock. Parliament rejected the request by electronic vote (74 in favour, 103 against, 19 abstentions). The order of business was thus established. 17. One-minute speeches on matters of political importance Pursuant to Rule 144, the following Members who wished to draw the attention of Parliament to matters of political importance spoke for one minute: Geoffrey Van Orden, Marc Tarabella, Danutė Budreikaitė, Margrete Auken, Pedro Guerreiro, Janusz Wojcie- chowski, Thomas Wise, Georgios Karatzaferis, Ashley Mote, James Nicholson, Justas Vincas Paleckis, Lívia Járóka, Pál Schmitt, Bogusław Liberadzki, Antolín Sánchez Presedo, Kyriacos Triantaphyllides, Véronique De Keyser, Glenys Kinnock, Romana Jordan Cizelj, Ioannis Gklavakis, Sophia in 't Veld, Monika Beňová, Vytau- tas Landsbergis, Georgios Papastamkos, Csaba Sándor Tabajdi, Árpád Duka-Zólyomi, Adamos Adamou, Mai- read McGuinness, Marianne Mikko, Richard Corbett, Manuel Medina Ortega, Marios Matsakis, Simon Busut- til, Milan Gaľa, Marie Panayotopoulos-Cassiotou and Inés Ayala Sender. IN THE CHAIR: Sylvia-Yvonne KAUFMANN Vice-President 18. Passenger car related taxes * (debate) Report on the proposal for a Council directive on passenger car related taxes [COM(2005)0261 — C6-0272/2005 — 2005/0130(CNS)] — Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs. -

2010. Június 23-I Ülés Jegyzőkönyve

2010.9.24. HU Az Európai Unió Hivatalos Lapja C 257 E/303 2010. június 23., szerda ÜLÉSSZAK: 2010 - 2011 2010. június 23-i ülés BRÜSSZEL 2010. JÚNIUS 23-I ÜLÉS JEGYZŐKÖNYVE (2010/C 257 E/05) Tartalom Oldal 1. Az ülésszak folytatása . 303 2. Az előző ülés jegyzőkönyvének elfogadása . 304 3. Az elnök nyilatkozatai . 304 4. Köszöntés . 304 5. A képviselőcsoportok tagjai . 304 6. A Parlament tagjai . 304 7. A bizottságok és a küldöttségek tagjai . 304 8. Egy európai gyorsriasztási rendszer létrehozása a pedofilok és a szexuális zaklatók ellen (írás beli nyilatkozat) . 305 9. A 2010. június 17-i Európai Tanács következtetései (vita) . 305 10. Dokumentumok benyújtása . 305 11. A következő ülések időpontjai . 306 12. Az ülésszak megszakítása . 306 JELENLÉTI ÍV . 307 1. MELLÉKLET – Egy európai gyorsriasztási rendszer létrehozása a pedofilok és a szexuális zaklatók ellen (írásbeli nyilatkozat) . 308 2010. JÚNIUS 23-I ÜLÉS JEGYZŐKÖNYVE ELNÖKÖL: Jerzy BUZEK elnök 1. Az ülésszak folytatása Az ülést 15.05-kor nyitják meg. C 257 E/304 HU Az Európai Unió Hivatalos Lapja 2010.9.24. 2010. június 23., szerda 2. Az előző ülés jegyzőkönyvének elfogadása Az előző ülés jegyzőkönyvét elfogadják. 3. Az elnök nyilatkozatai Az elnök nyilatkozatot tesz 2010. június 21–22-i hivatalos oroszországi látogatása alkalmából; az Európai Parlament elnöke 12 éve nem látogatott Oroszországba. 4. Köszöntés Az elnök a Parlament nevében köszönti az indonéz parlament Kemal Azis Stamboel küldöttségi elnök vezette küldöttségét, melynek tagjai a hivatalos galérián foglaltak helyet. 5. A képviselőcsoportok tagjai Mike Nattrass közli az Elnökséggel, hogy kilépett az EFD képviselőcsoportból és a mai naptól, azaz 2010. -

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast

Briefing May 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 6 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 5 seats 1 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener Karin Feldinger 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Petra Steger Monika Vana* Stefan Windberger 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath Roman Haider Thomas Waitz* Stefan Zotti 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide Vesna Schuster Olga Voglauer Nini Tsiklauri 6. Wolfram Pirchner Julia Elisabeth Herr Elisabeth Dieringer-Granza Thomas Schobesberger Johannes Margreiter 7. Christian Sagartz Christian Alexander Dax Josef Graf Teresa Reiter 8. Barbara Thaler Stefanie Mösl Maximilian Kurz Isak Schneider 9. Christian Zoll Luca Peter Marco Kaiser Andrea Kerbleder Peter Berry 10. Claudia Wolf-Schöffmann Theresa Muigg Karin Berger Julia Reichenhauser NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. Likely to be elected Unlikely to be elected or *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. and/or take seat to take seat, if elected European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Paul Magnette 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 2. Maria Arena* 2. -

News from Ukraine

March, 2013 NEWS FROM UKRAINE Rada to adopt EU-recommended bills on data protection, combating discrimination, says speaker The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine will approve the draft laws on amendments to the laws on personal data protection and countering discrimination that was recommended by the European Union, Verkhovna Rada Chairman Volodymyr Rybak has said. “There are several key issues that need to be addressed as soon as possible. In particular, these are the legal regulation of the fight against corruption, and the introduction of the EU-recommended amendments to Ukraine’s laws in the field of personal data protection and combating discrimination,” Mr. Rybak stated at a meeting of the Interparliamentary Assembly of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, the Seimas of Lithuania, the Sejm and Senate of Poland in Warsaw on 26 March. Mr. Rybak said the Verkhovna Rada has already adopted most of the laws that are needed to implement the first stage of the action plan on the liberalization of the EU visa regime with Ukraine. In particular, the Parliament passed the laws dealing with the issues related to migration, a resolution to introduce biometric travel documents. Besides, a system of personal data protection was created in Ukraine. According to the Ukrainian Parliament’s Chair, Ukraine plans to submit to the European side soon its third report on the implementation of the first stage of the visa liberalization action plan, which would give the EU grounds to switch to the second stage. Read more: Interfax Ukraine, 26 March 2013 http://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/146376.html#.UVGP7DesZVQ Ukrainian Parliament ratifies visa facilitation agreement with EU Some 275 of the 350 MPs registered in the parliamentary sitting hall supported the Law “On the Ratification of the Amended Visa Facilitation Agreement between Ukraine and the EU”. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta the Law Courts A1 Sir Winston Churchill Square Edmonton Alberta T5J-0R2

Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta Citation: AVI v MHVB, 2020 ABQB 489 Date: 20200826 Docket: FL03 55142 Registry: Edmonton Between: AVI Applicant and MHVB Respondent and Jacqueline Robinson, a.k.a. Jacquie Phoenix Third Party and Unauthorized Alleged Representative _______________________________________________________ Memorandum of Decision of the Honourable Mr. Justice Robert A. Graesser _______________________________________________________ I. Introduction [1] Pseudolaw is a collection of spurious legally incorrect ideas that superficially sound like law, and purport to be real law. In layman’s terms, pseudolaw is pure nonsense. [2] Pseudolaw is typically employed by conspiratorial, fringe, criminal, and dissident minorities who claim pseudolaw replaces or displaces conventional law. These groups attempt to Page: 2 gain advantage, authority, and other benefits via this false law. In Meads v Meads, 2012 ABQB 571 [Meads], Associate Chief Justice Rooke reviewed many forms of and variations on pseudolaw that have been deployed in Canada. In his decision, he described populations and personalities that use these ideas, and explained how these “Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Argument” [“OPCA”] concepts are legally false and universally rejected by Canadian courts. Rooke ACJ concluded OPCA strategies are instead scams promoted to gullible, ill-informed, and often greedy individuals by unscrupulous “guru” personalities. Employing pseudolaw is always an abuse of court processes, and warrants immediate court response: Unrau v National Dental Examining Board, 2019 ABQB 283 at paras 180, 670-671 [Unrau #2]. [3] To date Canada has weathered two waves of pseudolaw. In the 2000 “Detaxers” held seminars and taught classes on how to supposedly avoid paying income tax, for example by claiming that ROBERT GRAESSER is a legal person and a taxpayer, while Robert-A.: Graesser is a physical human being and therefore exempt from tax: Meads at paras 87-98. -

Ireland the Future of Europe Synopsis Nuala Ahern

Labour was usually in Government in coalition with Fine The Future of EuropeEurope:: Perspectives Gael. from Ireland Ireland has been independent from the United Kingdom since 1922 and a Republic since 1949. Ireland was in a currency union with the UK until 1979. For a period of 30 years from 1969 until 1998 there was instability in Is there room for a European Northern Ireland which successive Irish Governments dream in a country captivated in worked to resolve and contain. EU entry in 1972 was the structures of IMF -EU backed by both centre right parties and opposed by adjustment programmes? Is more Labour, which however soon became converted to the European integration desired and European project. Sinn Fein and the small socialist feasible at all? parties are anti - Globalisation and anti EU. The Irish Greens formerly had an influential Eurosceptic wing which is decreasing and many young greens are pro EU. These were among the key questions addressed Most Unions and business organisations are Pro EU. during a seminar on the future of Europe, organised by Green European Foundation with the support of Impact of the financial and economic crisis on the Heinrich Boll Foundation and Green Foundation Ireland Ireland on November 17th in Dublin. This article is a synopsis of the seminar, written by Nuala Ahern, Ireland had a booming economy and massive growth in Chair of the Green Foundation Ireland and former the 1990’s.This turned into a housing bubble, fuelled by Green MEP. low Eurozone interest rates and a global market saturated with liquidity. A comprehensive analysis of how the Irish economy collapsed is contained in the Nyberg Report , an independent report by a Norwegian The seminar took place in Tailors’ Hall, the headquarters economist. -

Brazauskas in Power: an Assessment

Brazauskas in Power: An Assessment * JULIUS SMULKSTYS The victory of Lithuania's Democratic Labor Party (LDDP) in the parliamentary elections of October and November 1992 was lamented by many in the West as the return of the former Communists to power in a country that had played a major role in the dismantling of the Soviet Union. If just a few years ago Lithuania had been the trailblazer in the struggle for independence and democracy, now it seemed to be the leader in efforts to reverse the trends that began in 1988. But to those familiar with the recent history of Lithuania, the election results had no such ominous implications. They merely reflected the growing sophistication of the voters and their reliance on democratic institutions to settle political differences and to redirect as well as to reaffirm economic, social and political reforms. It was the case of a young democracy coming into its own. As in other former republics of the Soviet Union, democratization in Lithuania had to overcome numerous obsta- cles—the most visible ones being the absence of democratic political culture, relentless pressure from Moscow and the resultant siege-like atmosphere, and the rapidly deteriorating economic conditions. One of the important forces that helped to preserve fledgling democratic institutions was the Communist Party of Lithuania (Lietuvos Komunistų Partija—LKP) and its successor, Lithuania's Democratic Labor Party. Without their early commitment, the struggle for democracy and indepen- dence in Lithuania would have been much more difficult. The meaning of the 1992 elections, therefore, can only be fully evaluated and understood in the context of the party's role in promoting change, a role that originated six years ago. -

Studia Interkulturowe Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej 2020/13

WW następnymnastępnym numerzenumerze StudiówStudiów InterkulturowychInterkulturowych EuropyEuropy Środkowo-WschodniejŚrodkowo-Wschodniej międzymiędzy innymi:innymi: 13 tudia nterkulturowe Studia Interkulturowe Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej Europy Interkulturowe Studia S I Izabella Malej „Błok i Jung: inflacja ego Wiersze( o Przepięknej Pani)” Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej Marcin Niemojewski „«I nie tylko w powiastkach drzemie ta historia» – Młyn Bałtaragisa Kazysa Boruty z perspektywy antropologii literatury” TOM 13 www.wuw.pl xStudia Inter nr 13.indd 3 25/10/20 18:53 Studia Interkulturowe EuropyEuropy Środkowo-Wschodniej TOMTOM 13 8 logo WUW.inddWarszawa 1 20155/12/2014 12:54:19 PM Rada Naukowa Madina Aleksejewa, Paweł Bukowiec, Jerzy Grzybowski, Magnus Ilmjärv, Eriks Jekabsons, Peter Kaša, Andrej Liuby, Dangiras Mačiulis, Izabella Malej, Juraj Marusiak, Ljudmila Popovic, Wanda K. Roman, Anatol Wialiki Kolegium redakcyjne Iwona Krycka-Michnowska (Redaktor Naczelna), Joanna Getka (Zastępca Redaktor Naczelnej), Joanna Kozłowska (Sekretarz Redakcji), Monika Grącka, Marcin Niemojewski Adres redakcji 02-678 Warszawa, ul. Szturmowa 4, pok. 319, Polska tel.: (+ 48) 22 55 34 219; tel./faks: (+ 48) 22 55 34 229 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Projekt okładki Jakub Rakusa-Suszczewski Ilustracja na okładce: obraz Małgorzaty Koźbiał Nostalgia Redaktor prowadzący Dorota Dziedzic e-mail: [email protected] Redaktor Mateusz Tokarski ISSN 1898-4215 e-ISSN 2544-3143 © tytułu: Studia Interkulturowe Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej by Jan Koźbiał, -

Guide to Equality and the Policies, Institutions and Programmes of the European Union

Guide to Equality and the Policies, Institutions and Programmes of the European Union Guide to Equality and the Policies, Institutions and Programmes of the European Union By Brian Harvey This document was commissioned by the Equality Authority and the views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Equality Authority. Preface The European Union has played a valuable role in stimulating and shaping equality strategies in Ireland over the past three decades.The majority of key equality initiatives in Ireland can trace their origins to European Union directives, European case law or European Union action programmes. This influence continues to the present moment. However, innovation and ambition in our new equality legislation – the Employment Equality Act, 1998 and the Equal Status Act, 2000 – and our related equality institutions have changed this situation to one of mutual influencing. Europe now looks to the Irish experience of implementing a multi- ground equality agenda for learning. This publication provides an introductory briefing on approaches to equality at the level of the European Union – focusing on policy, institutions and funding programmes. It seeks to resource those who are engaging with the challenge to shape European Union policy and programmes in relation to equality. It aims to assist those addressing the impact of European Union policy and programmes on Ireland or to draw benefit from this influence. It is a unique document in bringing an integrated nine-ground equality focus to policy and programmes at European Union level.We are grateful to Brian Harvey for this work in drawing all this material together in this format.We are also grateful to Jenny Bulbulia B.L.